<Back to Index>

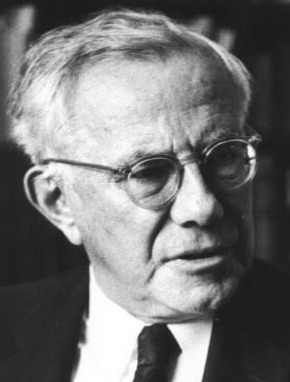

- Theologian and Philosopher Paul Johannes Tillich, 1886

PAGE SPONSOR

Paul Johannes Tillich (August 20, 1886 – October 22, 1965) was a German - American theologian and Christian existentialist philosopher. Tillich was one of the most influential Protestant theologians of the 20th century. Among the general populace, he is best known for his works The Courage to Be (1952) and Dynamics of Faith (1957), which introduced issues of theology and modern culture to a general readership. Theologically, he is best known for his major three volume work Systematic Theology (1951 – 63), in which he developed his "method of correlation": an approach of exploring the symbols of Christian revelation as answers to the problems of human existence raised by contemporary existential philosophical analysis.

Tillich was born on August 20, 1886, in the small village of Starzeddel which was then part of Germany. He was the oldest of three children, with two sisters: Johanna (b. 1888, d. 1920) and Elisabeth (b. 1893). Tillich’s Prussian father Johannes Tillich was a conservative Lutheran pastor of the Evangelical State Church of Prussia's older Provinces; his mother Mathilde Dürselen was from the Rhineland and was more liberal. When Tillich was four, his father became superintendent of a diocese in Schönfliess, a town of three thousand, where Tillich began elementary school. In 1898, Tillich was sent to Königsberg to begin gymnasium. At Königsberg, he lived in a boarding house and experienced loneliness that he sought to overcome by reading the Bible. Simultaneously, however, he was exposed to humanistic ideas at school.

In 1900, Tillich’s father was transferred to Berlin, Tillich switching in 1901 to a Berlin school, from which he graduated in 1904. Before his graduation, however, his mother died of cancer in September 1903, when Tillich was 17. Tillich attended several universities – the University of Berlin beginning in 1904, the University of Tübingen in 1905, and the University of Halle in 1905 - 07. He received his Doctor of Philosophy degree at the University of Breslau in 1911 and his Licentiate of Theology degree at the University of Halle in 1912. During his time at university, he became a member of the Wingolf.

That same year, 1912, Tillich was ordained as a Lutheran minister in the province of Brandenburg. On 28 September 1914 he married Margarethe ("Grethi") Wever (1888 – 1968), and in October he joined the German army as a chaplain. Grethi deserted Tillich in 1919 after an affair that produced a child not fathered by Tillich; the two then divorced. Tillich’s academic career began after the war; he became a Privatdozent of Theology at the University of Berlin, a post he held from 1919 to 1924. On his return from the war he had met Hannah Werner Gottswchow, then married and pregnant. In March 1924 they married; it was the second marriage for both.

During 1924 - 25, he was a Professor of Theology at the University of Marburg, where he began to develop his systematic theology, teaching a course on it during the last of his three terms. From 1925 until 1929, Tillich was a Professor of Theology at the University of Dresden and the University of Leipzig. He held the same post at the University of Frankfurt during 1929 - 33.

While at Frankfurt, Tillich gave public lectures and speeches throughout Germany that brought him into conflict with the Nazi movement. When Hitler became German Chancellor in 1933, Tillich was dismissed from his position. Reinhold Niebuhr visited Germany in the summer of 1933 and, already impressed with Tillich’s writings, contacted Tillich upon learning of Tillich’s dismissal. Niebuhr urged Tillich to join the faculty at New York City’s Union Theological Seminary; Tillich accepted.

At

the age of 47, Tillich moved with his family to America. This meant

learning English, the language in which Tillich would eventually publish

works such as the Systematic Theology.

From 1933 until 1955 he taught at Union, where he began as a Visiting

Professor of Philosophy of Religion. During 1933 - 34 he was also a

Visiting Lecturer in Philosophy at Columbia University.

Tillich acquired tenure at Union in 1937, and in 1940 he was promoted

to Professor of Philosophical Theology and became an American citizen.

At the Union Theological Seminary, Tillich earned his reputation, publishing a series of books that outlined his particular synthesis of Protestant Christian theology and existential philosophy. He published On the Boundary in 1936; The Protestant Era, a collection of his essays, in 1948; and The Shaking of the Foundations, the first of three volumes of his sermons, also in 1948. His collections of sermons would give Tillich a broader audience than he had yet experienced. His most heralded achievements though, were the 1951 publication of volume one of Systematic Theology which brought Tillich academic acclaim, and the 1952 publication of The Courage to Be. The first volume of the systematic theology series prompted an invitation to give the prestigious Gifford lectures during 1953 – 54 at the University of Aberdeen. The latter book, called "his masterpiece" in the Paucks’s biography of Tillich, was based on his 1950 Dwight H. Terry Lectureship and reached a wide general readership.

These works led to an appointment at the Harvard Divinity School in 1955, where he became one of the University’s five University Professors – the five highest ranking professors at Harvard. Tillich’s Harvard career lasted until 1962. During this period he published volume 2 of Systematic Theology and also published the popular book Dynamics of Faith (1957).

In 1962, Tillich moved to the University of Chicago, where he was a Professor of Theology until his death in Chicago in 1965. Volume 3 of Systematic Theology was published in 1963. In 1964 Tillich became the first theologian to be honored in Kegley and Bretall's Library of Living Theology. They wrote: "The adjective ‘great,’ in our opinion, can be applied to very few thinkers of our time, but Tillich, we are far from alone in believing, stands unquestionably amongst these few." A widely quoted critical assessment of his importance was Georgia Harkness' comment, "What Whitehead was to American philosophy, Tillich has been to American theology."

Tillich died on October 22, 1965, ten days after experiencing a heart attack. In 1966 his ashes were interred in the Paul Tillich Park in New Harmony, Indiana.

The key to understanding Tillich’s theology is what he calls the "method of correlation." It is an approach that correlates insights from Christian revelation with the issues raised by existential, psychological and philosophical analysis.

Tillich states in the introduction to the Systematic Theology:

Philosophy formulates the questions implied in human existence, and theology formulates the answers implied in divine self - manifestation under the guidance of the questions implied in human existence. This is a circle which drives man to a point where question and answer are not separated. This point, however, is not a moment in time.

The Christian message provides the answers to the questions implied in human existence. These answers are contained in the revelatory events on which Christianity is based and are taken by systematic theology from the sources, through the medium, under the norm. Their content cannot be derived from questions that would come from an analysis of human existence. They are ‘spoken’ to human existence from beyond it, in a sense. Otherwise, they would not be answers, for the question is human existence itself.

For Tillich, the existential questions of human existence are associated with the field of philosophy and, more specifically, ontology (the study of being). This is because, according to Tillich, a lifelong pursuit of philosophy reveals that the central question of every philosophical inquiry always comes back to the question of being, or what it means to be, to exist, to be a finite human being. To be correlated with these questions are the theological answers, themselves derived from Christian revelation. The task of the philosopher primarily involves developing the questions, whereas the task of the theologian primarily involves developing the answers to these questions. However, it should be remembered that the two tasks overlap and include one another: the theologian must be somewhat of a philosopher and vice versa, for Tillich’s notion of faith as “ultimate concern” necessitates that the theological answer be correlated with, compatible with, and in response to the general ontological question which must be developed independently from the answers. Thus, on one side of the correlation lies an ontological analysis of the human situation, whereas on the other is a presentation of the Christian message as a response to this existential dilemma. For Tillich, no formulation of the question can contradict the theological answer. This is because the Christian message claims, a priori, that the logos “who became flesh” is also the universal logos of the Greeks.

In addition to the intimate relationship between philosophy and theology, another important aspect of the method of correlation is Tillich’s distinction between form and content in the theological answers. While the nature of revelation determines the actual content of the theological answers, the character of the questions determines the form of these answers. This is because, for Tillich, theology must be an answering theology, or apologetic theology. God is called the “ground of being” because God is the answer to the ontological threat of non - being, and this characterization of the theological answer in philosophical terms means that the answer has been conditioned (insofar as its form is considered) by the question. Throughout the Systematic Theology, Tillich is careful to maintain this distinction between form and content without allowing one to be inadvertently conditioned by the other. Many criticisms of Tillich’s methodology revolve around this issue of whether the integrity of the Christian message is really maintained when its form is conditioned by philosophy.

The theological answer is also determined by the sources of theology, our experience, and the norm of theology. Though the form of the theological answers are determined by the character of the question, these answers (which “are contained in the revelatory events on which Christianity is based”) are also “taken by systematic theology from the sources, through the medium, under the norm.” There are three main sources of systematic theology: the Bible, Church history, and the history of religion and culture. Experience is not a source but a medium through which the sources speak. And the norm of theology is that by which both sources and experience are judged with regard to the content of the Christian faith. Thus, we have the following as elements of the method and structure of systematic theology:

- Sources of theology

- Bible

- Church history

- History of religion and culture

- Medium of the sources

- Collective Experience of the Church

- Norm of theology (determines use of sources)

- Content of which is the biblical message itself, for example:

- Justification through faith

- New Being in Jesus as the Christ

- The Protestant Principle

- The criterion of the cross

- Content of which is the biblical message itself, for example:

As McKelway explains, the sources of theology contribute to the formation of the norm, which then becomes the criterion through which the sources and experience are judged. The relationship is circular, as it is the present situation which conditions the norm in the interaction between church and biblical message. The norm is then subject to change, but Tillich insists that its basic content remains the same: that of the biblical message. It is tempting to conflate revelation with the norm, but we must keep in mind that revelation (whether original or dependent) is not an element of the structure of systematic theology per se, but an event. For Tillich, the present day norm is the “New Being in Jesus as the Christ as our Ultimate Concern”. This is because the present question is one of estrangement, and the overcoming of this estrangement is what Tillich calls the “New Being”. But since Christianity answers the question of estrangement with “Jesus as the Christ”, the norm tells us that we find the New Being in Jesus as the Christ.

There

is also the question of the validity of the method of correlation.

Certainly one could reject the method on the grounds that there is no a priori reason

for its adoption. But Tillich claims that the method of any theology

and its system are interdependent. That is, an absolute methodological

approach cannot be adopted because the method is continually being

determined by the system and the objects of theology.

Tillich used the concept of "being" in systematic theology. There are 3 roles :

... [The concept of Being] appears in the present system in three places: in the doctrine of God, where God is called the being as being or the ground and the power of being;

in the doctrine of man, where the distinction is carried through between man's essential and his existential being;

and finally, in the doctrine of the Christ, where he is called the manifestation of the New Being, the actualization of which is the work of the divine Spirit.

— Tillich, Systematic Theology Vol. 2, p.10

...It is the expression of the experience of being over against non - being. Therefore, it can be described as the power of being which resists non - being. For this reason, the medieval philosophers called being the basic transcendentale, beyond the universal and the particular...

The same word, the emptiest of all concepts when taken as an abstraction, becomes the most meaningful of all concepts when it is understood as the power of being in everything that has being.

— Tillich, Systematic Theology Vol. 2, p.11

This is part four of Tillich's Systematic Theology. In this part, Tillich talks about life and the divine Spirit.

Life remains ambiguous as long as there is life. The question implied in the ambiguities of life derives to a new question, namely, that of the direction in which life moves. This is the question of history. Systematically speaking, history, characterized as it as by its direction toward the future, is the dynamic quality of life. Therefore, the "riddle of history" is a part of the problem of life.

— Tillich, Systematic Theology, Vol.2 , p.4

Tillich stated the courage to take meaninglessness into oneself presupposes a relation to the ground of being: absolute faith. Absolute faith can transcend the theistic idea of God, and has three elements.

… The first element is the experience of the power of being which is present even in the face of the most radical manifestation of non being. If one says that in this experience vitality resists despair, one must add that vitality in man is proportional to intentionality. The vitality that can stand the abyss of meaninglessness is aware of a hidden meaning within the destruction of meaning.

— Tillich, The Courage to Be, p.177

The second element in absolute faith is the dependence of the experience of nonbeing on the experience of being and the dependence of the experience of meaninglessness on the experience of meaning. Even in the state of despair one has enough being to make despair possible.

— Tillich, The Courage to Be, p.177

There is a third element in absolute faith, the acceptance of being accepted. Of course, in the state of despair there is nobody and nothing that accepts. But there is the power of acceptance itself which is experienced. Meaninglessness, as long as it is experienced, includes an experience of the "power of acceptance". To accept this power of acceptance consciously is the religious answer of absolute faith, of a faith which has been deprived by doubt of any concrete content, which nevertheless is faith and the source of the most paradoxical manifestation of the courage to be.

— Tillich, The Courage to Be, p.177

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Tillich believes the essence of religious attitudes is what he calls "ultimate concern". Separate from all profane and ordinary realities, the object of the concern is understood as sacred, numinous or holy. The perception of its reality is felt as so overwhelming and valuable that all else seems insignificant, and for this reason requires total surrender. In 1957, Tillich defined his conception of faith more explicitly in his work, Dynamics of Faith.

… "Man, like every living being, is concerned about many things, above all about those which condition his very existence...If [a situation or concern] claims ultimacy it demands the total surrender of him who accepts this claim... it demands that all other concerns... be sacrificed."

— Tillich, Dynamics of Faith, p.1-2

Tillich further refined his conception of faith by stating that

… "Faith as ultimate concern is an act of the total personality. It is the most centered act of the human mind... it participates in the dynamics of personal life."

— Tillich, Dynamics of Faith, p.5

An arguably central component of Tillich's concept of faith is his notion that faith is "ecstatic". That is to say that

… "It transcends both the drives of the nonrational unconsciousness and the structures of the rational conscious... the ecstatic character of faith does not exclude its rational character although it is not identical with it, and it includes nonrational strivings without being identical with them. 'Ecstasy' means 'standing outside of oneself' - without ceasing to be oneself - with all the elements which are united in the personal center."

— Tillich, Dynamics of Faith, p.8-9

In short, for Tillich, faith does not stand opposed to rational or nonrational elements (reason and emotion respectively), as some philosophers would maintain. Rather, it transcends them in an ecstatic passion for the ultimate.

It should also be noted that Tillich does not exclude atheists in

his exposition of faith. Everyone has an ultimate concern, and this

concern can be in an act of faith, "even if the act of faith includes

the denial of God. Where there is ultimate concern, God can be denied

only in the name of God"

Throughout most of his works Paul Tillich provides an apologetic and alternative ontological view of God. Traditional medieval philosophical theology in the work of figures such as St. Anselm, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, and William of Ockham tended to understand God as the highest existing Being, to which predicates such as omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence, goodness, righteousness, holiness, etc. may be ascribed. Arguments for and against the existence of God presuppose such an understanding of God. Tillich is critical of this mode of discourse which he refers to as "theological theism," and argues that if God is a Being [das Seiende], even if the highest Being, God cannot be properly called the source of all being, and the question can of course then be posed as to why God exists, who created God, when God's beginning is, and so on. To put the issue in traditional language: if God is a being [das Seiende], then God is a creature, even if the highest one, and thus cannot be the Creator. Rather, God must be understood as the "ground of Being - Itself." The problem persists in the same way when attempting to determine whether God is an eternal essence, or an existing being, neither of which are adequate, as traditional theology was well aware. When God is understood in this way, it becomes clear that not only is it impossible to argue for the "existence" of God, since God is beyond the distinction between essence and existence, but it is also foolish: one cannot deny that there is being, and thus there is a Power of Being. The question then becomes whether and in what way personal language about God and humanity's relationship to God is appropriate. In distinction to "theological theism," Tillich refers to another kind of theism as that of the "divine - human encounter." Such is the theism of the encounter with the "Holy Other," as in the work of Karl Barth and Rudolf Otto, and implies a personalism with regard to God's self revelation. Tillich is quite clear that this is both appropriate and necessary, as it is the basis of the personalism of Biblical Religion altogether and the concept of the "Word of God", but can become falsified if the theologian tries to turn such encounters with God as the Holy Other into an understanding of God as a being. In other words, God is both personal and transpersonal.

Tillich's ontological view of God is not without precedent in the history of Christian theology. Many theologians, especially in the period denoted by scholars as the Hellenistic or Patristic period of Christian theology, that of the Church Fathers, understood God as the "unoriginate source" (agennetos) of all being. This was the view, in particular, of the theologian Origen, one among the crowd of thinkers by whom Tillich was deeply influenced, and who themselves had shown notable influences from middle Platonism.

Tillich further argues that theological theism is not only logically problematic, but is unable to speak into the situation of radical doubt and despair about meaning in life, which is the primary problem typical of the modern age, as opposed to a fundamental anxiety about fate and death or guilt and condemnation. This is because the state of finitude entails by necessity anxiety, and that it is our finitude as human beings, our being a mixture of being and nonbeing, that is at the ultimate basis of anxiety. If God is not the ground of being itself, then God cannot provide an answer to the question of finitude; God would also be finite in some sense. The term "God Above God," then, means to indicate the God who appears, who is the ground of being itself, when the "God" of theological theism has disappeared in the anxiety of doubt. While on the one hand this God goes beyond the God of theological theism, it is nevertheless rooted in the religious symbols of Christian faith, particularly that of the crucified Christ, and is, according to Tillich, the possibility of the recovery of religious symbols which may otherwise have become ineffective in contemporary society.

Tillich argues that the God of theological theism is at the root of much revolt against theism and religious faith in the modern period. Tillich states, sympathetically, that the God of theological theism

deprives me of my subjectivity because he is all - powerful and all - knowing. I revolt and make him into an object, but the revolt fails and becomes desperate. God appears as the invincible tyrant, the being in contrast with whom all other beings are without freedom and subjectivity. He is equated with the recent tyrants who with the help of terror try to transform everything into a mere object, a thing among things, a cog in a machine they control. He becomes the model of everything against which Existentialism revolted. This is the God Nietzsche said had to be killed because nobody can tolerate being made into a mere object of absolute knowledge and absolute control. This is the deepest root of atheism. It is an atheism which is justified as the reaction against theological theism and its disturbing implications.

Another reason Tillich criticized theological theism was because it placed God into the subject - object dichotomy. This is the basic distinction made in Epistemology, that branch of Philosophy which deals with human knowledge, how it is possible, what it is, and its limits. Epistemologically, God cannot be made into an object, that is, an object of the knowing subject. Tillich deals with this question under the rubric of the relationality of God. The question is "whether there are external relations between God and the creature." Traditionally Christian theology has always understood the doctrine of creation to mean precisely this external relationality between God, the Creator, and the creature as separate and not identical realities. Tillich reminds us of the point, which can be found in Luther, that "there is no place to which man can withdraw from the divine thou, because it includes the ego and is nearer to the ego than the ego to itself." Tillich goes further to say that the desire to draw God into the subject - object dichotomy is an "insult" to the divine holiness. Similarly, if God were made into the subject rather than the object of knowledge (The Ultimate Subject), then the rest of existing entities then become subjected to the absolute knowledge and scrutiny of God, and the human being is "reified," or made into a mere object. It would deprive the person of his or her own subjectivity and creativity. According to Tillich, theological theism has provoked the rebellions found in atheism and Existentialism, although other social factors such as the industrial revolution have also contributed to the "reification" of the human being. The modern man could no longer tolerate the idea of being an "object" completely subjected to the absolute knowledge of God. Tillich argued, as mentioned, that theological theism is "bad theology".

The God of the theological theism is a being besides others and as such a part of the whole reality. He is certainly considered its most important part, but as a part and therefore as subjected to the structure of the whole. He is supposed to be beyond the ontological elements and categories which constitute reality. But every statement subjects him to them. He is seen as a self which has a world, as an ego which relates to a thought, as a cause which is separated from its effect, as having a definite space and endless time. He is a being, not being - itself"

Alternatively, Tillich presents the above mentioned ontological view of God as Being - Itself, Ground of Being, Power of Being, and occasionally as Abyss or God's "Abysmal Being." What makes Tillich's ontological view of God different from theological theism is that it transcends it by being the foundation or ultimate reality that "precedes" all beings. Just as Being for Heidegger is ontologically prior to conception, Tillich views God to be beyond Being - Itself, manifested in the structure of beings. God is not a supernatural entity among other entities. Instead, God is the ground upon which all beings exist. We cannot perceive God as an object which is related to a subject because God precedes the subject - object dichotomy.

Thus Tillich dismisses a literalistic Biblicism. Instead of completely rejecting the notion of personal God, however, Tillich sees it as a symbol that points directly to the Ground of Being. Since the Ground of Being ontologically precedes reason, it cannot be comprehended since comprehension presupposes the subject - object dichotomy. Tillich disagreed with any literal philosophical and religious statements that can be made about God. Such literal statements attempt to define God and lead not only to anthropomorphism but also to a philosophical mistake that Immanuel Kant warned against, that setting limits against the transcendent inevitably leads to contradictions. Any statements about God are simply symbolic, but these symbols are sacred in the sense that they function to participate or point to the Ground of Being. Tillich insists that anyone who participates in these symbols is empowered by the Power of Being, which overcomes and conquers nonbeing and meaninglessness.

Tillich also further elaborated the thesis of the God above the God of theism in his Systematic Theology.

… (the God above the God of theism) This has been misunderstood as a dogmatic statement of a pantheistic or mystical character. First of all, it is not a dogmatic, but an apologetic, statement. It takes seriously the radical doubt experienced by many people. It gives one the courage of self - affirmation even in the extreme state of radical doubt.

— Tillich, Systematic Theology Vol. 2 , p.12

… In such a state the God of both religious and theological language disappears. But something remains, namely, the seriousness of that doubt in which meaning within meaninglessness is affirmed. The source of this affirmation of meaning within meaninglessness, of certitude within doubt, is not the God of traditional theism but the "God above God," the power of being, which works through those who have no name for it, not even the name God.

— Tillich, Systematic Theology Vol. 2 , p.12

Two of Tillich's works, The Courage to Be (1952) and Dynamics of Faith (1957), were read widely, even by people who do not normally read religious books. In The Courage to Be, he lists three basic anxieties: anxiety about our biological finitude, i.e., that arising from the knowledge that we will eventually die; anxiety about our moral finitude, linked to guilt; and anxiety about our existential finitude, a sense of aimlessness in life. Tillich related these to three different historical eras: the early centuries of the Christian era; the Reformation; and the 20th century. Tillich's popular works have influenced psychology as well as theology, having had an influence on Rollo May, whose "The Courage to Create" was inspired by "The Courage to Be".…This is the answer to those who ask for a message in the nothingness of their situation and at the end of their courage to be. But such an extreme point is not a space with which one can live. The dialectics of an extreme situation are a criterion of truth but not the basis on which a whole structure of truth can be built.

— Tillich, Systematic Theology Vol. 2 , p.12

Today Tillich’s most observable legacy may well be that of a spiritually - oriented public intellectual and teacher with a broad and continuing range of influence. Tillich‘s chapel sermons (especially at Union) were enthusiastically received (Tillich was known as the only faculty member of his day at Union willing to attend the revivals of Billy Graham). When Tillich was University Professor at Harvard he was chosen as keynote speaker from among an auspicious gathering of many who had appeared on the cover of Time Magazine during its first four decades. Tillich along with his student, psychologist Rollo May, was an early leader at the Esalen Institute. Contemporary New Age catchphrases describing God (spatially) as the "Ground of Being" and (temporally) as the "Eternal Now," in tandem with the view that God is not an entity among entities but rather is "Being - Itself" - notions which Eckhart Tolle, for example, has invoked repeatedly throughout his career - were pioneered by Tillich. The introductory philosophy course taught by the person Tillich considered to be his best student, John E. Smith, "probably turned more undergraduates to the study of philosophy at Yale than all the other philosophy courses put together. His courses in philosophy of religion and American philosophy defined those fields for many years. Perhaps most important of all, he has educated a younger generation in the importance of the public life in philosophy and in how to practice philosophy publicly.” In the 1980s and '90s the Boston University Institute for Philosophy and Religion, a leading forum dedicated to the revival of the American public tradition of philosophy and religion, flourished under the leadership of Tillich’s student and expositor Leroy S. Rouner.

- Martin Buber criticized Tillich's "transtheistic position" as a reduction of God to the impersonal "necessary being" of Thomas Aquinas.

- Tillich is not held in high regard by biblical literalists many of whom think of him not as a Christian, but a pantheist or atheist. The Elwell Evangelical Dictionary states, "At best Tillich was a pantheist, but his thought borders on atheism."