<Back to Index>

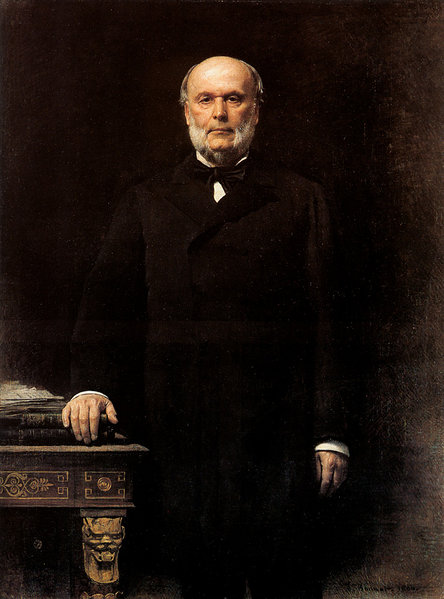

- President of the French Republic François Paul Jules Grévy, 1807

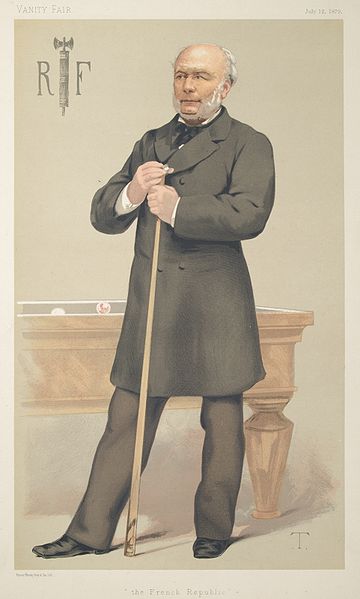

- Prime Minister of France Jules François Camille Ferry, 1832

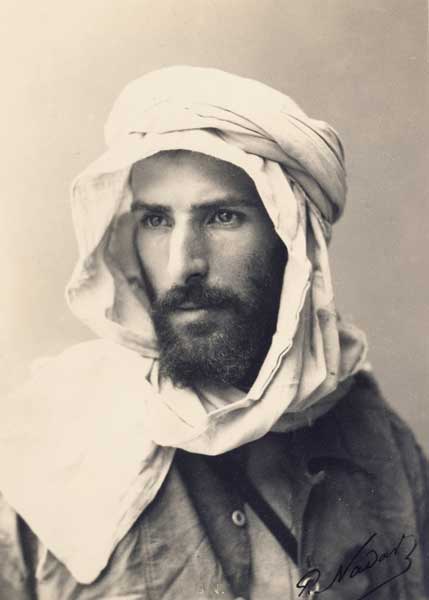

- Explorer Pierre Paul François Camille Savorgnan de Brazza, 1852

PAGE SPONSOR

François Paul Jules Grévy (15 August 1807 – 9 September 1891) was a President of the French Third Republic and one of the leaders of the Opportunist Republicans faction. Given that his predecessors were monarchists who tried without success to restore the French monarchy, Grévy is seen as the first real republican President of France.

Born at Mont - sous - Vaudrey in the Jura mountains, he became an advocate in 1837, and, having steadily maintained republican principles under the Orléans monarchy, was elected by his native department to the Constituent Assembly of 1848. Foreseeing that Louis Bonaparte would be elected president by the people, he proposed to vest the chief authority in a president of the Council elected and removable by the Assembly, or in other words, to suppress the Presidency of the Republic. After the coup d'état this proposition gained Grévy a reputation for sagacity, and upon his return to public life in 1868 he took a prominent place in the republican party.

After the fall of the Empire he was chosen president of the Assembly on 16 February 1871, and occupied this position until 2 April 1873, when he resigned on account of the opposition of the Right, which blamed him for having called one of its members to order in the session of the previous day. On 8 March 1876 he was elected president of the Chamber of Deputies, a post which he filled with such efficiency that upon the resignation of Marshal MacMahon he seemed to step naturally into the Presidency of the Republic (30 January 1879), and was elected without opposition by the republican parties.

Quiet, shrewd, attentive to the public interest and his own, but without any particular distinction, he would have left an unblemished reputation if he had not unfortunately accepted a second term (18 December 1885). Shortly afterwards the traffic of his son - in - law, Daniel Wilson, in the decorations of the Legion of Honor came to light. Grévy was not accused of personal participation in these scandals, but he was somewhat obstinate in refusing to realize that he was responsible indirectly for the use which his relative had made of the Elysée, and it had to be unpleasantly impressed upon him that his resignation was inevitable (2 December 1887).

He died at Mont - sous - Vaudrey on 9 September 1891. He owed both his success and his failure to the completeness with which he represented the particular type of the thrifty, generally sensible and patriotic, but narrow minded and frequently egoistic bourgeois.

In private life, Grévy was an ardent billiards player, and was featured in a portrait as a player in Vanity Fair magazine in 1879.

Grévy's zebra, a species of zebra, is named after him.

Jules François Camille Ferry (5 April 1832 – 17 March 1893) was a French statesman and republican. He was a promoter of laicism and colonial expansion.

Born in Saint-Dié, in the Vosges département, France, he studied law, and was called to the bar at Paris in 1854, but soon went into politics, contributing to various newspapers, particularly to Le Temps. He attacked the Second French Empire with great violence, directing his opposition especially against Baron Haussmann, prefect of the Seine département. A series of his articles in Le Temps were later republished as The Fantastic Tales of Haussmann (1868). Elected republican deputy for Paris in 1869, he protested against the declaration of war with Germany, and on 6 September 1870 was appointed prefect of the Seine by the Government of National Defense.

In this position he had the difficult task of administering Paris during the siege, and after the Paris Commune was obliged to resign (5 June 1871). From 1872 to 1873 he was sent by Adolphe Thiers as

minister to Athens, but returned to the chamber as deputy for the

Vosges, and became one of the leaders of the republican party. When the

first republican ministry was formed under WH Waddington on

4 February 1879, he was one of its members, and continued in the

ministry until 30 March 1885, except for two short interruptions (from

10 November 1881 to 30 January 1882, and from 29 July 1882 to 21

February 1883), first as minister of education and then as minister of

foreign affairs. A leader of the Opportunist Republicans faction, he was twice premier (1880 – 1881 and 1883 – 1885). He was a Freemason and a member of the Alsace - Lorraine Lodge founded in Paris in 1782.

Two important works are associated with his administration, the non - clerical organization of public education, and the beginning of the colonial expansion of France. Following the republican program he proposed to destroy the influence of the clergy in the university and found his own system of republican schooling. He reorganized the committee of public education (law of 27 February 1880), and proposed a regulation for the conferring of university degrees, which, though rejected, aroused violent polemics because the 7th article took away from the unauthorized religious orders the right to teach. He finally succeeded in passing his eponymous laws of 16 June 1881 and 28 March 1882, which made primary education in France free, non - clerical (laïque) and mandatory. In higher education, the number of professors, called the "hussards noirs de la République" ("Republic's black hussars") because of their Republican support, doubled under his ministry.

The education policies establishing French language as the language of the Republic have been contested in the second half of the 20th century insofar as, if they played an important role in unifying the French nation - state and the Third Republic, they also nearly provoked the extinction of several regional languages.

After the military defeat of France by Germany in 1870, Ferry formed the idea of acquiring a great colonial empire, principally for the sake of economic exploitation. In a speech before the Chamber of Deputies on 28 July 1885, he declared that "the superior races have a right because they have a duty: it is their duty to civilize the inferior races." Ferry directed the negotiations which led to the establishment of a French protectorate in Tunis (1881), prepared the treaty of 17 December 1885 for the occupation of Madagascar; directed the exploration of the Congo and of the Niger region; and above all, he organized the conquest of Annam and Tonkin in what became Indochina.

The last endeavor led to a war with the Manchu Empire, whose Qing Dynasty had a claim of suzerainty over the two provinces. The excitement caused in Paris by the sudden retreat of the French troops from Lang Son during this war led to the Tonkin Affair: his violent denunciation by Clemenceau and other radicals, and his downfall on 30 March 1885. Although the treaty of peace with the Manchu Empire (9 June 1885), in which the Qing Dynasty ceded suzerainty of Annam and Tonkin to France, was the work of his ministry, he would never again serve as premier.

The desire for a monarchy was still strong in France even under the Third Republic – the comte de Chambord having made a bid early in its history. A committed republican, Ferry proceeded to a wide scale "purge" by dismissing many known monarchists from top positions in the magistrature, army and civil and diplomatic service.

The key to understanding Ferry's unique position in Third Republic history is that until his political critic, Georges Clemenceau became Prime Minister twice in the 20th century Ferry has the longest tenure as Prime Minister under that regime. He also played with political dynamite that eventually destroyed his success. Ferry (like his 20th century equivalent Joseph Caillaux) believed in not confronting Wilhelmine Germany by threats of a future war of revenge. Most French politicians in the middle and right saw it as a sacred duty to one day lead France again against Germany to reclaim Alsace - Lorraine, and avenge the awful defeat of 1870. But Ferry realized that Germany was too powerful, and it made more sense to cooperate with Otto von Bismarck and avoid trouble. A sensible policy – but hardly popular.

Bismarck was constantly nervous about the situation with France. Although he had despised the ineptness of the French under Napoleon III and the government of Adolphe Thiers and Jules Favre, he had not planned for all the demands he presented the French in 1870. He only wished to temporarily cripple France by the billion franc reparation, but suddenly he was confronted by the demands of Marshals Albrecht von Roon and Helmut von Moltke (backed by Emperor Wilhelm I) to annex the two French provinces as further payment. Bismarck, for all his abilities regarding manipulating events, could not afford to anger the Prussian military. He got the two provinces, but he realized it would eventually have severe future repercussions.

Bismarck was able to ignore the French for most of the 1870s and early 1880s, but as he found problems with his three erstwhile allies (Austria, Russia, and Italy) he realized France might one day take advantage of this (as it did with Russia in 1894). When Ferry came up with a radically different approach to the situation and offered an olive branch Bismarck reciprocated. A Franco - German friendship would alleviate problems of siding with either Austria or Russia, or Austria and Italy. Bismarck approved of the colonial expansion that France pursued under Ferry. He only had some problems with local German imperialists who were critical that Germany lacked colonies, so he found a few in the 1880s, making certain he did not confront French interests. But he also suggested Franco - German cooperation on the imperial front against the British Empire, thus hoping to create a wedge between the two Western European great powers. It did as a result, leading to a major race for influence across Africa that nearly culminated in war in the next decade, at Fashoda in the Sudan in 1898. But by then both Bismarck and Ferry were dead, and the rapproachment policy died when Ferry lost office. As for Fashoda, while it was a confrontation, it led to Britain and France eventually discussing their rival colonial goals, and agreeing to support each other's sphere of influence – the first step to the Entente Cordiale between the countries in 1904.

Ferry remained an influential member of the moderate republican party, and directed the opposition to General Boulanger. After the resignation of Jules Grévy (2 December 1887), he was a candidate for the presidency of the republic, but the radicals refused to support him, and he withdrew in favour of Sadi Carnot.

On 10 December 1887, a

man named Aubertin attempted to assassinate Jules Ferry, who later died

from complications attributed to this wound on 17 March 1893. The Chamber of Deputies gave him a state funeral.

Pietro Paolo Savorgnan di Brazzà, best known as Pierre Paul François Camille Savorgnan de Brazza (Castel Gandolfo (Rome), January 26, 1852 - Dakar September 14, 1905), was a Franco - Italian explorer, born in Italy and later naturalized Frenchman. With the backing of the Société de Géographie de Paris, he opened up for France entry along the right bank of the Congo that eventually led to French colonies in Central Africa. His easy manner and great physical charm, as well as his pacific approach among Africans, were his trademarks. Under French colonial rule Brazzaville, the capital of the Republic of the Congo, was named after him and the name was retained by the post - colonial rulers.

Born in Rome on 26 January 1852, Pietro Savorgnan di Brazzà was the seventh son of Count Ascanio Savorgnan di Brazzà, a nobleman of Udine with many French connections and his wife Giacinta Simonetti. Pietro was interested in exploration from an early age and won entry to the French naval school at Brest. He graduated as an ensign and sailed on the French ship Jeanne d'Arc to Algeria.

His next ship was the Venus, which stopped at Gabon regularly and in 1874 Brazza made two trips, up the Gabon River and Ogoue River (Ogowe River). He then proposed to the government that he explore the Ogoue to its source. With the help of friends in high places, including Jules Ferry and Leon Gambetta, he secured partial funding, the rest coming out of his own pocket. He also became a naturalized French citizen at this time, adopting the French spelling of his name.

In this expedition, which lasted from 1875 – 1878, 'armed' only with cotton textiles and tools to use for barter, and accompanied by Noel Ballay, a doctor, naturalist Alfred Marche, a sailor, thirteen Senegalese laptots and four local interpreters, Brazza charmed and talked his way deep inland.

The French authorized a second mission, 1879 - 1882. By following the Ogoue River upstream and proceeding overland to the Lefini River and then downstream, Brazza succeeded in reaching the Congo River in 1880 without encroaching on Portuguese claims. He then proposed to King Makoko of the Batekes that he place his kingdom under the protection of the French flag. Makoko, interested in trade possibilities and in gaining an edge over his rivals, signed the treaty. Makoko also arranged for the establishment of a French settlement at Mfoa on the Congo's Malebo Pool, a place later known as Brazzaville; after Brazza's departure, the outpost was manned by two laptots under the command of Senegalese Sergeant Malamine Camara, whose resourcefulness had impressed Brazza during their several months trekking inland from the coast. During this trip he encountered Stanley near Vivi. Brazza did not reveal that he just signed up Makoko and it took Stanley some months before he realized that he (and his sponsor King Léopold) had been beaten in the 'race'.

In 1883, Brazza was named governor general of the French Congo. Journalists' reports of the decent wages and humane conditions there contrasted with the personal regime of Belgian King Léopold on the opposite bank in the Congo Free State. This, combined with the poor profitability of the new colony, made Brazza some important enemies and a mounting smear campaign in the French press led to his dismissal in 1897.

By 1905, stories were reaching Paris of injustice, forced labor and brutality by the Congo's new governor, Emile Gentil, in conjunction with the new concession companies imposed by the French Colonial Office and condoned by Auguoard, Catholic Bishop of the Congo. Brazza was sent to investigate, and produced a damming report in spite of many obstructions placed in his path. When his deputy Félicien Challaye brought the embarrassing report in front of the National Assembly it was suppressed and those oppressive conditions remained in the French Congo for decades.

The tour of the Congo took a hard physical toll of Brazza, and on his return journey to Dakar he

died of dysentery and fever. There were rumors that he had been

poisoned. His body was repatriated to France and he was given a state

funeral at Sainte - Clothilde Church in Paris prior to interment at the cemetery of Père Lachaise.

His widow, Thérèse, dissatisfied with the politicians'

subsequent behavior, had his body exhumed and reinterred in the African

continent at Algiers. The epitaph for his burial site in Algiers reads: "une mémoire pure de sang humain" ("a memory untainted by human blood").

In February 2005 the Presidents of Congo, of Gabon and of France, gathered at a ceremony to lay the foundation stone for a memorial to Pierre de Brazza, a mausoleum of Italian marble.

On 30 September 2006, de Brazza's remains were exhumed from Algiers along with those of his wife and four children. They were reinterred in Brazzaville on 3 October, in the new marble mausoleum which had been prepared for them and had cost some 10 million dollars. The ceremony was attended by three African presidents and a French foreign minister, who paid tribute to his humanitarian work against slavery and the abuse of African workers.

The decision to honor de Brazza as a founding father of the Republic of the Congo has elicited protests among many Congolese, questioning the best use of the money and why a colonizer should be revered as a national hero instead of the Congolese who fought against colonization. Historian Théophile Obenga stated that in honoring de Brazza, the government disregarded salient information, including an account of de Brazza's rape of a Congolese woman passed down by oral tradition.