<Back to Index>

- Queen of the United Kingdom Victoria, 1819

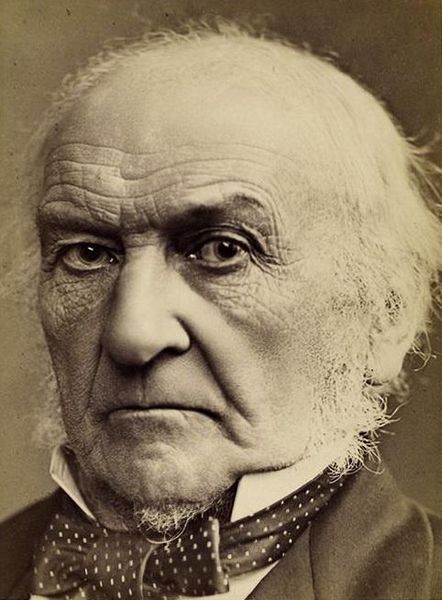

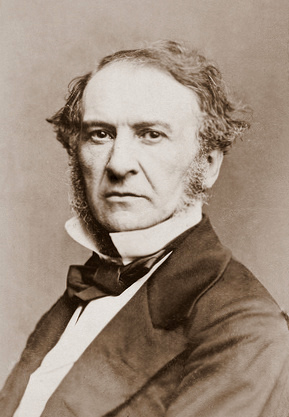

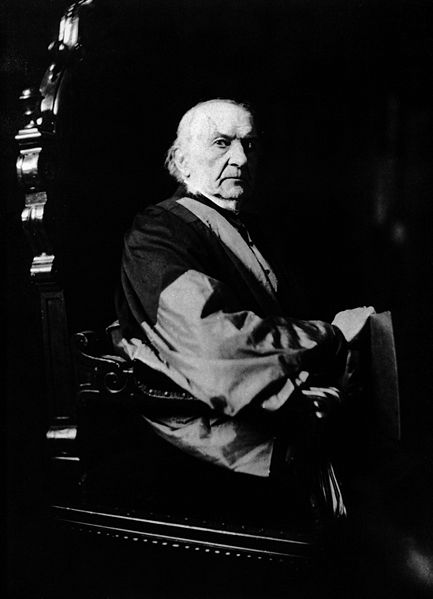

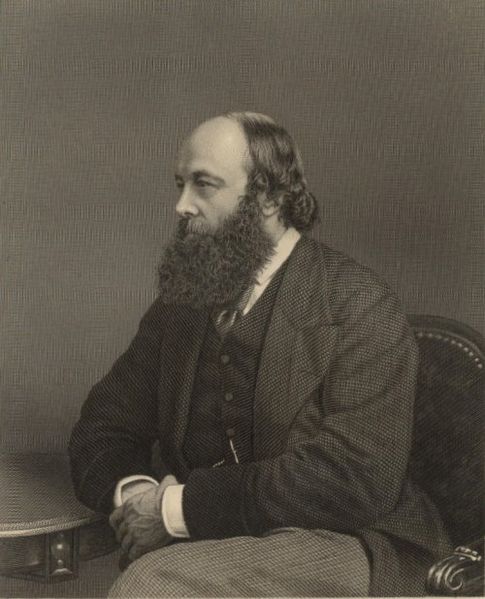

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom William Ewart Gladstone, 1809

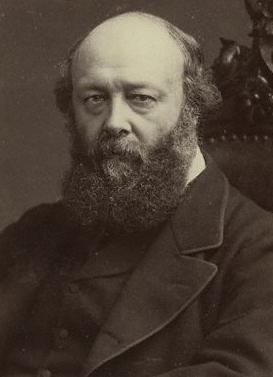

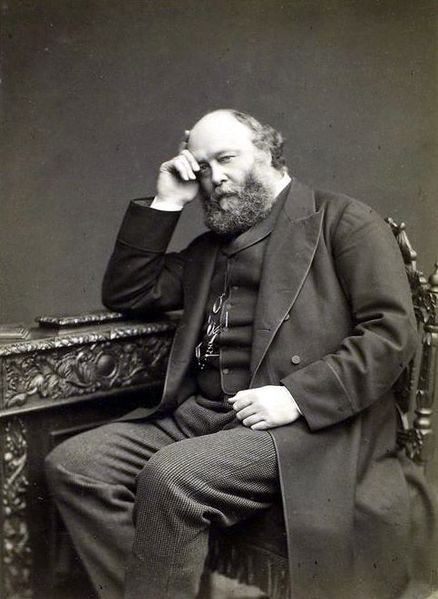

- Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne - Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, 1830

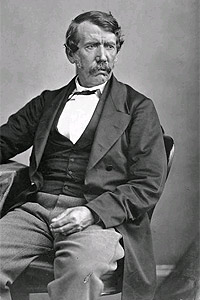

- Missionary and Explorer David Livingstone, 1813

PAGE SPONSOR

Queen Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India.

Victoria was the daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, the fourth son of King George III. Both the Duke of Kent and the King died in 1820, and Victoria was raised under close supervision by her German born mother Princess Victoria of Saxe - Coburg - Saalfeld. She inherited the throne at the age of 18 after her father's three elder brothers died without surviving legitimate issue. The United Kingdom was already an established constitutional monarchy, in which the Sovereign held relatively few direct political powers. Privately, she attempted to influence government policy and ministerial appointments. Publicly, she became a national icon, and was identified with strict standards of personal morality.

She married her first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe - Coburg and Gotha, in 1840. Their nine children and 26 of their 34 grandchildren who survived childhood married into royal and noble families across the continent, tying them together and earning her the nickname "the grandmother of Europe". After Albert's death in 1861, Victoria plunged into deep mourning and avoided public appearances. As a result of her seclusion, republicanism temporarily gained strength, but in the latter half of her reign, her popularity recovered. Her Golden and Diamond Jubilees were times of public celebration.

Her reign of 63 years and 7 months, which is longer than that of any other British monarch and the longest of any female monarch in history, is known as the Victorian era. It was a period of industrial, cultural, political, scientific, and military change within the United Kingdom, and was marked by a great expansion of the British Empire. She was the last British monarch of the House of Hanover; her son and successor Edward VII belonged to the House of Saxe - Coburg and Gotha.

Victoria's father was Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn, the fourth son of the reigning King of the United Kingdom, George III. Until 1817, Edward's niece, Princess Charlotte of Wales,

was the only legitimate grandchild of George III. Her death in

1817 precipitated a succession crisis in the United Kingdom that brought

pressure on the Duke of Kent to marry and have children. In 1818, he

married Princess Victoria of Saxe - Coburg - Saalfeld, a German princess whose brother Leopold was

the widower of Princess Charlotte. The Duke and Duchess of Kent's only

child, Victoria, was born at 4.15 am on 24 May 1819 at Kensington Palace in London.

She was christened privately by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Manners - Sutton, on 24 June 1819 in the Cupola Room at Kensington Palace. She was baptized Alexandrina, after one of her godparents, Emperor Alexander I of Russia, and Victoria after her mother. Additional names proposed by her parents — Georgina (or Georgiana), Charlotte and Augusta — were dropped on the instructions of the Duke's elder brother, the Prince Regent (later George IV).

At birth, Victoria was fifth in the line of succession after her father and his three older brothers: the Prince Regent, the Duke of York, and the Duke of Clarence (later William IV). The Prince Regent was estranged from his wife and the Duchess of York was 52 years old, so the two eldest brothers were unlikely to have any further children. The Dukes of Kent and Clarence married on the same day 12 months before Victoria's birth, but both of Clarence's daughters (born in 1819 and 1820 respectively) died as infants. Victoria's grandfather and father died in 1820, within a week of each other, and the Duke of York died in 1827. On the death of her uncle George IV in 1830, she became heiress presumptive to her next surviving uncle, William IV. The Regency Act 1830 made special provision for the Duchess of Kent to act as regent in case William died while Victoria was still a minor. King William distrusted the Duchess's capacity to be regent, and in 1836 declared in her presence that he wanted to live until Victoria's 18th birthday, so that a regency could be avoided.

Victoria later described her childhood as "rather melancholy". Her mother was extremely protective, and Victoria was raised largely isolated from other children under the so called "Kensington System", an elaborate set of rules and protocols devised by the Duchess and her ambitious and domineering comptroller, Sir John Conroy, who was rumored to be the Duchess's lover. The

system prevented the princess from meeting people whom her mother and

Conroy deemed undesirable (including most of her father's family), and

was designed to render her weak and dependent upon them. The Duchess avoided the court because she was scandalized by the presence of the King's bastard children, and perhaps prompted the emergence of Victorian morality by insisting that her daughter avoid any appearance of sexual impropriety. Victoria

shared a bedroom with her mother every night, studied with private

tutors to a regular timetable, and spent her play hours with her dolls

and her King Charles spaniel, Dash. Her lessons included French, German, Italian, and Latin, but she spoke only English at home.

In 1830, the Duchess of Kent and Conroy took Victoria across the center of England to visit the Malvern Hills, stopping at towns and great country houses along the way. Similar journeys to other parts of England and Wales were taken in 1832, 1833, 1834 and 1835. To King William's annoyance, Victoria was enthusiastically welcomed in each of the stops. William compared the journeys to royal progresses and was concerned that they portrayed Victoria as his rival rather than his heiress presumptive. Victoria disliked the trips; the constant round of public appearances made her tired and ill, and there was little time for her to rest. She objected on the grounds of the King's disapproval, but her mother dismissed his complaints as motivated by jealousy, and forced Victoria to continue the tours. At Ramsgate in October 1835, Victoria contracted a severe fever, which Conroy initially dismissed as a childish pretense. While Victoria was ill, Conroy and the Duchess unsuccessfully badgered her to make Conroy her private secretary. As a teenager, Victoria resisted persistent attempts by her mother and Conroy to appoint him to her staff. Once Queen, she banned him from her presence, but he remained in her mother's household.

By 1836, the Duchess's brother, Leopold, who had been King of the Belgians since 1831, hoped to marry his niece to his nephew, Prince Albert of Saxe - Coburg and Gotha. Leopold, Victoria's mother, and Albert's father (Ernest I, Duke of Saxe - Coburg and Gotha) were siblings. Leopold arranged for Victoria's mother to invite her Coburg relatives to visit her in May 1836, with the purpose of introducing Victoria to Albert. William IV, however, disapproved of any match with the Coburgs, and instead favored the suit of Prince Alexander of the Netherlands, second son of the Prince of Orange. Victoria was aware of the various matrimonial plans and critically appraised a parade of eligible princes. According to her diary, she enjoyed Albert's company from the beginning. After the visit she wrote, "[Albert] is extremely handsome; his hair is about the same color as mine; his eyes are large and blue, and he has a beautiful nose and a very sweet mouth with fine teeth; but the charm of his countenance is his expression, which is most delightful." Alexander, on the other hand, was "very plain".

Victoria wrote to her uncle Leopold, whom Victoria considered her "best and kindest adviser", to thank him "for the prospect of great

happiness you have contributed to give me, in the person of dear

Albert ...

He possesses every quality that could be desired to render me perfectly

happy. He is so sensible, so kind, and so good, and so amiable too. He

has besides the most pleasing and delightful exterior and appearance you

can possibly see." However

at 17, Victoria, though interested in Albert, was not yet ready to

marry. The parties did not undertake a formal engagement, but assumed

that the match would take place in due time.

Victoria turned 18 on 24 May 1837, and a regency was avoided. On 20 June 1837, William IV died at the age of 71, and Victoria became Queen of the United Kingdom. In her diary she wrote, "I was awoke at 6 o'clock by Mamma, who told me the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Conyngham were here and wished to see me. I got out of bed and went into my sitting room (only in my dressing gown) and alone, and saw them. Lord Conyngham then acquainted me that my poor Uncle, the King, was no more, and had expired at 12 minutes past 2 this morning, and consequently that I am Queen." Official documents prepared on the first day of her reign described her as Alexandrina Victoria, but the first name was withdrawn at her own wish and not used again.

Since 1714, Britain had shared a monarch with Hanover in Germany, but under Salic law women

were excluded from the Hanoverian succession. While Victoria inherited

all the British dominions, Hanover passed instead to her father's

younger brother, her unpopular uncle the Duke of Cumberland and

Teviotdale, who became King Ernest Augustus I of Hanover. He was her heir presumptive until she married and had a child.

At the time of her accession, the government was led by the Whig prime minister Lord Melbourne, who at once became a powerful influence on the politically inexperienced Queen, who relied on him for advice. Charles Greville supposed that the widowed and childless Melbourne was "passionately fond of her as he might be of his daughter if he had one", and Victoria probably saw him as a father figure. Her coronation took place on 28 June 1838, and she became the first sovereign to take up residence at Buckingham Palace. She inherited the revenues of the duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall, and was granted a civil list of £385,000 per year. Financially prudent, she paid off her father's debts.

At the start of her reign Victoria was popular, but her reputation suffered in an 1839 court intrigue when one of her mother's ladies - in - waiting, Lady Flora Hastings, developed an abdominal growth that was widely rumored to be an out - of - wedlock pregnancy by Sir John Conroy. Victoria believed the rumors. She hated Conroy, and despised "that odious Lady Flora", because she had conspired with Conroy and the Duchess of Kent in the Kensington System. At first, Lady Flora refused to submit to a naked medical examination, until in mid February she eventually agreed, and was found to be a virgin. Conroy, the Hastings family and the opposition Tories organized a press campaign implicating the Queen in the spreading of false rumors about Lady Flora. When Lady Flora died in July, the post - mortem revealed a large tumor on her liver that had distended her abdomen. At public appearances, Victoria was hissed and jeered as "Mrs. Melbourne".

In 1839, Melbourne resigned after Radicals and Tories (both of whom Victoria detested) voted against a Bill to suspend the constitution of Jamaica. The Bill removed political power from plantation owners who were resisting measures associated with the abolition of slavery. The Queen commissioned a Tory, Sir Robert Peel, to form a new ministry. At the time, it was customary for the prime minister to appoint members of the Royal Household, who were usually his political allies and their spouses. Many of the Queen's Ladies of the Bedchamber were wives of Whigs, and Peel expected to replace them with wives of Tories. In what became known as the bedchamber crisis,

Victoria, advised by Melbourne, objected to their removal. Peel refused

to govern under the restrictions imposed by the Queen, and consequently

resigned his commission, allowing Melbourne to return to office.

Though queen, as an unmarried young woman Victoria was required by social convention to live with her mother, despite their differences over the Kensington System and her mother's continued reliance on Conroy. Her mother was consigned to a remote apartment in Buckingham Palace, and Victoria often refused to meet her. When Victoria complained to Melbourne that her mother's close proximity promised "torment for many years", Melbourne sympathized but said it could be avoided by marriage, which Victoria called a "schocking [sic] alternative". She showed interest in Albert's education for the future role he would have to play as her husband, but she resisted attempts to rush her into wedlock.

Victoria continued to praise Albert following his second visit in October 1839. Albert and Victoria felt mutual affection and the Queen proposed to him on 15 October 1839, just five days after he had arrived at Windsor. They were married on 10 February 1840, in the Chapel Royal of St. James's Palace, London. Victoria was besotted. She spent the evening after their wedding lying down with a headache, but wrote ecstatically in her diary:

I NEVER, NEVER spent such an evening!!! MY DEAREST DEAREST DEAR Albert ... his excessive love & affection gave me feelings of heavenly love & happiness I never could have hoped to have felt before! He clasped me in his arms, & we kissed each other again & again! His beauty, his sweetness & gentleness – really how can I ever be thankful enough to have such a Husband! ... to be called by names of tenderness, I have never yet heard used to me before – was bliss beyond belief! Oh! This was the happiest day of my life!

Albert

became an important political adviser as well as the Queen's companion,

replacing Lord Melbourne as the dominant, influential figure in the first half of her life. Victoria's mother was evicted from the palace, to Ingestre House in Belgrave Square. After the death of Princess Augusta in 1840, Victoria's mother was given both Clarence and Frogmore Houses. Through Albert's mediation, relations between mother and daughter slowly improved.

During Victoria's first pregnancy in 1840, in the first few months of the marriage, 18 year old Edward Oxford attempted to assassinate her while she was riding in a carriage with Prince Albert on her way to visit her mother. Oxford fired twice, but both bullets missed. He was tried for high treason and found guilty, but was acquitted on the grounds of insanity. In the immediate aftermath of the attack, Victoria's popularity soared, mitigating residual discontent over the Hastings affair and the bedchamber crisis. Her daughter, also named Victoria, was born on 21 November 1840. The Queen hated being pregnant, viewed breast feeding with disgust, and thought newborn babies were ugly. Nevertheless, she and Albert had a further eight children.

Victoria's household was largely run by her childhood governess, Baroness Louise Lehzen from Hanover. Lehzen had been a formative influence on Victoria, and had supported her against the Kensington System. Albert,

however, thought Lehzen was incompetent, and that her mismanagement

threatened the health of his daughter. After a furious row between

Victoria and Albert over the issue, Lehzen was pensioned off, and

Victoria's close relationship with her ended.

On 29 May 1842, Victoria was riding in a carriage along The Mall, London, when John Francis aimed a pistol at her but did not fire; he escaped. The following day, Victoria drove the same route, though faster and with a greater escort, in a deliberate attempt to provoke Francis to take a second aim and catch him in the act. As expected, Francis shot at her, but he was seized by plain clothes policemen, and convicted of high treason. On 3 July, two days after Francis's death sentence was commuted to transportation for life, John William Bean also fired a pistol at the Queen, but it was loaded only with paper and tobacco. Oxford felt that the attempts were encouraged by his acquittal in 1840. Bean was sentenced to 18 months in jail. In a similar attack in 1849, unemployed Irishman William Hamilton fired a powder - filled pistol at Victoria's carriage as it passed along Constitution Hill, London. In 1850, the Queen did sustain injury when she was assaulted by a possibly insane ex-army officer, Robert Pate. As Victoria was riding in a carriage, Pate struck her with his cane, crushing her bonnet and bruising her face. Both Hamilton and Pate were sentenced to seven years' transportation.

Melbourne's support in the House of Commons weakened through the early years of Victoria's reign, and in the 1841 general election the Whigs were defeated. Peel became prime minister, and the Ladies of the Bedchamber most associated with the Whigs were replaced.

In 1845, Ireland was hit by a potato blight. In the next four years over a million Irish people died and another million emigrated in what became known as the Great Famine. In Ireland, Victoria was labelled "The Famine Queen". She personally donated £2,000 to famine relief, more than any other individual donor, and also supported the Maynooth Grant to a Roman Catholic seminary in Ireland, despite Protestant opposition. The story that she donated only £5 in aid to the Irish, and on the same day gave the same amount to Battersea Dogs Home, was a myth generated towards the end of the 19th century.

By 1846, Peel's ministry faced a crisis involving the repeal of the Corn Laws. Many Tories — by then known also as Conservatives — were

opposed to the repeal, but Peel, some Tories (the "Peelites"), most

Whigs and Victoria supported it. Peel resigned in 1846, after the repeal

narrowly passed, and was replaced by Lord John Russell.

Internationally, Victoria took a keen interest in the improvement of relations between France and Britain. She made and hosted several visits between the British royal family and the House of Orleans, who were related by marriage through the Coburgs. In 1843 and 1845, she and Albert stayed with King Louis Philippe I at château d'Eu in Normandy; she was the first British or English monarch to visit a French one since the meeting of Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France on the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520. When Louis Philippe made a reciprocal trip in 1844, he became the first French king to visit a British sovereign. Louis Philippe was deposed in the revolutions of 1848, and fled to exile in England. At the height of a revolutionary scare in the United Kingdom in April 1848, Victoria and her family left London for the greater safety of Osborne House, a private estate on the Isle of Wight that they had purchased in 1845 and redeveloped. Demonstrations by Chartists and Irish nationalists failed to attract widespread support, and the scare died down without any major disturbances. Victoria's first visit to Ireland in 1849 was a public relations success, but it had no lasting impact or effect on the growth of Irish nationalism.

Russell's ministry, though Whig, was not favored by the Queen. She found particularly offensive the Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, who often acted without consulting the Cabinet, the Prime Minister, or the Queen. Victoria complained to Russell that Palmerston sent official dispatches to foreign leaders without her knowledge, but Palmerston was retained in office and continued to act on his own initiative, despite her repeated remonstrances. It was only in 1851 that Palmerston was removed after he announced the British government's approval of President Louis - Napoleon Bonaparte's coup in France without consulting the Prime Minister. The following year, President Bonaparte was declared Emperor Napoleon III, by which time Russell's administration had been replaced by a short lived minority government led by Lord Derby.

In 1853, Victoria gave birth to her eighth child, Leopold, with the aid of the new anaesthetic, chloroform. Victoria was so impressed by the relief it gave from the pain of childbirth that she used it again in 1857 at the birth of her ninth and final child, Beatrice, despite opposition from members of the clergy, who considered it against biblical teaching, and members of the medical profession, who thought it dangerous. Victoria may have suffered from post natal depression after many of her pregnancies. Letters from Albert to Victoria intermittently complain of her loss of self control. For example, about a month after Leopold's birth Albert complained in a letter to Victoria about her "continuance of hysterics" over a "miserable trifle".

In early 1855, the government of Lord Aberdeen, who had replaced Derby, fell amidst recriminations over the poor management of British troops in the Crimean War. Victoria approached both Derby and Russell to form a ministry, but neither had sufficient support, and Victoria was forced to appoint Palmerston as prime minister.

Napoleon III, since the Crimean War Britain's closest ally, visited London in April 1855, and from 17 to 28 August the same year Victoria and Albert returned the visit. Napoleon III met the couple at Dunkirk and accompanied them to Paris. They visited the Exposition Universelle (a successor to Albert's 1851 brainchild the Great Exhibition) and Napoleon I's tomb at Les Invalides (to which his remains had only been returned in 1840), and were guests of honor at a 1,200 guest ball at the Palace of Versailles.

On 14 January 1858, an Italian refugee from Britain called Orsini attempted to assassinate Napoleon III with a bomb made in England. The ensuing diplomatic crisis destabilized the government, and Palmerston resigned. Derby was reinstated as prime minister. Victoria and Albert attended the opening of a new basin at the French military port of Cherbourg on 5 August 1858, in an attempt by Napoleon III to reassure Britain that his military preparations were directed elsewhere. On her return Victoria wrote to Derby reprimanding him for the poor state of the Royal Navy in comparison to the French one. Derby's ministry did not last long, and in June 1859 Victoria recalled Palmerston to office.

Eleven days after Orsini's assassination attempt in France, Victoria's eldest daughter married Prince Frederick William of Prussia in

London. They had been betrothed since September 1855, when Princess

Victoria was 14 years old; the marriage was delayed by the Queen and

Prince Albert until the bride was 17. The Queen and Albert hoped that their daughter and son - in - law would be a liberalizing influence in the enlarging Prussian state. Victoria

felt "sick at heart" to see her daughter leave England for Germany; "It

really makes me shudder", she wrote to Princess Victoria in one of her

frequent letters, "when I look round to all your sweet, happy,

unconscious sisters, and think I must give them up too – one by one." Almost exactly a year later, Princess Victoria gave birth to the Queen's first grandchild: Wilhelm.

In March 1861, Victoria's mother died, with Victoria at her side. Through reading her mother's papers, Victoria discovered that her mother had loved her deeply; she was heart broken, and blamed Conroy and Lehzen for "wickedly" estranging her from her mother. To relieve his wife during her intense and deep grief, Albert took on most of her duties, despite being ill himself with chronic stomach trouble. In August, Victoria and Albert visited their son, the Prince of Wales, who was attending army maneuvers near Dublin, and spent a few days holiday in Killarney. In November, Albert was made aware of gossip that his son had slept with an actress in Ireland. Appalled, Albert traveled to Cambridge, where his son was studying, to confront him. By the beginning of December, Albert was very unwell. He was diagnosed with typhoid fever by William Jenner, and died on 14 December 1861. Victoria was devastated. She blamed her husband's death on worry over the Prince of Wales's philandering. He had been "killed by that dreadful business", she said. She entered a state of mourning and wore black for the remainder of her life. She avoided public appearances, and rarely set foot in London in the following years. Her seclusion earned her the name "widow of Windsor".

Victoria's

self imposed isolation from the public diminished the popularity of the

monarchy, and encouraged the growth of the republican movement. She did undertake her official government duties, yet chose to remain secluded in her royal residences — Windsor Castle, Osborne House, and the private estate in Scotland that she and Albert had acquired in 1847, Balmoral Castle. In March 1864, a protester stuck a notice on the railings of Buckingham Palace that announced "these commanding premises to be let or sold in consequence of the late occupant's declining business". Her uncle Leopold wrote to her advising her to appear in public. She agreed to visit the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society at Kensington and take a drive through London in an open carriage.

Through the 1860s, Victoria relied increasingly on a manservant from Scotland, John Brown. Slanderous rumors of a romantic connection and even a secret marriage appeared in print, and the Queen was referred to as "Mrs Brown". The story of their relationship was the subject of the 1997 movie Mrs. Brown. A painting by Edwin Landseer depicting the Queen with Brown was exhibited at the Royal Academy, and Victoria published a book, Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands, which featured Brown prominently and in which the Queen praised him highly.

Palmerston died in 1865, and after a brief ministry led by Russell, Derby returned to power. In 1866, Victoria attended the State Opening of Parliament for the first time since Albert's death. The following year she supported the passing of the Reform Act 1867 which doubled the electorate by extending the franchise to many urban working men, though she was not in favor of votes for women. Derby resigned in 1868, to be replaced by Benjamin Disraeli, who charmed Victoria. "Everyone likes flattery," he said, "and when you come to royalty you should lay it on with a trowel." With the phrase "we authors, Ma'am", he complimented her. Disraeli's ministry only lasted a matter of months, and at the end of the year his Liberal rival, William Ewart Gladstone, was appointed prime minister. Victoria found Gladstone's demeanor far less appealing; he spoke to her, she was supposed to have complained, as though she was "a public meeting rather than a woman".

In 1870, republican sentiment in Britain, fed by the Queen's seclusion, was boosted after the establishment of the Third French Republic. A republican rally in Trafalgar Square demanded Victoria's removal, and Radical MPs spoke against her. In August and September 1871, she was seriously ill with an abscess in her arm, which Joseph Lister successfully lanced and treated with his new anti - septic carbolic acid spray. In late November 1871, at the height of the republican movement, the Prince of Wales contracted typhoid fever, the disease that was believed to have killed his father, and Victoria was fearful her son would die. As the tenth anniversary of her husband's death approached, her son's condition grew no better, and Victoria's distress continued. To general rejoicing, he pulled through. Mother and son attended a public parade through London and a grand service of thanksgiving in St Paul's Cathedral on 27 February 1872, and republican feeling subsided.

On

the last day of February 1872, two days after the thanksgiving service,

17 year old Arthur O'Connor (great - nephew of Irish MP Feargus O'Connor) waved an unloaded pistol at Victoria's open carriage as it drove

through the gates of Buckingham Palace. Brown, who was attending the

Queen, grabbed him and O'Connor was later sentenced to 12 months'

imprisonment. As a result of the incident, Victoria's popularity recovered further.

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British East India Company, which had ruled much of India, was dissolved, and Britain's possessions and protectorates on the Indian subcontinent were formally incorporated into the British Empire. The Queen had a relatively balanced view of the conflict, and condemned atrocities on both sides. She wrote of "her feelings of horror and regret at the result of this bloody civil war", and insisted, urged on by Albert, that an official proclamation announcing the transfer of power from the company to the state "should breathe feelings of generosity, benevolence and religious toleration". At her behest, a reference threatening the "undermining of native religions and customs" was replaced by a passage guaranteeing religious freedom.

In the 1874 general election, Disraeli was returned to power. He passed the Public Worship Regulation Act 1874, which removed Catholic rituals from the Anglican liturgy and which Victoria strongly supported. She preferred short, simple services, and personally considered herself more aligned with the Presbyterian Church of Scotland than the Episcopalian Church of England. He also pushed the Royal Titles Act 1876 through Parliament, so that Victoria took the title "Empress of India" from 1 May 1876. The new title was proclaimed at the Delhi Durbar of 1 January 1877.

On 14 December 1878, the anniversary of Albert's death, Victoria's second daughter Alice, who had married Louis of Hesse, died of diphtheria in Darmstadt. Victoria noted the coincidence of the dates as "almost incredible and most mysterious". In May 1879, she became a great - grandmother (on the birth of Princess Feodora of Saxe - Meiningen) and passed her "poor old 60th birthday". She felt "aged" by "the loss of my beloved child".

Between

April 1877 and February 1878, she threatened five times to abdicate

while pressuring Disraeli to act against Russia during the Russo - Turkish War, but her threats had no impact on the events or their conclusion with the Congress of Berlin. Disraeli's expansionist foreign policy, which Victoria endorsed, led to conflicts such as the Anglo - Zulu War and the Second Anglo - Afghan War. "If we are to maintain our position as a first - rate Power", she wrote, "we must … be Prepared for attacks and wars, somewhere or other, CONTINUALLY."

Victoria saw the expansion of the British Empire as civilizing and

benign,

protecting native peoples from more aggressive powers or cruel rulers:

"It is not in our custom to annexe countries", she said, "unless we are

obliged & forced to do so." To Victoria's dismay, Disraeli lost the 1880 general election, and Gladstone returned as prime minister. When Disraeli died the following year, she was blinded by "fast falling tears", and erected a memorial tablet "placed by his grateful Sovereign and Friend, Victoria R.I."

On 2 March 1882, Roderick Maclean, a disgruntled poet apparently offended by Victoria's refusal to accept one of his poems, shot at the Queen as her carriage left Windsor railway station. Two schoolboys from Eton College struck him with their umbrellas, until he was hustled away by a policeman. Victoria was outraged when he was found not guilty by reason of insanity, but was so pleased by the many expressions of loyalty after the attack that she said it was "worth being shot at — to see how much one is loved".

On 17 March 1883, she fell down some stairs at Windsor, which left her lame until July; she never fully recovered and was plagued with rheumatism thereafter. Brown died 10 days after her accident, and to the consternation of her private secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, Victoria began work on a eulogistic biography of Brown. Ponsonby and Randall Davidson, Dean of Windsor, who had both seen early drafts, advised Victoria against publication, on the grounds that it would stoke the rumors of a love affair. The manuscript was destroyed. In early 1884, Victoria did publish More Leaves from a Journal of a Life in the Highlands, a sequel to her earlier book, which she dedicated to her "devoted personal attendant and faithful friend John Brown". On the day after the first anniversary of Brown's death, Victoria was informed by telegram that her youngest son, Leopold, had died in Cannes. He was "the dearest of my dear sons", she lamented. The following month, Victoria's youngest child, Beatrice, met and fell in love with Prince Henry of Battenberg at the wedding of Victoria's granddaughter Princess Victoria of Hesse and by Rhine to Henry's brother Prince Louis of Battenberg. Beatrice and Henry planned to marry, but Victoria opposed the match at first, wishing to keep Beatrice at home to act as her companion. After a year, she was won around to the marriage by Henry and Beatrice's promise to remain living with and attending her.

Victoria was pleased when Gladstone resigned in 1885 after his budget was defeated. She thought his government was "the worst I have ever had", and blamed him for the death of General Gordon at Khartoum. Gladstone was replaced by Lord Salisbury.

Salisbury's government only lasted a few months, however, and Victoria

was forced to recall Gladstone, whom she referred to as a "half crazy

& really in many ways ridiculous old man". Gladstone attempted to pass a bill granting Ireland home rule, but to Victoria's glee it was defeated. In the ensuing election, Gladstone's party lost to Salisbury's and the government switched hands again.

In 1887, the British Empire celebrated Victoria's Golden Jubilee. Victoria marked the fiftieth anniversary of her accession on 20 June with a banquet to which 50 kings and princes were invited. The following day, she participated in a procession that, in the words of Mark Twain, "stretched to the limit of sight in both directions" and attended a thanksgiving service in Westminster Abbey. By this time, Victoria was once again extremely popular. Two days later on 23 June, she engaged two Indian Muslims as waiters, one of whom was Abdul Karim. He was soon promoted to "Munshi": teaching her Hindi - Urdu, and acting as a clerk. Her family and retainers were appalled, and accused Abdul Karim of spying for the Muslim Patriotic League, and biasing the Queen against the Hindus. Equerry Frederick Ponsonby (the son of Sir Henry) discovered that the Munshi had lied about his parentage, and reported to Lord Elgin, Viceroy of India, "the Munshi occupies very much the same position as John Brown used to do." Victoria dismissed their complaints as racial prejudice. Abdul Karim remained in her service until he returned to India with a pension on her death.

Victoria's eldest daughter became Empress consort of Germany in 1888, but she was widowed within the year, and Victoria's grandchild Wilhelm became German Emperor as Wilhelm II. Under Wilhelm, Victoria and Albert's hopes of a liberal Germany were not fulfilled. He believed in autocracy. Victoria thought he had "little heart or Zartgefühl [tact] – and ... his conscience & intelligence have been completely wharped [sic]".

Gladstone returned to power aged over 82 after the 1892 general election. Victoria objected when Gladstone proposed appointing the Radical MP Henry Labouchere to the Cabinet, and so Gladstone agreed not to appoint him. In 1894, Gladstone retired and, without consulting the outgoing prime minister, Victoria appointed Lord Rosebery as prime minister. His

government was weak, and the following year Lord Salisbury replaced

him. Salisbury remained prime minister for the remainder of Victoria's

reign.

On 23 September 1896, Victoria surpassed her grandfather George III as the longest reigning monarch in English, Scottish, and British history. The Queen requested that any special celebrations be delayed until 1897, to coincide with her Diamond Jubilee, which was made a festival of the British Empire at the suggestion of Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain.

The prime ministers of all the self governing dominions were invited, and the Queen's Diamond Jubilee procession through London included troops from all over the empire. The parade paused for an open air service of thanksgiving held outside St Paul's Cathedral, throughout which Victoria sat in her open carriage. The celebration was marked by great outpourings of affection for the septuagenarian Queen.

Victoria visited mainland Europe regularly for holidays. In 1889, during a stay in Biarritz, she became the first reigning monarch from Britain to set foot in Spain when she crossed the border for a brief visit. By April 1900, the Boer War was

so unpopular in mainland Europe that her annual trip to France seemed

inadvisable. Instead, the Queen went to Ireland for the first time since

1861, in part to acknowledge the contribution of Irish regiments to the

South African war. In July, her second son Alfred ("Affie")

died; "Oh, God! My poor darling Affie gone too", she wrote in her

journal. "It is a horrible year, nothing but sadness & horrors of

one kind & another."

Following a custom she maintained throughout her widowhood, Victoria spent the Christmas of 1900 at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight. Rheumatism in her legs had rendered her lame, and her eyesight was clouded by cataracts. Through early January, she felt "weak and unwell", and by mid January she was "drowsy ... dazed, [and] confused". She died on Tuesday 22 January 1901 at half past six in the evening, at the age of 81. Her son and successor King Edward VII, and her eldest grandson, Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, were at her deathbed.

In 1897, Victoria had written instructions for her funeral, which was to be military as befitting a soldier's daughter and the head of the army, and white instead of black. On 25 January, Edward VII, the Kaiser and Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught, helped lift her into the coffin. She was dressed in a white dress and her wedding veil. An array of mementos commemorating her extended family, friends and servants were laid in the coffin with her, at her request, by her doctor and dressers. One of Albert's dressing gowns was placed by her side, with a plaster cast of his hand, while a lock of Brown's hair, along with a picture of him, were placed in her left hand concealed from the view of the family by a carefully positioned bunch of flowers. Items of jewellery placed on Victoria included the wedding ring of John Brown's mother, given to her by Brown in 1883. Her funeral was held on Saturday 2 February in St. George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, and after two days of lying - in - state, she was interred beside Prince Albert in Frogmore Mausoleum at Windsor Great Park. As she was laid to rest at the mausoleum, it began to snow.

Victoria is the longest reigning British monarch and the longest reigning Queen regnant in world history; she reigned for a total of 63 years, seven months and two days. She was the last monarch of Britain from the House of Hanover. Her son and heir Edward VII belonged to her husband's House of Saxe - Coburg and Gotha.

According to one of her biographers, Giles St Aubyn, Victoria wrote an average of 2500 words a day during her adult life. From July 1832 until just before her death, she kept a detailed journal, which eventually encompassed 122 volumes. After Victoria's death, her youngest daughter Princess Beatrice, was appointed her literary executor. Beatrice transcribed and edited the diaries covering Victoria's accession onwards, and burned the originals in the process. Despite this destruction, much of the diaries still exist. In addition to Beatrice's edited copy, Lord Esher transcribed the volumes from 1832 to 1861 before Beatrice destroyed them. Part of Victoria's extensive correspondence has been published in volumes edited by A.C. Benson, Hector Bolitho, George Earle Buckle, Lord Esher, Roger Fulford, and Richard Hough among others.

Victoria was physically unprepossessing — she was stout, dowdy and no more than five feet tall — but she succeeded in projecting a grand image. She experienced unpopularity during the first years of her widowhood, but was well liked during the 1880s and 1890s, when she embodied the empire as a benevolent matriarchal figure. Only after the release of her diary and letters did the extent of her political influence become known to the wider public. Biographies of Victoria written before much of the primary material became available, such as Lytton Strachey's Queen Victoria of 1921, are now considered out of date. The biographies written by Elizabeth Longford and Cecil Woodham - Smith, in 1964 and 1972 respectively, are still widely admired. They, and others, conclude that as a person Victoria was emotional, obstinate, honest, and straight - talking.

Through Victoria's reign, the gradual establishment of a modern constitutional monarchy in Britain continued. Reforms of the voting system increased the power of the House of Commons at the expense of the House of Lords and the monarch. In 1867,Walter Bagehot wrote that the monarch only retained "the right to be consulted, the right to encourage, and the right to warn". As

Victoria's monarchy became more symbolic than political, it placed a

strong emphasis on morality and family values, in contrast to the

sexual, financial and personal scandals that had been associated with

previous members of the House of Hanover and which had discredited the

monarchy. The concept of the "family monarchy", with which the

burgeoning middle classes could identify, was solidified.

Victoria's links with Europe's royal families earned her the nickname "the grandmother of Europe". Victoria and Albert had 42 grandchildren, of whom 34 survived to adulthood. Their descendants include Elizabeth II, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, Harald V of Norway, Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden, Margrethe II of Denmark, Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofía of Spain.

One of Victoria's children, her youngest son, Leopold, was affected by the blood clotting disease haemophilia B and two of her five daughters, Alice and Beatrice, were carriers. Royal haemophiliacs descended from Victoria included her great - grandsons, Tsarevich Alexei of Russia, Alfonso, Prince of Asturias, and Infante Gonzalo of Spain. The presence of the disease in Victoria's descendants, but not in her ancestors, led to modern speculation that her true father was not the Duke of Kent but a haemophiliac. There is no documentary evidence of a haemophiliac in connection with Victoria's mother, and as male carriers always suffer the disease, even if such a man had existed he would have been seriously ill. It is more likely that the mutation arose spontaneously because Victoria's father was old at the time of her conception and haemophilia arises more frequently in the children of older fathers. Spontaneous mutations account for about 30% of cases.

Around the world, places and memorials are dedicated to her, especially in the Commonwealth nations. Places named after her, include the capital of the Seychelles, Africa's largest lake, Victoria Falls, the capitals of British Columbia (Victoria) and Saskatchewan (Regina), and two Australian states (Victoria and Queensland).

The Victoria Cross was introduced in 1856 to reward acts of valor during the Crimean War, and it remains the highest British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand award for bravery. Victoria Day is a Canadian statutory holiday and a local public holiday in parts of Scotland celebrated on the last Monday before or on 24 May (Queen Victoria's birthday).

William Ewart Gladstone FRS FSS (29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British Liberal statesman. In a career lasting over sixty years, he served as Prime Minister four separate times (1868 – 1874, 1880 – 1885, February – July 1886 and 1892 – 1894), more than any other person. Gladstone was also Britain's oldest Prime Minister, 84 years old when he resigned for the last time. He had also served as Chancellor of the Exchequer four times (1853 – 1855, 1859 – 1866, 1873 – 1874, and 1880 – 1882).

Gladstone first entered Parliament in 1832. Beginning as a High Tory, Gladstone served in the Cabinet of Sir Robert Peel. After the split of the Conservatives Gladstone was a Peelite – in 1859 the Peelites merged with the Whigs and the Radicals to form the Liberal Party. As Chancellor Gladstone became committed to low public spending and to electoral reform, earning him the sobriquet "The People's William".

Gladstone's first ministry saw many reforms including Disestablishment of the Church of Ireland and the introduction of secret voting. After his electoral defeat in 1874, Gladstone resigned as leader of the Liberal Party, but from 1876 began a comeback based on opposition to Turkey's Bulgarian atrocities. Gladstone's Midlothian Campaign of 1879 – 1880 was an early example of many modern political campaigning techniques. After the1880 election, he formed his second ministry, which saw crises in Egypt (culminating in the death of General Gordon in 1885), and in Ireland, where the government passed repressive measures but also improved the legal rights of Irish tenant farmers. The government also passed the Third Reform Act.

Back in office in early 1886, Gladstone proposed Irish Home rule but this was defeated in the House of Commons in July. The resulting split in the Liberal Party helped keep them out of office, with one short break, for twenty years. In 1892 Gladstone formed his last government at the age of 82. The Second Irish Home Rule Bill passed the Commons but was defeated in the Lords in 1893. Gladstone resigned in March 1894, in opposition to increased naval expenditure. He left Parliament in 1895 and died three years later aged 88.

Gladstone is famous for his oratory, for his rivalry with the Conservative Leader Benjamin Disraeli and his poor relations with Queen Victoria, who once complained, "He always addresses me as if I were a public meeting."

Gladstone

was known affectionately by his supporters as "The People's William" or

the "G.O.M." ("Grand Old Man", or, according to Disraeli, "God's Only

Mistake").

Born in 1809 in Liverpool, England, at 62 Rodney Street, William Ewart Gladstone was the fourth son of the merchant Sir John Gladstone from Leith (now a suburb of Edinburgh), and his second wife, Anne MacKenzie Robertson, from Dingwall, Ross-shire. Gladstone was born and brought up in Liverpool and was of purely Scottish ancestry. One of his earliest childhood memories was being made to stand on a table and say "Ladies and gentlemen" to the assembled audience, probably at a gathering to promote the election of George Canning as MP for Liverpool in 1812.

William Gladstone was educated from 1816 to 1821 at a preparatory school at the vicarage of St Thomas's Church at Seaforth, close to his family's residence, Seaforth House. In 1821 William followed in the footsteps of his older brothers and attended Eton College before matriculating in 1828 at Christ Church, Oxford, where he read Classics and Mathematics, although he had no great interest in mathematics. In December 1831 he achieved the double first class degree he had long desired. Gladstone served as President of the Oxford Union debating society, where he developed a reputation as an orator, which followed him into the House of Commons. At university Gladstone was a Tory and denounced Whig proposals for parliamentary reform.

Following the success of his double first, William traveled with his brother John on a Grand Tour of Europe, visiting Belgium, France, Germany and Italy. On his return to England, William was elected to Parliament in 1832 as Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Newark, partly through the influence of the local patron, the Duke of Newcastle. Although Gladstone entered Lincoln's Inn in 1833, with a view to becoming a barrister, by 1839 he had requested that his name should be removed from the list because he no longer intended to be called to the Bar.

In the House of Commons, Gladstone was initially a disciple of High Toryism, opposing the abolition of slavery and factory legislation. In December 1834 he was appointed as a Junior Lord of the Treasury in Sir Robert Peel's first ministry. The following month he was appointed Under - Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, an office he held until the government's resignation in April 1835.

Gladstone published his first book, The State in its Relations with the Church, in 1838, in which he argued that the goal of the state should be to promote and defend the interests of the Church of England. The following year he married Catherine Glynne, to whom he remained married until his death 59 years later. They had eight children together:

- William Henry Gladstone (1840 – 1891), MP.

- Agnes Gladstone (1842 – 1931), later Mrs. Edward Wickham.

- Rev. Stephen Edward Gladstone (1844 – 1920).

- Catherine Jessy Gladstone (1845 – 1850).

- Mary Gladstone (1847 – 1927), later Mrs. Harry Drew.

- Helen Gladstone (1849 – 1925), Vice - President of Newnham College, Cambridge

- Henry Neville Gladstone (1852 – 1935), Lord Gladstone of Hawarden.

- Herbert John Gladstone (1854 – 1930), MP and Viscount Gladstone.

Gladstone's eldest son William (known as "Willy" to distinguish him from his father) became a Member of Parliament but pre - deceased his father, dying in the early 1890s.

In 1840 Gladstone began to rescue and rehabilitate London prostitutes,

walking the streets of London himself and encouraging the women he

encountered to change their ways. Much to the criticism of his peers, he

continued this practice decades later, even after he was elected Prime Minister.

Gladstone was re-elected in 1841. In September 1842 he lost the forefinger of his left hand in an accident while reloading a gun; thereafter he wore a glove or finger sheath (stall). In the second ministry of Robert Peel he served as President of the Board of Trade (1843 – 44).

Gladstone became concerned with the situation of "coal whippers". These were the men who worked on London docks, "whipping" in baskets from ships to barges or wharves all incoming coal from the sea. They were called up and relieved through public houses and therefore a man could not get this job unless he possessed the favorable opinion of the publican, who looked upon most favorably those who drank. The man's name was written down and the "score" followed. Publicans issued employment solely on the capacity of the man to pay, and men often left the pub to work drunk. They spent their savings on drink to secure the favorable opinion of publicans and therefore further employment. Gladstone passed the Coal Vendors Act 1843 to set up a central office for employment. When this Act expired in 1856 a Select Committee was appointed by the Lords in 1857 to look into the question. Gladstone gave evidence to the Committee: "I approached the subject in the first instance as I think everyone in Parliament of necessity did, with the strongest possible prejudice against the proposal [to interfere]; but the facts stated were of so extraordinary and deplorable a character, that it was impossible to withhold attention from them. Then the question being whether legislative interference was required I was at length induced to look at a remedy of an extraordinary character as the only one I thought applicable to the case... it was a great innovation". Looking back in 1883, Gladstone wrote that "In principle, perhaps my Coalwhippers Act of 1843 was the most Socialistic measure of the last half century".

He resigned in 1845 over the Maynooth Seminary issue,

a matter of conscience for him. In order to improve relations with

Irish Catholics, Peel's government proposed increasing the annual grant

paid to the Seminary for training Catholic priests. Gladstone, who

previously argued in a book that a Protestant country

should not pay money to other churches, supported the increase in the

Maynooth grant and voted for it in Commons, but resigned rather than

face charges that he had compromised his principles to remain in office.

After accepting Gladstone's resignation, Peel confessed to a friend, "I

really have great difficulty sometimes in exactly comprehending what he

means". Gladstone returned to Peel's government as Colonial Secretary in December.

The following year Peel's government fell over the MPs' repeal of the Corn Laws and Gladstone followed his leader into a course of separation from mainstream Conservatives. After Peel's death in 1850 Gladstone emerged as the leader of the Peelites in the House of Commons. He was re-elected for the University of Oxford (i.e., representing the MA graduates of the University) at the General Election in 1847 – Peel had once held this seat but had lost it because of his espousal of Catholic Emancipation in 1829. Gladstone became a constant critic of Lord Palmerston.

As a young man Gladstone had treated his father's estate, Fasque, in the county of Angus, southwest of Aberdeen, as home, but as a younger son he would not inherit it. Instead, from the time of his marriage, he lived at his wife's family's estate, Hawarden, in North Wales. He never actually owned Hawarden, which belonged first to his brother - in - law Sir Stephen Glynne, and was then inherited by Gladstone's eldest son in 1874. During the late 1840s, when he was out of office, he worked extensively to turn Hawarden into a viable business.

In 1848 he also founded the Church Penitentiary Association for the Reclamation of Fallen Women. In May 1849 he began his most active "rescue work" with "fallen women" and met prostitutes late at night on the street, in his house or in their houses, writing their names in a private notebook. He aided the House of Mercy at Clewer near Windsor (which exercised extreme in-house discipline) and spent much time arranging employment for ex-prostitutes. In a 'Declaration' signed on 7 December 1896 and only to be opened after his death by his son Stephen, Gladstone wrote:

With reference to rumors which I believe were at one time afloat, though I know not with what degree of currency: and also with reference to the times when I shall not be here to answer for myself, I desire to record my solemn declaration and assurance, as in the sight of God and before His Judgment Seat, that at no period of my life have I been guilty of the act which is known as that of infidelity to the marriage bed.

In 1927, during a court case over published claims that he had had improper relationships with some of these women, the jury unanimously found that the evidence "completely vindicated the high moral character of the late Mr. W.E. Gladstone".

In 1850 / 51 Gladstone visited Naples for the benefit of his daughter Mary's eyesight. Giacomo

Lacaita, legal adviser to the British embassy, was imprisoned by the

Neapolitan government, as were other political dissidents. Gladstone

became concerned at the political situation in Naples and the arrest and

imprisonment of Neapolitan liberals. In February 1851 the government

allowed Gladstone to visit the prisons where they were held and he

deplored their condition. In April and July he published two Letters to the Earl of Aberdeen against the Neapolitan government and responded to his critics in An Examination of the Official Reply of the Neapolitan Government in 1852. Gladstone's first letter described what he saw in Naples as "the negation of God erected into a system of government". Giustino Fortunato, prime minister of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, knew of the letters from Paolo Ruffo, Neapolitan ambassador in London, but he did not inform the king Ferdinand II. After his unfulfillment, Fortunato was dismissed by the sovereign.

In 1852, following the appointment of Lord Aberdeen as Prime Minister, head of a coalition of Whigs and Peelites, Gladstone became Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Whig Sir Charles Wood and the Tory Disraeli had both been perceived to have failed in the office and so this provided Gladstone with a great political opportunity.

His first budget in 1853 almost completed the work begun by Peel eleven years before in simplifying Britain's tariff of duties and customs. 123 duties were abolished and 133 duties were reduced. The income tax had legally expired but Gladstone proposed to extend it for seven years to fund tariff reductions:

We propose, then, to re-enact it for two years, from April, 1853, to April, 1855, at the rate of 7d. in the £; from April, 1855, to enact it for two more years at 6d. in the £; and then for three years more... from April, 1857, at 5d. Under this proposal, on the 5th of April, 1860, the income - tax will by law expire.

Gladstone wanted to maintain a balance between direct and indirect taxation. He also wished to abolish the income tax. He knew that its abolition depended on a considerable retrenchment in government expenditure. He therefore increased the number of people eligible to pay it by lowering the threshold from £150 to £100. The more people who paid income tax, Gladstone believed, the more the public would pressure the government into abolishing it. Gladstone argued that the £100 line was "the dividing line... between the educated and the laboring part of the community" and that therefore the income tax payers and the electorate were to be the same people, who would then vote to cut government expenditure.

The budget speech (delivered on 18 April), at nearly five hours length, raised Gladstone "at once to the front rank of financiers as of orators". H.C.G. Matthew has written that Gladstone "made finance and figures exciting, and succeeded in constructing budget speeches epic in form and performance, often with lyrical interludes to vary the tension in the Commons as the careful exposition of figures and argument was brought to a climax". The contemporary diarist Charles Greville wrote of Gladstone's speech:

...by universal consent it was one of the grandest displays and most able financial statement that ever was heard in the House of Commons; a great scheme, boldly, skilfully, and honestly devised, disdaining popular clamor and pressure from without, and the execution of it absolute perfection. Even those who do not admire the Budget, or who are injured by it, admit the merit of the performance. It has raised Gladstone to a great political elevation, and, what is of far greater consequence than the measure itself, has given the country assurance of a man equal to great political necessities, and fit to lead parties and direct governments.

However with Britain entering the Crimean War in February 1854, Gladstone introduced his second budget on 6 March. Gladstone had to increase expenditure on the Services and a vote of credit of £1,250,000 was taken to send a 25,000 strong force to the East. The deficit for the year would be £2,840,000 (estimated revenue £56,680,000; estimated expenditure £59,420,000). Gladstone refused to borrow the money needed to rectify this deficit and instead increased the income tax by one half from sevenpence to tenpence - halfpenny in the pound. Gladstone proclaimed that "the expenses of a war are the moral check which it has pleased the Almighty to impose on the ambition and the lust of conquest that are inherent in so many nations". By May £6,870,000 was needed to finance the war and so Gladstone introduced another budget on 8 May. Gladstone raised the income tax from 10 and a half d. to 14d. in order to raise £3,250,000 and spirits, malt, and sugar were taxed in order to raise the rest of the money needed.

He

served until 1855, a few weeks into Lord Palmerston's first

premiership, whereupon he resigned along with the rest of the Peelites

after a motion was passed to appoint a committee of inquiry into the

conduct of the war.

The Conservative Leader Lord Derby became Prime Minister in 1858, but Gladstone – who like the other Peelites was still nominally a Conservative – declined a position in his government, opting not to sacrifice his free trade principles.

Between November 1858 and February 1859, Gladstone, on behalf of Lord Derby's government, was made Extraordinary Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands embarking via Vienna and Trieste on a twelve week mission to the southern Adriatic entrusted with complex challenges that had arisen in connection with the future of the British Protectorate of the Ionian islands.

In

1858, Gladstone took up the hobby of tree felling, mostly of oak trees,

an exercise he continued with enthusiasm until he was 81 in 1891.

Eventually, he became notorious for this activity, prompting Lord Randolph Churchill to

observe 'For the purposes of recreation he has selected the felling of

trees; and we may usefully remark that his amusements, like his

politics, are essentially destructive. Every afternoon the whole world

is invited to assist at the crashing fall of some beech or elm or oak.

The forest laments in order that Mr Gladstone may perspire'. Less

noticed at the time was his practice of replacing the trees he'd felled

with newly planted saplings. Possibly related to this hobby is the fact

that Gladstone was a lifelong bibliophile to

the extent that it has been suggested that in his lifetime, he read

around 20,000 books, and eventually came to own a Library of over

32,000.

In 1859, Lord Palmerston formed a new mixed government with Radicals included, and Gladstone again joined the government as Chancellor of the Exchequer (with most of the other remaining Peelites) to become part of the new Liberal Party.

Gladstone inherited an unpleasant financial situation, with a deficit of nearly five millions and the income tax at 5d. Like Peel, Gladstone dismissed the idea of borrowing to cover the deficit. Gladstone argued that "In time of peace nothing but dire necessity should induce us to borrow". Most of the money needed was acquired through raising the income tax to 9d. Usually not more than two - thirds of a tax imposed could be collected in a financial year so Gladstone therefore imposed the extra four pence at a rate of 8d. during the first half of the year so that he could obtain the additional revenue in one year. Gladstone's dividing line set up in 1853 had been abolished in 1858 but Gladstone revived it, with lower incomes to pay 6 and a half d. instead of 9d. For the first half of the year the lower incomes paid 8d. and the higher incomes paid 13d. in income tax.

On 12 September 1859 the businessman Richard Cobden visited

Gladstone, with Gladstone recording in his diary: "...further conv.

with Mr. Cobden on Tariffs & relations with France. We are closely

& warmly agreed". Cobden was sent as Britain's representative to the negotiations with France's Michel Chevalier for

a free trade treaty between the two countries. Gladstone wrote to

Cobden: "... the great aim — the moral and political significance of the

act, and its probable and desired fruit in binding the two countries

together by interest and affection. Neither you nor I attach for the

moment any superlative value to this Treaty for the sake of the

extension of British trade... What I look to is the social good, the

benefit to the relations of the two countries, and the effect on the

peace of Europe".

Gladstone's budget of 1860 was introduced on 10 February along with the Cobden - Chevalier Treaty between Britain and France that would reduce tariffs between the two countries. This budget "marked the final adoption of the Free Trade principle, that taxation should be levied for Revenue purposes alone, and that every protective, differential, or discriminating duty... should be dislodged". At the beginning of 1859, there were 419 duties in existence. The 1860 budget reduced the number of duties to 48, with 15 duties constituting the majority of the revenue. To finance these reductions in indirect taxation, the income tax, instead of being abolished, was raised to 10d. for incomes above £150 and at 7d. for incomes above £100.

Some of the duties Gladstone intended to abolish in 1860 were the duties on paper, a controversial policy because the duties had traditionally inflated the costs of publishing and thus hindered the dissemination of radical working class ideas. Although Palmerston supported continuation of the duties, using them and income tax revenues to make armament purchases, a majority of his Cabinet supported Gladstone. The Bill to abolish duties on paper narrowly passed Commons but was rejected by the House of Lords. As no money bill had been rejected by Lords for over two hundred years, a furore arose over this vote. The next year, Gladstone included the abolition of paper duties in a consolidated Finance Bill (the first ever) in order to force the Lords to accept it, and accept it they did.

Significantly, Gladstone succeeded in steadily reducing the income tax over the course of his tenure as Chancellor. In 1861 the tax was reduced to ninepence (£0-0s–9d); in 1863 to sevenpence; in 1864 to fivepence; and in 1865 to fourpence. Gladstone believed that government was extravagant and wasteful with taxpayers' money and so sought to let money "fructify in the pockets of the people" by keeping taxation levels down through "peace and retrenchment". Gladstone wrote in 1859 to his brother who was a member of the Financial Reform Association at Liverpool: "Economy is the first and great article (economy such as I understand it) in my financial creed. The controversy between direct and indirect taxation holds a minor, though important place". He wrote to his wife on 14 January 1860: "I am certain, from experience, of the immense advantage of strict account - keeping in early life. It is just like learning the grammar then, which when once learned need not be referred to afterwards".

The Austrian economist, Joseph Schumpeter, described Gladstonian finance in his History of Economic Analysis:

...there was one man who not only united high ability with unparalleled opportunity but also knew how to turn budgets into political triumphs and who stands in history as the greatest English financier of economic liberalism, Gladstone... The greatest feature of Gladstonian finance... was that it expressed with ideal adequacy both the whole civilization and the needs of the time, ex visu of the conditions of the country to which it was to apply; or, to put it slightly differently, that it translated a social, political, and economic vision, which was comprehensive as well as historically correct, into the clauses of a set of co-ordinated fiscal measures... Gladstonian finance was the finance of the system of 'natural liberty,' laissez - faire, and free trade... the most important thing was to remove fiscal obstructions to private activity. And for this, in turn, it was necessary to keep public expenditure low. Retrenchment was the victorious slogan of the day... it means the reduction of the functions of the state to a minimum... retrenchment means rationalization of the remaining functions of the state, which among other things implies as small a military establishment as possible. The resulting economic development would in addition, so it was believed, make social expenditures largely superfluous... Equally important was it... to raise the revenue that would still have to be raised in such a way as to deflect economic behavior as little as possible from what it would have been in the absence of all taxation ('taxation for revenue only'). And since the profit motive and the propensity to save were considered of paramount importance for the economic progress of all classes, this meant in particular that taxation should as little as possible interfere with the net earnings of business... As regards indirect taxes, the principle of least interference was interpreted by Gladstone to mean that taxation should be concentrated on a few important articles, leaving the rest free... Last, but not least, we have the principle of the balanced budget.

Due to his actions as Chancellor, Gladstone earned the reputation as the liberator of British trade and the working man's breakfast table, the man responsible for the emancipation of the popular press from "taxes upon knowledge" and for placing a duty on the succession of the estates of the rich. Gladstone's popularity rested on his taxation policies which meant to his supporters balance, social equity and political justice. The most significant expression of working class opinion was at Northumberland in 1862 when Gladstone visited. George Holyoake recalled in 1865:

When Mr Gladstone visited the North, you well remember when word passed from the newspaper to the workman that it circulated through mines and mills, factories and workshops, and they came out to greet the only British minister who ever gave the English people a right because it was just they should have it... and when he went down the Tyne, all the country heard how twenty miles of banks were lined with people who came to greet him. Men stood in the blaze of chimneys; the roofs of factories were crowded; colliers came up from the mines; women held up their children on the banks that it might be said in after life that they had seen the Chancellor of the People go by. The river was covered like the land. Every man who could ply an oar pulled up to give Mr Gladstone a cheer. When Lord Palmerston went to Bradford the streets were still, and working men imposed silence upon themselves. When Mr Gladstone appeared on the Tyne he heard cheer no other English minister ever heard... the people were grateful to him, and rough pitmen who never approached a public man before, pressed round his carriage by thousands... and thousands of arms were stretched out at once, to shake hands with Mr Gladstone as one of themselves.

When Gladstone first joined Palmerston's government in 1859, he opposed further electoral reform, but he changed his position during Palmerston's last premiership, and by 1865 he was firmly in favor of enfranchising the working classes in towns. This latter policy created friction with Palmerston, who strongly opposed enfranchisement. At the beginning of each session, Gladstone would passionately urge the Cabinet to adopt new policies, while Palmerston would fixedly stare at a paper before him. At a lull in Gladstone's speech, Palmerston would smile, rap the table with his knuckles, and interject pointedly, "Now, my Lords and gentlemen, let us go to business".

As Chancellor, Gladstone made a speech at Newcastle on 7 October 1862 in which he supported the independence of the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War, claiming that Jefferson Davis had "made a nation". Great Britain was officially neutral at the time, and Gladstone later regretted the Newcastle speech. In May 1864 Gladstone said that he saw no reason in principle why all mentally able men could not be enfranchised, but admitted that this would only come about once the working classes themselves showed more interest in the subject. Queen Victoria was not pleased with this statement, and an outraged Palmerston considered it seditious incitement to agitation.

Gladstone's support for electoral reform and disestablishment of the Anglican Church in Ireland had alienated him from his constituents in his Oxford University seat, and he lost it in the 1865 general election. A month later, however, he stood as a candidate in South Lancashire, where he was elected third MP (South Lancashire at this time elected three MPs). Palmerston campaigned for Gladstone in Oxford because he believed that his constituents would keep him "partially muzzled", because many Oxford graduates were Anglican clergymen at that time. A victorious Gladstone told his new constituency, "At last, my friends, I am come among you; and I am come — to use an expression which has become very famous and is not likely to be forgotten — I am come 'unmuzzled'."

On Palmerston's death in October, Earl Russell formed his second ministry. Russell & Gladstone (now the senior Liberal in the House of Commons) attempted to pass a reform bill, which was defeated in the House of Commons because of the refusal of the "Adullamite" Whigs, led by Robert Lowe, to support it. The Conservatives then formed a ministry, in which after long Parliamentary debate Disraeli passed the Second Reform Act of 1867, more far reaching than Gladstone's proposed bill had been.

Lord

Russell retired in 1867 and Gladstone became leader of the Liberal

Party. in 1868 Gladstone proposed the Irish Church Resolutions to

reunite the Liberal Party for government (on the issue of

disestablishment of the Church of Ireland – this would be done during Gladstone's First Government in 1869 and meant that Irish Roman Catholics did not need to pay their tithes to the Anglican Church of Ireland). When these passed the House of Commons Disraeli called a General Election.

In the next general election in 1868, the South Lancashire constituency had been broken up by the Second Reform Act into two: South East Lancashire and South West Lancashire. Gladstone stood for South West Lancashire and for Greenwich, it being quite common then for candidates to stand in two constituencies simultaneously. He was defeated in Lancashire and won in Greenwich. He became Prime Minister for the first time and remained in the office until 1874. Evelyn Ashley famously described the scene in the grounds of Hawarden Castle on 1 December 1868, though getting the date wrong:

One afternoon of November, 1868, in the Park at Hawarden, I was standing by Mr. Gladstone holding his coat on my arm while he, in his shirt sleeves, was wielding an axe to cut down a tree. Up came a telegraph messenger. He took the telegram, opened it and read it, then handed it to me, speaking only two words, namely, ‘Very significant’, and at once resumed his work. The message merely stated that General Grey would arrive that evening from Windsor. This, of course, implied that a mandate was coming from the Queen charging Mr. Gladstone with the formation of his first Government. I said nothing, but waited while the well - directed blows resounded in regular cadence. After a few minutes the blows ceased and Mr. Gladstone, resting on the handle of his axe, looked up, and with deep earnestness in his voice, and great intensity in his face, exclaimed: ‘My mission is to pacify Ireland.’ He then resumed his task, and never said another word till the tree was down.

In the 1860s and 1870s, Gladstonian Liberalism was characterized by a number of policies intended to improve individual liberty and loosen political and economic restraints. First was the minimization of public expenditure on the premise that the economy and society were best helped by allowing people to spend as they saw fit. Secondly, his foreign policy aimed at promoting peace to help reduce expenditures and taxation and enhance trade. Thirdly, laws that prevented people from acting freely to improve themselves were reformed. When an unemployed miner (Daniel Jones) wrote to him to complain of his unemployment and low wages, Gladstone gave what H.C.G. Matthew has called "the classic mid - Victorian reply" on 20 October 1869:

The only means which have been placed in my power of ‘raising the wages of colliers’ has been by endeavoring to beat down all those restrictions upon trade which tend to reduce the price to be obtained for the product of their labor, & to lower as much as may be the taxes on the commodities which they may require for use or for consumption. Beyond this I look to the forethought not yet so widely diffused in this country as in Scotland, & in some foreign lands; & I need not remind you that in order to facilitate its exercise the Government have been empowered by Legislation to become through the Dept. of the P.O. the receivers & guardians of savings.

Gladstone's first premiership instituted reforms in the British Army, Civil Service, and local government to cut restrictions on individual advancement. The Local Government Board Act 1871 put the supervision of the Poor Law under the Local Government Board (headed by G.J. Goschen) and Gladstone's "administration could claim spectacular success in enforcing a dramatic reduction in supposedly sentimental and unsystematic outdoor poor relief, and in making, in co-operation with the Charity Organization Society (1869), the most sustained attempt of the century to impose upon the working classes the Victorian values of providence, self reliance, foresight, and self discipline". Gladstone was associated with the Charity Organization Society's first annual report in 1870. At a speech at Blackheath on 28 October 1871, Gladstone warned his constituents against social reformers:

...they are not your friends, but they are your enemies in fact, though not in intention, who teach you to look to the Legislature for the radical removal of the evils that afflict human life... It is the individual mind and conscience, it is the individual character, on which mainly human happiness or misery depends. (Cheers.) The social problems that confront us are many and formidable. Let the Government labor to its utmost, let the Legislature labor days and nights in your service; but, after the very best has been attained and achieved, the question whether the English father is to be the father of a happy family and the center of a united home is a question which must depend mainly upon himself. (Cheers.) And those who... promise to the dwellers in towns that every one of them shall have a house and garden in free air, with ample space; those who tell you that there shall be markets for selling at wholesale prices retail quantities — I won't say are imposters, because I have no doubt they are sincere; but I will say they are quacks (cheers); they are deluded and beguiled by a spurious philanthropy, and when they ought to give you substantial, even if they are humble and modest boons, they are endeavoring, perhaps without their own consciousness, to delude you with fanaticism, and offering to you a fruit which, when you attempt to taste it, will prove to be but ashes in your mouths. (Cheers.)