<Back to Index>

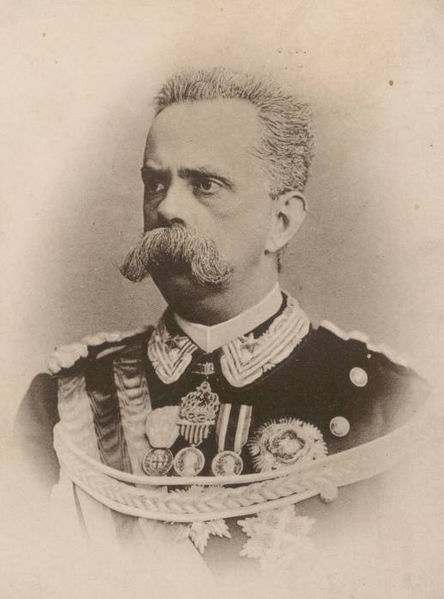

- King of Italy Umberto I, 1844

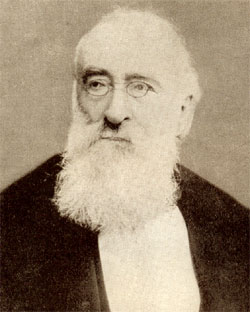

- Prime Minister of Italy Agostino Depretis, 1813

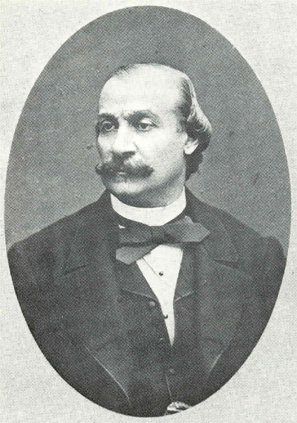

- Minister of Foreign Affairs Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, 1817

- Minister of Foreign Affairs Carlo Felice Nicolis, conte di Robilant, 1826

PAGE SPONSOR

Umberto I or Humbert I (Italian: Umberto Ranieri Carlo Emanuele Giovanni Maria Ferdinando Eugenio di Savoia, English: Humbert Ranier Charles Emmanuel John Mary Ferdinand Eugene of Savoy; 14 March 1844 – 29 July 1900), nicknamed the Good (in Italian il Buono), was the King of Italy from 9 January 1878 until his death. He was deeply loathed in far left circles, especially among anarchists, because of his conservatism and support of the Bava - Beccaris massacre in Milan. He was killed by anarchist Gaetano Bresci two years after the incident.

The son of Victor Emmanuel II and Archduchess Adelaide of Austria, Umberto was born in Turin, which was then capital of the kingdom of Sardinia, on 14 March 1844. His education was entrusted to, amongst others, Massimo Taparelli, marquis d'Azeglio and Pasquale Stanislao Mancini.

From March 1858 he had a military career in the Sardinian army, beginning with the rank of captain. Umberto took part in the Italian Wars of Independence: he was present at the battle of Solferino in 1859, and in 1866 commanded the XVI Division at the Villafranca battle that followed the Italian defeat at Custoza.

Because of the upheaval the Savoys caused to a number of other royal houses (all the Italian ones, and those related closely with them, such as the Bourbons of Spain and France) in 1859 - 60, only a minority of royal families the 1860s were willing to establish relations with the newly founded Italian royal family. It proved difficult to find any royal bride for either of the sons of king Victor Emmanuel II. (His younger son Amedeo, Umberto's brother, married ultimately a Piedmontese subject, princess Vittoria of Cisterna). Their conflict with the papacy did not help these matters. Not many eligible Catholic royal brides were easily available for young Umberto.

At first, Umberto was to marry Archduchess Mathilde of Austria, a scion of a remote sideline of the Austrian imperial house; however, she died as the result of an accident at the age of 18. On 21 April 1868 Umberto married his first cousin, Margherita Teresa Giovanna, Princess of Savoy. Their only son was Victor Emmanuel, prince of Naples. She was one of the rare young ladies of any royal house available to the despised Savoy royal family in that decade - being a Savoy herself.

Ascending the throne on the death of his father (9 January 1878), Umberto adopted the title "Umberto I of Italy" rather than "Umberto IV" (of Savoy), and consented that the remains of his father should be interred at Rome in the Pantheon, rather than the royal mausoleum of Basilica of Superga.

While on a tour of the kingdom, accompanied by Prime Minister Benedetto Cairoli, he was attacked by an anarchist, Giovanni Passanante,

during a parade in Naples on 17 November 1878. The King warded off the

blow with his sabre, but Cairoli, in attempting to defend him, was

severely wounded in the thigh. The would-be assassin was condemned to death, even though the law only allowed the death penalty if the King was killed. The King commuted the sentence to one of penal servitude for

life, which was served in a cell only 1.4 meters high, without

sanitation and with 18 kilograms of chains. Passanante would later die

in a psychiatric institution. The incident upset the health of Queen Margherita for several years.

In foreign policy Umberto I approved the Triple Alliance with Austria - Hungary and Germany, repeatedly visiting Vienna and Berlin. Many in Italy, however, viewed with hostility an alliance with their former Austrian enemies, who were still occupying areas claimed by Italy.

Umberto was also favorably disposed towards the policy of colonial expansion inaugurated in 1885 by the occupation of Massawa in Eritrea. Italy expanded into Somalia in the 1880s as well. Umberto I was suspected of aspiring to a vast empire in north east Africa, a suspicion which tended somewhat to diminish his popularity after the disastrous Battle of Adowa in Ethiopia on 1 March 1896.

In the summer of 1900, Italian forces were part of the Eight Nation Alliance which participated in the Boxer Rebellion in Imperial China. Through the Boxer Protocol, signed after Umberto's death, the Kingdom of Italy gained a concession territory in Tientsin.

Umberto's attitude towards the Holy See was uncompromising. In a 1886 telegram, he declared Rome "untouchable" and affirmed the permanence of the Italian possession of the "Eternal City".'

The reign of Umberto I was a time of social upheaval, though it was later claimed to have been a tranquil belle époque. Social tensions mounted as a consequence of the relatively recent occupation of the kingdom of the two Sicilies, the spread of socialist ideas, public hostility to the colonialist plans of the various governments, especially Crispi's, and the numerous crackdowns on civil liberties. The protesters included the young Benito Mussolini, then a member of the socialist party. On 22 April 1897, Umberto I was attacked again, by an unemployed iron smith, Pietro Acciarito, who tried to stab him near Rome.

During

the colonial wars in Africa, large demonstrations over the rising price

of bread were held in Italy and on 7 May 1898 the city of Milan was put under military control by General Fiorenzo Bava - Beccaris, who ordered the use of cannon on the demonstrators; as a result, about 100 people were killed according to the authorities (some claim the

death toll was about 350); about a thousand were wounded. King Umberto

sent a telegram to congratulate Bava - Beccaris on the restoration of

order and later decorated him with the medal of Great Official of Savoy

Military Order, greatly outraging a large part of the public opinion.

On the evening of 29 July 1900, Umberto was assassinated when he was shot four times by the Italo - American anarchist Gaetano Bresci in Monza. Bresci claimed he wanted to avenge the people killed during the Bava - Beccaris massacre.

Umberto was buried in the Pantheon in Rome, by the side of his father Victor Emmanuel II, on 9 August 1900. He was the last Savoy to be buried there, as his son and successor Victor Emmanuel III died in exile and is still buried in Egypt.

American anarchist Leon Czolgosz claimed that the assassination of Umberto I was his inspiration to kill U.S. President William McKinley in September, 1901.

Agostino Depretis (January 31, 1813 – July 29, 1887) was an Italian statesman.

Depretis was born at Mezzana Corte, near Stradella, in the province of Pavia (Lombardy).

From early manhood a disciple of Giuseppe Mazzini and affiliated with the La Giovine Italia, he took an active part in the Mazzinian conspiracies and was nearly captured by the Austrians while smuggling arms into Milan. Elected deputy in 1848, he joined the Left and founded the journal Il Diritto, but held no official position until appointed governor of Brescia in 1859. In 1860 he went to Sicily on a mission to reconcile the policy of Cavour (who desired the immediate incorporation of the island in the kingdom of Italy) with that of Giuseppe Garibaldi, who wished to postpone the Sicilian plebiscite until after the liberation of Naples and Rome.

Though appointed pro-dictator of Sicily by Garibaldi, he failed in his attempt. Accepting the portfolio of public works in Urbano Rattazzi's cabinet, in 1862, he served as intermediary in arranging with Garibaldi the expedition that ended disastrously at Aspromonte. Four years later, on the outbreak of war against Austria, he entered the Ricasoli cabinet as minister of the navy, and he insisted with admiral Carlo Persano in the attack to the island of Lissa as a revenge for the Italian defeat of Custoza, in this occasion he also refused to give to admiral Persano detailed orders about the expedition in the Adriatic Sea against the fleet led by Wilhelm von Tegetthoff. His apologists contend, however, that, as an inexperienced civilian, he could not have made sudden changes in naval arrangements without disorganizing the fleet, and that in view of the impending hostilities he was obliged to accept the dispositions of his predecessors.

Upon the death of Rattazzi in 1873, Depretis became leader of the Left, prepared the advent of his party to power, and was called upon to form the first cabinet of the Left in 1876. Prior to this, Depretis "was a journalist - politician who had allied himself in parliament with the Left. When he came into power it was as the leader of the Left, and as such he ruled as prime minister, save for a brief interlude, for most of the eleven years from 1876 to 1887." Overthrown by Benedetto Cairoli in March 1878 on the grist tax question, he succeeded, in the following December, in defeating Cairoli, became again premier, but on July 3, 1879 was once more overturned by Cairoli. In November 1879 he, however, entered the Cairoli cabinet as minister of the interior, and in May 1881 succeeded to the premiership, retaining that office until his death.

During the long interval he recomposed his cabinet four times, first throwing out Giuseppe Zanardelli and Alfredo Baccarini in order to please the Right, and subsequently bestowing portfolios upon Cesare Ricotti - Magnani, Robilant and other Conservatives, so as to complete the political process known as trasformismo. A few weeks before his death he repented of his transformist policy, and again included Francesco Crispi and Zanardelli in his cabinet.

During his long term of office he abolished the grist tax, extended suffrage, completed the railway system, aided Mancini in forming the Triple Alliance, and initiated colonial policy by the occupation of Massawa; but, at the same time, he vastly increased indirect taxation, corrupted and destroyed the fiber of parliamentary parties, and, by extravagance in public works, impaired the stability of Italian finance.

Depretis (a Freemason, incidentally) and Conte di Cavour, Italy's first prime minister, are the only Italian prime ministers who died in office.

Pasquale Stanislao Mancini (March 17, 1817 - December 26, 1888) was an Italian jurist and statesman.

Mancini was born in Castel Baronia, in the province of Avellino. He became well established in intellectual circles in Naples, editing and publishing a number of newspapers and journals, and gained a reputation in law after the 1841 publication of his correspondence with Terenzio Mamiani on the right to punish. He did not attend university, but rather was educated privately, and was granted a law degree in 1844 by a special exemption. He married poet Laura Beatrice Mancini in 1840, and she ran a literary salon for liberal minded Neapolitans out of their house.

In 1848 he was instrumental in persuading Ferdinand II to participate in the war against Austria. Twice he declined the offer of a portfolio in the Neapolitan cabinet, and upon the triumph of the reactionary party undertook the defense of the Liberal political prisoners.

Threatened with imprisonment in his turn, he fled to Piedmont, where he obtained a professorship at the University of Turin and became preceptor of the crown prince Humbert. In 1860 he prepared the legislative unification of Italy, opposed the idea of an alliance between Piedmont and Naples, and, after the fall of the Bourbons, was sent to Naples as administrator of justice, in which capacity he suppressed the religious orders, revoked the Concordat, proclaimed the right of the state to Church property, and unified civil and commercial jurisprudence.

In 1862 he became minister of public instruction in the Rattazzi cabinet, and induced the Chamber to abolish capital punishment. Thereafter, for fourteen years, he devoted himself chiefly to questions of international law and arbitration, but in 1876, upon the advent of the Left to power, became minister of justice in the Depretis cabinet. His Liberalism found expression in the extension of press freedom, the repeal of imprisonment for debt, and the abolition of ecclesiastical tithes.

During the Conclave of 1878 he succeeded, by negotiations with Cardinal Pecci (afterwards Leo XIII), in inducing the Sacred College to remain in Rome, and, after the election of the new pope, arranged for his temporary absence from the Vatican for the purpose of settling private business. Resigning office in March 1878, he resumed the practice of law, and secured the annulment of Garibaldi's marriage. The fall of Cairoli led to Mancini's appointment (1881) to the ministry of foreign affairs in the Depretis administration. The growing desire in Italy for alliance with Austria and Germany did not at first secure his approval; nevertheless he accompanied King Humbert to Vienna and conducted the negotiations which led to the informal acceptance of the Triple Alliance.

His desire to retain French confidence was the chief motive of his refusal in July 1882 to share in the British expedition to Egypt, but, finding his efforts fruitless when the existence of the Triple Alliance came to be known, he veered to the English interest and obtained assent in London to the Italian expedition to Massawa. An indiscreet announcement of the limitations of the Triple Alliance contributed to his fall in June 1885, when he was succeeded by Count di Robilant.

He died in Rome in the December 1888.

Carlo Felice Nicolis, conte di Robilant (1826 – October 17, 1888), Italian statesman and diplomat, was a native of Turin.

He entered the army, and lost his left hand at Novara, where he was aide - de - camp to Charles Albert, king of Piedmont. He fought in 1859, and reached the rank of general in the Austrian campaign of 1866, after which he served on the delimitation commission. He was chief of the Military Academy, and in 1867 was made prefect of Ravenna to suppress political disorder. He was defeated at Turin in the elections for the Chamber in in 1870, and was sent in 1871 as minister plenipotentiary to Vienna, where he subsequently became ambassador.

He was connected with the Prussian nobility through his mother, he married an Austrian, a daughter of Prince Edmund Clary - Aldringen. In spite of the active part he had taken in driving Austria from Italy, he was a persona grata in Vienna, and his policy was steadily directed to an alliance between the two powers. This was accomplished by the secret terms of the Triple Alliance in 1882. He was recalled to Rome in 1885 to become minister for foreign affairs in the Depretis cabinet.

Robilant's independent attitude as foreign minister secured greater consideration for Italy from her allies, but he did not adapt himself to the exigencies of domestic politics, and his excessive unpopularity contributed to the downfall of the ministry on February 7, 1887, consequent on an adverse vote on the Massawa question.

Before leaving office, he completed the negotiations for the renewal of the Triple Alliance, and for its extension to cover Anglo - Italian co-operation in the Mediterranean. In the new Depretis - Crispi administration Robilant was not included. He was sent to London as ambassador in the next year, but died two months after his arrival.