<Back to Index>

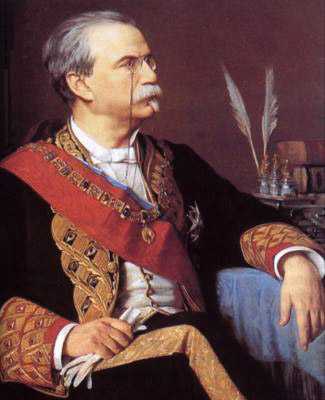

- King of Spain Alfonso XII, 1857

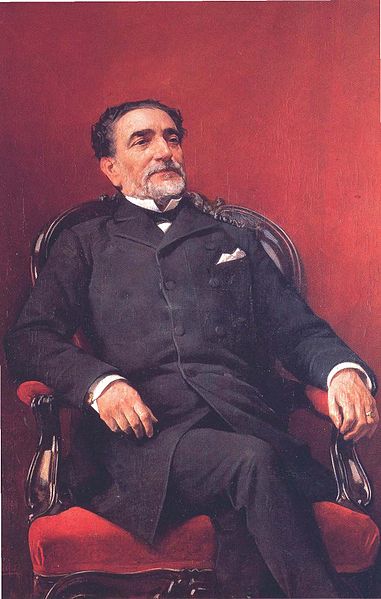

- Prime Minister of Spain Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, 1828

- Minister of State Práxedes Mariano Mateo Sagasta y Escolar, 1825

PAGE SPONSOR

Alfonso XII (born Alfonso Francisco de Asís Fernando Pío Juan María de la Concepción Gregorio Pelayo) (Madrid, 28 November 1857 – El Pardo, 25 November 1885) was King of Spain, reigning from 1874 to 1885, after a coup d'état restored the monarchy and ended the ephemeral First Spanish Republic.

Alfonso was the son of Queen Isabella II of Spain, and allegedly, of her husband and King Consort, Francis, Duke of Cádiz. Alfonso's biological paternity is uncertain: there is speculation that his biological father may have been Enrique Puig y Moltó (a captain of the guard), or even an American dental student. These rumors were used as political propaganda against Alfonso by the Carlists.

When Queen Isabella and her husband were forced to leave Spain by the Revolution of 1868, Alfonso accompanied them to Paris. From there, he was sent to the Theresianum at Vienna to continue his studies. On 25 June 1870, he was recalled to Paris, where his mother abdicated in his favor, in the presence of a number of Spanish nobles who had tied their fortunes to that of the exiled queen. He assumed the title of Alfonso XII, for although no King of united Spain had borne the name "Alfonso XI", the Spanish monarchy was regarded as continuous with the more ancient monarchy represented by the 11 kings of Asturias, León and Castile also named Alfonso.

Shortly afterwards, Alfonso proceeded to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in the United Kingdom in

order to continue his military studies. While there, he issued, on 1

December 1874, in reply to a birthday greeting from his followers, a

manifesto proclaiming himself the sole representative of the Spanish

monarchy. At the end of that year, when Marshal Serrano left Madrid to take command of the northern army in the Carlist War, Brigadier Martínez Campos, who had long been working more or less openly for the king, led some battalions of the central army to Sagunto, rallied to his own flag the troops sent against him, and entered Valencia in

the king's name. Thereupon the president of the council resigned, and

his power was transferred to the king's plenipotentiary and adviser, Antonio Cánovas.

Within a few days after Canovas del Castillo took power, the new king, proclaimed on 29 December 1874, arrived at Madrid, passing through Barcelona and Valencia and was acclaimed everywhere (1875). In 1876, a vigorous campaign against the Carlists, in which the young king took part, resulted in the defeat of Don Carlos and the Duke's abandonment of the struggle.

On 23 January 1878 at the Basilica of Atocha in Madrid, Alfonso married his cousin, Princess Maria de las Mercedes, daughter of Antoine, Duke of Montpensier, but she died within six months of the marriage.

Towards the end of 1878 a young workman of Tarragona, Juan Oliva Moncasi, fired at the king in Madrid.

On 29 November 1879 at the Basilica of Atocha in Madrid, Alfonso married a much more distant relative, Maria Christina of Austria, daughter of Archduke Karl Ferdinand of Austria and of his wife Archduchess Elisabeth of Austria. During the honeymoon, a pastry cook named Otero fired at the young sovereign and his wife as they were driving in Madrid.

The children of this marriage were:

- María de las Mercedes, Princess of Asturias, (11 September 1880 – 17 October 1904), married on 14 February 1901 to Prince Carlos of Bourbon - Two Sicilies, and titular heiress from the death of her father until the posthumous birth of her brother

- María Teresa, (12 November 1882 – 23 September 1912), married to Prince Ferdinand of Bavaria on 12 January 1906

- Alfonso XIII (17 May 1886 – 28 February 1941). Born posthumously. He married Princess Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg

In

1881 Alfonso refused to sanction a law by which the ministers were to

remain in office for a fixed term of 18 months. Upon the consequent

resignation of Canovas del Castillo, he summoned Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, the Liberal leader, to form a new cabinet.

In November 1885, Alfonso died, just short of his 28th birthday, at the Royal Palace of El Pardo. He had been suffering from tuberculosis, but the immediate cause of his death was a recurrence of dysentery.

Coming to the throne at such an early age, Alfonso had served no apprenticeship in the art of ruling, but he possessed great natural tact and a sound judgment ripened by the trials of exile. Benevolent and sympathetic in disposition, he won the affection of his people by fearlessly visiting districts ravaged by cholera or devastated by earthquake in 1885. His capacity for dealing with men was considerable, and he never allowed himself to become the instrument of any particular party. During his short reign, peace was established both at home and abroad, finances were well regulated, and the various administrative services were placed on a basis that afterwards enabled Spain to pass through the disastrous war with the United States without the threat of a revolution.

He was the 996th Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Spain, the 104th Grand Cross of the Order of the Tower and Sword in 1861 and the 775th Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1881.

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo (February 8, 1828 – August 8, 1897) was a Spanish politician and historian known principally for his role in supporting the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy to the Spanish throne and for his death at the hands of an anarchist assassin, Michele Angiolillo.

Born in Málaga as the son of Antonio Cánovas García and Juana del Castillo y Estébanez, Cánovas moved to Madrid after the death of his father where he lived with his mother's cousin, the writer Serafín Estébanez Calderón. Although he studied law at the University of Madrid, he showed an early interest in politics and Spanish history. His active involvement in politics dates to the 1854 revolution led by the general Leopoldo O'Donell, when he wrote the Manifesto of Manzanares that accompanied the military overthrow of the sitting government, laid out the political goals of the movement, and played a critical role as it attracted the masses' support when the coup seemed to fail. During the final years of Isabel II, he served in a number of posts, including a diplomatic mission to Rome, governor of Cádiz, and director general of local administration. This period of his political career culminated in his being twice made a government minister, first taking the interior portfolio in 1864 and then the overseas territories portfolio in 1865 - 1866. After the 1868 Glorious Revolution (Revolución Gloriosa), he retired from the government, although he was a strong supporter of the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy during the First Spanish Republic (1873 – 1874) and as the leader of the conservative minority in the Cortes, he declaimed against universal suffrage and freedom of religion. He also wrote the Manifesto of Sandhurst and ordered Alfonso XII to publish it just as he, some years ago, had done with O'Donnell.

Cánovas returned to active politics with the 1874 overthrow of the Republic by General Martínez Campos and the elevation of Isabell II's son Alfonso XII to the throne. He served as Prime Minister (Primer presidente del Consejo de Ministros) for six years starting in 1874 (although he was twice briefly replaced in 1875 and 1879). During this period, he was a principal author of the Spanish Constitution of 1876, a document which formalized the constitutional monarchy that had resulted from the restoration of Alfonso and limited suffrage in order to reduce the political influence of the working class and assuage the voting support from the wealthy minority becoming the protected Status Quo. Cánovas Del Castillo played a key role in bringing an end to the last Carlist threat to Bourbon authority (1876) by merging a group of dissident Carlist deputies with his own Conservative party. An artificial two party system designed to reconcile the competing militarist, Catholic and Carlist power bases led to an alternating prime ministership with the progressive Práxedes Mateo Sagasta after 1881. He also assumed the functions of the Head of State during the regency of María Cristina following Alfonso's death in 1885.

By the late 1880s, Cánovas's policies were under threat from two sources. First, his overseas policy was increasingly untenable. A policy of repression against Cuban nationalists was ultimately ineffective and Spain's authority was challenged most seriously by the 1895 rebellion led by José Martí. Spain's policy against Cuban independence brought her increasingly into conflict with the United States, an antagonism that culminated in the Spanish - American War of 1898. Second, the political repression of Spain's working class was growing increasingly troublesome, and pressure for expanded suffrage mounted amid widespread discontent with the cacique system of electoral manipulation.

Cánovas policies included mass arrests and a policy of torture:

At the same time, Cánovas remained an active man of letters. His historical writings earned him a considerable reputation, particularly his History of the Decline of Spain (Historia de la decadencia de España), for which he was elected at the young age of 32 to the Real Academia de la Historia in 1860. This was followed by elevation to other bodies of letters, including the Real Academia Española in 1867, the Academia de Ciencias Morales y Políticas in 1871 and the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in 1887. He also served as the head of the Athenaeum in Madrid (1870 – 74, 1882 – 84 and 1888 – 89).During a religious procession in 1896, at Barcelona, a bomb was thrown. Immediately three hundred men and women were arrested. Some were Anarchists, but the majority were trade unionists and Socialists. They were thrown into that terrible bastille, Montjuich, and subjected to most horrible tortures. After a number had been killed, or had gone insane, their cases were taken up by the liberal press of Europe, resulting in the release of a few survivors.

The man primarily responsible for this revival of the Inquisition was Canovas del Castillo, Prime Minister of Spain. It was he who ordered the torturing of the victims, their flesh burned, their bones crushed, their tongues cut out. Practiced in the art of brutality during his regime in Cuba, Canovas remained absolutely deaf to the appeals and protests of the awakened civilized conscience.

Cánovas eventually paid a personal price for his policies of repression. In 1897, he was shot dead by Michele Angiolillo, an Italian anarchist, at the spa Santa Águeda, in Mondragón, Guipúzcoa. He thus did not live to see Spain's loss of her final colonies to the United States after the Spanish - American War.

The policies of repression and political manipulation that Cánovas made a cornerstone of his government helped foster the nationalist movements in both Catalonia and the Basque provinces and set the stage for labor unrest during the first two decades of the twentieth century. The disastrous colonial policy not only led to the loss of Spain's remaining colonial possessions in the Pacific and Caribbean, it also seriously weakened the government at home. A failed post - war coup by Camilo García de Polavieja set off a long period of political instability that ultimately led to the collapse of the monarchy and the dissolution of the constitution that Cánovas had authored.

His white marble mausoleum was carved by Agustí Querol Subirats at the Panteón de Hombres Ilustres in Madrid.

Práxedes Mariano Mateo Sagasta y Escolar (July 21, 1825 – January 5, 1903) was a Spanish politician who served as Prime Minister on eight occasions between 1870 and 1902 — always in charge of the Liberal Party — as part of the turno pacifico, alternating with the Liberal - Conservative leader Antonio Cánovas. A Freemason, he was known for possessing an excellent oratorical talent.

Sagasta was born on July 21, 1825 at Torrecilla en Cameros, Logroño, La Rioja, Spain. Being a member of the Progressive Party while a student at the Engineering School of Madrid in 1848, Sagasta was the only one in the school who refused to sign a letter supporting Queen Isabel II. After his studies, he assumed an active role in government.

Sagasta served in the Spanish Cortes between 1854 - 1857 and 1858 - 1863. In 1866 he exiled himself to France after a failed coup, returning to Spain in 1868 to take part in the provisional government which was created after the 1868 Spanish Revolution.

As Prime Minister of Spain during the Spanish - American War of 1898 (during which time Spain lost its remaining colonies), Sagasta agreed to an autonomous constitution for both Cuba and Puerto Rico. Sagasta's political opponents saw his action as a betrayal of Spain and blamed him for the country's defeat in the war and the loss of its island territories after the Treaty of Paris of 1898. Nevertheless he continued to be active in politics for another four years. Sagasta died on January 5, 1903 in Madrid.