<Back to Index>

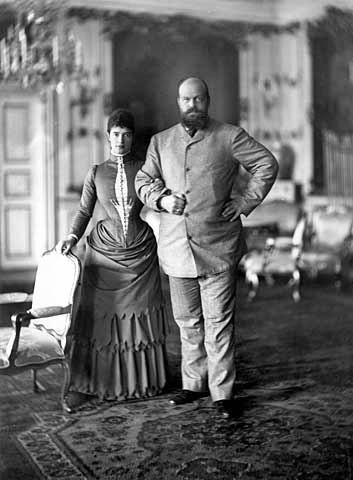

- Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias Alexander III, 1845

- Minister of Foreign Affairs Adam Jerzy Czartoryski, 1770

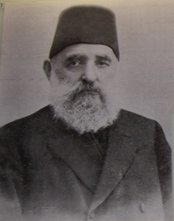

- Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Abdul Hamid II, 1842

- Grand Vizier Mehmed Said Pasha, 1830

- Grand Vizier Kamil Pasha, 1833

PAGE SPONSOR

Alexander Alexandrovich (Russian: Александр Александрович) (1845 – 1894), historically remembered as Alexander III or Alexander the Peacemaker reigned as Emperor of Russia from 13 March [O.S. 1 March] 1881 until his death on 1 November [O.S. 20 October] 1894.

Alexander Alexandrovich Romanov was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia, the second son of czar Alexander II by his wife Princess Marie of Hesse and by Rhine.

In disposition, Alexander bore little resemblance to his soft hearted, liberal father, and still less to his refined, philosophic, sentimental, chivalrous, yet cunning granduncle Alexander I, who coveted the title of "the first gentleman of Europe". Although an enthusiastic amateur musician and patron of the ballet, he was seen as lacking refinement and elegance. Indeed, he rather relished the idea of being of the same rough texture as the great majority of his subjects. His straightforward, abrupt manner savored sometimes of gruffness, while his direct, unadorned method of expressing himself harmonized well with his rough hewn, immobile features and somewhat sluggish movements. His education was not such as to soften these peculiarities. More than six feet tall (about 1.9 m), he was also noted for his immense physical strength, though the large sebaceous cyst on the left side of his nose caused him to be severely mocked by his contemporaries. He always sat for photographs and portraits with the right side of his face most prominent.

Perhaps an account from the memoirs of the artist Alexander Benois best describes an impression of Alexander III:

After a performance of the ballet 'Tsar Kandavl' at the Mariinsky Theater, I first caught sight of the Emperor. I was struck by the size of the man, and although cumbersome and heavy, he was still a mighty figure. There was indeed something of the muzhik [Russian peasant] about him. The look of his bright eyes made quite an impression on me. As he passed where I was standing, he raised his head for a second, and to this day I can remember what I felt as our eyes met. It was a look as cold as steel, in which there was something threatening, even frightening, and it struck me like a blow. The Tsar's gaze! The look of a man who stood above all others, but who carried a monstrous burden and who every minute had to fear for his life and the lives of those closest to him. In later years I came into contact with the Emperor on several occasions, and I felt not the slightest bit timid. In more ordinary cases Tsar Alexander III could be at once kind, simple, and even almost homely.

Though he was destined to be one of the great counter - reforming Tsars, Alexander had little prospect of succeeding to the throne during the first two decades of his life, as he had an elder brother, Nicholas, who seemed of robust constitution. Even when this elder brother first displayed symptoms of delicate health, the notion that he might die young was never seriously taken, and he was betrothed to the Princess Dagmar of Denmark.

Under these circumstances, the greatest solicitude was devoted to the education of Nicholas as Tsarevich, whereas Alexander received only the perfunctory and inadequate training of an ordinary Grand Duke of that period. This did not go much beyond secondary instruction, and included practical acquaintance with French, English and German, and a certain amount of military drill.

Alexander became heir apparent (as Tsarevich) with Nicholas' sudden death in 1865. It was then that he began to study the principles of law and administration under Konstantin Pobedonostsev, then a professor of civil law at Moscow State University and later (from 1880) chief procurator of the Holy Synod. Pobedonostsev awakened in his pupil very little love of abstract studies or prolonged intellectual exertion, but he did influence the character of Alexander's reign by instilling into the young man's mind the belief that zeal for Russian Orthodox thought was an essential factor of Russian patriotism and that this was to be specially cultivated by every right - minded Tsar. During those years when he was heir apparent — 1865 to 1881 — Alexander did not play a prominent part in public affairs, but he allowed it to become known that he had certain ideas of his own which did not coincide with the principles of the existing government.

On his deathbed, Alexander's elder brother Nicholas is said to have expressed the wish that his fiancée, Princess Dagmar of Denmark, should marry his successor. This wish was swiftly realized, when on 9 November [O.S. 28 October] 1866 in the Imperial Chapel of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, Alexander wed Dagmar, who converted to Russian Orthodoxy and took the name Maria Feodorovna. The union proved a most happy one and remained unclouded to the end. Unlike his father, there was no adultery in his marriage.

On 13 March 1881, Alexander's father, Tsar Alexander II, was assassinated by members of the terrorist organization Narodnaya Volya. As a result, he ascended to the Russian imperial throne (in Nennal 13. 03. 1881). He and Maria Feodorovna were officially crowned Tsar and Tsarina on 27 May 1883.

On the day of his assassination, Alexander II had signed an ukaz creating

a number of consultative commissions that acted as advisory bodies to

the monarch. Upon ascending to the throne, however, Alexander III took

Pobedonostsev's advice and canceled the policy before it was published.

He made clear that the power of the autocracy would not be limited or weakened in any way.

All of Alexander III's internal reforms were intended to reverse the liberalization of society that had occurred under his father's reign. He believed that the country was to be saved from revolutionary agitation by remaining true to Russian Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality, the ideology introduced by his grandfather, Tsar Nicholas I. Alexander's political ideal was a nation composed a single nationality, language, and religion, as well as one form of administration. He attempted to realize this ideal by the institution of mandatory teaching of the Russian language throughout the Empire, including to his German, Polish, and other non - Russian subjects (with the exception of the Finns); the patronization of Eastern Orthodoxy through the destruction of the remnants of German, Polish, and Swedish institutions in the respective provinces; and by the weakening of Judaism via the persecution of the Jews. The latter policy was implemented in the "May Laws" of 1882, which banned Jews from inhabiting rural areas and shtetls (even within the Pale of Settlement) and restricted the occupations in which they could engage.

Alexander weakened the power of the zemstvo, an elective local administrative division resembling the American county and the English parish council, and placed the autonomous administration of the peasant communes under the supervision of land owning proprietors appointed by his government. These "land captains", as they were called, were feared and resented throughout the Empire's peasant communities. These acts weakened the nobility and the peasantry and brought Imperial administration under the Emperor's personal control.

Encouraged

by its successful assassination of Alexander II, Narodnaya Volya began

planning the murder of Alexander III. The plot was uncovered by the Okhrana and five of the conspirators – including Alexander Ulyanov, the older brother of Vladimir Lenin – were captured and hanged on 20 May [O.S. 8 May] 1887. On 29 October [O.S. 17 October] 1888 the Imperial train was derailed at Borki.

At the moment of the crash, the royal family was in the dining car. Its

roof collapsed, and Alexander held its remains on his shoulders as the

children fled outdoors. The onset of Alexander's kidney failure was

later attributed to the blunt trauma suffered in this incident.

In foreign affairs Alexander was emphatically a man of peace, but not at all a partisan of the doctrine of peace at any price, and he adhered to the principle that the best means of averting war is to be well prepared for it. Though he was indignant at the conduct of German chancellor Otto von Bismarck towards Russia, he avoided an open rupture with Germany and even revived the League of Three Emperors for a time.

It was only in the last years of his reign, when Mikhail Katkov had acquired a certain influence over him, that Alexander adopted a more hostile attitude towards Berlin, and even then he confined himself to keeping a large number of troops near the German frontier and establishing cordial relations with France. With regard to Bulgaria he exercised similar self control. The efforts of Prince Alexander and afterwards of Stambolov to destroy Russian influence in the principality excited his indignation, but he persistently vetoed all proposals to intervene by force of arms.

In Central Asian affairs he followed the traditional policy of gradually extending Russian domination without provoking a conflict with the United Kingdom (Panjdeh Incident), and he never allowed the bellicose partisans of a forward policy to get out of hand. As a whole his reign cannot be regarded as one of the eventful periods of Russian history; but it must be admitted that under his hard, unsympathetic rule the country made considerable progress. Emperor Alexander and his Danish born wife regularly spent their summers in their Langinkoski manor near Kotka on the Finnish coast, where their children were immersed in a Scandinavian lifestyle of relative modesty.

He deprecated what he considered undue foreign influence in general, and German influence in particular, so the adoption of genuine national principles was off in all spheres of official activity, with a view to realizing his ideal of a homogeneous Russia — homogeneous in language, administration and religion. With such ideas and aspirations he could hardly remain permanently in cordial agreement with his father, who, though a good patriot according to his lights, had strong German sympathies, often used the German language in his private relations, occasionally ridiculed the exaggerations and eccentricities of the Slavophiles and based his foreign policy on the Prussian alliance.

The antagonism first appeared publicly during the Franco - Prussian War, when the Tsar supported the cabinet of Berlin and the Tsarevich did not conceal his sympathies for the French. It reappeared in an intermittent fashion during the years 1875 – 1879, when the Eastern question produced so much excitement in all ranks of Russian Society. At first the Tsarevich was more Slavophile than the government, but his phlegmatic nature preserved him from many of the exaggerations indulged in by others, and any of the prevalent popular illusions he may have imbibed were soon dispelled by personal observation in Bulgaria, where he commanded the left wing of the invading army.

Never

consulted on political questions, he confined himself to his military

duties and fulfilled them in a conscientious and unobtrusive manner.

After many mistakes and disappointments, the army reached Constantinople and the Treaty of San Stefano was signed, but much that had been obtained by that important document had to be sacrificed at the Congress of Berlin. Bismarck failed

to do what was confidently expected of him by the Russian Tsar. In

return for the Russian support, which had enabled him to create the German Empire, it

was thought that he would help Russia to solve the Eastern question in

accordance with her own interests, but to the surprise and indignation

of the cabinet of Saint Petersburg he confined himself to acting the

part of "honest broker" at the Congress, and shortly afterwards he

ostentatiously contracted an alliance with Austria for the express purpose of counteracting Russian designs in Eastern Europe.

The Tsarevich could point to these results as confirming the views he

had expressed during the Franco - Prussian War, and he drew from them the

practical conclusion that for Russia the best thing to do was to recover

as quickly as possible from her temporary exhaustion and to prepare for

future contingencies by a radical scheme of military and naval

reorganization. In accordance with this conviction, he suggested that

certain reforms should be introduced.

Alexander III became ill with nephritis in 1894, and died of this disease at the Livadia Palace on 1 November [O.S. 20 October] 1894. His remains were interred at the Peter and Paul Fortress in Saint Petersburg. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Nicholas, as Nicholas II.

An equestrian statue of Alexander III sculpted by Paolo Troubetzkoy once graced Znamenskaya Square in front of the Moscow Rail Terminal in St. Petersburg. It was later moved to the inner courtyard of the Marble Palace. Another memorial is located in the city of Irkutsk at the Angara embankment.

Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski (Lithuanian: Аdomas Jurgis Čartoriskis, Russian: Адам Ежи Чарторыйский; also known as Adam George Czartoryski in English; January 14, 1770 – July 15, 1861) was a Polish - Lithuanian noble, statesman and author. He was the son of Prince Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski and Izabela Fleming.

Czartoryski became Minister of Foreign Affairs of Imperial Russia and was rumored to have been a lover of Louise of Baden, Empress consort to Alexander I of Russia.

Czartoryski

held the distinction of having been part, at different times, of the

governments of two mutually hostile countries. He was de facto Chairman of the Russian Council of Ministers (1804 – 6), and President of the Polish National Government during the November 1830 Uprising against Imperial Russia.

Czartoryski was born on January 14, 1770 in Warsaw. He was the son of Prince Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski and Izabela Fleming. It was rumored that Adam was the fruit of a liaison between Izabela and Russian ambassador to Poland, Nikolai Repnin. However, Repnin left the country two years before Adam Czartoryski was born. After careful education at home by eminent specialists, mostly French, he went abroad in 1786. At Gotha, Czartoryski heard Johann Wolfgang von Goethe read his Iphigeneia in Tauris and made the acquaintance of the dignified Johann Gottfried Herder and "fat little Christoph Martin Wieland."

In 1789 Czartoryski visited Great Britain with his mother and was present at the trial of Warren Hastings. On a second visit in 1793 he made many acquaintances among the British aristocracy and studied the British constitution.

In the interval between these visits, he fought for his country during the war of the second partition and would subsequently also have served under Tadeusz Kościuszko, had he not been arrested on his way to Poland at Brussels by the Austrian government in the service of Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor.

After the third partition of Poland the Czartoryski estates were

confiscated, and in May 1795 Adam and his younger brother Constantine

were summoned to Saint Petersburg.

Later in 1795, the two brothers were commanded to enter the Russian service, Adam becoming an officer in the horse, and Constantine in the foot guards. Catherine the Great was so favorably impressed by the youths that she restored them part of their estates, and in early 1796 made them gentlemen - in - waiting.

Adam had already met Grand Duke Alexander at a ball at Princess Golitsyna's, and the youths at once conceived a strong "intellectual friendship" for each other. On the accession of Tsar Paul I, Czartoryski was appointed adjutant to Alexander, now Tsarevich, and was permitted to revisit his Polish estates for three months.

At this time the tone of the Russian court was extremely liberal. Humanitarian enthusiasts like Pyotr Volkonsky and Nikolay Novosiltsev possessed great influence.

Throughout the reign of Paul I, Czartoryski was in high favor and on terms of the closest intimacy with the Tsar, who in December 1798 appointed him ambassador to the court of Charles Emmanuel IV of Sardinia. On reaching Italy, Czartoryski found that that monarch was a king without a kingdom, so that the outcome of his first diplomatic mission was a pleasant tour through Italy to Naples, the acquisition of the Italian language, and a careful exploration of the antiquities of Rome.

In the spring of 1801 the new tsar, Alexander I,

summoned his friend back to Saint Petersburg. Czartoryski found the

Tsar still suffering from remorse at his father's assassination, and

incapable of doing anything but talk religion and politics to a small

circle of friends. To all remonstrances, he only replied, "There's

plenty of time." The Senate did most of the current business; Pyotr Vasilyevich Zavadovsky, a pupil of the Jesuits, was minister of education.

Tsar Alexander appointed Czartoryski curator of the Vilna Academy (April 3, 1803) so that he might give full play to his advanced ideas. Czartoryski was, however, unable to devote much attention to education, for from the beginning of 1804, as foreign affairs adjunct, he had exercised practical control of Russian diplomacy. His first act had been to protest energetically the murder of Louis - Antoine - Henri de Bourbon - Condé (March 20, 1804) and insist on an immediate rupture with the government of the French Revolution, then under First Consul Napoléon Bonaparte.

On June 7, 1804, the French minister, Gabriel Marie Joseph, comte d'Hédouville, left St. Petersburg; and on August 11 a note dictated by Czartoryski to Alexander was sent to the Russian minister in London, urging the formation of an anti - French coalition. It was also Czartoryski who framed the Convention of November 6, 1804, whereby Russia agreed to put 115,000, and Austria 235,000, men in the field against Napoleon.

Finally, in April 1805 he signed an offensive - defensive alliance with George III's United Kingdom.

But

Czartoryski's most striking ministerial act was a memorial written in

1805, otherwise undated, which aimed at transforming the whole map of

Europe: Austria and Prussia were to divide Germany between them. Russia was to acquire the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus with Constantinople, and Corfu. Austria was to have Bosnia, Wallachia and Ragusa. Montenegro, enlarged by Mostar and the Ionian Islands,

was to form a separate state. The United Kingdom and Russia together

were to maintain the equilibrium of the world. In return for their

acquisitions in Germany, Austria and Prussia were to consent to the

creation of an autonomous Polish state extending from Danzig (Gdańsk) to the sources of the Vistula,

under the protection of Russia. This plan presented the best guarantee,

at the time, for the independent existence of Poland. But in the

meantime Austria had come to an understanding with England about

subsidies, and war had begun.

In 1805 Czartoryski accompanied Alexander to Berlin and to Olmütz (Olomouc, Moravia) as chief minister. He regarded the Berlin visit a blunder, chiefly due to his distrust of Prussia; but Alexander ignored his representations, and in February 1807 Czartoryski lost favor and was superseded by Andrei Budberg.

But, though no longer a minister, Czartoryski continued to enjoy Alexander's confidence in private, and in 1810 the Tsar candidly admitted to Czartoryski that his policy in 1805 had been erroneous and he had not made a proper use of his opportunities.

That

same year, Czartoryski left Saint Petersburg forever; but the personal

relations between him and Alexander were never better. The friends met

again at Kalisz (Greater Poland)

shortly before the signing of the Russo - Prussian alliance on February

20, 1813, and Czartoryski was in the Tsar's suite at Paris in 1814, and

rendered him material services at the Congress of Vienna.

Everyone thought that Czartoryski, who more than any other man had prepared the way for the Congress Kingdom, and had designed the Constitution of the Kingdom of Poland, would be its first namiestnik, or viceroy, but he was content with the title of senator - palatine and a share in the administration.

In 1817 he married Anna Sapieżanka. The wedding led to a duel with his rival, Ludwik Pac.

On his father's death in 1823, Czartoryski retired to his ancestral castle at Puławy;

but the November 1830 Uprising brought him back to public life. As

president of the provisional government, he summoned (December 18, 1830)

the Sejm of 1831, and, after the end of Chlopicki's dictatorship, was elected chief of the supreme council (Polish National Government) by 121 out of 138 votes (January 30, 1831).

On September 6, 1831, his disapproval of the popular excesses at Warsaw caused him to resign from the government after having sacrificed half his fortune to the national cause. Throughout the Uprising, he did not live up to his great reputation.

Yet the sexagenarian statesman showed great energy. On August 23, 1831, he joined Italian General Girolamo Ramorino's army corps as a volunteer, and subsequently formed a confederation of the three southern provinces of Kalisz, Sandomierz and Kraków. At war's end, when the Uprising was crushed by the Russians, he was sentenced to death, though the sentence was soon commuted to exile.

On February 25, 1832, in the United Kingdom, he founded a Literary Association of the Friends of Poland.

Czartoryski emigrated to France, where he resided in Paris' Hôtel Lambert — a prominent Polish émigre political figure, head of a political faction accordingly called the Hôtel Lambert.

Polonezköy (Adampol) was founded by Prince Adam Czartoryski in 1842. He was the Chairman of the Polish National Uprising Government and the leader of a political emigration party. The settlement was named Adam - koj (Adamköy) after its founder, which means the "Village of Adam" in Turkish (Adampol means "Town of Adam" in Polish). Polonezköy or Adampol is a small village at the Asian side of Istanbul, about 30 kilometers away from the historic city center. Adam Czartoryski wanted to create the second emigration center here (the first one was in Paris, France.) He sent his representative, Michał Czajkowski, to Turkey. Michał Czajkowski, after converting to Islam in 1850, became known as Mehmed Sadyk Pasza (Mehmet Sadık Paşa). He purchased the forest area which encompasses present day Adampol from a missionary order of Lazarists. Plans were made to establish Adampol on this area in the future.

At the beginning, the village was inhabited by 12 people, but there were no more than 220 people when the village was most populated. In the course of time, Adampol developed and was flooded by a lot of emigrants from the unsuccessful rebellions of November 1848, the Crimean War in 1853, and by runaways from Siberia and from captivity in Circassia. The first inhabitants busied themselves with agriculture, raising and forestry.

He died at his country residence at Montfermeil, near Meaux, on July 15, 1861. He left two sons, Witold (1824 – 65) and Władysław Czartoryski (1828 – 94), and a daughter Izabela, who in 1857 married Jan Działyński.

Between the November and January Uprisings, in 1832 – 61, Czartoryski supported the idea of resurrecting an updated Polish - Lithuanian Commonwealth on federation principles.

The visionary statesman and former friend, confidant and de facto foreign minister of Russia's Tsar Alexander I acted as the "uncrowned king and unacknowledged foreign minister" of a nonexistent Poland.

He had been disappointed in the hopes that he had reposed, as late as the Congress of Vienna, in Alexander's willingness to undertake reforms, and the distillation of some years' subsequent study and thought was Czartoryski's book, completed in 1827 but published only in 1830, Essai sur la diplomatie (Essay on Diplomacy). This book is, according to the historian Marian Kamil Dziewanowski, indispensable to an understanding of the Prince's many activities conducted in France's capital following the ill fated Polish November 1830 Uprising. Czartoryski wanted to find a place for Poland in the Europe of the time. He sought to interest western Europeans in the adversities of a stateless nation that was nevertheless an indispensable part of the European structure.

Pursuant to the Polish motto, "For our freedom and yours", Czartoryski connected Polish efforts for independence with similar movements of other subjugated nations in Europe and in the East as far as the Caucasus. Thanks to his private initiative and generosity, the émigrés of a subjugated nation conducted a foreign policy often on a broader scale than had the old independent Polish - Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Of particular interest are Czartoryski's observations, in the Essay on Diplomacy, regarding Russia's role in the world. He wrote that, "Having extended her sway south and west, and being by the nature of things unreachable from the east and north, Russia becomes a source of constant threat to Europe." He argued that it would have been in Russia's interest, instead, to have surrounded herself with "friend[s rather than] slave[s]." Czartoryski also identified a future threat from Prussia and urged the incorporation of East Prussia into a resurrected Poland.

Above all, however, he aspired to reconstitute – with French, British and Turkish support – a Polish - Lithuanian Commonwealth federated with the Czechs, Slovaks, Hungarians, Romanians and all the South Slavs of the future Yugoslavia. Poland, in his concept, could have mediated the conflicts between Hungary and the Slavs, and between Hungary and Romania.

Czartoryski's plan seemed achievable during

the period of national revolutions in 1848 – 49 but foundered on lack of

western support, on Hungarian intransigence toward the Czechs, Slovaks

and Romanians, and on the rise of German nationalism." "Nevertheless", concludes Dziewanowski, "the Prince's endeavor constitutes a [vital] link [between] the 16th century Jagiellon [federative prototype] and Józef Piłsudski's federative - Prometheist program [that was to follow after World War I]."

His Imperial Majesty, The Sultan Abdülhamid II, Emperor of the Ottomans, Caliph of the Faithful (also known as Abdul Hamid II or Abd Al-Hamid II Khan Ghazi) (Ottoman Turkish: عبد الحميد ثانی `Abdü’l-Ḥamīd-i sânî, Turkish: İkinci Abdülhamit) (21 / 22 September 1842 – 10 February 1918) was the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire. He was the last Sultan to exert effective control over the Ottoman Empire. He oversaw a period of decline in the power and extent of the Empire, ruling from 31 August 1876 until he was deposed on 27 April 1909. He was succeeded by Mehmed V. His deposition following the Young Turk Revolution was hailed by most Ottoman citizens, who welcomed the return to constitutional rule.

Abdülhamid II was born in Topkapı Palace in Istanbul (formerly Constantinople). He was the son of Sultan Abdülmecid I and one of his many wives, the Valide Sultan Tirimüjgan, 16 August 1819 – Constantinople, Feriye Palace, 3 October 1852), originally named Virjin.He later also became the adoptive son of another of his father's wives, Valide Sultan Rahime Perestu. He was a skilled carpenter and personally crafted most of his own furniture, which can be seen today at the Yıldız Palace and Beylerbeyi Palace in Istanbul. Abdülhamid II was also interested in opera and personally wrote the first ever Turkish translations of many opera classics. He also composed several opera pieces for the Mızıka-ı Hümayun which he established, and hosted the famous performers of Europe at the Opera House of Yıldız Palace which was recently restored and featured in the film Harem Suare (1999) of the Turkish - Italian director Ferzan Özpetek, which begins with the scene of Abdülhamid II watching a performance. Unlike many other Ottoman sultans, Abdülhamid II traveled to distant countries. Nine years before he took the throne, he accompanied his uncle Sultan Abdülaziz on his visit to Austria, France and England in 1867.

He succeeded to the throne following the deposition of his brother Murad on 31 August 1876. He himself was deposed in favor of his brother Mehmed in 1909. His brother had no real powers and continued as a figurehead only. At his accession, some commentators were impressed by the fact that he rode practically unattended to the Eyüp Sultan Mosque where he was given the Sword of Osman. Most people expected Abdülhamid II to have liberal ideas, and some conservatives were inclined to regard him with suspicion as a dangerous reformer.

He took over default in the public funds, and an empty treasury.

He was made the 1,058th Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Spain in 1880 and the 202nd Grand Cross of the Portuguese Order of the Tower and Sword in 1882.

He did not plan and express any goal in his accession speech, however he worked with the Young Ottomans to realize some form of constitutional arrangements. This new form in its theoretical expression could help to realize a liberal transition with Islamic features, which could balance the Tanzimat's imitation of western norms. The political structure of western norms did not work with the centuries old Ottoman political culture, even if the pressure from the Western world was enormous to adapt western ways of political administration. On 23 December 1876, under the shadow of the 1875 insurrection in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the war with Serbia and Montenegro and the feeling aroused throughout Europe by the cruelty used in stamping out the Bulgarian rebellion, he declared the constitution and its parliament.

The international Constantinople Conference which met at Istanbul (Constantinople) towards the end of 1876 was surprised by the promulgation of a constitution, but European powers at the conference rejected the constitution as a significant change; they preferred the 1856 constitution, the Hatt-ı Hümayun and 1839 Hatt-ı Şerif of Gülhane, but questioned whether there was need for a parliament to act as an official voice of the people.

In

any event, like many other would be reforms of the Ottoman Empire

change proved to be nearly impossible. Russia continued to mobilize for

war. However, everything changed when the British fleet approached the

capital from the Sea of Marmara. The Sultan suspended (but did not abolish) the constitution and Midhat Pasha, its author, was exiled soon afterwards. Early in 1877 the Ottoman Empire went to war with the Russian Empire.

Abdul Hamid's biggest fear, near dissolution, was coming to effect by the Russian declaration of war on 24 April 1877 and following Russian victory by February 1878. Abdul Hamid did not find any help. The chancellor Prince Gorchakov had effectively purchased Austrian neutrality with the Reichstadt Agreement, and the British Empire, though still fearing the Russian threat to British dominance in Southern Asia, did not involve itself in the conflict because of public opinion following the reports of Ottoman brutality in putting down the Bulgarian uprising. The Treaty of San Stefano, a treaty between Russia and the Ottoman Empire signed at the end of the war, imposed harsh terms: the Ottoman Empire gave independence to Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro; granted autonomy to Bulgaria; instituted reforms in Bosnia and Herzegovina; and ceded the Dobruja and parts of Armenia to Russia, which would also be paid an enormous indemnity.

As Russia could dominate the newly independent states, her influence in Southeastern Europe was greatly increased by the Treaty of San Stefano. Due to the insistence of the Great Powers (especially the United Kingdom), the treaty was later revised at the Congress of Berlin so as to reduce the great advantages acquired by Russia. In exchange of these favors, Cyprus was "rented" to Britain in 1878 while the British forces occupied Egypt and Sudan in 1882 with the pretext of "bringing order" to those provinces. Cyprus, Egypt and Sudan remained as Ottoman provinces "on paper" until 1914, when Britain officially annexed those territories in response to the Ottoman participation in World War I at the side of the Central Powers.

- There was also trouble in Egypt, where a discredited khedive had to be deposed. Abdülhamid mishandled relations with Urabi Pasha, and as a result Great Britain gained virtual control over Egypt by sending its troops with the pretext of "bringing order".

- There were problems on the Greek frontier and in Montenegro, where the European powers were determined that the decisions of the Berlin Congress should be carried into effect.

- The union in 1885 of Bulgaria with Eastern Rumelia was another blow. The creation of an independent and powerful Bulgaria was viewed as a serious threat to the Ottoman Empire. For many years Abdülhamid had to deal with Bulgaria in a way that did not antagonize either Russian or German wishes.

Crete was granted extended privileges, but these did not satisfy the population, which sought unification with Greece.

In early 1897 a Greek expedition sailed to Crete to overthrow Ottoman

rule in the island. This act was followed by war, in which the Ottoman

Empire defeated Greece (Greco - Turkish War (1897)). But a few months later Crete was taken over en depot by England, France, and Russia. Prince George of Greece was appointed as ruler and Crete was also lost to the Ottoman Empire.

The Triple Entente – that is, the United Kingdom, France and Russia – maintained strained relations with the Ottoman Empire. Abdülhamid and his close advisors believed the empire should be treated as an equal player by these great powers. In the Sultan's view, the Ottoman Empire was a European empire, distinct for having more Muslims than Christians. Abdülhamid and his divan viewed themselves as modern. However, their actions were often construed by Europeans as exotic or uncivilized.

Abdülhamid now viewed the new German Empire as a possible friend of the empire. Kaiser Wilhelm II was twice hosted by Abdülhamid in Istanbul; first on 21 October 1889, and nine years later, on 5 October 1898 (Wilhelm II later visited Istanbul for a third time, on 15 October 1917, as a guest of Mehmed V). German officers (like Baron von der Goltz and von Ditfurth) were employed to oversee the reorganization of the Ottoman army.

German government officials were brought in to reorganize the Ottoman government's finances. Abdülhamid tried to take more of the reins of power into his own hands, for he distrusted his ministers. Germany's friendship was not disinterested, and had to be fostered with railway and loan concessions. In 1899 a significant German desire, the construction of a Berlin - Baghdad railway, was granted.

Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany also requested the Sultan's help when having trouble with Muslims. During the Boxer Rebellion, the Chinese Muslim Kansu Braves fought against the German Army repeatedly, routing them along with the other 8 nation alliance forces at the First intervention, Seymour Expedition, China 1900. It was only on the second attempt in the Gasalee Expedition that the Alliance managed to get through to battle the Chinese Muslim troops at the Battle of Peking. Kaiser Wilhelm was so alarmed by the Chinese Muslim troops that he requested the Caliph Abdul Hamid II of the Ottoman Empire to

find a way to stop the Muslim troops from fighting. Abdul Hamid II

agreed to the Kaiser's demands and sent Enver Pasha to China in 1901,

but the rebellion was over by that time.

The national humiliation of the situation in Macedonia, together with the resentment in the army against the palace spies and informers, at last brought matters to a crisis.

In the summer of 1908 the Young Turk revolution broke out and Abdülhamid, upon learning that the troops in Salonica were marching on Istanbul (23 July), at once capitulated. On the 24th an irade announced the restoration of the suspended constitution of 1876; the next day, further irades abolished espionage and censorship, and ordered the release of political prisoners.

On

17 December, Abdülhamid opened the Turkish parliament with a

speech from the throne in which he said that the first parliament had

been "temporarily dissolved until the education of the people had been

brought to a sufficiently high level by the extension of instruction

throughout the empire."

The new attitude of the sultan did not save him from the suspicion of intriguing with the powerful reactionary elements in the state, a suspicion confirmed by his attitude towards the counter revolution of 13 April 1909 known as 31 Mart Vakası, when an insurrection of the soldiers backed by a conservative public upheaval in the capital overthrew the cabinet. The government, restored by soldiers from Salonica, decided on Abdülhamid's deposition, and on 27 April his brother Reshad Efendi was proclaimed as Sultan Mehmed V.

The

Sultan's counter coup, which had appealed to conservative Islamists in

the context of the Young Turks' liberal reforms, resulted in the

massacre of tens of thousands of Christian Armenians in the Adana

province.

Most people expected Abdülhamid II to have liberal ideas, and some conservatives were inclined to regard him with suspicion as a dangerous reformer. In the event, like many other would be reformers of the Ottoman Empire, change proved to be nearly impossible. Default in the public funds, an empty treasury, the 1875 insurrection in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the war with Serbia and Montenegro and the feeling aroused throughout Europe by the cruelty used in stamping out the Bulgarian rebellion all proved good reasons not to undertake any significant changes.

There were many setbacks:

- Financial embarrassments forced him to consent to a foreign control over the national debt. In a decree issued in December 1881, a large portion of the empire's revenues were handed over to the Public Debt Administration for the benefit of (mostly foreign) bondholders.

Over the years Abdülhamid succeeded in reducing his ministers to the position of secretaries, and he concentrated much of the administration of the Empire into his own hands at Yıldız Palace. But internal dissension was not reduced. Crete was constantly in turmoil. The Greeks living within the Ottoman Empire's borders were dissatisfied, as were the Armenians.

His

distrust for the reformist admirals of the Ottoman navy (whom he

suspected of plotting against him and trying to bring back the 1876

constitution) and his subsequent decision to lock the Ottoman fleet

(which ranked as the 3rd largest fleet in the world during the reign of

his predecessor Abdülaziz) inside the Golden Horn caused the loss of Ottoman overseas territories and islands in North Africa, the Mediterranean Sea and the Aegean Sea during and after his reign.

Abdülhamid recognized that the ideas Tanzimat could not bring the disparate peoples of the empire to common identity, such as Ottomanism. Russia's pan - Slavism, pan - Hellennism, was stronger than Ottomanism, in the Ottoman Empire. Abdülhamid tried to hold on formulation of a new and more relevant ideological principle. Ottoman sultans beginning with 1517 were also Caliphs. He wanted to put forward that fact, so he emphasized the Ottoman Caliphate.

Abdülhamid always resisted the pressure of the European powers to the last moment, in order to seem to yield only to overwhelming force, while posing as the champion of Islam against aggressive Christendom. Panislamic propaganda was encouraged; the privileges of foreigners in the Ottoman Empire, which were often seen as an obstacle to government, were curtailed. Along with the strategically important Istanbul - Baghdad Railway, the Istanbul - Medina Railway was also completed - making the trip to Hajj more efficient - though there was still a 160 mile (260 km) camel ride to get to Mecca. Emissaries were sent to distant countries preaching Islam and the Caliph's supremacy. During his rule, Abdülhamid refused Theodor Herzl's offers to pay down a substantial portion of the Ottoman debt in exchange for a charter allowing the Zionists access to Palestine.

Abdülhamid's

appeals to Muslim sentiment were powerless against widespread

disaffection within his Empire due to perennial misgovernment. In Mesopotamia and Yemen disturbance

was endemic; nearer home, a semblance of loyalty was maintained in the

army and among the Muslim population only by a system of delation and

espionage, and by wholesale arrests. After his rule began,

Abdülhamid became obsessed with the paranoia of being assassinated

and withdrew himself into the fortified seclusion of the Yıldız Palace.

Starting around 1890 the Armenians began demanding the implementation of the

reforms which were promised to them at the Berlin conference. Unrest

occurred in 1892 and 1893 at Merzifon and Tokat. Armenian groups staged

protests and were met by violence. Sultan Abdülhamid did not

hesitate to put down these revolts with harsh methods, possibly to show

the unshakable power of the monarch, and often used the local Muslims

(in most cases the Kurds) against the Armenians. According to Turkish scholar Taner Akçam, Kaiser Wilhelm II of

Germany claimed that eighty thousand Armenians had been killed, and

French reports claimed that two hundred thousand had been killed. In 1907, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation attempted to assassinate him

with a car bombing during a public appearance, but the Sultan delayed

for a minute and the bomb went off early, killing 26, wounding 58 (of

which 4 died at hospital) and demolishing 17 cars in the process.

Surviving the assassination, he pardoned the assassin.

The ex-sultan was conveyed into dignified captivity at Salonica. In 1912, when Salonica fell to Greece, he was returned to captivity in Constantinople. He spent his last days studying, carpentering and writing his memoirs in custody at Beylerbeyi Palace in the Bosphorus, where he died on 10 February 1918, just a few months before his brother, the Sultan. He was buried in Constantinople. Abdülhamid was the last relatively authoritative Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. He presided over thirty three years of decline. The Ottoman Empire had long been acknowledged as the Sick Man of Europe by its enemies, the British, French and most European countries excluding Germany, Bulgaria and Austria - Hungary.

Abdülhamid

commissioned thousands of photographs of his empire. Fearful of

assassination, he did not travel often (though still more than many

previous rulers) and photographs provided visual evidence of what was

taking place in his realm. The Sultan presented

large gift albums of photographs to various governments and heads of

state, including the United States (William Allen, "The Abdul Hamid II

Collection," History of Photography eight (1984): 119–45.) and Great

Britain (M.I. Waley and British Library, "Sultan Abdulhamid II Early

Turkish Photographs in 51 Albums from the British Library on Microfiche"

(Zug, Switzerland, 1987). The American collection is housed in the Library of Congress and has been digitized.

Abdülhamid II was born at Çırağan Palace, Ortaköy, or at Topkapı Palace, both in Constantinople, the son of Sultan Abdülmecid I and one of his many wives, Tîr-î-Müjgan Sultan, (Yerevan, 16 August 1819 – Constantinople, Feriye Palace, 2 November 1853), originally named Virjin, an Armenian, but some says she was a Circassian. He later also became the adoptive son of another of his father's wives, Valide Sultan Rahime Perestu. He was a skilled carpenter and personally crafted most of his own furniture, which can be seen today at the Yıldız Palace and Beylerbeyi Palace in Constantinople. Abdülhamid II was also interested in opera and personally wrote the first ever Turkish translations of many opera classics. He also composed several opera pieces for the Mızıka-ı Hümayun which he established, and hosted the famous performers of Europe at the Opera House of Yıldız Palace which was recently restored and featured in the film Harem Suare (1999) of the Turkish - Italian director Ferzan Özpetek, which begins with the scene of Abdülhamid II watching a performance.

In the opinion of F. A. K. Yasamee:

He was a striking amalgam of determination and timidity, of insight and fantasy, held together by immense practical caution and an instinct for the fundamentals of power. He was frequently underestimated. Judged on his record, he was a formidable domestic politician and an effective diplomat.

He was also a good wrestler of Yağlı güreş and

a 'patron saint' of the wrestlers. He organized wrestling tournaments

in the empire and selected wrestlers were invited to the palace.

Abdülhamid personally tried the sportsmen and good ones remained in

the palace.

Abdülhamid was also a poet just like many other Ottoman sultans. One of the sultan's poems translates thus:

My Lord I know you are the Dear One (Al-Aziz)... And no one but you are the Dear One

My God be my helper in this critical hour

You are the One, and nothing else

My God take my hand in these hard times

He was extremely fond of Sherlock Holmes novels.

Mehmed Said Pasha (Modern Turkish: Küçük Mehmet Sait Paşa, literally the lesser Mehmed Said Pasha; 1830 - 1914) was an Ottoman statesman and editor of the Turkish newspaper Jerid - i - Havadis.

He became first secretary to Sultan Abdul Hamid II shortly after the Sultan's accession, and is said to have contributed to the realizations of his majesty's design of concentrating power in his own hands; later he became successively minister of the interior and then governor of Bursa, reaching the high post of grand vizier in 1879. He was grand vizier seven more times under Abdul Hamid, and once under his successor, Mehmed V Reşat. He was known for his opposition to the extension of foreign influence in Turkey.

In 1896 he took refuge at the British embassy at Istanbul,

and, though then assured of his personal liberty and safety, remained

practically a prisoner in his own house. He came into temporary

prominence again during the revolution of 1908. On 22 July he succeeded Fuat Pasha as grand vizier, but on the 6 August was replaced by the more liberal Kamil Pasha, at the insistence of the young Turkish committee. During the Italian crisis in 1911 - 12 he was again called to the grand - viziership.

Kâmil Pasha (Turkish: Kıbrıslı Mehmet Kamil Paşa , literally Mehmed Kamil Pasha the Cypriot"), also spelled as Kiamil Pasha was an Ottoman statesman of Turkish Cypriot origin in the late 19th century and early 20th century, who became, as aside regional or international posts within the Ottoman state structure, grand vizier of the Empire during four different periods.

He was born in Nicosia in 1833, son of Captain Salih Ağa from the village of Gaziler, in Northern Cyprus. His first post was in the household of the Khedive of Egypt who at that time was only nominally dependent to the central Ottoman power in İstanbul. In the course of this appointment he visited London for the Great Exhibition of 1851 in charge of one of the Khedive's sons. Kiamil's sojourn in England left in him a lifelong admiration for Britain and during his career within the Ottoman state, he was always known to be an Anglophile.

Having full command of English, thenceforth to the close of his career he zealously sought the friendship of England for Turkey.

After remaining in Egypt for ten years, Mehmed Kamil exchanged the service of Abbas I for that of the Ottoman Government as of 1860 and for the ensuing nineteen years - that is to say until he first entered the Cabinet - he filled very numerous administrative appointments in every part of the Empire. He governed, or helped to govern provinces such as Eastern Rumelia, Hercegovina, Kosovo and his native Cyprus.

Between 1885 and 1913 he filled the office of Grand Vizier four times. His periods of office were;

- from 25 September 1885 to 4 September 1891, under Abdülhamid II's reign,

- from 2 October 1895 to 7 November 1895, under Abdülhamid II's reign,

- from 5 August 1908 to 14 February 1909, under Abdülhamid II's reign and during the Second Constitutional Era in the Ottoman Empire,

- and from 29 October 1912 to 23 January 1913, under Mehmed V Reşad's reign and during the Second Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire.

In May 1913, he returned to his native Cyprus which he had not seen since he had ceased to govern it as far back as 1864.

The reason was no happy one. After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, Kamil initially had tried to compromise with the new men in power. But soon he decided to oppose the Young Turk Regime and became a figurehead of the so-called "liberal" (merely conservative - traditionalist) opposition. After the overthrow of the Young Turk Regime in summer 1912, he became Grand - Vizier of the then ruling liberals. But he had no time to consolidate power because the Ottoman Empire got involved in the First Balkan War of 1912 / 13 and suffered serious military defeat, accompanied by massacres and mass flight of Muslim inhabitants of the contested Balkan provinces. In January 1913, Kamil's government decided to accept severe peace conditions including massive territorial losses. The Young Turks in the military forces used that period of ultimate weakness and governmental unpopularity for their second coup d'état.

On 23 January 1913, Enver Pasha, one of the Young Turk military leaders, burst with some of his associates into the Sublime Porte while the Cabinet was actually in session. One of Envers officers, Yakup Cemil, shot the Minister of War Nazım Pasha and the group pressed Kamil Paşa to resign immediately.

Kamil was put under house arrest and surveillance. The ex-Grand Vizier (who probably was in danger of life) was invited by his British friend Lord Kitchener to stay with him in Cairo. After three months in Egypt, Mehmed Kamil Pasha decided to wait a favorable turn of fortune in his native Cyprus.

Five weeks after his return to Cyprus the assassination of his Young Turk successor in the Grand Vizierate, Mahmud Şevket Pasha, occurred in June 1913, possibly to avenge the murder of Nazım Pasha. The Young Turk regime reacted with persecution of well known opoosition politicians. The prominent Old Turks were either expelled or had to flee from Turkey. Ahmed Djemal Paşa, then Young Turk prefect of the capital Constantinople, indicated to Kamil's family that he had to leave the Ottoman Empire or he would be arrested. His family joined his exile.

On 14 November 1913, while full of plans for revisiting England in 1914, Mehmed Kamil Paşa suddenly died of syncope and was buried in the court of Arab Ahmed Pasha Mosque.

Sir Ronald Storrs, British Governor of Cyprus from 1926 to 1932, caused a memorial to be raised over Mehmed Kamil Pasha's grave. He also composed the English inscription, carved on the headstone below a Turkish one in old lettering. It runs as follows:

His Highness Kiamil Pasha

Son of Captain Salih Agha of Pyroi

Born in Nicosia in 1833

Treasury Clerk

Commissioner of Larnaca

Director of Evqaf

Four times Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire

A Great Turk and

A Great Man.