<Back to Index>

- Element 43 Technetium Tc, 1936

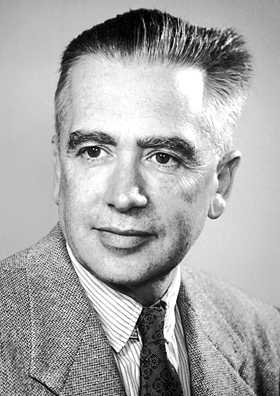

- Mineralogist Carlo Perrier, 1886

- Physicist Emilio Gino Segrè, 1905

PAGE SPONSOR

Technetium is the chemical element with atomic number 43 and symbol Tc. It is the lowest atomic number element without any stable isotopes; every form of it is radioactive. Nearly all technetium is produced synthetically and only minute amounts are found in nature. Naturally occurring technetium occurs as a spontaneous fission product in uranium ore or by neutron capture in molybdenum ores. The chemical properties of this silvery gray, crystalline transition metal are intermediate between rhenium and manganese.

Many of technetium's properties were predicted by Dmitri Mendeleev before the element was discovered. Mendeleev noted a gap in his periodic table and gave the undiscovered element the provisional name ekamanganese (Em). In 1937 technetium (specifically the technetium-97 isotope) became the first predominantly artificial element to be produced, hence its name (from the Greek τεχνητός, meaning "artificial").

Its short lived gamma ray - emitting nuclear isomer — technetium - 99m — is used in nuclear medicine for a wide variety of diagnostic tests. Technetium - 99 is used as a gamma ray - free source of beta particles. Long lived technetium isotopes produced commercially are by-products of fission of uranium - 235 in nuclear reactors and are extracted from nuclear fuel rods. Because no isotope of technetium has a half-life longer than 4.2 million years (technetium - 98), its detection in red giants in 1952, which are billions of years old, helped bolster the theory that stars can produce heavier elements.

From the 1860s through 1871, early forms of the periodic table proposed by Dimitri Mendeleev contained a gap between molybdenum (element 42) and ruthenium (element 44). In 1871, Mendeleev predicted this missing element would occupy the empty place below manganese and therefore have similar chemical properties. Mendeleev gave it the provisional name ekamanganese (from eka-, the Sanskrit word for one), because the predicted element was one place down from the known element manganese.

Many early researchers, both before and after the periodic table was published, were eager to be the first to discover and name the missing element; its location in the table suggested that it should be easier to find than other undiscovered elements. It was first thought to have been found in platinum ores in 1828 and was given the name polinium, but turned out to be impure iridium. Then, in 1846, the element ilmenium was claimed to have been discovered, but later was determined to be impure niobium. This mistake was repeated in 1847 with the "discovery" of pelopium.

In 1877, the Russian chemist Serge Kern reported discovering the missing element in platinum ore. Kern named what he thought was the new element davyum (after the noted English chemist Sir Humphry Davy), but it was eventually determined to be a mixture of iridium, rhodium and iron. Another candidate, lucium, followed in 1896, but it was determined to be yttrium. Then in 1908, the Japanese chemist Masataka Ogawa found evidence in the mineral thorianite, which he thought indicated the presence of element 43. Ogawa named the element nipponium, after Japan (which is Nippon in Japanese). In 2004, H.K Yoshihara used "a record of X-ray spectrum of Ogawa's nipponium sample from thorianite [which] was contained in a photographic plate preserved by his family. The spectrum was read and indicated the absence of the element 43 and the presence of the element 75 (rhenium)."

German chemists Walter Noddack, Otto Berg, and Ida Tacke reported the discovery of element 75 and element 43 in 1925, and named element 43 masurium (after Masuria in eastern Prussia, now in Poland, the region where Walter Noddack's family originated). The group bombarded columbite with a beam of electrons and deduced element 43 was present by examining X-ray diffraction spectrograms. The wavelength of the X-rays produced is related to the atomic number by a formula derived by Henry Moseley in

1913. The team claimed to detect a faint X-ray signal at a wavelength

produced by element 43. Later experimenters could not replicate the

discovery, and it was dismissed as an error for many years. Still, in 1933, a series of articles on the discovery of elements quoted the name masurium for element 43. Debate still exists as to whether the 1925 team actually did discover element 43.

The discovery of element 43 was finally confirmed in a December 1936 experiment at the University of Palermo in Sicily conducted by Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segrè. In mid 1936, Segrè visited the United States, first Columbia University in New York and then the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. He persuaded cyclotron inventor Ernest Lawrence to let him take back some discarded cyclotron parts that had become radioactive. Lawrence mailed him a molybdenum foil that had been part of the deflector in the cyclotron.

Segrè enlisted his colleague Perrier to attempt to prove, through comparative chemistry, that the molybdenum activity was indeed Z = 43. They succeeded in isolating the isotopes technetium - 95 and technetium - 97. University of Palermo officials wanted them to name their discovery "panormium", after the Latin name for Palermo, Panormus. In 1947 element 43 was named after the Greek word τεχνητός, meaning "artificial", since it was the first element to be artificially produced. Segrè returned to Berkeley and met Glenn T. Seaborg. They isolated the metastable isotope technetium - 99m, which is now used in some ten million medical diagnostic procedures annually.

In 1952, astronomer Paul W. Merrill in California detected the spectral signature of technetium (in particular, light with wavelength of 403.1 nm, 423.8 nm, 426.2 nm, and 429.7 nm) in light from S-type red giants. The stars were near the end of their lives, yet were rich in this short lived element, meaning nuclear reactions within the stars must be producing it. This evidence was used to bolster the then unproven theory that stars are where nucleosynthesis of the heavier elements occurs. More recently, such observations provided evidence that elements were being formed by neutron capture in the s-process.

Since

its discovery, there have been many searches in terrestrial materials

for natural sources of technetium. In 1962, technetium - 99 was isolated

and identified in pitchblende from the Belgian Congo in extremely small quantities (about 0.2 ng/kg); there it originates as a spontaneous fission product of uranium - 238. There is also evidence that the Oklo natural nuclear fission reactor produced significant amounts of technetium - 99, which has since decayed into ruthenium - 99.

Technetium is a silvery - gray radioactive metal with an appearance similar to that of platinum. It is commonly obtained as a gray powder. The crystal structure of the pure metal is hexagonal close - packed. Atomic technetium has characteristic emission lines at these wavelengths of light: 363.3 nm, 403.1 nm, 426.2 nm, 429.7 nm, and 485.3 nm.

The metal form is slightly paramagnetic, meaning its magnetic dipoles align with external magnetic fields, but will assume random orientations once the field is removed. Pure, metallic, single - crystal technetium becomes a type-II superconductor at temperatures below 7.46 K. Below this temperature, technetium has a very high magnetic penetration depth, the largest among the elements apart from niobium.

Technetium is placed in the seventh group of the periodic table, between rhenium and manganese. As predicted by periodic law, its chemical properties are therefore intermediate between those two elements. Of the two, technetium more closely resembles rhenium, particularly in its chemical inertness and tendency to form covalent bonds. Unlike manganese, technetium does not readily form cations (ions with a net positive charge). Common oxidation states of technetium include +4, +5, and +7. Technetium dissolves in aqua regia, nitric acid, and concentrated sulfuric acid, but it is not soluble in hydrochloric acid of any concentration.

Reaction of technetium with hydrogen produces the negatively charged hydride [TcH9]2− ion, which has the same type of crystal structure as (isostructural with) [ReH9]2−. It consists of a trigonal prism with a technetium atom in the center and six hydrogen atoms at

the corners. Three more hydrogens make a triangle lying parallel to the

base and crossing the prism in its center. Although those hydrogen

atoms are not equivalent geometrically, their electronic structure is

almost the same. This complex has a coordination number of

9 (meaning that the Tc atom has nine neighbors), which is the highest

for a technetium complex. Two hydrogen atoms in the complex can be

replaced by sodium (Na+) or potassium (K+) ions.

The metal form of technetium slowly tarnishes in moist air, and in powder form will burn in oxygen. Two oxides have been observed: TcO2 and Tc2O7. Under oxidizing conditions, which tend to strip electrons from atoms, technetium (VII) will exist as the pertechnetate ion, TcO−

4.

At temperatures of 400 – 450 °C, technetium oxidizes to form pale - yellow heptoxide:

- 4 Tc + 7 O2 → 2 Tc2O7

It adopts a centrosymmetric structure with two types of Tc-O bonds; their bond lengths are 167 and 184 pm, and the O-Tc-O angle is 180°.

Technetium heptoxide is the precursor to sodium pertechnetate:

- Tc2O7 + 2 NaOH → 2 NaTcO4 + H2O

Black - colored technetium dioxide (TcO2) can be produced by reduction of heptoxide with technetium or hydrogen.

Pertechnetic acid (HTcO4) is produced by reacting Tc2O7 with water or oxidizing acids, such as nitric acid, concentrated sulfuric acid, aqua regia, or a mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acids. The resulting dark red, hygroscopic (water absorbing) substance is a strong acid and easily donates protons. In concentrated sulfuric acid Tc (VII) tetraoxidotechnetate anion converts to the octahedral form of technetic (VII) acid TcO3(OH)(H2O)2.

The pertechnate (tetroxidotechnetate) anion TcO4− consists of a tetrahedron with oxygens in the corners and Tc atom in the center. Unlike permanganate (MnO4−), it is only a weak oxidizing agent. Pertechnate is often used as a convenient water soluble source of Tc isotopes, such as 99mTc, and as a catalyst.

Technetium forms various sulfides. TcS2 is obtained by direct reaction of technetium and elemental sulfur, while Tc2S7 is formed from the pertechnic acid as follows:

- 2 HTcO4 + 7 H2S → Tc2S7 + 8 H2O

In this reaction technetium is reduced to Tc (IV) while exess sulfur forms a disulfide ligand. The produced technetium heptasulfide has a polymeric structure (Tc3(µ3–S)(S2)3S6)n with a core similar to Mo3(µ3–S)(S2)62–.

Upon heating, technetium heptasulfide decomposes into disulfide and elementary sulfur:

- Tc2S7 → 2 TcS2 + 3 S

Analogous reactions occur with selenium and tellurium.

Several technetium clusters are known, including Tc4, Tc6, Tc8 and Tc13. The more stable Tc6 and Tc8 clusters

have prism shapes where vertical pairs of Tc atoms are connected by

triple bonds and the planar atoms by single bonds. Every Tc atom makes

six bonds, and the remaining valence electrons can be saturated by one

axial and two bridging ligand halogen atoms such as chlorine or bromine.

Technetium forms numerous organic complexes, which are relatively well investigated because of their importance for nuclear medicine. Technetium carbonyl (Tc2(CO)10) is a white solid. In this molecule, two technetium atoms are weakly bound to each other; each atom is surrounded by octahedra of five carbonyl ligands. The bond length between Tc atoms, 303 pm, is significantly larger than the distance between two atoms in metallic technetium (272 pm). Similar carbonyls are formed by manganese and rhenium.

A technetium complex with an organic ligand is commonly used in nuclear medicine. It has a unique Tc-O functional group (moiety) oriented perpendicularly to the plane of the molecule, where the oxygen atom can be replaced by a nitrogen atom.

Technetium, atomic number (Z) 43, is the lowest numbered element in the periodic table that is exclusively radioactive. The second lightest radioactive element, promethium, has an atomic number of 61. Atomic nuclei with an odd number of protons are less stable than those with even numbers, even when the total number of nucleons (protons + neutrons) are even. Odd numbered elements therefore have fewer stable isotopes.

The most stable radioactive isotopes are technetium - 98 with a half-life of 4.2 million years (Ma), technetium - 97 (half-life: 2.6 Ma) and technetium - 99 (half-life: 211,000 years). Thirty other radioisotopes have been characterized with mass numbers ranging from 85 to 118. Most of these have half-lives that are less than an hour; the exceptions are technetium - 93 (half-life: 2.73 hours), technetium - 94 (half-life: 4.88 hours), technetium - 95 (half-life: 20 hours), and technetium - 96 (half-life: 4.3 days).

The primary decay mode for isotopes lighter than technetium - 98 (98

43Tc) is electron capture, giving molybdenum (Z=42). For heavier isotopes, the primary mode is beta emission (the loss of an electron or positron), giving ruthenium (Z=44), with the exception that technetium - 100 can decay both by beta emission and electron capture.

Technetium also has numerous nuclear isomers, which are isotopes with one or more excited nucleons. Technetium - 97m (97mTc ; 'm' stands for metastability) is the most stable, with a half-life of 91 days (0.0965 MeV). This is followed by technetium - 95m (half-life: 61 days, 0.03 MeV), and technetium - 99m (half-life: 6.01 hours, 0.142 MeV). Technetium - 99m only emits gamma rays and decays to technetium - 99.

Technetium - 99 (99

43Tc) is a major product of the fission of uranium - 235 (235

92U), making it the most common and most readily available Tc isotope. One gram of technetium - 99 produces 6.2×108 disintegrations a second (that is, 0.62 GBq/g).

Only minute traces occur naturally in the Earth's crust as a spontaneous fission product in uranium ores. A kilogram of uranium contains an estimated 1 nanogram (10−9 g) of technetium. Some red giant stars with the spectral types S-, M-, and N contain an absorption line in their spectrum indicating the presence of technetium. These red - giants are known informally as technetium stars.

In contrast with its rare natural occurrence, bulk quantities of technetium - 99 are produced each year from spent nuclear fuel rods, which contain various fission products. The fission of a gram of uranium - 235 in nuclear reactors yields 27 mg of technetium - 99, giving technetium a fission product yield of 6.1%. Other fissile isotopes also produce similar yields of technetium, such as 4.9% from uranium - 233 and 6.21% from plutonium - 239. About 49,000 TBq (78 metric tons) of technetium is estimated to have been produced in nuclear reactors between 1983 and 1994, which is by far the dominant source of terrestrial technetium. Only a fraction of the production is used commercially.

Technetium - 99 is produced by the nuclear fission of both uranium - 235 and plutonium - 239. It is therefore present in radioactive waste and in the nuclear fallout of fission bomb explosions. Its decay, measured in becquerels per amount of spent fuel, is dominant after about 104 to 106 years after the creation of the nuclear waste. From 1945 to 1994, an estimated 160 TBq (about 250 kg) of technetium - 99 was released into the environment by atmospheric nuclear tests. The

amount of technetium - 99 from nuclear reactors released into the

environment up to 1986 is on the order of 1000 TBq (about

1600 kg), primarily by nuclear fuel reprocessing;

most of this was discharged into the sea. Reprocessing methods have

reduced emissions since then, but as of 2005 the primary release of

technetium - 99 into the environment is by the Sellafield plant, which released an estimated 550 TBq (about 900 kg) from 1995 – 1999 into the Irish Sea. From 2000 onwards the amount has been limited by regulation to 90 TBq (about 140 kg) per year. Discharge of technetium into the sea has resulted in some seafood containing minuscule quantities of this element. For example, European lobster and fish from west Cumbria contain about 1 Bq/kg of technetium.

The vast majority of the technetium - 99m used in medical work is produced by irradiating highly enriched uranium targets in a reactor, extracting molybdenum - 99 from the targets, and recovering the technetium - 99m that is produced upon decay of molybdenum - 99.

Almost two - thirds of the world's supply comes from two reactors; the National Research Universal Reactor at Chalk River Laboratories reactor in Ontario, Canada, and the Petten nuclear reactor of the Netherlands. All major technetium - 99m producing reactors were built in the 1960s and are close to the end of their lifetime. The two new Canadian Multipurpose Applied Physics Lattice Experiment reactors planned and built to produce 200% of the demand of technetium - 99m relieved all other producers from building their own reactors. With the cancellation of the already tested reactors in 2008 the future supply of technetium - 99m became very problematic.

However

the Chalk River reactor has been shut down for maintenance since August

2009, with an expected reopening in April 2010, and the Petten reactor

had a 6-month scheduled maintenance shutdown beginning on Friday,

February 19, 2010. With millions of procedures relying on technetium -

99m

every year, the low supply has left a gap, leaving some practitioners

to revert to techniques not used for 20 years. Somewhat allaying this

issue is an announcement from a Polish research reactor, the Maria, that

they have developed a technique to isolate technetium. The reactor at Chalk River Laboratory reopened in August 2010 and the Petten reactor reopened September 2010.

The long half-life of technetium - 99 and its ability to form an anionic species makes it a major concern for long term disposal of radioactive waste. Many of the processes designed to remove fission products in reprocessing plants aim at cationic species like caesium (e.g., caesium - 137) and strontium (e.g., strontium - 90). Hence the pertechnetate is able to escape through these treatment processes. Current disposal options favor burial in continental, geologically stable rock. The primary danger with such a course is that the waste is likely to come into contact with water, which could leach radioactive contamination into the environment. The anionic pertechnetate and iodide do not adsorb well onto the surfaces of minerals, so they are likely to be washed away. By comparison plutonium, uranium, and caesium are much more able to bind to soil particles. For this reason, the environmental chemistry of technetium is an active area of research.

An alternative disposal method, transmutation, has been demonstrated at CERN for technetium - 99. This transmutation process is one in which the technetium (technetium - 99 as a metal target) is bombarded with neutrons to form the short lived technetium - 100 (half-life = 16 seconds) which decays by beta decay to ruthenium - 100. If recovery of usable ruthenium is a goal, an extremely pure technetium target is needed; if small traces of the minor actinides such as americium and curium are present in the target, they are likely to undergo fission and form more fission products which increase the radioactivity of the irradiated target. The formation of ruthenium - 106 (half-life 374 days) from the 'fresh fission' is likely to increase the activity of the final ruthenium metal, which will then require a longer cooling time after irradiation before the ruthenium can be used.

The

actual production of technetium - 99 from spent nuclear fuel is a long

process. During fuel reprocessing, it appears in the waste liquid, which

is highly radioactive. After sitting for several years, the

radioactivity falls to a point where extraction of the long lived

isotopes, including technetium - 99, becomes feasible. Several chemical

extraction processes are then used, yielding technetium - 99 metal of high

purity.

The metastable isotope technetium - 99m is produced as a fission product from the fission of uranium or plutonium in nuclear reactors.

Because used fuel is allowed to stand for several years before

reprocessing, all molybdenum - 99 and technetium - 99m will have decayed by

the time that the fission products are separated from the major actinides in conventional nuclear reprocessing. The liquid left after plutonium – uranium extraction (PUREX) contains a high concentration of technetium as TcO−

4 but almost all of this is technetium - 99, not technetium - 99m.

Molybdenum - 99 can be formed by the neutron activation of molybdenum - 98. Molybdenum - 99 has a half-life of 67 hours, so short lived technetium - 99m (half-life: 6 hours), which results from its decay, is being constantly produced. The technetium can then be chemically extracted from the solution by using a technetium - 99m generator ("technetium cow", also occasionally called a "molybdenum cow"). By irradiating a highly enriched uranium target to produce molybdenum - 99, there is no need for the complex chemical steps which would be required to separate molybdenum from a fission product mixture. This method requires that an enriched uranium target be irradiated with neutrons to form molybdenum - 99 as a fission product, then separated. A drawback of this process is that it requires targets containing uranium - 235, which are subject to the security precautions of fissile materials.

Other

technetium isotopes are not produced in significant quantities by

fission; when needed, they are manufactured by neutron irradiation of

parent isotopes (for example, technetium - 97 can be made by neutron

irradiation of ruthenium - 96).

Technetium - 99m ("m" indicates that this is a metastable nuclear isomer) is used in radioactive isotope medical tests, for example as a radioactive tracer that medical equipment can detect in the human body. It is well suited to the role because it emits readily detectable 140 keVgamma rays, and its half-life is 6.01 hours (meaning that about 94% of it decays to technetium - 99 in 24 hours). There are at least 31 commonly used radiopharmaceuticals based on technetium - 99m for imaging and functional studies of the brain, myocardium, thyroid, lungs, liver, gallbladder, kidneys, skeleton, blood, and tumors.

The longer lived isotope technetium - 95m, with a half-life of 61 days, is used as a radioactive tracer to study the movement of technetium in the environment and in plant and animal systems.

Technetium - 99 decays almost entirely by beta decay, emitting beta particles with consistent low energies and no accompanying gamma rays. Moreover, its long half-life means that this emission decreases very slowly with time. It can also be extracted to a high chemical and isotopic purity from radioactive waste. For these reasons, it is a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) standard beta emitter, and is therefore used for equipment calibration. Technetium - 99 has also been proposed for use in optoelectronic devices and nanoscale nuclear batteries.

Like rhenium and palladium, technetium can serve as a catalyst. For some reactions, for example the dehydrogenation of isopropyl alcohol, it is a far more effective catalyst than either rhenium or palladium. However, its radioactivity is a major problem in finding safe catalytic applications.

When steel is immersed in water, adding a small concentration (55 ppm) of potassium pertechnetate (VII) to the water protects the steel from corrosion, even if the temperature is raised to 250 °C. For this reason, pertechnetate has been used as a possible anodic corrosion inhibitor for steel, although technetium's radioactivity poses problems which limit this application to self - contained systems. While (for example) CrO42− can also inhibit corrosion, it requires a concentration ten times as high. In one experiment, a specimen of carbon steel was kept in an aqueous solution of pertechnetate for 20 years and was still uncorroded. The mechanism by which pertechnetate prevents corrosion is not well understood, but seems to involve the reversible formation of a thin surface layer. One theory holds that the pertechnetate reacts with the steel surface to form a layer of technetium dioxide which prevents further corrosion; the same effect explains how iron powder can be used to remove pertechnetate from water. (Activated carbon can also be used for the same effect.) The effect disappears rapidly if the concentration of pertechnetate falls below the minimum concentration or if too high a concentration of other ions is added.

As noted, the radioactive nature of technetium (3 MBq per

liter at the concentrations required) makes this corrosion protection

impractical in almost all situations. Nevertheless, corrosion protection

by pertechnetate ions was proposed (but never adopted) for use in boiling water reactors.

Technetium plays no natural biological role and is not normally found in the human body. Technetium is produced in quantity by nuclear fission, and spreads more readily than many radionuclides. It appears to have low chemical toxicity. For example, no significant change in blood formula, body and organ weights, and food consumption could be detected for rats which ingested up to 15 µg of technetium - 99 per gram of food for several weeks. The radiological toxicity of technetium (per unit of mass) is a function of compound, type of radiation for the isotope in question, and the isotope's half-life.

All

isotopes of technetium must be handled carefully. The most common

isotope, technetium - 99, is a weak beta emitter; such radiation is

stopped by the walls of laboratory glassware. The primary hazard when

working with technetium is inhalation of dust; such radioactive contamination in the lungs can pose a significant cancer risk. For most work, careful handling in a fume hood is sufficient; a glove box is not needed.

Carlo Perrier (1886 - 1948) was an Italian mineralogist who did extensive research on the element technetium in 1936. He discovered the element along with his colleague, Emilio Segrè (1905 - 1989), in 1937.

Emilio Gino Segrè (1 February 1905 – 22 April 1989) was an Italian born, naturalized American, physicist and Nobel laureate in physics, who with Owen Chamberlain, discovered antiprotons, a sub - atomic antiparticle.

Segrè was born into a Sephardic Jewish family in Tivoli, near Rome, and enrolled in the University of Rome La Sapienza as an engineering student. He switched to physics in 1927 and earned his doctorate in 1928, having studied under Enrico Fermi.

After a stint in the Italian Army from 1928 to 1929, he worked with Otto Stern in Hamburg and Pieter Zeeman in Amsterdam as a Rockefeller Foundation fellow in 1930. Segrè was appointed assistant professor of physics at the University of Rome in 1932 and served until 1936. From 1936 to 1938 he was Director of the Physics Laboratory at the University of Palermo. After a visit to Ernest O. Lawrence's Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, he was sent a molybdenum strip from the laboratory's cyclotron deflector in 1937 which was emitting anomalous forms of radioactivity. After careful chemical and theoretical analysis, Segrè was able to prove that some of the radiation was being produced by a previously unknown element, dubbed technetium, and was the first artificially synthesized chemical element which does not occur in nature.

He was a colleague and close friend of Ettore Majorana, who disappeared mysteriously in 1938.

While Segrè was on a summer visit to California in 1938, Benito Mussolini's fascist government passed anti - Semitic laws barring Jews from university positions. As a Jew, Segrè was now rendered an indefinite émigré. At the Berkeley Radiation Lab, Lawrence offered him a job as a Research Assistant — a relatively lowly position for someone who had discovered an element — for US$ 300 a month. However, in Segrè's recollection, when Lawrence learned that Segrè was legally trapped in California, he reduced his salary to US$ 116 a month which many, including Segrè, saw as exploiting the situation. Segrè also found work as a lecturer of the physics department at the University of California, Berkeley.

While at Berkeley, he helped discover the element astatine and the isotope plutonium - 239 (which was later used to make Fat Man, the atom bomb dropped on Nagasaki). He found in April 1944 that Thin Man,

the proposed plutonium "gun - type" bomb, would not work (because of the

presence of Pu-240 impurities), and priority was given to Fat Man, the

plutonium "implosion" bomb.

From 1943 to 1946 he worked at the Los Alamos National Laboratory as a group leader for the Manhattan Project. In 1944, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States. He taught at Columbia University, University of Illinois and University of Rio de Janeiro. On his return to Berkeley in 1946, he became a professor of physics and of the history of science, serving until 1972.

Professors Emilio Segrè and Owen Chamberlain were co-heads of a research group at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory. Their group proposed the experiment to discover the anti - proton and this was the chief reason that the Bevatron was built at LRL. The Bevatron was designed to reach proton energies of 6.2 m0c2 where mo is the rest mass of the proton. With the new Bevatron, the Segrè / Chamberlain group produced the first anti - proton (as seen in bubble chamber pictures) and the two shared the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physics for their work.

In 1970, Segrè published a biography of Fermi (Enrico Fermi: Physicist, University of Chicago Press)

In 1974 he returned to the University of Rome as a professor of nuclear physics.

Segrè was also active as a photographer, and took many photos documenting events and people in the history of modern science. The American Institute of Physics named its photographic archive of physics history in his honor. Segrè died at the age of 84 of a heart attack.