<Back to Index>

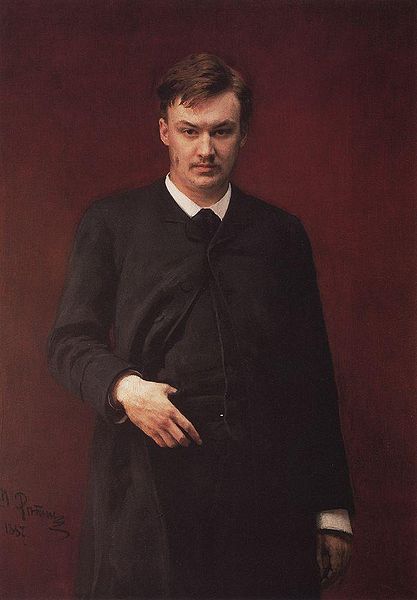

- Composer Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov, 1865

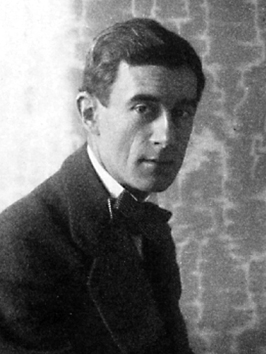

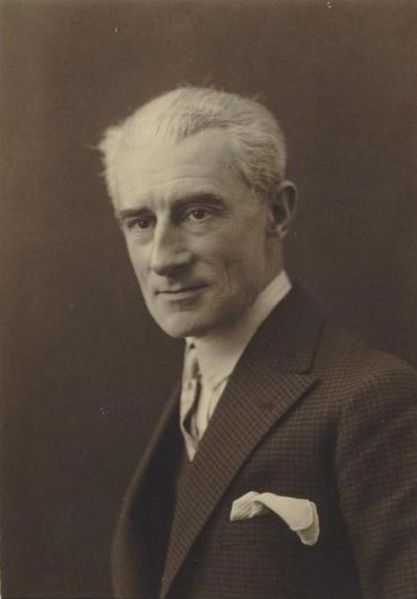

- Composer Joseph - Maurice Ravel, 1875

PAGE SPONSOR

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov (10 August 1865 – 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer of the late Russian Romantic period, music teacher and conductor. He served as director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 and 1928 and was also instrumental in the reorganization of the institute into the Petrograd Conservatory, then the Leningrad Conservatory, following the Bolshevik Revolution. He continued heading the Conservatory until 1930, though he had left the Soviet Union in 1928 and did not return. The best known student under his tenure during the early Soviet years was Dmitri Shostakovich.

Glazunov was significant in that he successfully reconciled nationalism and cosmopolitanism in Russian music. While he was the direct successor to Balakirev's nationalism, he tended more towards Borodin's epic grandeur while absorbing a number of other influences. These included Rimsky - Korsakov's orchestral virtuosity, Tchaikovsky's lyricism and Taneyev's contrapuntal skill. His weaknesses were a streak of academicism which sometimes overpowered his inspiration and an eclecticism which could sap the ultimate stamp of originality from his music. Younger composers such as Prokofiev and

Shostakovich eventually considered his music old fashioned while also

admitting he remained a composer with an imposing reputation and a

stabilizing influence in a time of transition and turmoil.

Glazunov was born in Saint Petersburg, the son of a wealthy publisher. He began studying piano at age of nine and began composing at 11. Mily Balakirev, former leader of the nationalist group "The Five", recognized Glazunov's talent and brought his work to the attention of Nikolai Rimsky - Korsakov. "Casually Balakirev once brought me the composition of a fourteen or fifteen year old high school student, Sasha Glazunov", Rimsky - Korsakov remembered. "It was an orchestral score written in childish fashion. The boy's talent was indubitably clear." Balakirev introduced him to Rimsky - Korsakov shortly afterwards, in December 1879. Rimsky - Korsakov premiered this work in 1882, when Glazunov was 16. Borodin and Stasov, among others, lavishly praised both the work and its composer.

Rimsky - Korsakov taught Glazunov as a private student. "His musical development progressed not by the day, but literally by the hour", Rimsky - Korsakov wrote. The

nature of their relationship also changed. By the spring of 1881,

Rimsky - Korsakov considered Glazunov more of a junior colleague than a

student. While part of this development may have been from Rimsky - Korsakov's need to find a spiritual replacement for Modest Mussorgsky, who had died that March, it may have also been from observing his progress on the first of Glazunov's eight symphonies.

More important than this praise was that among the work's admirers was a wealthy timber merchant and amateur musician, Mitrofan Belyayev. Belyayev was introduced to Glazunov's music by Anatoly Lyadov and would take a keen interest in the teenager's musical future, then extend that interest to an entire group of nationalist composers. Belyayev took Glazunov on a trip to Western Europe in 1884. Glazunov met Liszt in Weimar, where Glazunov's First Symphony was performed.

Also in 1884, Belyayev rented out a hall and hired an orchestra to play Glazunov's First Symphony plus an orchestral suite Glazunov had just composed. Buoyed by the success of the rehearsal, Belyayev decided the following season to give a public concert of works by Glazunov and other composers. This project grew into the Russian Symphony Concerts, which were inaugurated during the 1886 – 1887 season.

In 1885 Belyayev started his own publishing house in Leipzig, Germany, initially publishing music by Glazunov, Lyadov, Rimsky - Korsakov and Borodin at his own expense. Young composers started appealing for his help. To help select from their offerings, Belyayev asked Glazunov to serve with Rimsky - Korsakov and Lyadov on an advisory council. The group of composers that formed eventually became known at the Belyayev Circle.

Glazunov

soon enjoyed international acclaim. Nevertheless, he experienced a

creative crisis in 1890 – 1891. He came out of this period with a new

maturity. During the 1890s he wrote three symphonies, two string

quartets and the ballet Raymonda.

By the time he was elected director of the Saint Petersburg

Conservatory in 1905, he was at the height of his creative powers. His

best works from this period are considered his Eighth Symphony and Violin Concerto.

This was also the time of his greatest international acclaim. He

conducted the last of the Russian Historical Concerts in Paris on 17 May

1907 and received honorary Doctor of Music degrees

from the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. There were also cycles

of all - Glazunov concerts in Saint Petersburg and Moscow to celebrate his

25th anniversary as a composer.

Glazunov made his conducting debut in 1888. The following year, he conducted his Second Symphony in Paris at the World Exhibition. He was appointed conductor for the Russian Symphony Concerts in 1896. In March of that year he conducted the posthumous premiere of Tchaikovsky's student overture The Storm. In 1897, he led the disastrous premiere of Rachmaninoff's Symphony No 1. The composer's wife later claimed that Glazunov seemed to be drunk at the time. While this assertion cannot be confirmed, it is not implausible for a man who, according to Shostakovich, kept a bottle of alcohol hidden behind his desk and sipped it through a tube during lessons.

Drunk or not, Glazunov had insufficient rehearsal time with the symphony and, while he loved the art of conducting, he never fully mastered it. From time to time he conducted his own compositions, especially the ballet Raymonda, even though he may have known he had no talent for it. He would sometimes joke, "You can criticize my compositions, but you cannot deny that I am a good conductor and a remarkable conservatory Director."

Despite the hardships he suffered during World War I and the ensuing Russian Civil War, Glazunov remained active as a conductor. He conducted concerts in factories, clubs and Red Army posts. He played a prominent part in the Russian observation in 1927 of the centenary of Beethoven's

death, as both speaker and conductor. After he left Russia, he

conducted an evening of his works in Paris in 1928. This was followed by

engagements in Portugal, Spain, France, England, Czechoslovakia,

Poland, the Netherlands and the United States.

In 1899, Glazunov became a professor at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. In the wake of the 1905 Russian Revolution and firing, then re-hiring of Rimsky - Korsakov that year, Glazunov became its director. He remained so until the revolutionary events of 1917, which culminated on 7 November. His Piano Concerto No. 2 in B minor, Op. 100, which he conducted, was premiered at the first concert held in Petrograd after that date. After the end of World War I, he was instrumental in the reorganization of the Conservatory — this may, in fact, have been the main reason he waited so long to go into exile. During his tenure he worked tirelessly to improve the curriculum, raise the standards for students and staff, as well as defend the institute's dignity and autonomy. Among his achievements were an opera studio and a students' philharmonic orchestra.

Glazunov showed paternal concern for the welfare of needy students, such as Dmitri Shostakovich and Nathan Milstein. He also personally examined hundreds of students at the end of each academic year, writing brief comments on each. Unfortunately, according to Shostakovich's comments in Testimony, Glazunov's alcoholism may have progressed to the point that he could not give a lesson while sober. Glazunov taught only chamber music by the time Shostakovich was a student. Glazunov sat at his desk, not interrupting the music being played during class. He spoke quietly and briefly, his comments becoming less distinct and briefer toward the end of the lesson.

While Glazunov's sobriety could be questioned, his prestige was not. Because of his reputation, the Conservatory received special status among institutions of higher learning in the aftermath of the October Revolution. Glazunov established a sound working relationship with the Bolshevik regime, especially with Anatoly Lunacharsky, the minister of education. Nevertheless, Glazunov's conservatism was attacked within the Conservatory. Increasingly, professors demanded more progressive methods, and students wanted greater rights. Glazunov saw these demands as both destructive and unjust. Tired of the Conservatory, he took advantage of the opportunity to go abroad in 1928 for the Schubert centenary celebrations in Vienna. He did not return. Maximilian Steinberg ran the Conservatory in his absence until Glazunov finally resigned in 1930.

Glazunov toured Europe and the United States in 1928, and settled in Paris by 1929. He always claimed that the reason for his continued absence from Russia was "ill health"; this enabled him to remain a respected composer in the Soviet Union, unlike Stravinsky and Rachmaninoff, who had left for other reasons. In 1929, he conducted an orchestra of Parisian musicians in the first complete electrical recording of The Seasons. In 1934, he wrote his Saxophone Concerto, a virtuoso and lyrical work for the alto saxophone.

In 1929, at age 64, Glazunov married the 54 year old Olga Nikolayevna Gavrilova (1875 – 1968). The

previous year, Olga's daughter Elena Gavrilova had been the soloist in

the first Paris performance of his Piano Concerto No. 2 in B major,

Op. 100. He

subsequently adopted Elena (she is sometimes referred to as his

stepdaughter), and she then used the name Elena Glazunova. In 1928,

Elena had married the pianist Sergei Tarnowsky, who managed Glazunov's professional and business affairs in Paris, such as negotiating his United States appearances with Sol Hurok. Elena later appeared as Elena Gunther - Glazunova after her second marriage, to Herbert Gunther (1906 – 1978).

Glazunov died in Neuilly - sur - Seine (near Paris) at the age of 70 in 1936. The announcement of his death shocked many. They had long associated Glazunov with the music of the past rather than of the present, so they thought he had already been dead for many years.

In 1972 his remains were reinterred in Leningrad.

Glazunov was acknowledged as a great prodigy in his field and, with the help of his mentor and friend Rimsky - Korsakov, finished some of Alexander Borodin's great works, the most famous being the Third Symphony and the opera Prince Igor, including the popular Polovtsian Dances. He reconstructed the overture from memory, having heard it played on the piano only once. Shostakovich reports, however, that Glazunov told him when drunk that his "reconstruction" of Borodin's overture was actually original work; Glazunov chose to give full credit to Borodin for the composition which he, Glazunov, wrote. Glazunov's ability to perfectly mimic Borodin's style is a tribute to his musical creativity. His giving the credit to Borodin, Shostakovich felt, said much for Glazunov's character. "It doesn't happen often that a man composes excellent music for another composer and doesn't advertise it (to talk while drinking doesn't count). It's usually the other way around — a man steals an idea or even a considerable piece of music and passes it off as his own."

Shostakovich mentioned in Testimony that there were many similar stories about Glazunov's memory. One of the more famous ones, he recalled, was when Sergei Taneyev came to Saint Petersburg with a new symphony. The person whom Taneyev was visiting hid the teenage Glazunov in the next room. Taneyev played his symphony on the piano for the host. The other guests praised and congratulated him. The host then told Taneyev, "I'd like you to meet a talented young man. He's also written a symphony." He brought Glazunov in from the next room. The host said, "Sasha, show your symphony to our dear guest." Glazunov sat down at the piano and played Taneyev's symphony from beginning to end, after hearing it only once and through a closed door.

Age

did not weaken Glazunov's memory. Another story Shostakovich relayed

was of an "eternal student" applying to enter the composition department

at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory. The applicant played a piano

sonata he had written. Glazunov listened. When the applicant had

finished, Glazunov said, "If I'm not mistaken, you applied a few years

ago. Then, in another sonata, you had quite a good secondary theme."

Glazunov sat down at the keyboard and played a large segment of the old

sonata. "The secondary theme was rubbish, of course", Shostakovich said,

"but the effect was enormous."

Glazunov's most popular works nowadays are his ballets The Seasons and Raymonda, some of his later symphonies, particularly the Fourth, Fifth and Sixth, the Polonaise from Les Sylphides, and his two Concert Waltzes. His Violin Concerto, which was a favorite vehicle for Jascha Heifetz, is still sometimes played and recorded. His last work, the Saxophone Concerto (1934), showed his ability to adapt to Western fashions in music at that time. The earlier rebellions of the experimental, serialist and minimalist movements passed him by and he never shied away from the polished manner he had perfected at the turn of the century.

Glazunov's musical development was paradoxical. He was adopted as an idol by nationalist composers who had been largely self taught and, apart from Rimsky - Korsakov, deeply distrustful of academic technique. Glazunov's first two symphonies could be seen as an anthology of nationalist techniques as practiced by Balakirev and Borodin; the same could be said for his symphonic poem Stenka Razin with its use of the folk song "Volga Boatmen" and orientalist practices much like those employed by The Five. By his early 20's he realized the polemic battles between academicism and nationalism were no longer valid. Although he based his compositions on Russian popular music, Glazunov's technical mastery allowed him to write in a sophisticated, cultured idiom. With his Third Symphony, he consciously attempted to internationalize his music in a manner similar to Tchaikovsky, to whom the piece is dedicated.

The Third Symphony was a transitional work. Glazunov admitted its composition caused him a great deal of trouble. With the Fourth Symphony, he came into his mature style. Dedicated to Anton Rubinstein, the Fourth was written as a deliberately cosmopolitan work by a Russian looking outward to the West, yet it remained unmistakably Russian in tone. He continued to synthesize nationalist tradition and Western technique in the Fifth Symphony. By the time Glazunov wrote his Seventh Symphony, his duties at the Conservatory had slowed his rate of composition. After his Eighth Symphony, his heavy drinking may have started taking a toll on his creativity, as well. He sketched one movement of a Ninth Symphony but left the work unfinished.

Glazunov wrote three ballets; eight symphonies and many other orchestral works; five concertos (2 for piano; 1 for violin; 1 for cello; 1 for saxophone); seven string quartets; two piano sonatas and other piano pieces; miscellaneous instrumental pieces; and some songs. He worked together with the choreographer Michel Fokine to create the ballet Les Sylphides. It was a collection of piano works by Frédéric Chopin, orchestrated by Glazunov. He was also given the opportunity by Serge Diaghilev to write music to The Firebird after Lyadov had failed to do so. Glazunov refused. Eventually, Diaghilev sought out the then unknown Igor Stravinsky, who wrote the music.

Ironically, both Glazunov and Rachmaninoff,

whose first symphony Glazunov supposedly had conducted so poorly at its

premiere (according to the composer), were considered "old - fashioned"

in their later years. In recent years, Glazunov's musical gifts have

been more fully appreciated, thanks to extensive recordings of his

complete orchestral works.

In his Chronicle, Stravinsky admitted that, as a young man, he greatly admired Glazunov's perfection of musical form, purity of counterpoint and ease and assurance of his writing. At 15, Stravinsky transcribed one of Glazunov's string quartets for piano solo. He also deliberately modeled his Symphony in E-flat, Op. 1, on Glazunov's symphonies, which were then in vogue. He used Glazunov's Eighth Symphony, Op. 83, which was written in the same key as his, as a pattern on which to base corrections to his symphony.

This attitude changed over time. In his Memoirs Stravinsky called Glazunov one of the most disagreeable men he had ever met, adding that the only bad omen he had experienced about the initial (private) performance of his symphony was Glazunov having come to him afterwards saying, "Very nice, very nice." Later, Stravinsky amended his recollection of this incident, adding that when Glazunov passed him in the aisle after the performance, he told Stravinsky, "Rather heavy instrumentation for such music."

For his part, Glazunov was not supportive of the modern direction Stravinsky's music took. He was not alone in this prejudice — their mutual teacher Rimsky - Korsakov was as profoundly conservative by the end of his life, wedded to the academic process he helped instill at the Conservatory. Unlike Rimsky - Korsakov, Glazunov was not anxious about the potential dead end Russian music might take by following academia strictly, nor did he share Rimsky - Korsakov's grudging respect for new ideas and techniques.

Chances are that Glazunov treated Stravinsky with reserve, certainly not with open rudeness. His opinion of Stravinsky's music in the presence of others was another matter. At the performance of Feu d'artifice (Fireworks), he reportedly made the comment, "Kein talent, nur Dissonanz." (Also in the audience was Sergei Diaghilev, who on the strength of this music sought out the young composer for the Ballets Russes.) Glazunov eventually considered Stravinsky merely an expert orchestrator. In 1912 he told Vladimir Telyakovsky, "Petrushka is not music, but is excellently and skillfully orchestrated."

In

1962, when Stravinsky returned to the Soviet Union to celebrate his

80th birthday, he visited the Leningrad conservatory and, according to

his associate Robert Craft, moaned and said "Glazunov!" when he saw a photograph of the composer on display.

Igor Stravinsky was not the only composer whose modernist tendencies Glazunov disliked. Shostakovich mentioned Glazunov's attacks against the "recherché cacophonists" — the elder composer's term for the newer generation of Western composers, beginning with Debussy. When Franz Schreker's opera Der ferne Klang was staged in Lenningrad, Glazunov pronounced the opera "Schreckliche Musik!" He also may have wondered occasionally whether he had played a role in spawning musical chaos. Once, while looking a score of Debussy's Prélude à l'après - midi d'un faune, he commented, "It's orchestrated with great taste.... And he knows his work.... Could it be that Rimsky and I influenced the orchestration of all these contemporary degenerates?"

To

Glazunov's credit, however, even after he had consigned a piece of

music to be "cacophonic", he did not stop listening to it. Instead, he

would continue listening in an effort to comprehend it. He "penetrated"

Wagner's music in this way; he understood nothing about Die Walküre the

first time he heard it — or the second, third, or fourth. On the tenth

hearing, he finally understood the opera and liked it very much. When

Shostakovich was one of his students, Glazunov was attempting to do the

same with Richard Strauss's Salome — "getting used to it, penetrating it, studying it", Shostakovich said.

Shostakovich entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13, becoming the youngest student there. He studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Rimsky - Korsakov's son - in - law Maximilian Steinberg. He proved to be a disciplined, hard working student. Glazunov may have recognized in Shostakovich an echo of his younger self. He carefully monitored his progress in Steinberg's class and, in awarding him his doctorate, recommended Shostakovich for a higher degree which normally would have led to a professorship. Due to his family's financial hardship, Shostakovich was not able to take advantage of this opportunity. Glazunov also arranged for the premiere of Shostakovich's First Symphony, which took place on 12 March 1926 with the Lenningrad Philharmonic under Nikolai Malko. This was 44 years after Glazunov's First Symphony had first been presented in the same hall. In another instance of déjà vu with Glazunov's early life, the symphony caused almost as much of a sensation as the appearance of the young Shostakovich on the stage awkwardly taking his bow.

Because

of Glazunov's bouts of heavy drinking, he found the ban on the official

sale of wine and vodka by the Bolskeviks a particular hardship. However, he learned Shostakovich's father had access to spirit alcohol,

which was strictly rationed. One of Shostakovich's more onerous tasks

became relaying requests between Glazunov and his father. He found this

troubling for two reasons. First, the requests could place his father in

mortal danger, particularly since it was impossible to tell whom the

Bolsheviks would decide to shoot as an example to others. Second, he did

not wish anyone to attribute his success at the Conservatory to

bribery.

Dmitri Shostakovich admitted that while there was much about Glazunov that he found incomprehensible, even laughable, Glazunov willingly sacrificed his time, his peace of mind and his creativity for the Conservatory. He spent practically all his time there. He became calm and firm in dealing with the authorities. When asked before the Revolution how many Jews were enrolled, Glazunov sent the reply, "We don't keep count here." In 1922, the government decided to give Glazunov living conditions that would facilitate his creativity and be commensurate with his achievements. Glazunov, who had lost a tremendous amount of weight and was living as hard a life as many in that time, asked instead that the government send firewood to the Conservatory so the students could study more easily. The firewood was delivered.

He

gave away a tremendous amount of his salary to needy students out of

compassion for them. He wrote countless letters of recommendation,

writing what he really thought about the person and giving praise with

justification. Sometimes he went to government officials to plead their

case. Jewish musicians knew he would see the authorities to get them

permission to live in Petrograd. Thanks to him, Jascha Heifetz, Nathan Milstein and Mischa Elman, among others, were able to come and study. Shostakovich

claimed Glazunov never asked these musicians to play for him; he felt

everyone had a right to live where they pleased and art would not suffer

as a result. Most importantly to Shostakovich, Glazunov did not call

attention to his efforts in this regard. "He didn't demonstrate his high

principles when it came to small and pathetic people. He saved this for

more important people and more important incidents."

Joseph-Maurice Ravel (March 7, 1875 – December 28, 1937) was a French composer known especially for his melodies, orchestral and instrumental textures and effects. Much of his piano music, chamber music, vocal music and orchestral music has entered the standard concert repertoire.

Ravel's piano compositions, such as Jeux d'eau, Miroirs, Le tombeau de Couperin and Gaspard de la nuit, demand considerable virtuosity from the performer, and his orchestral music, including Daphnis et Chloé and his arrangement of Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition, uses a variety of sound and instrumentation.

Ravel is perhaps known best for his orchestral work Boléro (1928), which he considered trivial and once described as "a piece for orchestra without music".

According to SACEM, Ravel's estate earns more royalties than that of any other French composer. According to international copyright law, Ravel's works have been in the public domain since January 1, 2008, in most countries.

Ravel was born in the Basque town of Ciboure, France, near Biarritz, close to the border with Spain, in 1875. His mother, Marie Delouart, was of Basque descent and grew up in Madrid, Spain, while his father, Joseph Ravel, was a Swiss inventor and industrialist from French Haute - Savoie. Both were Catholics and they provided a happy and stimulating household for their children. Some of Joseph's inventions were quite important, including an early internal combustion engine and a notorious circus machine, the "Whirlwind of Death", an automotive loop - the - loop that was quite a success until a fatal accident at the Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1903. Joseph delighted in taking his sons to factories to see the latest mechanical devices, and he also had a keen interest in music and culture. Ravel substantiated his father's early influence by stating later, “As a child, I was sensitive to music — to every kind of music.”

Ravel was very fond of his mother, and her Basque - Spanish heritage was a strong influence on his life and music. Among his earliest memories are folk songs she sang to him. The family moved to Paris three months after the birth of Maurice, and there his younger brother Édouard was born. Édouard became his father’s favorite and also became an engineer. At age six, Maurice began piano lessons with Henry Ghys and received his first instruction in harmony, counterpoint, and composition with Charles - René. His earliest public piano recital was in 1889 at age fourteen.

Though obviously talented at the piano, Ravel demonstrated a preference for composing. He was particularly impressed by the new Russian works conducted by Nikolai Rimsky - Korsakov at the Exposition Universelle in 1889. The foreign music at the exhibition also had a great influence on Ravel’s contemporaries Erik Satie, Emmanuel Chabrier, and most significantly Claude Debussy. That year Ravel also met Ricardo Viñes,

who would become one of his best friends, one of the foremost

interpreters of his piano music, and an important link between Ravel and

Spanish music. The students shared an appreciation for Richard Wagner, the Russian school, and the writings of Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Baudelaire, and Stéphane Mallarmé.

Ravel’s parents encouraged his musical pursuits and sent him to the Conservatoire de Paris, first as a preparatory student and eventually as a piano major. His teachers included Émile Descombes. He received a first prize in the piano student competition in 1891. Overall, however, he was not successful academically even as his musicianship matured dramatically. Considered “very gifted”, Ravel was also called “somewhat heedless” in his studies. Around 1893, Ravel created his earliest compositions, and he was introduced by his father to the café pianist Erik Satie, whose distinctive personality and unorthodox musical experiments proved influential.

Ravel was not a "bohemian" and evidenced little of the typical trauma of adolescence. At twenty years of age, Ravel was already "self - possessed, a little aloof, intellectually biased, given to mild banter." He dressed like a dandy and was meticulous about his appearance and demeanor. Short in stature, light in frame, and bony in features, Ravel had the "appearance of a well - dressed jockey". His large head seemed suitably matched to his great intellect. He was well read and later accumulated a library of over 1,000 volumes. In his younger adulthood, Ravel was usually bearded in the fashion of the day, though later he dispensed with all whiskers. Though reserved, Ravel was sensitive and self - critical, and had a mischievous sense of humor. He became a life long tobacco smoker in his youth, and he enjoyed strongly flavored meals, fine wine, and spirited conversation.

After failing to meet the requirement of earning a competitive medal in three consecutive years, Ravel was expelled in 1895. He turned down a music professorship in Tunisia then returned to the Conservatoire in 1898 and started his studies with Gabriel Fauré, determined to focus on composing rather than piano playing. He studied composition with Fauré until he was dismissed from the class in 1900 for having won neither the fugue nor the composition prize. He remained an auditor with Fauré until he left the Conservatoire in 1903. Ravel found his teacher’s personality and methods sympathetic and they remained friends and colleagues. He also undertook private studies with André Gedalge, whom he later stated was responsible for "the most valuable elements of my technique." Ravel studied the ability of each instrument carefully in order to determine the possible effects, and was sensitive to their color and timbre. This may account for his success as an orchestrator and as a transcriber of his own piano works and those of other composers, such as Mussorgsky, Debussy and Schumann.

His first significant work, Habanera for two pianos, was later transcribed into the well known third movement of his Rapsodie espagnole, which he dedicated to Charles - Wilfrid de Bériot, another of his professors at the Conservatoire. His first published work was Menuet antique, dedicated to and premiered by Viñes. In 1899, Ravel conducted his first orchestral piece, Shéhérazade,

and was greeted by a raucous mixture of boos and applause. Critics

termed the piece "a jolting debut: a clumsy plagiarism of the Russian School" and called Ravel a “mediocrely gifted debutante ... who will perhaps become something if not someone in about ten years, if he works hard.” As

the most gifted composer of his class and as a leader, with Debussy, of

avant - garde French music, Ravel would continue to have a difficult time

with the critics for some time to come.

Around 1900, Ravel joined with a number of innovative young artists, poets, critics, and musicians who were referred to as the Apaches (hooligans), a name coined by Viñes to represent his band of "artistic outcasts". The group met regularly until the beginning of World War I and the members often inspired each other with intellectual argument and performances of their works before the group. For a time, the influential group included Igor Stravinsky and Manuel de Falla. One of the first works Ravel performed for the Apaches was Jeux d'eau, his first piano masterpiece and clearly a pathfinding impressionistic work. Viñes performed the public premiere of this piece and Ravel's other early masterpiece Pavane pour une infante défunte in 1902.

During his years at the Conservatoire, Ravel tried numerous times to win the prestigious Prix de Rome, but to no avail; he was probably considered too radical by the conservatives, including Director Théodore Dubois. One of Ravel's submitted pieces, the String Quartet in F, probably modeled on Debussy’s Quartet (1893), is now a standard work of chamber music, though at the time it was criticized and found lacking academically. In

1905, Ravel's final year of eligibility for the Prix de Rome, Ravel did

not even pass the preliminary test, despite being favored to win one of

the two first prizes available. Instead, all six selected finalists were students of Charles Lenepveu,

a member of the jury and heir apparent of Dubois as director of the

Conservatoire. The scandal – named the "Ravel Affair" by the Parisian

press – engaged the entire artistic community, pitting conservatives

against the avant - garde, and eventually caused the resignation of Dubois

and his replacement by Fauré instead of Lenepveu, a vindication

of sorts for Ravel. Alfred Edwards, editor of Le Matin, who had taken particular interest in the incident, took Ravel on a seven week canal trip on his yacht Aimée through the Low Countries in June and July 1905, the first time Ravel traveled abroad. Though

deprived of the opportunity to study in Rome, the decade after the

scandal proved to be Ravel's most productive, and included his "Spanish

period".

Ravel met Debussy in the 1890s. Debussy was older than Ravel by some twelve years and his pioneering Prélude à l'après - midi d'un faune was influential among the younger musicians including Ravel, who were impressed by the new language of impressionism. In 1900, Ravel was invited to Debussy’s home and they played each other’s works. Viñes became the preferred piano performer for both composers and a go - between. The two composers attended many of the same musical events and were performed at the same concerts. Ravel and the Apaches were strong supporters of Debussy’s controversial public debut of his unconventional opera Pelléas et Mélisande, which garnered Debussy both fame and scorn.

The two musicians also appreciated much the same musical heritage and operated in the same artistic milieu, but they differed in terms of personality and their approach to music. Debussy was considered more spontaneous and casual in his composing while Ravel was more attentive to form and craftsmanship. Even though they worked independently of one another, because they employed differing means to similar ends, and because superficial similarities and even some more substantive ones are evident, the public and the critics associated them more than the facts warranted.

Ravel wrote that Debussy’s “genius was obviously one of great individuality, creating its own laws, constantly in evolution, expressing itself freely, yet always faithful to French tradition. For Debussy, the musician and the man, I have had profound admiration, but by nature I am different from Debussy.” Ravel further stated, “I think I have always personally followed a direction opposed to that of the symbolism of Debussy.”

They admired each other’s music and Ravel even played Debussy’s work in public on occasion. However, Ravel did criticize Debussy sometimes, particularly regarding his orchestration, and he once said, "If I had the time, I would reorchestrate La mer."

By

1905, factions formed for each composer and the two groups began

feuding in public. Disputes arose as to questions of chronology about

their respective works and who influenced whom. The public tension

caused personal estrangement. As Ravel said, “It is probably better after all for us to be on frigid terms for illogical reasons.” Ravel

stoically absorbed superficial comparisons with Debussy promulgated by

biased critics, including Pierre Lalo, an anti - Ravel critic who stated,

“Where M. Debussy is all sensitivity, M. Ravel is all insensitivity,

borrowing without hesitation not only technique but the sensitivity of

other people.” During

1913, in a remarkable coincidence, both Ravel and Debussy independently

produced and published musical settings for poems by Stéphane Mallarmé,

again provoking comparisons of their work and their perceived influence

on each other, which continued even after Debussy’s death five years

later.

The next of Ravel’s piano compositions to become famous was Miroirs (Mirrors, 1905), five piano pieces which marked a “harmonic evolution” and which one commentator described as “intensely descriptive and pictorial. They banish all sentiment in expression but offer to the listener a number of refined sensory elements which can be appreciated according to his imagination.” Next was his Histoires naturelles (Nature Stories), five humorous songs evoking the presence of five animals. Two years later, Ravel completed his Rapsodie espagnole, his first major "Spanish" piece, written first for piano four hands and then scored for orchestra. Though it employs folk like melodies, no actual folk songs are quoted. It premiered in 1908 to generally good reviews, with one critic stating that it was "one of the most interesting novelties of the season", while Pierre Lalo (as usual) reacted negatively, calling it "laborious and pedantic". Next followed Ravel's music for the opera L'heure espagnole (The Spanish Hour), full of humor and rich in color, employing a wide variety of instruments and their characteristic qualities, including the trombone, sarrusophone, tuba, celesta, xylophone, and bells. The libretto was by Franc - Nohain, after his own comedy of the same name.

Ravel further extended his mastery of impressionistic piano music with Gaspard de la nuit, based on a collection by the same name by Aloysius Bertrand, with some influence from the writings of Edgar Allan Poe, particularly in the second part. Viñes, as usual, performed the premiere but his performance displeased Ravel, and their relationship became strained from then on. For future premieres, Ravel replaced Viñes with Marguerite Long. Also unhappy with the conservative musical establishment which was discouraging performance of new music, around this time Ravel, Fauré, and some of his pupils formed the Société musicale indépendante (SMI). In 1910, the society presented the premiere of Ravel’s Ma mère l'oye (Mother Goose) in its original piano duet version. With this work, Ravel followed in the tradition of Schumann, Mussorgsky and Debussy, who also created memorable works of childhood themes. In 1912, Ravel's Ma mère l'oye was performed as a ballet (with added music) after being first transcribed from piano to orchestra. Looking to expand his contacts and career, Ravel made his first foreign tours to England and Scotland during 1909 and 1911.

Ravel began work with impresario Sergei Diaghilev during 1909 for the ballet Daphnis et Chloé commissioned by Diaghilev with the lead danced by the famous ballet dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky. Diaghilev had taken Paris by storm the previous year in his Parisian opera debut, Boris Godunov. Daphnis et Chloé took three years to complete, with conflicts constantly arising among the principal artists, including Léon Bakst (sets and costumes), Michel Fokine (libretto), and Ravel (music). In

frustration, Diaghilev nearly cancelled the project. The ballet had an

unenthusiastic reception and lasted only two performances, only to be

revived to acclaim a year later. Igor Stravinsky called Daphnis et Chloé "one

of the most beautiful products of all French music" and author Burnett

James claims that it is "Ravel's most impressive single achievement, as

it is his most opulent and confident orchestral score". The work is notable for its rhythmic diversity, lyricism, and evocations of nature. The score utilizes a large orchestra and two choruses, one onstage and one offstage. So exhausting was the effort to score the ballet that Ravel's health deteriorated, with a diagnosis of neurasthenia soon forcing him to rest for several months. During 1914, just as World War I began, Ravel composed his Piano Trio (for

piano, violin, and cello) with its Basque themes. The piece, difficult

to play well, is considered a masterpiece among trio works.

Although he considered his small stature and light weight an advantage to becoming an aviator, and he tried every means of securing service as a flyer, during the First World War Ravel was not allowed to enlist as a pilot because of his age and weak health. Instead, he became a truck driver stationed at the Verdun front. At one point Ravel's unit engaged a German unit that included a young Adolf Hitler. With his mother’s death in 1917, his fondest relationship ended and he fell into a “horrible despair”, adding to his ill health and the general gloom over the suffering endured by the people of his country during the war. However, during the war years, Ravel did manage some compositions, including one of his most popular works, Le tombeau de Couperin, a commemoration of the musical ideals of François Couperin, the early 18th century composer, which premiered in 1919. Each movement is dedicated to a friend of Ravel's who died in the war, with the final movement dedicated to the deceased husband of Ravel’s favorite pianist Marguerite Long. During the war, the Ligue Nationale pour la Defense de la Musique Française (National League for the Defense of French Music) was formed but Ravel, despite his strong antipathy for the German aggression, declined to join stating:

“it would be dangerous for French composers to ignore systematically the works of their foreign colleagues, and thus form themselves into a sort of national coterie: our musical art, so rich at the present time, would soon degenerate and become isolated by its own academic formulas.”

Ravel

was exhausted and lacking creative spirit at the war’s end in 1918.

With the death of Debussy and the emergence of Satie, Schoenberg and

Stravinsky, modern classical music had a new style to which Ravel would

shortly re-group and make his contribution.

Around 1920, Diaghilev commissioned Ravel to write La valse (The Waltz), originally named Wien (Vienna), which was to be used for a projected ballet. The piece, conceived many years earlier, became a waltz with a macabre undertone, famous for its “fantastic and fatal whirling”. However, it was rejected by Diaghilev as “not a ballet. It’s a portrait of ballet”. Ravel, hurt by the comment, ended the relationship. Subsequently, it became a popular concert work and when the two men met again in 1925, Ravel refused to shake Diaghilev's hand. Diaghilev challenged Ravel to a duel, but friends persuaded Diaghilev to recant. The two never met again.

In 1920, the French government awarded Ravel the Légion d'honneur, but he refused it. The next year, he retired to the French countryside where he continued to write music, albeit even less prolifically, but in more tranquil surroundings. He returned regularly to Paris for performances and socializing, and increased his foreign concert tours. Ravel maintained his influential participation with the SMI which continued its active role of promoting new music, particularly of British and American composers such as Arnold Bax, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Aaron Copland, and Virgil Thomson. With Debussy’s death, Ravel became perceived popularly as the main composer of French classical music. As Fauré stated in a letter to Ravel in October 1922, “I am happier than you can imagine about the solid position which you occupy and which you have acquired so brilliantly and so rapidly. It is a source of joy and pride for your old professor.” In 1922, Ravel completed his Sonata for Violin and Cello. Dedicated to Debussy’s memory, the work features the thinner texture popular with the younger postwar composers.

The English, in particular, lauded Ravel, as The Times reported April 16, 1923, “Since the death of Debussy, he has represented to English musicians the most vigorous current in modern French music." In reality, however, Ravel’s own music was no longer considered au courant in France. Satie had become the inspiring force for the new generation of French composers known as Les Six. Ravel was fully aware of this, and was mostly effective in preventing a serious breach between his generation of musicians and the younger group.

In post war Paris, American musical influence was strong. Jazz particularly was played in the cafes and became popular, and French composers including Ravel and Darius Milhaud were applying jazz elements to their work. Also in vogue was a return to simplicity in orchestration and a transition from the great scale of the works of Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss. Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev were in the ascendant, and Arnold Schoenberg's experiments were leading music into atonality. These trends posed challenges for Ravel, always a slow and deliberate composer, who desired to keep his music relevant but still revered the past. This may have played a part in his declining output and longer composing time during the 1920s.

Around 1922, Ravel completed his famous orchestral arrangement of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky, which through its widespread popularity brought Ravel great fame and substantial profit. The first half of the 1920s was a particularly lean period for composing but Ravel did complete successful concert tours to Amsterdam, Milan, London, Madrid, and Vienna, which also boosted his fame. By 1925, by virtue of the unwelcomed pressure of a performance deadline, he finally finished his opera L'enfant et les sortilèges, with its significant jazz and ragtime accents. Famed writer Colette provided the libretto. Around this time, he also completed Chansons madécasses, the summit of his vocal art.

In 1927, Ravel’s String Quartet received its first complete recording. By this time Ravel, like Edward Elgar, had become convinced of the importance of recording his works, especially with his input and direction. He made recordings nearly every year from then until his death. That same year, he completed and premiered his Sonata for Violin and Piano, his last chamber work, with its second movement (titled “Blues”) gaining much attention.

Ravel also served as a juror with Florence Meyer Blumenthal in awarding the Prix Blumenthal, a grant given between 1919 and 1954 to young French painters, sculptors, decorators, engravers, writers and musicians.

After two months of planning, in 1928 Ravel made a four month concert tour in North America, for a promised minimum of $10,000 (approximately $128,226, adjusted for inflation). In New York City, he received a standing ovation, unlike any of his unenthusiastic premieres in Paris. His all - Ravel concert in Boston was equally acclaimed. The noted critic Olin Downes wrote, “Mr. Ravel has pursued his way as an artist quietly and very well. He has disdained superficial or meretricious effects. He has been his own most unsparing critic.” Ravel conducted most of the leading orchestras in the U.S. from coast to coast and visited twenty - five cities.

He also met the American composer George Gershwin in New York and went with him to hear jazz in Harlem, probably hearing some of the famous jazz musicians such as Duke Ellington. There is a story that when Gershwin met Ravel, he mentioned that he would like to study with the French composer. According to Gershwin, the Frenchman retorted, "Why do you want to become a second - rate Ravel when you are already a first - rate Gershwin?" The second part of the story has Ravel asking Gershwin how much money he made. Upon hearing Gershwin's reply, Ravel suggested that maybe he should study with Gershwin. This tale may well be apocryphal: Gershwin seems also to have told a near identical story about a conversation with Arnold Schoenberg, and some have claimed it was with Igor Stravinsky. In any event, this had to have been before Ravel wrote Boléro, which became financially very successful for him.

Ravel then visited New Orleans and imbibed the jazz scene there as well. His admiration of jazz,

increased by his American visit, caused him to include some jazz

elements in a few of his later compositions, especially the two piano concertos. The great success of his American tour made Ravel famous internationally.

After returning to France, Ravel composed his most famous and controversial orchestral work Boléro, originally called Fandango. Ravel called it “an experiment in a very special and limited direction”. He stated his idea for the piece, “I am going to try to repeat it a number of times on different orchestral levels but without any development.” He conceived of it as an accompaniment to a ballet and not as an orchestral piece as, in his own opinion, “it has no music in it”, and was somewhat taken aback by its popular success. A public dispute began with conductor Arturo Toscanini. The Italian maestro, taking liberties with Ravel’s strict instructions, conducted the piece at a faster tempo and with an “accelerando at the finish”. Ravel insisted “I don’t ask for my music to be interpreted, but only that it should be played.” In the end, the feuding only helped to increase the work’s fame. A Hollywood film titled Bolero (1934), starring Carole Lombard and George Raft, made major use of the theme. Ravel made one of the few recordings of his own music when he conducted his Boléro with the Lamoureux Orchestra in 1930.

Remarkably, Ravel composed both of his piano concertos simultaneously. He completed the Concerto for the Left Hand first. The work was commissioned by Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had lost his right arm during World War I. Ravel was inspired by the technical challenges of the project. As Ravel stated, “In a work of this kind, it is essential to give the impression of a texture no thinner than that of a part written for both hands.” At the premiere of the work, Ravel, not proficient enough to perform the work with only his left hand, played two - handed and Wittgenstein was reportedly underwhelmed by it. But later Wittgenstein stated, “Only much later, after I’d studied the concerto for months, did I become fascinated by it and realized what a great work it was.” In 1933, Wittgenstein played the work in concert for the first time to instant acclaim. Critic Henry Prunières wrote, “From the opening measures, we are plunged into a world in which Ravel has but rarely introduced us.”

The other piano concerto was completed a year later. Its lighter tone follows the models of Mozart, Domenico Scarlatti, and Saint - Saëns, and also makes use of jazz like themes. Ravel dedicated the work to his favorite pianist, Marguerite Long, who played it and popularized it across Europe in over twenty cities, and they recorded it together in 1932. EMI later reissued the 1932 recording on LP and CD. Although Ravel was listed as the conductor on the original 78 rpm discs, it is possible he merely supervised the recording.

Ravel,

ever modest, was bemused by the critics' sudden favor of him since his

American tour: “Didn’t I represent to the critics for a long time the

most perfect example of insensitivity and lack of emotion?... And the

successes they have given me in the past few years are just as

unimportant.”

In 1932, Ravel suffered a major blow to the head in a taxi accident. This injury was not considered serious at the time. However, afterwards he began to experience aphasia like symptoms and was frequently absent minded. He had begun work on music for a film, Adventures of Don Quixote (1933) from Miguel de Cervantes's celebrated novel, featuring the Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin and directed by G.W. Pabst. When Ravel became unable to compose, and could not write down the musical ideas he heard in his mind, Pabst hired Jacques Ibert. However, three songs for baritone and orchestra that Ravel composed for the film were later published under the title Don Quichotte a Dulcinée, and have been performed and recorded.

On April 8, 2008, the New York Times published an article suggesting Ravel may have been in the early stages of frontotemporal dementia during 1928, and this might account for the repetitive nature of Boléro. This accords with an earlier article, published in a journal of neurology, that closely examines Ravel's clinical history and argues that his works Boléro and Piano Concerto for the Left Hand both indicate the impacts of neurological disease. This is contradicted somewhat, however, by the earlier cited comments by Ravel about how he created the deliberately repetitious theme for Boléro.

In late 1937, Ravel consented to experimental brain surgery, evidently with some hesitation. On December 17, he entered a hospital in Paris, following the advice of the well known neurosurgeon Clovis Vincent. Vincent assumed there was brain tumor, and on December 19 operated on Ravel. No tumor was found, but there was some shrinkage of the left hemisphere of his brain, which was re - inflated with serous fluid. When Ravel awoke from the anaesthesia, he asked for his brother, but quickly sank into a deep coma, from which he never awoke. He died on December 28, at the age of 62, in Paris.

Ravel death was probably a result of the brain surgery, with the underlying cause arguably being a brain injury caused by the automobile accident in 1932, and not from a brain tumor as some believe. This confusion may arise because his friend George Gershwin had died from a brain tumor only five months earlier.

On December 30, 1937, Ravel was buried next to his parents in a granite tomb at the cemetery at Levallois - Perret, a suburb of northwest Paris.

Ravel is not known to have had any intimate relationships, and his personal life, and especially his sexuality, remains a mystery. Ravel made a remark at one time suggesting that because he was such a perfectionist composer, so devoted to his work, he could never have a lasting intimate relationship with anyone. However, according to close friend and student Manuel Rosenthal, he asked violinist Hélène Jourdan - Mourhange to marry him, although she dismissed him, saying 'No, Maurice, I'm extremely fond of you, as you know, but only as a friend, and I couldn't possibly consider marrying you.' He is quoted as saying "The only love affair I have ever had was with music". Some of his friends suggested that Ravel frequented the bordellos of Paris, but no factual evidence has ever been found to substantiate this rumor.

A

recent hypothesis presented by David Lamaze, a composition teacher at

the Conservatoire de Rennes in France, is that he hid in his music representations of the nickname and the name of Misia Godebska,

transcribed into two groups of notes, Godebska = G D E B A and Misia =

Mi + Si + A = E B A. He was invited onto her boat during a 1905 cruise

on the Rhine after his failure at the Prix de Rome, for which her husband, Alfred Edwards, organized a scandal in the newspapers. This same man owned the Casino de Paris where the Ravel family had a number staged, Tourbillon de la mort (A

Car Somersault). The family of her half - brother, Cipa Godebski, is said

to have been like a second family for Ravel. In 1907 on Misia's boat L'Aimée, Ravel completed L'heure espagnole and the Rapsodie espagnole, and at the premiere of Daphnis et Chloé, Ravel arrived late and did not go to his box but to Misia's, where he offered her a Japanese doll. In her memoirs, Misia hid all these facts.

Active during a period of great artistic innovations and diversification, Ravel benefited from many sources and influences, though his music defies any facile classification. As Vladimir Jankélévitch notes in his biography, "no influence can claim to have conquered him entirely […]. Ravel remains ungraspable behind all these masks which the snobbery of the century has attempted to impose."

Ravel's musical language was ultimately very original, neither absolutely modernist nor impressionist. Like Debussy, Ravel categorically refused this description of “impressionist” which he believed was reserved exclusively for painting.

Ravel was a remarkable synthesist of disparate styles. His music matured early into his innovative and distinct style. As a student, he studied the scores of composers of the past methodically: as he stated, "in order to know one's own craft, one must study the craft of others." Though he liked the new French music, during his youth Ravel still felt fond of the older French styles of Franck and the Romanticism of Beethoven and Wagner. Or, as Viñes put it, discussing Ravel's aesthetics (not his religion):

"He is, moreover, very complicated, there being in him a mixture of Middle Ages Catholicism and satanic impiety, but also a love of Art and Beauty which guide him and which make him react candidly."

Certain aspects of his music can be considered to belong to the tradition of 18th century French classicism beginning with Couperin and Rameau as in Le Tombeau de Couperin. The uniquely 19th century French sensibilities of Fauré and Chabrier are reflected in Sérénade grotesque, Pavane pour une infante défunte, and Menuet antique, while pieces such as Jeux d'eau, and the String Quartet in F owe something to the innovations of Satie and Debussy. The virtuosity and poetry of Gaspard de la nuit and Concerto for the left handhint at Liszt and Chopin. His admiration for American jazz is echoed in L'enfant et les sortilèges, the Violin Sonata and the Piano Concerto in G, while the Russian school of music inspired homage in "À la manière de Borodin" and the orchestration of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition. Additionally, he variously cited Mozart, Saint - Saëns, Schubert and Schoenberg as inspirations for various pieces.

Ravel's music was innovative, though he did not follow the contemporary trend towards atonality, as pioneered by Schoenberg. Instead, he applied the aesthetics of the new French school of Chabrier, Satie, and particularly Debussy. Ravel's compositions rely upon modal melodies instead of using the major or minor scales for their predominant harmonic language. He preferred modes with major or minor flavors; for example, the Mixolydian instead of the major scale, and the Aeolian instead of the harmonic minor. As a result, there are virtually no leading tones in his output. Melodically, he tended to favor two modes: the Dorian and the Phrygian. Following the teachings of Gédalge, Ravel placed high importance on melody, once stating to Vaughan Williams, that there is "an implied melodic outline in all vital music."

In no way dependent on exclusively traditional modal practices, Ravel used extended harmonies and intricate modulations. He was fond of chords of the ninth and eleventh, and his characteristic harmonies are largely the result of a fondness for unresolved appoggiaturas, such as in the Valses nobles et sentimentales. He was inspired by various dances, his favorite being the minuet, composing the Menuet sur le nom d'Haydn in 1908, to commemorate the centenary of the death of Joseph Haydn. Other forms from which Ravel drew material include the forlane, rigaudon, waltz, czardas, habanera, passacaglia and the boléro.

He believed that composers should be aware of both individual and national consciousness. For him, Basque music was influential. He intended to write an earlier concerto, Zazpiak Bat, but it was never finished. The title is a result of his Basque heritage: meaning 'The Seven Are One', it refers to the seven Basque regions, and was a motto often used in association with the idea of a Basque nation. Instead, Ravel abandoned the piece, using its nationalistic themes and rhythms in some of his other pieces. Ravel also used other folk themes including Hebraic, Greek and Hungarian.

Ravel has almost always been considered one of the two great French impressionist composers, the other being Debussy. In reality Ravel was much more than an Impressionist (and in fact he resented being labelled as such). For example, he made extensive use of rollicking jazz tunes in his Piano Concerto in G Major in the first and third movements. Ravel also imitates Paganini's and Liszt's virtuoso gypsy themes and technique in Tzigane. In his À la manière de... Borodine (In the manner of... Borodin), Ravel plays with the ability to both mimic and remain original. In a more complex situation, A la maniere de... Emmanuel Chabrier / Paraphrase sur un air de Gounod ("Faust IIème acte"), Ravel takes on a theme from Gounod's Faust and arranges it in the style of Chabrier. He also composed short pieces in the manner of Haydn and his teacher Fauré. Even in writing in the style of others, Ravel's own voice as a composer remained distinct.

Ravel considered himself in many ways a classicist. He often relied on traditional forms, such as the ternary form, as well as traditional structures as ways of presenting his new melodic and rhythmic content, and his innovative harmonies. Ravel stated, "If I were called upon to do so, I would ask to be allowed to identify myself with the simple pronouncements made by Mozart ... He confined himself to saying that there is nothing that music cannot undertake to do, or dare, or portray, provided it continues to charm and always remain music." He often masked the sections of his structure with transitions that disguised the beginnings of the motif. This is apparent in his Valses nobles et sentimentales – inspired by Franz Schubert's collections, Valses nobles and Valses sentimentales – where the seven movements begin and end without pause, and in his chamber music where many movements are in sonata - allegro form, hiding the change from developmental sections to recapitulation.

From his own experience, Ravel was cognizant of the effect of new music on the ears of the public and he insightfully wrote:

On the initial performance of a new musical composition, the first impression of the public is generally one of reaction to the more superficial elements of its music, that is to say, to its external manifestations rather than to its inner content… often it is not until years after, when the means of expression have finally surrendered all their secrets, that the real inner emotion of the music becomes apparent to the listener.

His own composing method was craftsman like and perfectionistic. Igor Stravinsky once referred to Ravel as "the most perfect of Swiss watchmakers", a reference to the intricacy and precision of Ravel's works. Ravel, who sometimes spent years refining a piece, said, “My objective, therefore, is technical perfection. I can strive unceasingly to this end, since I am certain of never being able to attain it. The important thing is to get nearer to it all the time.”

More specifically he stated:

”In my own compositions I judge a long period of conscious gestation necessary. During this interval I come progressively, and with growing precision, to see the form and the evolution that the final work will take in its tonality. Thus I can be occupied for several years without writing a single note of the work, after which composition goes relatively quickly. But one must spend much time in eliminating all that could be regarded as superfluous in order to realize as completely as possible the definitive clarity so much desired. The moment arrives when new conceptions must be formulated for the final composition, but they cannot be artificially forced for they come only of their own accord, often deriving their original from some far-off perception and only manifesting themselves after long years.”

Many of his most innovative compositions were developed first as piano music. Ravel used this miniaturist approach to build up his architecture with many finely wrought strokes. To fill the requirements of larger works, he multiplied the number of small building blocks. This demonstrates the great regard he had for the piano traditions of Couperin, Scarlatti, Mozart, Chopin and Liszt. For example, Gaspard de la nuit can be viewed as an extension of Liszt’s virtuosity and advanced harmonics. Even Ravel’s most difficult pieces, however, are marked by elegance and refinement. Walter Gieseking found some of Ravel’s piano works to be among the most difficult pieces for the instrument but always based on “musically perfectly logical concepts”; not just technically demanding but also requiring the right expression.

Ravel’s great regard as an orchestrator is also based on his thorough methods. He usually notated the string parts first and insisted that the string section “sound perfectly in and of itself”. In writing for the other sections, he often preferred to score in tutti to produce a full, clear resonance. To add surprise and added color, the melody might start with one instrument and be continued with another.

Because of his perfectionism and methods, Ravel’s musical output over four decades is quite small. Most of his works were thought out over considerable lengths of time, then notated quickly, and refined painstakingly. When a piece would not progress, he would abandon a piece until inspired anew. There are only about sixty compositions in all, of which slightly more than half are instrumental. Ravel’s body of work includes pieces for piano, chamber works, two piano concerti, ballet music, opera, and song cycles. Though wide ranging in his music, Ravel avoided the symphonic form as well as religious themes and forms.

Ravel crafted his manuscripts meticulously, and relentlessly polished and corrected them. He destroyed hundreds of sketches and even re-copied entire autographs to correct one mistake. Early printed editions of his works were prone to errors so he worked painstakingly with his publisher, Durand, to correct them.

Though a competent pianist, Ravel decided early on to have virtuosi, like Ricardo Viñes, premiere and perform his work. As his career evolved, however, Ravel was again called upon to play his own piano music, and to conduct his larger works, particularly during a tour, both of which he considered chores in the same mold as "circus performances". Only rarely did he conduct works of other composers. One London critic stated "His baton is not the magician's wand of a virtuoso conductor. He just stood there beating time and keeping watch." As to how his music was to be played, Ravel was always clear and direct with his instructions.

Ravel was and is a leading figure in the art of transcription and orchestration.

During his life Ravel studied the ability of each orchestral instrument

carefully in order to determine its possible effects while being

sensitive to individual color and timbre. Ravel

regarded orchestration as a task separate from composition, involving

distinct technical skills. He was always careful to ensure that the

writing for each family of instruments worked in isolation as well as in

the complete ensemble. While he disapproved of tampering with his own

works once completed, orchestration gave him the opportunity to view

works in a different context. Among the most famous of his orchestral transcriptions is his own Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917)

of which he orchestrated the Prelude, Forlane, Minuet, and Rigaudon

movements in 1919. The orchestral version clarifies the harmonic

language of the suite and brings sharpness to its classical dance

rhythms. Modest Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition is best known through its orchestration by Ravel. In this version, produced in 1922, Ravel omits the Promenade between "Samuel" Goldenberg und "Schmuÿle" and Limoges and

applies artistic license to some particulars of dynamics and notation

as well as putting forth the virtuoso effort of a master colourist

throughout.

Ravel was always a supporter of young musicians, through his society and associations and through his personal individual advice and his help in securing performance dates. His closest students included Maurice Delage, Manuel Rosenthal, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Alexis Roland - Manuel and Vlado Perlemuter. Ravel modeled his teaching methods after his own teacher Gabriel Fauré, avoiding formulas and emphasizing individualism. Ravel's preferred way of teaching would be to have a conversation with his students and demonstrate his points at the piano. He was rigorous and demanding in teaching counterpoint and fugue, as he revered Johann Sebastian Bach without reservation. But in all other areas, he considered Mozart the ideal, with the perfect balance between "classical symmetry and the element of surprise", and with works of clarity, perfect craftsmanship, and measured amounts of lyricism. Often Ravel would challenge a student with "What would Mozart do?" and then ask the student to invent his own solution.

Though never a paid critic as Debussy had been, Ravel had strong opinions on historical and contemporary music and musicians, which influenced his younger contemporaries. In creating his own music, he tended to avoid the more monumental composers as models, finding relatively little kinship with or inspiration from Beethoven, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Hector Berlioz, or Franck. However, as an outspoken commentator on the Romantic giants, he found much of Beethoven "exasperating", Wagner's influence "pernicious" and Berlioz's harmony "clumsy". He had considerable admiration for other 19th century masters such as Chopin, Liszt, Mendelssohn, and Schubert. Despite what he considered its technical deficiencies, Ravel was a strong advocate of Russian music and praised its spontaneity, orchestral color, and exoticism.