<Back to Index>

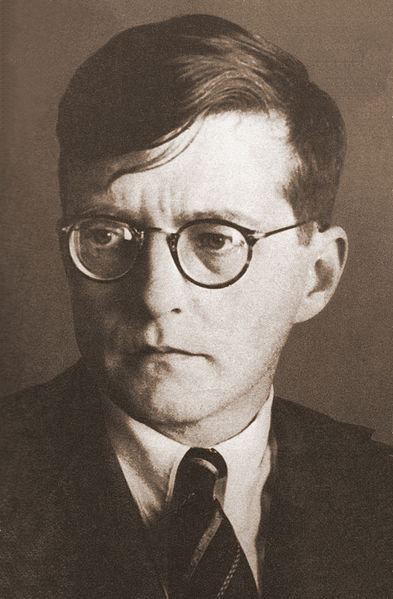

- Composer Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, 1906

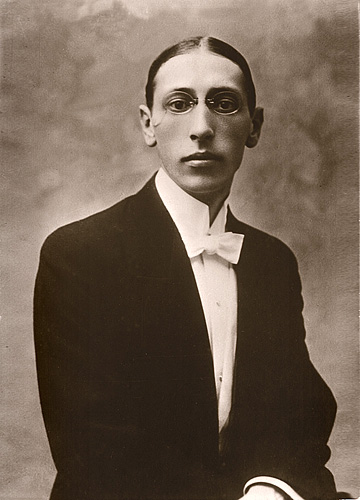

- Composer Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky, 1882

PAGE SPONSOR

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich (Russian: Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович; 25 September 1906 – 9 August 1975) was a Soviet Russian composer as well as a pianist and was one of the most celebrated composers of the 20th century.

Shostakovich achieved fame in the Soviet Union under the patronage of Leon Trotsky's chief of staff Mikhail Tukhachevsky, but later had a complex and difficult relationship with the government. Nevertheless, he also received accolades and state awards and served in the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR (1947 – 1962) and the USSR (from 1962 until death).

After a period influenced by Sergei Prokofiev and Igor Stravinsky, Shostakovich developed a hybrid style, as exemplified by Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District (1934). This single work juxtaposed a wide variety of trends, including the neo - classical style (showing the influence of Stravinsky) and post - Romanticism (after Gustav Mahler). Sharp contrasts and elements of the grotesque characterize much of his music.

Shostakovich's orchestral works include 15 symphonies and six concerti. Music for chamber ensembles includes 15 string quartets,

a piano quintet, two pieces for a string octet, and two piano trios.

For the piano he composed two solo sonatas, an early set of preludes, and a later set of 24 preludes and fugues. Other works include three operas, and a substantial quantity of film music.

Born at 2 Podolskaya Ulitsa in Saint Petersburg, Russia, Shostakovich was the second of three children born to Dmitri Boleslavovich Shostakovich and Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina. Shostakovich's paternal grandfather (originally surnamed Szostakowicz) was of Polish Roman Catholic descent (his family roots trace to the region of the town of Vileyka in Belarus), but his immediate forebears came from Siberia. His paternal grandfather, a Polish revolutionary in the January Uprising of 1863–4, had been exiled to Narim (near Tomsk) in 1866 in the crackdown that followed Dmitri Karakozov's assassination attempt on Tsar Alexander II. When his term of exile ended, Boleslaw Szostakowicz decided to remain in Siberia. He eventually became a successful banker in Irkutsk and raised a large family. His son, Dmitriy Boleslavovich Shostakovich, the composer's father, was born in exile in Narim in 1875 and attended Saint Petersburg University, graduating in 1899 from the faculty of physics and mathematics. After graduation, Dmitriy Boleslavovich went to work as an engineer under Dmitriy Mendeleyev at the Bureau of Weights and Measures in Saint Petersburg. In 1903, he married Sofiya Vasilievna Kokoulina, another Siberian transplant to the capital. Sofiya herself was one of six children born to Vasiliy Yakovlevich Kokoulin, a Russian Siberian native.

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was a child prodigy as a pianist and composer, his talent becoming apparent after he began piano lessons with his mother at the age of nine. (On several occasions, he displayed a remarkable ability to remember what his mother had played at the previous lesson, and would get "caught in the act" of pretending to read, playing the previous lesson's music when different music was placed in front of him.) In 1918, he wrote a funeral march in memory of two leaders of the Kadet party, murdered by Bolshevik sailors.

In 1919, at the age of 13, he was allowed to enter the Petrograd Conservatory, then headed by Alexander Glazunov. Glazunov monitored Shostakovich's progress closely and promoted him. Shostakovich studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev, after a year in the class of Elena Rozanova, composition with Maximilian Steinberg, and counterpoint and fugue with Nikolay Sokolov, with whom he became friends. Shostakovich also attended Alexander Ossovsky's history of music classes. However, he suffered for his perceived lack of political zeal, and initially failed his exam in Marxist methodology in 1926. His first major musical achievement was the First Symphony (premiered 1926), written as his graduation piece at the age of nineteen.

After graduation, Shostakovich initially embarked on a dual career as concert pianist and composer, but his dry style of playing (his American biographer, Laurel Fay, comments on his "emotional restraint" and "riveting rhythmic drive") was often unappreciated. He nevertheless won an "honorable mention" at the First International Frederic Chopin Piano Competition in Warsaw in 1927. After the competition Shostakovich met the conductor Bruno Walter, who was so impressed by the composer's First Symphony that he conducted it at its Berlin premiere later that year. Leopold Stokowski was equally impressed and gave the work its U.S. premiere the following year in Philadelphia and also made the work's first recording.

Thereafter, Shostakovich concentrated on composition, and soon limited his performances primarily to those of his own works. In 1927 he wrote his Second Symphony (subtitled To October), a patriotic piece with a great pro - Soviet choral finale. Due to its experimental nature, as with the subsequent Third Symphony, the pieces were not critically acclaimed with the enthusiasm as granted to the First.

1927 also marked the beginning of Shostakovich's relationship with Ivan Sollertinsky, who remained his closest friend until the latter's death in 1944. Sollertinsky introduced the composer to the music of Gustav Mahler, which had a strong influence on his music from the Fourth Symphony onwards.

While writing the Second Symphony, Shostakovich also began work on his satirical opera The Nose, based on the story by Gogol. In June 1929, the opera was given a concert performance, against Shostakovich's own wishes, and was ferociously attacked by the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians (RAPM). Its stage premiere on 18 January 1930 opened to generally poor reviews and widespread incomprehension amongst musicians.

Shostakovich composed his first film score for the 1929 silent movie, The New Babylon, set during the 1871 Paris Commune.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Shostakovich worked at TRAM, a proletarian youth theater. Although he did little work in this post, it shielded him from ideological attack. Much of this period was spent writing his opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District, which was first performed in 1934. It was immediately successful, on both popular and official levels. It was described as "the result of the general success of Socialist construction, of the correct policy of the Party", and as an opera that “could have been written only by a Soviet composer brought up in the best tradition of Soviet culture.”

Shostakovich

married his first wife, Nina Varzar, in 1932. Initial difficulties led

to a divorce in 1935, but the couple soon remarried when Nina became pregnant with their first child.

In 1936, Shostakovich fell from official favor. The year began with a series of attacks on him in Pravda, in particular an article entitled, "Muddle Instead of Music". Shostakovich was away on a concert tour in Arkhangel’sk when he heard news of the first Pravda article. Two days before the article was published on the evening of 28 January, a friend had advised Shostakovich to attend the Bolshoi Theater production of Lady Macbeth. When he arrived, he saw that Stalin and the Politburo were there. In letters written to Ivan Sollertinsky, a close friend and advisor, Shostakovich recounted the horror with which he watched as Stalin shuddered every time the brass and percussion played too loudly. Equally horrifying was the way Stalin and his companions laughed at the love making scene between Sergei and Katerina. Eyewitness accounts testify that Shostakovich was “white as a sheet” when he went to take his bow after the third act.

The article, which condemned Lady Macbeth as formalist, "coarse, primitive and vulgar," was thought to have been instigated by Stalin. Consequently, commissions began to fall off, and his income fell by about three quarters. Even Soviet music critics who had praised the opera were forced to recant in print, saying they "failed to detect the shortcomings of Lady Macbeth as pointed out by the Pravda". Shortly after the “Muddle Instead of Music” article, Pravda published another, “Ballet Falsehood,” that criticized Shostakovich’s ballet The Limpid Stream. Shostakovich did not expect this second article because the general public and press already accepted this music as “democratic" - that is, tuneful and accessible. However, Pravda criticized The Limpid Stream for incorrectly displaying peasant life on the collective farm.

More widely, 1936 marked the beginning of the Great Terror,

in which many of the composer's friends and relatives were imprisoned

or killed: these included his patron Marshal Tukhachevsky (shot months

after his arrest); his brother - in - law Vsevolod Frederiks (a distinguished physicist, eventually released but died before he got home); his close friend Nikolai Zhilyayev (a

musicologist who had taught Tukhachevsky; shot shortly after his

arrest); his mother - in - law, the astronomer Sofiya Mikhailovna Varzar

(sent to a camp in Karaganda); his friend, the Marxist writer Galina

Serbryakova (20 years in camps); his uncle, Maxim Kostrykin (died); and

his colleagues Boris Kornilov and Adrian Piotrovsky (executed). His only consolation in this period was the birth of his daughter Galina in 1936; his son Maxim was born two years later.

The publication of the Pravda editorials coincided with the composition of Shostakovich's Fourth Symphony. The work was a great shift in style for the composer, due to the substantial influence of Gustav Mahler, as well as multiple Western style elements. The symphony gave Shostakovich compositional trouble, as he attempted to reform his style into a new idiom. The composer was well into the work when the fatal articles appeared. Despite this, Shostakovich continued to compose the symphony and planned a premiere at the end of 1936. Rehearsals began that December, but after a number of rehearsals Shostakovich, for reasons still debated today, decided to withdraw the symphony from the public. A number of his friends and colleagues, such as Isaak Glikman, have suggested that it was in fact an official ban which Shostakovich was persuaded to present as a voluntary withdrawal. Whatever the case, it seems possible that this action saved the composer's life: during this time Shostakovich feared for himself and his family. Yet Shostakovich did not repudiate the work: it retained its designation as his Fourth Symphony. A piano reduction was published in 1946, and the work was finally premiered in 1961, well after Stalin's death.

During

the years of 1936 and 1937, in order to maintain as low a profile as

possible between the Fourth and Fifth symphonies, Shostakovich mainly composed film music, a genre favored by Stalin and lacking in dangerous personal expression.

The composer's response to his denunciation was the Fifth Symphony of 1937, which was musically more conservative than his earlier works. Premiering on 21 November 1937 in Leningrad, it was a phenomenal success: many in the Leningrad audience had lost family or friends to the mass executions. The Fifth drove many to tears and welling emotions. Later Shostakovich wrote in his memoirs: "I'll never believe that a man who understood nothing could feel the Fifth Symphony. Of course they understood, they understood what was happening around them and they understood what the Fifth was about."

The success put Shostakovich in good standing once again. Music critics and the authorities alike, including those who had earlier accused Shostakovich of formalism, claimed that he had learned from his mistakes and had become a true Soviet artist. The composer Dmitry Kabalevsky, who had been among those who disassociated himself from Shostakovich when the Pravda article was published, praised the Fifth Symphony and congratulated Shostakovich for “not having given into the seductive temptations of his previous ‘erroneous’ ways.”

It was also at this time that Shostakovich composed the first of his string quartets. His chamber works allowed him to experiment and express ideas which would have been unacceptable in his more public symphonic pieces. In September 1937, he began to teach composition at the Leningrad Conservatory, which provided some financial security but interfered with his own creative work.

In 1939, before the Soviet forces invaded Finland, the Party Secretary of Leningrad Andrei Zhdanov commissioned a celebratory piece from Shostakovich, entitled Suite on Finnish Themes to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army would be parading through the Finnish capital Helsinki. The Winter War was a humiliation for the Red Army, and Shostakovich would never lay claim to the authorship of this work. It was not performed until 2001.

After the outbreak of war between the Soviet Union and Germany in 1941, Shostakovich initially remained in Leningrad. He tried to enlist for the military but was turned away because he had bad eyesight. To compensate, Shostakovich became a volunteer for the Leningrad Conservatory’s firefighter brigade and delivered a radio broadcast to the Soviet people. The photograph for which he posed was published in newspapers throughout the country.

But his greatest and most famous wartime contribution was the Seventh Symphony. The composer wrote the first three movements in Leningrad and completed the work in Kuibyshev, now a settlement in Volgograd Oblast, where he and his family had been evacuated. Whether or not Shostakovich really conceived the idea of the symphony with the siege of Leningrad in mind, it was officially claimed as a representation of the people of Leningrad’s brave resistance to the German invaders and an authentic piece of patriotic art at a time when morale needed boosting. The symphony was first premiered at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow and was soon performed abroad in London and the United States. However, the most compelling performance was by the Radio Orchestra in besieged Leningrad. The orchestra only had fourteen musicians left, so the conductor Karl Eliasberg had to recruit anyone who could play a musical instrument to perform the symphony.

In spring 1943, the family moved to Moscow. At the time of the Eighth Symphony's premiere, the tide had turned for the Red Army. Therefore the public, and most importantly the authorities, wanted another triumphant piece from the composer. Instead, they got the Eighth Symphony, perhaps the ultimate in sombre and violent expression within Shostakovich's output. In order to preserve the image of Shostakovich (a vital bridge to the people of the Union and to the West), the government assigned the name "Stalingrad" to the symphony, giving it the appearance of a mourning of the dead in the bloody Battle of Stalingrad. However, the symphony did not escape criticism. Shostakovich is reported to have said: "When the Eighth was performed, it was openly declared counter - revolutionary and anti - Soviet. They said, 'Why did Shostakovich write an optimistic symphony at the beginning of the war and a tragic one now? At the beginning we were retreating and now we're attacking, destroying the Fascists. And Shostakovich is acting tragic, that means he's on the side of the fascists.'" The work was unofficially but effectively banned until 1956.

The Ninth Symphony (1945),

in contrast, is an ironic Haydnesque parody, which failed to satisfy

demands for a "hymn of victory." The war was won, and unfortunately

Shostakovich’s “pretty” symphony was interpreted as a mockery of the

Soviet Union’s victory rather than a celebratory piece. Shostakovich

continued to compose chamber music, notably his Second Piano Trio (Op. 67), dedicated to the memory of Sollertinsky, with a bitter - sweet, Jewish themed totentanz finale.

In 1948 Shostakovich, along with many other composers, was again denounced for formalism in the Zhdanov decree. Andrei Zhdanov, Chairman of the RSFSR Supreme Soviet, accused Shostakovich and other composers (such as Sergei Prokofiev and Aram Khachaturian) for writing inappropriate and formalist music. This was part of an ongoing anti - formalism campaign intended to root out all Western compositional influence as well as any perceived "non - Russian" output. The conference resulted in the publication of the Central Committee’s Decree “On V. Muradeli’s opera The Great Friendship,” which was targeted towards all Soviet composers and demanded that they only write “proletarian” music, or music for the masses. The accused composers, including Shostakovich, were summoned to make public apologies in front of the committee. Most of Shostakovich's works were banned, and his family had privileges withdrawn. Yuri Lyubimov says that at this time "he waited for his arrest at night out on the landing by the lift, so that at least his family wouldn't be disturbed."

The consequences of the decree for composers were harsh. Shostakovich was among those who were dismissed from the Conservatoire altogether. For Shostakovich, the loss of money was perhaps the largest blow. Others still in the Conservatory experienced an atmosphere that was thick with suspicion. No one wanted their work to be understood as formalist, so many resorted to accusing their colleagues of writing or performing anti - proletarian music.

In the next few years he composed three categories of work: film music to pay the rent, official works aimed at securing official rehabilitation, and serious works "for the desk drawer". The latter included the Violin Concerto No. 1 and the song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry. The cycle was written at a time when the post - war anti - Semitic campaign was already under way, with widespread arrests including of I. Dobrushin and Yiditsky, the compilers of the book from which Shostakovich took his texts.

The restrictions on Shostakovich's music and living arrangements were eased in 1949, when Stalin decided that the Soviets needed to send artistic representatives to the Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace in New York City, and that Shostakovich should be amongst them. For Shostakovich, it was a humiliating experience culminating in a New York press conference where he was expected to read a pre - prepared speech. Nicolas Nabokov, who was present in the audience, witnessed Shostakovich starting to read "in a nervous and shaky voice" before he had to break off "and the speech was continued in English by a suave radio baritone". Fully aware that Shostakovich was not free to speak his mind, Nabokov publicly asked the composer whether he supported the then recent denunciation of Stravinsky's music in the Soviet Union. Shostakovich, who was a great admirer of Stravinsky and had been influenced by his music, had no alternative but to answer in the affirmative. Nabokov did not hesitate to publish that this demonstrated that Shostakovich was "not a free man, but an obedient tool of his government." Shostakovich never forgave Nabokov for this public humiliation. That same year Shostakovich was obliged to compose the cantata Song of the Forests, which praised Stalin as the "great gardener." In 1951 the composer was made a deputy to the Supreme Soviet of RSFSR.

Stalin's death in 1953 was the biggest step towards Shostakovich's rehabilitation as a creative artist, which was marked by his Tenth Symphony. It features a number of musical quotations and codes (notably the DSCH and Elmira motifs, Elmira Nazirova being a pianist and composer who had studied under Shostakovich in the year prior to his dismissal from the Moscow Conservatoire), the meaning of which is still debated, whilst the savage second movement, according to Testimony, is intended as a musical portrait of Stalin himself. The Symphony ranks alongside the Fifth and Seventh as one of his most popular works. 1953 also saw a stream of premieres of the "desk drawer" works.

During the forties and fifties Shostakovich had close relationships with two of his pupils: Galina Ustvolskaya and Elmira Nazirova. In the background to all this remained Shostakovich's first, open marriage to Nina Varzar until her death in 1954. He taught Ustvolskaya from 1937 to 1947. The nature of their relationship is far from clear: Mstislav Rostropovich described it as "tender". Ustvolskaya rejected a proposal of marriage from him after Nina's death. Shostakovich's daughter, Galina, recalled her father consulting her and Maxim about the possibility of Ustvolskaya being their stepmother. Ustvolskaya's friend, Viktor Suslin, said that she had been "deeply disappointed" in Shostakovich by the time of her graduation in 1947. The relationship with Nazirova seems to have been one sided, expressed largely through his letters to her, and can be dated to around 1953 to 1956. He married his second wife, Komsomol activist Margarita Kainova, in 1956; the couple proved ill matched, and divorced three years later.

In 1954, Shostakovich wrote the Festive Overture, opus 96, that was used as the theme music for the 1980 Summer Olympics. In addition his '"Theme from the film Pirogov, Opus 76a: Finale" was played as the cauldron was lit at the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece.

In 1959, Shostakovich appeared on stage in Moscow at the end of a concert performance of his Fifth Symphony, congratulating Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for

their performance (part of a concert tour of the Soviet Union).

Bernstein recorded the symphony later that year in New York for Columbia Records.

The year 1960 marked another turning point in Shostakovich's life: his joining of the Communist Party. The government wanted to appoint him General Secretary of the Composer’s Union, but in order to hold that position Shostakovich was required to attain Party membership. It was understood that Nikita Khrushchev, the First Secretary of the Communist Party from 1958 to 1964, was looking for support from the leading ranks of the intelligentsia in an effort to create a better relationship with the Soviet Union’s artists. This event has been interpreted variously as a show of commitment, a mark of cowardice, the result of political pressure, and as his free decision. On the one hand, the apparat was undoubtedly less repressive than it had been before Stalin's death. On the other, his son recalled that the event reduced Shostakovich to tears, and he later told his wife Irina that he had been blackmailed. Lev Lebedinsky has said that the composer was suicidal. Once he joined the Party, several articles denouncing individualism in music were published in Pravda under his name, though he did not actually write them. In addition, in joining the party, Shostakovich was also committing himself to finally writing the homage to Lenin that he had promised before. His Twelfth Symphony, which portrays the Bolshevik Revolution and was completed in 1961, was dedicated to Vladimir Lenin and called “The Year 1917.” Around this time, his health also began to deteriorate.

Shostakovich's musical response to these personal crises was the Eighth String Quartet, composed in only three days. Shostakovich subtitled the piece, "To the victims of fascism and war", ostensibly in memory of the Dresden fire bombing that took place in 1945. Yet, like the Tenth Symphony, this quartet incorporates quotations from several of his past works and his musical monogram: Shostakovich confessed to Glikman, "I started thinking that if some day I die, nobody is likely to write a work in memory of me, so I had better write one myself." Several of Shostakovich's colleagues, including Natalya Vovsi - Mikhoels and the cellist Valentin Berlinsky were also aware of the Eighth Quartet's biographical intent.

In 1962 he married for the third time, to Irina Supinskaya. In a letter to his friend Isaak Glikman, he wrote, "her only defect is that she is 27 years old. In all other respects she is splendid: clever, cheerful, straightforward and very likeable." According to Galina Vishnevskaya, who knew the Shostakoviches well, this marriage was a very happy one: "It was with her that Dmitri Dmitriyevich finally came to know domestic peace... Surely, she prolonged his life by several years." In November Shostakovich made his only venture into conducting, conducting a couple of his own works in Gorky: otherwise he declined to conduct, citing nerves and ill health as his reasons.

That year saw Shostakovich again turn to the subject of anti - Semitism in his Thirteenth Symphony (subtitled Babi Yar). The symphony sets a number of poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko, the first of which commemorates a massacre of the Jews during the Second World War. Opinions are divided how great a risk this was: the poem had been published in Soviet media, and was not banned, but it remained controversial. After the symphony's premiere, Yevtushenko was forced to add a stanza to his poem which said that Russians and Ukrainians had died alongside the Jews at Babi Yar.

In 1965 Shostakovich raised his voice in defense of poet Joseph Brodsky,

who was sentenced to five years of exile and hard labor. Shostakovich

co-signed protests together with Yevtushenko and fellow Soviet artists Kornei Chukovsky, Anna Akhmatova, Samuil Marshak, and the French philosopher Jean - Paul Sartre.

After the protests the sentence was commuted, and Brodsky returned to

Leningrad. Shostakovich joined the group of 25 distinguished

intellectuals in signing the letter to Leonid Brezhnev asking not to rehabilitate Stalin.

In later life, Shostakovich suffered from chronic ill health, but he resisted giving up cigarettes and vodka. Beginning in 1958 he suffered from a debilitating condition that particularly affected his right hand, eventually forcing him to give up piano playing; in 1965 it was diagnosed as polio. He also suffered heart attacks the following year and again in 1971, and several falls in which he broke both his legs; in 1967 he wrote in a letter:

"Target achieved so far: 75% (right leg broken, left leg broken, right hand defective). All I need to do now is wreck the left hand and then 100% of my extremities will be out of order."

A preoccupation with his own mortality permeates Shostakovich's later works, among them the later quartets and the Fourteenth Symphony of 1969 (a song cycle based on a number of poems on the theme of death). This piece also finds Shostakovich at his most extreme with musical language, with twelve - tone themes and dense polyphony used throughout. Shostakovich dedicated this score to his close friend Benjamin Britten, who conducted its Western premiere at the 1970 Aldeburgh Festival. The Fifteenth Symphony of 1971 is, by contrast, melodic and retrospective in nature, quoting Wagner, Rossini and the composer's own Fourth Symphony.

Shostakovich died of lung cancer on 9 August 1975 and after a civic funeral was interred in the Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow. Even before his death he had been commemorated with the naming of the Shostakovich Peninsula on Alexander Island, Antarctica.

He was survived by his third wife, Irina; his daughter, Galina; and his son, Maxim, a pianist and conductor who was the dedicatee and first performer of some of his father's works. Shostakovich himself left behind several recordings of his own piano works, while other noted interpreters of his music include his friends Emil Gilels, Mstislav Rostropovich, Tatiana Nikolayeva, Maria Yudina, David Oistrakh, and members of the Beethoven Quartet.

Shostakovich's opera Orango (1932) was found by Russian researcher Olga Digonskaya in his last home. It is being orchestrated by the British composer Gerard McBurney and will be premiered in December 2011 by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Shostakovich's musical influence on later composers outside the former Soviet Union has been relatively slight, although Alfred Schnittke took up his eclecticism, and his contrasts between the dynamic and the static, and some of André Previn's

music shows clear links to Shostakovich's style of orchestration. His

influence can also be seen in some Nordic composers, such as Lars - Erik Larsson. Many of his Russian contemporaries, and his pupils at the Leningrad Conservatory, however, were strongly influenced by his style (including German Okunev, Boris Tishchenko, whose 5th Symphony of 1978 is dedicated to Shostakovich's memory, Sergei Slonimsky,

and others). Shostakovich's conservative idiom has nonetheless grown

increasingly popular with audiences both within and beyond Russia, as

the avant garde has declined in influence and debate about his political

views has developed.

Shostakovich's works are broadly tonal and in the Romantic tradition, but with elements of atonality and chromaticism. In some of his later works (e.g., the Twelfth Quartet), he made use of tone rows. His output is dominated by his cycles of symphonies and string quartets, each numbering fifteen. The symphonies are distributed fairly evenly throughout his career, while the quartets are concentrated towards the latter part. Among the most popular are the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies and the Eighth and Fifteenth Quartets. Other works include the operas Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, The Nose and the unfinished The Gamblers based on the comedy of Nikolai Gogol; six concertos (two each for piano, violin and cello); two piano trios; and a large quantity of film music.

Shostakovich's music shows the influence of many of the composers he most admired: Bach in his fugues and passacaglias; Beethoven in the late quartets; Mahler in the symphonies and Berg in his use of musical codes and quotations. Among Russian composers, he particularly admired Modest Mussorgsky, whose operas Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina he re-orchestrated; Mussorgsky's influence is most prominent in the wintry scenes of Lady Macbeth and the Eleventh Symphony, as well as in his satirical works such as "Rayok". Prokofiev's influence is most apparent in the earlier piano works, such as the first sonata and first concerto. The influence of Russian church and folk music is very evident in his works for unaccompanied choir of the 1950s.

Shostakovich's relationship with Stravinsky was profoundly ambivalent; as he wrote to Glikman, "Stravinsky the composer I worship. Stravinsky the thinker I despise." He was particularly enamored of the Symphony of Psalms, presenting a copy of his own piano version of it to Stravinsky when the latter visited the USSR in 1962. (The meeting of the two composers was not very successful, however; observers commented on Shostakovich's extreme nervousness and Stravinsky's "cruelty" to him.)

Many commentators have noted the disjunction between the experimental works before the 1936 denunciation and the more conservative ones that followed; the composer told Flora Litvinova, "without 'Party guidance' ... I would have displayed more brilliance, used more sarcasm, I could have revealed my ideas openly instead of having to resort to camouflage." Articles published by Shostakovich in 1934 and 1935 cited Berg, Schoenberg, Krenek, Hindemith, "and especially Stravinsky" among his influences. Key works of the earlier period are the First Symphony, which combined the academicism of the conservatory with his progressive inclinations; The Nose ("The most uncompromisingly modernist of all his stage - works"); Lady Macbeth. which precipitated the denunciation; and the Fourth Symphony, described by Grove as "a colossal synthesis of Shostakovich's musical development to date". The Fourth Symphony was also the first in which the influence of Mahler came to the fore, prefiguring the route Shostakovich was to take to secure his rehabilitation, while he himself admitted that the preceding two were his least successful.

In

the years after 1936, Shostakovich's symphonic works were outwardly

musically conservative, regardless of any subversive political content.

During this time he turned increasingly to chamber works, a field that permitted the composer to explore different and often darker ideas without inviting external scrutiny. While

his chamber works were largely tonal, they gave Shostakovich an outlet

for sombre reflection not welcomed in his more public works. This is

most apparent in the late chamber works, which portray what Groves has

described as a "world of purgatorial numbness"; in some of these he included the use of tone rows, although he treated these as melodic themes rather than serially. Vocal works are also a prominent feature of his late output, setting texts often concerned with love, death and art.

Even before the Stalinist anti - Semitic campaigns in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Shostakovich showed an interest in Jewish themes. He was intrigued by Jewish music’s “ability to build a jolly melody on sad intonations.” Examples of works that included Jewish themes are the Fourth String Quartet (1949), the First Violin Concerto (1948), and the Four Monologues on Pushkin Poems (1952). He was further inspired to write with Jewish themes when he examined Moiser Beregovsky’s thesis on the theme of Jewish folk music in 1946.

In 1948, Shostakovich acquired a book of Jewish folk songs, and from this he composed the song cycle From Jewish Poetry.

He initially wrote eight songs that were meant to represent the

hardships of being Jewish in the Soviet Union. However in order to

disguise this, Shostakovich ended up adding three more songs meant to

demonstrate the great life Jews had under the Soviet regime. Despite his

efforts to hide the real meaning in the work, the Union of Composers refused to approve his music in 1949 under the pressure of the anti - Semitism that gripped the country. From Jewish Poetry could not be performed until after Stalin’s death in March 1953, along with all the other works that were forbidden.

According to Shostakovich scholar Gerard McBurney, opinion is divided on whether his music is "of visionary power and originality, as some maintain, or, as others think, derivative, trashy, empty and second - hand." William Walton, his British contemporary, described him as "The greatest composer of the 20th century." Musicologist David Fanning concludes in Grove that, "Amid the conflicting pressures of official requirements, the mass suffering of his fellow countrymen, and his personal ideals of humanitarian and public service, he succeeded in forging a musical language of colossal emotional power."

Some modern composers have been critical. Pierre Boulez dismissed Shostakovich's music as "the second, or even third pressing of Mahler." The Romanian composer and Webern disciple Philip Gershkovich called Shostakovich "a hack in a trance." A related complaint is that Shostakovich's style is vulgar and strident: Stravinsky wrote of Lady Macbeth: "brutally hammering ... and monotonous." English composer and musicologist Robin Holloway described his music as "battleship - grey in melody and harmony, factory - functional in structure; in content all rhetoric and coercion."

In the 1980s, the Finnish conductor and composer Esa - Pekka Salonen was critical of Shostakovich and refused to conduct his music. For instance, he said in 1987:

"Shostakovich is in many ways a polar counter - force for Stravinsky. [...] When I have said that the 7th symphony of Shostakovich is a dull and unpleasant composition, people have responded: 'Yes, yes, but think of the background of that symphony.' Such an attitude does no good to anyone."

It is certainly true that Shostakovich borrows extensively from the material and styles both of earlier composers and of popular music; the vulgarity of "low" music is a notable influence on this "greatest of eclectics". McBurney traces this to the avant garde artistic circles of the early Soviet period in which Shostakovich moved early in his career, and argues that these borrowings were a deliberate technique to allow him to create "patterns of contrast, repetition, exaggeration" that gave his music the large scale structure it required.

Shostakovich's works have quite a few social justice themes. For example, in Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District,

the protagonist is doomed by the patriarchal society, and the opera

ends with her tragic death. Shostakovich had actually been brought up

with feminism; his godmother, Klavdia Lukashevich, was a feminist

activist and was also a powerful influence on the young Dmitri

Shostakovich.

Shostakovich was in many ways an obsessive man: according to his daughter he was "obsessed with cleanliness"; he synchronized the clocks in his apartment; he regularly sent cards to himself to test how well the postal service was working. Elizabeth Wilson's Shostakovich: A Life Remembered (1994 edition) indexes 26 references to his nervousness. Mikhail Druskin remembers that even as a young man the composer was "fragile and nervously agile". Yuri Lyubimov comments, "The fact that he was more vulnerable and receptive than other people was no doubt an important feature of his genius". In later life, Krzysztof Meyerre called, "his face was a bag of tics and grimaces".

In his lighter moods, sport was one of his main recreations, although he preferred spectating or umpiring to participating (he was a qualified football referee). His favorite football club was Zenit Leningrad, which he would watch regularly. He also enjoyed playing card games, particularly patience. Both light and dark sides of his character were evident in his fondness for satirical writers such as Gogol, Chekhov and Mikhail Zoshchenko. The influence of the latter in particular is evident in his letters, which include wry parodies of Soviet officialese. Zoshchenko himself noted the contradictions in the composer's character: "he is ... frail, fragile, withdrawn, an infinitely direct, pure child ... [but he is also] hard, acid, extremely intelligent, strong perhaps, despotic and not altogether good - natured (although cerebrally good - natured)".

He was diffident by nature: Flora Litvinova has said he was "completely incapable of saying 'No' to anybody." This meant he was easily persuaded to sign official statements, including a denunciation of Andrei Sakharov in

1973; on the other hand he was willing to try to help constituents in

his capacities as chairman of the Composers' Union and Deputy to the

Supreme Soviet. Oleg Prokofiev commented that "he tried to help so many people that ... less and less attention was paid to his pleas." Shostakovich was an agnostic and stated when asked if he believed in God, "No, and I am very sorry about it."

Shostakovich's response to official criticism and, what is more important, the question of whether he used music as a kind of covert dissidence is a matter of dispute. He outwardly conformed to government policies and positions, reading speeches and putting his name to articles expressing the government line. But it is evident he disliked many aspects of the regime, as confirmed by his family, his letters to Isaak Glikman, and the satirical cantata "Rayok", which ridiculed the "anti - formalist" campaign and was kept hidden until after his death. He was a close friend of Marshal of the Soviet Union Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who was executed in 1937 during the Great Purge.

It is also uncertain to what extent Shostakovich expressed his opposition to the state in his music. The revisionist view was put forth by Solomon Volkov in the 1979 book Testimony, which was claimed to be Shostakovich's memoirs dictated to Volkov. The book alleged that many of the composer's works contained coded anti - government messages, that would place Shostakovich in a tradition of Russian artists outwitting censorship that goes back at least to the early 19th century poet Pushkin. It is known that he incorporated many quotations and motifs in his work, most notably his signature DSCH theme. His longtime collaborator Evgeny Mravinsky said that "Shostakovich very often explained his intentions with very specific images and connotations."

The revisionist perspective has subsequently been supported by his children, Maxim and Galina, and many Russian musicians. Volkov has further argued, both in Testimony and in Shostakovich and Stalin, that Shostakovich adopted the role of the yurodivy or holy fool in his relations with the government. Other prominent revisionists are Ian MacDonald, whose book The New Shostakovich put forward further revisionist interpretations of his music, and Elizabeth Wilson, whose Shostakovich: A Life Remembered provides testimony from many of the composer's acquaintances.

Musicians and scholars including Laurel Fay and Richard Taruskin contest the authenticity and debate the significance of Testimony, alleging that Volkov compiled it from a combination of recycled articles, gossip, and possibly some information direct from the composer. Fay documents these allegations in her 2002 article 'Volkov's Testimony reconsidered', showing that the only pages of the original Testimony manuscript that Shostakovich had signed and verified are word - for - word reproductions of earlier interviews given by the composer, none of which are controversial. (Against this, it has been pointed out by Allan B. Ho and Dmitry Feofanov that at least two of the signed pages contain controversial material: for instance, "on the first page of chapter 3, where [Shostakovich] notes that the plaque that reads 'In this house lived [Vsevolod] Meyerhold' should also say 'And in this house his wife was brutally murdered'.") More broadly, Fay and Taruskin argue that the significance of Shostakovich is in his music rather than his life, and that to seek political messages in the music detracts from, rather than enhances, its artistic value.

In May 1958, during a visit to Paris, Shostakovich recorded his two piano concertos with André Cluytens, as well as some short piano works. These were issued by EMI on an LP, reissued by Seraphim Records on LP, and eventually digitally remastered and released on CD. Shostakovich recorded the two concertos in stereo in Moscow for Melodiya. Shostakovich also played the piano solos in recordings of the Cello Sonata, Op. 40 with cellist Daniil Shafran and also with Mstislav Rostropovich; the Violin Sonata, Op. 134, with violinist David Oistrakh; and the Piano Trio, Op. 67 with violinist David Oistrakh and cellist Miloš Sádlo.

There is also a short sound film of Shostakovich as soloist in a 1930s

concert performance of the closing moments of his first piano concerto. A

color film of Shostakovich supervising one of his operas, from his

last year, was also made.

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (Russian: Игорь Фёдорович Стравинский; 17 June [O.S. 5 June] 1882 – 6 April 1971) was a Russian, and later French and American, composer, pianist and conductor.

He is acknowledged by some as one of the most important and influential composers of 20th century music. He was named by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people of the century. He became a naturalized French citizen in 1934 and a naturalized US citizen in 1945. In addition to the recognition he received for his compositions, he achieved fame as a pianist and a conductor, often at the premieres of his works.

Stravinsky's compositional career was notable for its stylistic diversity. He first achieved international fame with three ballets commissioned by the impresario Sergei Diaghilev and performed by Diaghilev's Ballets Russes (Russian Ballets): The Firebird (1910), Petrushka (1911 / 1947), and The Rite of Spring (1913). The Rite, whose premiere provoked a riot, transformed the way in which subsequent composers thought about rhythmic structure, and was largely responsible for Stravinsky's enduring reputation as a musical revolutionary, pushing the boundaries of musical design.

After this first Russian phase, Stravinsky turned to neoclassicism in the 1920s. The works from this period tended to make use of traditional musical forms (concerto grosso, fugue, symphony), frequently concealed a vein of intense emotion beneath a surface appearance of detachment or austerity, and often paid tribute to the music of earlier masters, for example J.S. Bach and Tchaikovsky.

In the 1950s he adopted serial procedures, using the new techniques over his last twenty years. Stravinsky's compositions of this period share traits with examples of his earlier output: rhythmic energy, the construction of extended melodic ideas out of a few two- or three - note cells, and clarity of form, of instrumentation, and of utterance.

He

published a number of books throughout his career, almost always with

the aid of a collaborator, sometimes uncredited. In his 1936

autobiography, Chronicles of My Life, written with the help of Walter Nouvel,

Stravinsky included his well known statement that "music is, by its

very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all." With Alexis Roland - Manuel and Pierre Souvtchinsky he wrote his 1939 – 40 Harvard University Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, which were delivered in French and later collected under the title Poétique musicale in 1942 (translated in 1947 as Poetics of Music). Several interviews in which the composer spoke to Robert Craft were published as Conversations with Igor Stravinsky. They collaborated on five further volumes over the following decade.

Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum (renamed Lomonosov in 1948), Russia and brought up in Saint Petersburg. His childhood, he recalled in his autobiography, was troubled: "I never came across anyone who had any real affection for me." His parents were Anna Kholodovsky and Fyodor Stravinsky, a bass singer at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, and the young Stravinsky began piano lessons and later studied music theory and attempted some composition. In 1890, Stravinsky saw a performance of Tchaikovsky's ballet The Sleeping Beauty at the Mariinsky Theater; the performance, his first exposure to an orchestra, mesmerized him. At fourteen, he had mastered Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto in G minor, and the next year, he finished a piano reduction of one of Glazunov's string quartets.

Despite his enthusiasm for music, his parents expected him to become a lawyer. Stravinsky enrolled to study law at the University of Saint Petersburg in 1901, but was ill suited for it, attending fewer than 50 class sessions in four years. By the death of his father in 1902, he had already begun spending more time on his musical studies. Because of the closure of the university in the spring of 1905, in the aftermath of Bloody Sunday, Stravinsky was prevented from taking his law finals, and received only a half course diploma, in April 1906. Thereafter, he concentrated on music. On the advice of Nikolai Rimsky - Korsakov, probably the leading Russian composer of the time, he decided not to enter the Saint Petersburg Conservatoire, in large part because of his age; instead, in 1905, he began to take twice weekly private lessons from Rimsky - Korsakov, who became like a second father to him. These lessons continued until 1908.

In 1905 he was betrothed to his cousin Katerina Nossenko, whom he had known since early childhood. In spite of the Orthodox Church's opposition to marriage between first cousins, they managed to marry on 23 January 1906. Their first two children, Fyodor and Ludmilla, were born in 1907 and 1908 respectively.

In 1909, his Feu d'artifice (Fireworks), was performed in Saint Petersburg, where it was heard by Sergei Diaghilev, the director of the Ballets Russes in

Paris. Diaghilev was sufficiently impressed to commission Stravinsky to

carry out some orchestrations, and then to compose a full length ballet

score, The Firebird.

Stravinsky travelled to Paris in 1910 to attend the premiere of The Firebird. His family soon joined him, and decided to remain in the West for a time. He moved to Switzerland, where he lived until 1920 in Clarens and Lausanne. During this time he composed three further works for the Ballets Russes — Petrushka (1911), written in Lausanne, and The Rite of Spring (1913) and Pulcinella, both written in Clarens.

While the Stravinskys were in Switzerland, their second son, Soulima (who later became a minor composer), was born in 1910; and their second daughter, Maria Milena, was born in 1913. During this last pregnancy, Katerina was found to have tuberculosis, and she was placed in a Swiss sanatorium located in Leysin for her confinement. After a brief return to Russia in July 1914 to collect research materials for Les noces, Stravinsky left his homeland and returned to Switzerland just before the outbreak of World War I brought about the closure of the borders. He was not to return to Russia for nearly fifty years. Stravinsky was one of the few Eastern Orthodox or Russian Orthodox community representatives living in Switzerland at that time and is still remembered as such in Switzerland to date.

The

Stravinskys had significant financial difficulties at this period. The

fact that Russia (and, subsequently, the USSR) did not adhere to the

Berne convention created problems for him in collecting royalties for

performances of his works. Stravinsky himself also blamed Diaghilev for,

in his view, failing at this time to live up to the terms of a contract

they had signed. Stravinsky approached the Swiss philanthropist Werner Reinhart for financial assistance when he was writing Histoire du soldat (The Soldier's Tale). The first performance was conducted by Ernest Ansermet on 28 September 1918, at the Theatre Municipal de Lausanne.

Werner Reinhart sponsored and to a large degree underwrote this

performance. In gratitude, Stravinsky dedicated the work to Reinhart, and even gave him the original manuscript. Reinhart continued his support of Stravinsky's work in 1919 by funding a series of concerts of his recent chamber music. These included a suite of five numbers from The Soldier's Tale, arranged for clarinet, violin, and piano, which was a nod to Reinhart, who was an excellent amateur clarinettist. The

suite was first performed on 8 November 1919, in Lausanne, long before

the better known suite for the seven original performers became widely

known. In gratitude for Reinhart's ongoing support, Stravinsky dedicated his Three Pieces for Clarinet (composed October – November 1918) to Reinhart.

Stravinsky moved to France in 1920, where he formed a business and musical relationship with the French piano manufacturer Pleyel. Pleyel essentially acted as his agent in collecting mechanical royalties for his works, and in return provided him with a monthly income and a studio space in which to work and to entertain friends and business acquaintances.

Stravinsky arranged (and to some extent re-composed) many of his early works for the Pleyela, Pleyel's brand of player piano. Stravinsky did so in a way that made full use of the piano's 88 notes, without regard for the number or span of human fingers and hands. These were not recorded rolls, but were instead marked up from a combination of manuscript fragments and handwritten notes by the French musician, Jacques Larmanjat (musical director of Pleyel's roll department). While many of these works are now part of the standard repertoire, at the time many orchestras found his music beyond their capabilities and unfathomable. Major compositions issued on Pleyela piano rolls include The Rite of Spring, Petrushka, Firebird, Les noces and Song of the Nightingale. During the 1920s he recorded Duo - Art rolls for the Aeolian Company in both London and New York, not all of which survive.

After a short stay near Paris, Stravinsky moved with his family to the south of France. He returned to Paris in 1934, to live at the rue du Faubourg Saint - Honoré. Stravinsky later remembered this as his last and unhappiest European address; his wife's tuberculosis infected his eldest daughter Ludmila, and Stravinsky himself. Ludmila died in 1938, Katerina in the following year. Stravinsky spent five months in hospital, during which time his mother also died.

Although his marriage to Katerina endured for 33 years, Vera de Bosset (1888 – 1982), the true love of his life and later his partner until his death, became his second wife. When Stravinsky met Vera in Paris in February 1921, she was married to the painter and stage designer Serge Sudeikin; however, they soon began an affair which led to her leaving her husband. From then until Katerina's death in 1939, Stravinsky led a double life, spending some of his time with his first family and the rest with Vera. Katerina soon learned of the relationship and accepted it as inevitable and permanent. He became a French citizen in 1934.

During

his later years in Paris, Stravinsky had developed professional

relationships with key people in the United States; he was already

working on the Symphony in C for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra,

and had agreed to lecture at Harvard during the academic year of

1939 – 40. When World War II broke out in September 1939, Stravinsky moved

to the United States. Vera followed him early in the next year and they

were married in Bedford, Massachusetts, on 9 March 1940.

Stravinsky settled down in the Los Angeles area (1260 North Wetherly Drive, West Hollywood) where, in the end, he spent more time as a resident than any other city during his lifetime. He became a naturalized US citizen in 1945. Stravinsky had adapted to life in France, but moving to America at the age of 58 was a very different prospect. For a time, he preserved a ring of emigré Russian friends and contacts, but eventually found that this did not sustain his intellectual and professional life. He was drawn to the growing cultural life of Los Angeles, especially during World War II, when so many writers, musicians, composers, and conductors settled in the area; these included Otto Klemperer, Thomas Mann, Franz Werfel, George Balanchine and Arthur Rubinstein. He lived fairly near to Arnold Schoenberg, though he did not have a close relationship with him. Bernard Holland notes that he was especially fond of British writers who often visited him in Beverly Hills, "like W.H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, Dylan Thomas (who shared the composer's taste for hard spirits) and, especially, Aldous Huxley, with whom Stravinsky spoke in French." He settled into life in Los Angeles and sometimes conducted concerts with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, at the famous Hollywood Bowl, and other orchestras throughout the U.S. His plans to write an opera with W. H. Auden coincided with his meeting the conductor and musicologist Robert Craft. Craft lived with Stravinsky until the composer's death, acting as interpreter, chronicler, assistant conductor, and factotum for countless musical and social tasks.

Stravinsky's unconventional major seventh chord in his arrangement of "The Star - Spangled Banner" led to an incident with the Boston police on 15 January 1944, but he was only warned that Massachusetts could impose a $100 fine upon any "rearrangement of the national anthem in whole or in part." The incident soon established itself as a myth in which Stravinsky was supposedly arrested for playing the music.

Stravinsky was on the lot of Paramount Pictures when the musical score to the 1956 film The Court Jester (starring Danny Kaye) was being recorded. The red "recording in progress" light was illuminated to ensure no interruptions, Vic Schoen, the composer of the score, started to conduct a cue but noticed that the entire orchestra had turned to look at Stravinsky, who had just walked into the studio.Schoen said, "The entire room was astonished to see this short little man with a big chest walk in and listen to our session. I later talked with him after we were done recording. We went and got a cup of coffee together. After listening to my music Stravinsky had told me 'You have broken all the rules'. At the time I didn't understand his comment because I had been self taught. It took me years to figure out what he had meant."

In 1959, Stravinsky was awarded the Sonning Award, Denmark's highest musical honour. In 1962, he accepted an invitation to return to Leningrad (today known as Saint Petersburg) for a series of concerts. He also visited Moscow. Stravinsky met several leading Soviet composers, including Dmitri Shostakovich and Aram Khachaturian.

In 1969, he moved to New York where he lived his last years at the Essex House. Two years later, he died at the age of 88 in New York City and was buried in Venice on the cemetery island of San Michele. His grave is close to the tomb of his long - time collaborator Sergei Diaghilev.

Stravinsky's professional life had encompassed most of the 20th

century, including many of its modern classical music styles, and he

influenced composers both during and after his lifetime. He has a star

on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6340 Hollywood Boulevard and posthumously received the Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1987. Stravinsky was inducted into the National Museum of Dance C.V. Whitney Hall of Fame in 2004.

Stravinsky displayed an inexhaustible desire to explore and learn about art, literature, and life. This desire manifested itself in several of his Paris collaborations. Not only was he the principal composer for Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, but he also collaborated with Pablo Picasso (Pulcinella, 1920), Jean Cocteau (Oedipus Rex, 1927) and George Balanchine (Apollon musagète, 1928). His taste in literature was wide, and reflected his constant desire for new discoveries. The texts and literary sources for his work began with a period of interest in Russian folklore, progressed to classical authors and the Latin liturgy, and moved on to contemporary France (André Gide, in Persephone) and eventually English literature, including Auden, T.S. Eliot and medieval English verse.

According to Craft, Stravinsky remained a confirmed Monarchist throughout his life and loathed the Bolsheviks from the very beginning. In 1930, he remarked "I don't believe that anyone venerates Mussolini more

than I... I know many exalted personages, and my artist's mind does not

shrink from political and social issues. Well, after having seen so

many events and so many more or less representative men, I have an

overpowering urge to render homage to your Duce. He is the saviour of

Italy and – let us hope – Europe." Later, after a private audience with

Mussolini, he added: "Unless my ears deceive me, the voice of Rome is

the voice of Il Duce. I told him that I felt like a fascist myself....

In spite of being extremely busy, Mussolini did me the great honour of

conversing with me for three - quarters of an hour. We talked about music,

art and politics." When the Nazis placed Stravinsky's works on the list of "Entartete Musik",

he lodged a formal appeal to establish his Russian genealogy and

declared "I loathe all communism, Marxism, the execrable Soviet monster,

and also all liberalism, democratism, atheism, etc." Towards the end of his life, at Craft's behest, he made a return visit to his

native country in the 1960s, and composed a cantata in Hebrew and traveled to Israel for its performance.

Patronage was never far away. In the early 1920s, Leopold Stokowski gave Stravinsky regular support through a pseudonymous "benefactor". The composer was also able to attract commissions: most of his work from The Firebird onwards was written for specific occasions and was paid for generously.

Stravinsky proved adept at playing the part of "man of the world", acquiring a keen instinct for business matters and appearing relaxed and comfortable in many of the world's major cities. Paris, Venice, Berlin, London, Amsterdam and New York City all hosted successful appearances as pianist and conductor. Most people who knew him through dealings connected with performances spoke of him as polite, courteous and helpful.

Stravinsky was reputed to have been a philanderer, rumored to have had affairs with high profile partners such as Coco Chanel. Stravinsky never referred to such an affair himself, but Chanel spoke about it at length to her biographer Paul Morand in 1946, and the conversation was published 30 years later. The accuracy of Chanel's claims have been disputed by Stravinsky's widow Vera and his amanuensis Robert Craft, beginning two years after the publication of Morand's biography, even while conceding the existence of the affair itself. The Chanel fashion house states that the affair between Coco and Igor should be viewed as fiction as there was no proof. A fictionalization of such an affair forms the basis of the 2002 novel Coco and Igor, later made into a movie in 2009. Despite these supposed liaisons, Stravinsky was a family man who devoted considerable amounts of his time and money to his sons and daughters.

Stravinsky was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church during

most of his life, remarking at one time, "Music praises God. Music is

well or better able to praise him than the building of the church and

all its decoration; it is the Church's greatest ornament." Although

Stravinsky was not outspoken about his faith, he was a deeply religious

man throughout some periods of his life. As a child, he was brought up

by his parents in the Russian Orthodox Church. Baptized at birth, he later rebeled against the Church and abandoned it by the time he was fourteen or fifteen. Throughout

the rise of his career, he was estranged from Christianity and was not

until his early forties that he experienced a spiritual crisis. After

befriending a Russian priest, Father Nicolas, after his move to Nice in 1924, he reconnected with his faith and rejoined the Russian Orthodox Church. For the majority of his remaining life, he remained a committed Christian. Robert Craft noted that Stravinsky prayed daily, prayed before and after composing, and prayed when facing difficulty. Towards the end of his life, Stravinsky no longer attended services although he remained Russian Orthodox.

In Stravinsky's own words in his late seventies:

Stravinsky's career may be divided roughly into three stylistic periods.I cannot now evaluate the events that, at the end of those thirty years, made me discover the necessity of religious belief. I was not reasoned into my disposition. Though I admire the structured thought of theology (Anselm's proof in the Fides Quaerens Intellectum, for instance) it is to religion no more than counterpoint exercises are to music. I do not believe in bridges of reason or, indeed, in any form of extrapolation in religious matters. ... I can say, however, that for some years before my actual "conversion," a mood of acceptance had been cultivated in me by a reading of the Gospels and by other religious literature. ...

The first period (excluding some early minor works) began with Feu d'artifice (Fireworks) and achieved prominence with the three ballets composed for Diaghilev. These three works have several characteristics in common: they are scored for an extremely large orchestra; they use Russian folk themes and motifs; and they are influenced by Rimsky - Korsakov's imaginative scoring and instrumentation. They also exhibit considerable stylistic development: from The Firebird, which emphasizes certain tendencies in Rimsky - Korsakov and features pandiatonicism conspicuously in the third movement, to the use of polytonality in Petrushka, and the intentionally brutal polyrhythms and dissonances of The Rite of Spring.

The first of the ballets, The Firebird, is noted for its imaginative orchestration, evident at the outset from the introduction in 12/8 meter, which exploits the low register of the double bass. Petrushka, the first of Stravinsky's ballets to draw on folk mythology, is also distinctively scored. In the third ballet, The Rite of Spring, the composer attempted to depict musically the brutality of pagan Russia, which inspired the violent motifs that recur throughout the work.

If Stravinsky's stated intention was "to send them all to hell", then he may have rated the 1913 premiere of The Rite of Spring as a success: it is among the most famous classical music riots, and Stravinsky referred to it frequently as a "scandale" in his autobiography. There were reports of fistfights among the audience, and the need for a police presence during the second act. The real extent of the tumult, however, is open to debate, and these reports may be apocryphal.

Other pieces from this period include: Le Rossignol (The Nightingale); Renard (1916); Histoire du soldat (The Soldier's Tale) (1918); and Les noces (The Wedding) (1923).

The next phase of Stravinsky's compositional style extended from Mavra (1921 – 22), regarded as the start of Stravinsky's neo - classicism, until 1952, when he turned to serialism. Pulcinella (1920) and the Octet (for wind instruments, 1923) are Stravinsky's first compositions to feature his re-examination of the classical music of Mozart and Bach and their contemporaries.

Other works such as Oedipus Rex (1927), Apollon musagète (1928, for the Russian Ballet) and the Dumbarton Oaks Concerto (1937 – 38) continued this re-thinking of eighteenth century musical styles.

Works from this period include the three symphonies: the Symphonie des Psaumes (Symphony of Psalms, 1930), Symphony in C (1940) and Symphony in Three Movements (1945). Apollon, Persephone (1933) and Orpheus (1947) exemplify not only Stravinsky's return to music of the Classical period, but also his exploration of themes from the ancient Classical world such as Greek mythology.

Stravinsky completed his last neo - classical work, the opera The Rake's Progress, in 1951, to a libretto by W.H. Auden based on the etchings of Hogarth.

It was premiered in Venice in 1951, and given further production in

Vienna, Geneva, Strasbourg, and several locations in Germany the next year, before being staged in Paris and New York (at the Metropolitan Opera) in 1953. It was staged by the Santa Fe Opera in a 1962 Stravinsky Festival in honor of the composer's 80th birthday. The

music is direct but quirky; it borrows from classic tonal harmony but

also interjects surprising dissonances; it features Stravinsky's

trademark off rhythms; and it harks back to the operas and themes of Monteverdi, Gluck and Mozart. The opera was revived by the Metropolitan Opera in 1997.

Stravinsky began using serial compositional techniques, including dodecaphony, the twelve - tone technique originally devised by Arnold Schoenberg, in the early 1950s (after Schoenberg's death).

He first experimented with non - twelve - tone serial technique in small scale vocal and chamber works such as the Cantata (1952), Septet (1953) and Three Songs from Shakespeare (1953), and his first composition to be fully based on these twelve - tone serial techniques is In Memoriam Dylan Thomas (1954). Agon (1954 – 57) is his first work to include a twelve - tone series, and Canticum Sacrum (1955) is his first piece to contain a movement entirely based on a tone row ("Surge, aquilo"). Stravinsky later expanded his use of dodecaphony in works including Threni (1958), A Sermon, a Narrative, and a Prayer (1961), and The Flood (1962), which are based on biblical texts.

Agon, written from 1954 to 1957, is a ballet choreographed for twelve dancers. It is an important transitional composition between Stravinsky's neo - classical period and his serial style. Some numbers of Agon are reminiscent of the "white - note" tonality of his neo - classic period, while others (for example Bransle Gay) display his re-interpretation of serial methods.

Stravinsky is known as "one of music's truly epochal innovators". The

most important aspect of Stravinsky's work aside from his technical

innovations, including in rhythm and harmony, is the "changing face" of

his compositional style while always "retaining a distinctive, essential

identity". He

himself was inspired by different cultures, languages and literatures.

As a consequence, his influence on composers both during his lifetime and after his death was, and remains, considerable.

Stravinsky's use of motivic development (the use of musical figures that are repeated in different guises throughout a composition or section of a composition) included additive motivic development. This is where notes are subtracted or added to a motif without regard to the consequent changes in meter. A similar technique may be found as early as the sixteenth century, for example in the music of Cipriano de Rore, Orlandus Lassus, Carlo Gesualdo, and Giovanni de Macque, music with which Stravinsky exhibited considerable familiarity.

The Rite of Spring is notable for its relentless use of ostinati; for example, in the eighth note ostinato on strings accented by eight horns in the section Augurs of Spring (Dances of the Young Girls). The work also contains passages where several ostinati clash against one another.

Stravinsky was noted for his distinctive use of rhythm, especially in The Rite of Spring. According to Philip Glass:

the idea of pushing the rhythms across the bar lines [...] led the way [...]. The rhythmic structure of music became much more fluid and in a certain way spontaneous

Elsewhere, Glass mentions Stravinsky's "primitive, offbeat rhythmic drive". According to Andrew J. Browne, "Stravinsky is perhaps the only composer who has raised rhythm in itself to the dignity of art." Stravinsky's rhythm and vitality greatly influenced composer Aaron Copland.

Stravinsky's first neo - classical works were the ballet Pulcinella of 1920, and the stripped down and delicately scored Octet for Wind Instruments of 1923. Stravinsky may have been preceded in his use of neoclassical devices by composers such as Sergei Prokofiev and Erik Satie. By the late 1920s and 1930s, the use by composers of neoclassicism had become widespread.

Stravinsky continued a long tradition, stretching back at least to the fifteenth century in the form of the quodlibet and parody mass, by composing pieces which elaborate on individual works by earlier composers. An early example of this is his Pulcinella of 1920, in which he used music which at the time was attributed to Giovanni Pergolesi as source material, at times quoting it directly and at other times reinventing it. He developed the technique further in the ballet The Fairy's Kiss of 1928, based on the music — mostly piano pieces — ofT chaikovsky. Later examples of comparable musical transformations include Stravinsky's use of Schubert's Marche Militaire No. 1 in Circus Polka (1942) and "Happy Birthday to You" in Greeting Prelude (1955).

In The Rite of Spring Stravinsky

stripped folk themes to their most basic melodic outlines, and often

contorted them beyond recognition with added notes, and other techniques

including inversion and diminution.

Like many of the late romantic composers, Stravinsky often called for huge orchestral forces, especially in the early ballets. His first breakthrough The Firebird proved him the equal of Nikolai Rimsky - Korsakov and lit the "fuse under the instrumental make-up of the 19th century orchestra". In The Firebird he took the orchestra apart and analyzed it. The Rite of Spring on the other hand has been characterized by Aaron Copland as the foremost orchestral achievement of the 20th century.

Stravinsky also wrote for unique combinations of instruments in smaller ensembles, chosen for their precise tone colours. For example, Histoire du soldat (The Soldier's Tale) is scored for clarinet, bassoon, cornet, trombone, violin, double bass and percussion, a strikingly unusual combination for 1918.

Stravinsky occasionally exploited the extreme ranges of instruments, most famously at the opening of The Rite of Spring where Stravinsky uses the extreme upper reaches of the bassoon to simulate the symbolic "awakening" of a spring morning.

Erik Satie wrote an article about Igor Stravinsky that was published in Vanity Fair. Satie had met Stravinsky for the first time in 1910. Satie's attitude towards the Russian composer is marked by deference, as can be seen from the letters he wrote him in 1922, preparing for the Vanity Fair article. With a touch of irony, he concluded one of these letters "I admire you: are you not the Great Stravinsky? I am but little Erik Satie." In the published article, Satie argued that measuring the "greatness" of an artist by comparing him to other artists, as if speaking about some "truth", is illusory: every piece of music should be judged on its own merits, not by comparing it to the standards of other composers. That was exactly what Jean Cocteau had done, when commenting deprecatingly on Stravinsky in his 1918 book Le Coq et l'Arlequin.

According to The Musical Times in 1923:

All the signs indicate a strong reaction against the nightmare of noise and eccentricity that was one of the legacies of the war.... What has become of the works that made up the program of the Stravinsky concert which created such a stir a few years ago? Practically the whole lot are already on the shelf, and they will remain there until a few jaded neurotics once more feel a desire to eat ashes and fill their belly with the east wind.

In 1935, American composer Marc Blitzstein compared Stravinsky to Jacopo Peri and C.P.E. Bach, conceding that "There is no denying the greatness of Stravinsky. It is just that he is not great enough". Blitzstein's Marxist position is that Stravinsky's wish was to "divorce music from other streams of life," which is "symptomatic of an escape from reality", resulting in a "loss of stamina his new works show", naming specifically Apollo, the Capriccio, and Le Baiser de la fée.

Composer Constant Lambert described pieces such as Histoire du soldat (The Soldier's Tale) as containing "essentially cold - blooded abstraction". Lambert continued, "melodic fragments in Histoire du Soldat are completely meaningless themselves. They are merely successions of notes that can conveniently be divided into groups of three, five, and seven and set against other mathematical groups", and he described the cadenza for solo drums as "musical purity... achieved by a species of musical castration". He compared Stravinsky's choice of "the drabbest and least significant phrases" to Gertrude Stein's: "Everyday they were gay there, they were regularly gay there everyday" ("Helen Furr and Georgine Skeene", 1922), "whose effect would be equally appreciated by someone with no knowledge of English whatsoever".

In his book Philosophy of Modern Music (1949), Theodor W. Adorno called Stravinsky an acrobat and spoke of hebephrenic and psychotic traits in several of Stravinsky's works. Contrary to a common misconception, however, Adorno did not think that the hebephrenic and psychotic imitations Stravinsky's music was supposed to contain were its main fault, as he clearly pointed out in a postscriptum added later to his "Philosophy": Adorno's criticism of Stravinsky is more concerned with the "transition to 'positivity'" Adorno found in Stravinsky's neoclassical works. Part of the composer's error, in Adorno's view, was his neo - classicism, but more important was his music's "pseudomorphism of painting," playing off le temps espace (time - space) rather than le temps durée (time - duration) of Henri Bergson. "One trick characterizes all of Stravinsky's formal endeavors: the effort of his music to portray time as in a circus tableau and to present time complexes as though they were spatial. This trick, however, soon exhausts itself." His "rhythmic procedures closely resemble the schema of catatonic conditions. In certain schizophrenics, the process by which the motor apparatus becomes independent leads to infinite repetition of gestures or words, following the decay of the ego."

Stravinsky's reception in Russia and the USSR went back and forth. Performances of his music stopped from around 1933 until 1962, when Nikita Khrushchev invited Stravinsky for an official state visit. In 1972 an official proclamation by the Soviet Minister of Culture, Ekaterina Furtseva, ordered Soviet musicians to "study and admire" Stravinsky's music, and made hostility toward it a potential offense.

According to Gabriel Josipovici, The Rake's Progress is perhaps the only one of Stravinsy's works that "gives a justification in terms of human psychology, and of the realities of our world, for that obsessional need to repeat and return".

While Stravinsky's music has been criticized for its range of styles, scholars had "gradually begun to perceive unifying elements in Stravinsky's music" by the 1980s. Earlier writers, such as Aaron Copland, Elliott Carter, Boris de Schloezer, and Virgil Thomson, writing in Modern Music (a quarterly review published between 1925 and 1946), could find only a common "'seriousness' of 'tone' or of 'purpose', 'the exact correlation between the goal and the means', or a dry 'ant - like neatness'".

However, from the mid 1960s onward Stravinsky's influence is encountered in many musicians' work, including Steve Reich, Philip Glass and others.

He was honored in 1982 by the United States Postal Service with a 2¢ Great Americans series postage stamp.

Igor Stravinsky found recordings a practical and useful tool in preserving his own thoughts on the interpretation of his music. As a conductor of his own music, he recorded primarily for Columbia Records, beginning in 1928 with a performance of the original suite from The Firebird and concluding in 1967 with the 1945 suite from the same ballet. In the late 1940s, he made several recordings for RCA Victor at the Republic Studios in Los Angeles. Although most of his recordings were made with studio musicians, he also worked with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Cleveland Orchestra, the CBC Symphony Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, theRoyal Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Bavarian Broadcasting Symphony Orchestra.

During his lifetime, Stravinsky appeared on several telecasts, including the 1962 world premiere of The Flood on CBS television; although Stravinsky appeared on the telecast, the actual performance was conducted by Robert Craft. Numerous films and videos of the composer have been preserved.