<Back to Index>

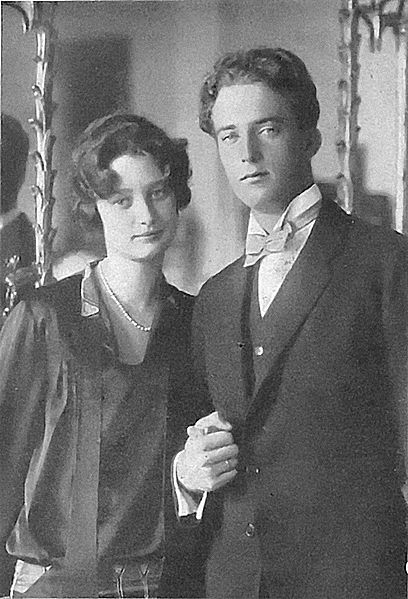

- Emperor of Austria Charles I, 1887

- King of the Belgians Leopold III, 1901

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles I of Austria or Charles IV of Hungary (German: Karl Franz Joseph Ludwig Hubert Georg Otto Marie von Habsburg - Lothringen, English: Charles Francis Joseph Louis Hubert George Otto Mary of Habsburg - Lorraine, Hungarian: IV. Károly or Habsburg - Lotaringiai Károly Ferenc József Lajos Hubert György Mária, Italian: Carlo Francesco Giuseppe Ludovico Giorgio Ottone Maria d'Asburgo Lorena, Polish: Karol Franciszek Józef Ludwik Hubert Jerzy Otto Maria Habsbursko - Lotaryński, Ukrainian:Карл І Франц Йосиф) (17 August 1887 – 1 April 1922) was (among other titles) the last ruler of the Austro - Hungarian Empire. He was the last Emperor of Austria, the last King of Hungary, the last King of Bohemia and Croatia and the last King of Galicia and Lodomeria and the last monarch of the House of Habsburg - Lorraine. He reigned as Charles I as Emperor of Austria and Charles IV as King of Hungary from 1916 until 1918, when he "renounced participation" in state affairs, but did not abdicate. He spent the remaining years of his life attempting to restore the monarchy until his death in 1922. Following his beatification by the Catholic Church, he has become commonly known as Blessed Charles of Austria.

Charles was born on 17 August 1887, in the Castle of Persenberg in Lower Austria. He was the son of Archduke Otto Franz of Austria (1865 – 1906) and Princess Maria Josepha of Saxony (1867 – 1944); he was also a nephew of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria - Este. As a child, Charles was reared a devout Catholic. In 1911, Charles married Princess Zita of Bourbon - Parma.

Charles became heir - presumptive with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, his uncle, in Sarajevo in 1914, the event which precipitated World War I. Charles succeeded to the thrones in November 1916, when his grand - uncle, Franz Josef I of Austria died. Charles also became a Generalfeldmarschall in the Austro - Hungarian Army.

On 2 December 1916, he took over the title of Supreme Commander of the whole army from Archduke Frederick. His coronation occurred on 30 December. In 1917, Charles secretly entered into peace negotiations with France. Although his foreign minister, Ottokar Czernin, was only interested in negotiating a general peace which would include Germany as well, Charles himself, in negotiations with the French with his brother - in - law, Prince Sixtus of Bourbon - Parma, an officer in the Belgian Army, as intermediary, went much further in suggesting his willingness to make a separate peace. When news of the overture leaked in April 1918, Charles denied involvement until the French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau published letters signed by him. This led to Czernin's resignation, forcing Austria - Hungary into an even more dependent position with respect to its seemingly wronged German ally.

The Austro - Hungarian Empire was wracked by inner turmoil in the final years of the war, with much tension between ethnic groups. As part of his Fourteen Points, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson demanded that the Empire allow for autonomy and self determination of its peoples. In response, Charles agreed to reconvene the Imperial Parliament and allow for the creation of a confederation with each national group exercising self governance. However, the ethnic groups fought for full autonomy as separate nations, as they were now determined to become independent from Vienna at the earliest possible moment.

Foreign Minister Baron Istvan Burián asked for an armistice based on the Fourteen Points on 14 October, and two days later Charles issued a proclamation that radically changed the nature of the Austrian state. The Poles were granted full independence with the purpose of joining their ethnic brethren in Russia and Germany in a Polish state. The rest of the Austrian lands were transformed into a federal union composed of four parts — German, Czech, South Slav and Ukrainian. Each of the four parts was to be governed by a federal council, and Trieste was to receive a special status. However, Secretary of State Robert Lansing replied four days later that the Allies were now committed to the causes of the Czechs, Slovaks and South Slavs. Therefore, autonomy for the nationalities was no longer enough. In fact, a Czechoslovak provisional government had joined the Allies on 14 October, and the South Slav national council declared an independent South Slav state on October 29, 1918.

The

Lansing note effectively ended any efforts to keep the Empire together.

One by one, the nationalities proclaimed their independence; even

before the note the national councils had been acting more like

provisional governments. Charles' political future became uncertain. On

31 October, Hungary officially ended the personal union between

Austria and Hungary. Nothing remained of Charles' realm except the

Danubian and Alpine provinces, and he was challenged even there by the German Austrian State Council. His last prime minister, Heinrich Lammasch, advised him that it was fruitless to stay on.

On 11 November 1918 — the same day as the armistice ending the war between allies and Germany — Charles issued a carefully worded proclamation in which he recognized the Austrian people's right to determine the form of the state and "relinquish(ed) every participation in the administration of the State." He also released his officials from their oath of loyalty to him. On the same day the Imperial Family left Schönbrunn and moved to Castle Eckartsau, east of Vienna. On 13 November, following a visit of Hungarian magnates, Charles issued a similar proclamation for Hungary.

Although it has widely been cited as an "abdication", that word was never mentioned in either proclamation. Indeed, he deliberately avoided using the word abdication in the hope that the people of either Austria or Hungary would vote to recall him.

Privately, Charles left no doubt that he believed himself to be the rightful emperor. Addressing Cardinal Friedrich Gustav Piffl, he wrote:

I did not abdicate, and never will. (...) I see my manifesto of 11 November as the equivalent to a cheque which a street thug has forced me to issue at gunpoint. (...) I do not feel bound by it in any way whatsoever.

Instead, on 12 November, the day after he issued his proclamation, the independent Republic of German Austria was proclaimed, followed by the proclamation of the Hungarian Democratic Republic on 16 November. An uneasy truce - like situation ensued and persisted until 23 March 1919, when Charles left for Switzerland, escorted by the commander of the small British guard detachment at Eckartsau, Lt. Col. Edward Lisle Strutt. As the Imperial Train left Austria on 24 March, Charles issued another proclamation in which he confirmed his claim of sovereignty, declaring that "whatever the national assembly of German Austria has resolved with respect to these matters since 11 November is null and void for me and my House."

Although the newly established republican government of Austria was not aware of this "Manifesto of Feldkirchen" at this time (it had been dispatched only to the Spanish King and to the Pope through diplomatic channels), the politicians now in power were extremely irritated by the Emperor's departure without an explicit abdication. On 3 April 1919, the Austrian Parliament passed the Habsburg Law, which permanently barred Charles and Zita from ever returning to Austria again. Other Habsburgs were banished from Austrian territory unless they renounced all intentions of reclaiming the throne and accepted the status of ordinary citizens. Another law, passed on the same day, abolished all nobility in Austria.

In Switzerland, Charles and his family briefly took residence at Castle Wartegg near Rorschach at Lake Constance, and moved to Château de Prangins at Lake Geneva on 20 May 1919.

Encouraged

by Hungarian royalists ("legitimists"), Charles sought twice in 1921 to

reclaim the throne of Hungary, but failed largely because Hungary's regent, Miklós Horthy (the

last admiral of the Austro - Hungarian Navy), refused to support him.

Horthy's failure to support Charles' restoration attempts is often

described as "treasonous" by royalists. Critics suggest that Horthy's

actions were more firmly grounded in political reality than those of

Charles and his supporters. Indeed, the neighboring countries had

threatened to invade Hungary if Charles tried to regain the throne.

Later in 1921, the Hungarian parliament formally nullified the Pragmatic Sanction, an act that effectively dethroned the Habsburgs.

After the second failed attempt at restoration in Hungary, Charles and pregnant Zita were briefly quarantined at Tihany Abbey. On 1 November 1921 they were taken to the Danube harbor city of Baja, made to board the British monitor HMS Glowworm, and were removed to the Black Sea where they were transferred to the light cruiser HMS Cardiff. They arrived in their final exile, the Portuguese island of Madeira, on 19 November 1921. Determined to prevent a third restoration attempt, the Council of Allied Powers had agreed on Madeira because it was isolated in the Atlantic and easily guarded.

Originally the couple and their children (who joined them only on 2 February 1922) lived at Funchal at the Villa Vittoria, next to Reid's Hotel, and later moved to Quinta do Monte. Compared to the imperial glory in Vienna and even at Eckartsau, conditions there were certainly impoverished, although not nearly comparable to the bleak conditions under which most of Charles' former subjects had to make a living after the war.

Charles

would not leave Madeira again. On 9 March 1922 he caught a cold walking

into town and developed bronchitis which subsequently progressed to severe pneumonia. Having suffered two heart attacks he died of respiratory failure on 1 April in the presence of his wife (who was pregnant with their eighth child) and 9 year old Crown Prince Otto, retaining consciousness almost to the last moment. His

remains except for his heart are still kept on the island, in the

Church of Our Lady of Monte, in spite of several attempts to move them

to the Habsburg Crypt in Vienna. His heart, and that of Empress Zita, repose in the Loreto Chapel of Muri Abbey.

Historians have been mixed in their evaluations of Charles and his reign. One of the most critical has been Helmut Rumpler, head of the Habsburg commission of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, who has described Charles as "a dilettante, far too weak for the challenges facing him, out of his depth, and not really a politician." However, others have seen Charles as a brave and honorable figure who tried as Emperor - King to halt World War I. The English writer, Herbert Vivian, wrote:

"Karl was a great leader, a Prince of peace, who wanted to save the world from a year of war; a statesman with ideas to save his people from the complicated problems of his Empire; a King who loved his people, a fearless man, a noble soul, distinguished, a saint from whose grave blessings come."

Furthermore, Anatole France, the French novelist, stated:

"Emperor Karl is the only decent man to come out of the war in a leadership position, yet he was a saint and no one listened to him. He sincerely wanted peace, and therefore was despised by the whole world. It was a wonderful chance that was lost."

Paul von Hindenburg, who at the time of Charles' reign was German army commander in chief, commented in his memoirs:

"He tried to compensate for the evaporation of the ethical power which emperor Franz Joseph had represented by offering ethnical reconciliation. Even as he dealt with elements who were sworn to the goal of destroying his empire he believed that his acts of political grace would have an impact on their conscience. These attempts were totally futile; those people had long ago lined up with our common enemies, and were far from being deterred."

Catholic Church leaders have praised Charles for putting his Christian faith first in making political decisions, and for his role as a peacemaker during the war, especially after 1917. They have considered that his brief rule expressed Roman Catholic social teaching, and that he created a social legal framework that in part still survives.

Pope John Paul II declared Charles "Blessed" in a beatification ceremony held on 3 October 2004, and stated:

The decisive task of Christians consists in seeking, recognizing and following God's will in all things. The Christian statesman, Charles of Austria, confronted this challenge every day. To his eyes, war appeared as "something appalling". Amid the tumult of the First World War, he strove to promote the peace initiative of my Predecessor, Benedict XV.

From the beginning, the Emperor Charles conceived of his office as a holy service to his people. His chief concern was to follow the Christian vocation to holiness also in his political actions. For this reason, his thoughts turned to social assistance.

The cause or campaign for his canonization began in 1949, when testimony of his holiness was collected in the Archdiocese of Vienna.

In 1954, the cause was opened and he was declared servant of God, the

first step in the process. The League of Prayers established for the

promotion of his cause has set up a website, and Cardinal Christoph Schönborn of Vienna has sponsored the cause.

- On 14 April 2003, the Vatican's Congregation for the Causes of Saints in the presence of Pope John Paul II, promulgated Charles of Austria's "heroic virtues, and he thereby acquired the title of venerable.

- On 21 December 2003, the Congregation certified, on the basis of three expert medical opinions, that a miracle in 1960 occurred through the intercession of Charles. The miracle attributed to Charles was the scientifically inexplicable healing of a Brazilian nun with debilitating varicose veins; she was able to get out of bed after she prayed for his beatification.

- On 3 October 2004, he was beatified by Pope John Paul II. The Pope also declared 21 October, the date of Charles' marriage in 1911 to Princess Zita, as Charles' feast day. The beatification has caused controversy because of the mistaken belief that Charles authorized the Austro - Hungarian Army's use of poison gas during World War I, when in fact he was the first, and only, world leader during the war who banned its use.

- On 31 January 2008, a Church tribunal, after a 16 month investigation, formally recognized a second miracle attributed to Charles I (required for his Canonization as a Saint in the Catholic Church); in an uncommon twist, the Florida woman claiming the miracle cure is not Catholic, but Baptist. However, due to her experiences, she became Catholic in the Latin Rite soon after.

- "Now, we must help each other to get to Heaven." Addressing Empress Zita on 22 October 1911, the day after their wedding.

- "I am an officer with all my body and soul, but I do not see how anyone who sees his dearest relations leaving for the front can love war." Addressing Empress Zita after the outbreak of World War I.

- "I have done my duty, as I came here to do. As crowned King, I not only have a right, I also have a duty. I must uphold the right, the dignity and honor of the Crown.... For me, this is not something light. With the last breath of my life I must take the path of duty. Whatever I regret, Our Lord and Savior has led me." Addressing Cardinal János Csernoch after the defeat of his attempt to regain the Hungarian throne in 1921. The British Government had vainly hoped that the Cardinal would be able to persuade him to renounce his title as King of Hungary.

- "I must suffer like this so my people will come together again." Spoken in Madeira, during his last illness.

- "I can't go on much longer... Thy will be done... Yes... Yes... As you will it... Jesus!" Reciting his last words while contemplating a crucifix held by Empress Zita.

Leopold III (born as Léopold Philippe Charles Albert Meinrad Hubertus Marie Miguel (French) or Leopold Filips Karel Albert Meinrad Hubertus Maria Miguel (Dutch) or Leopold Philipp Karl Albert Meinrad Hubertus Maria Miguel (German); 3 November 1901 – 25 September 1983) reigned as King of the Belgians from 1934 until 1951, when he abdicated in favor of the Heir Apparent, his son Baudouin.

Leopold III was born in Brussels as Prince Leopold of Belgium, Prince of Saxe - Coburg and Gotha, and succeeded to the throne of Belgium on 23 February 1934 following the death of his father, King Albert I.

He was invested as the 1,154th Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Spain in 1923, the 355th Grand Cross of the Order of the Tower and Sword in 1927 and the 833rd Knight of the Order of the Garter in 1935.

Crown Prince Leopold fought as a private during World War I with the 12th Belgian Regiment while still a teenager, but was sent by his father to Eton College in the United Kingdom, in 1915. After the war, in 1919, he enrolled at St. Anthony Seminary in Santa Barbara, California. He married Princess Astrid of Sweden in a civil ceremony in Stockholm on 4 November 1926, followed by a religious ceremony in Brussels on 10 November. The marriage produced three children:

- Joséphine - Charlotte, Princess of Belgium, born at the Royal Palace of Brussels on 11 October 1927, Grand Duchess of Luxembourg. She was married on 9 April 1953 to Prince Jean, later Grand - Duke of Luxembourg. She died at Fischbach Castle on 10 January 2005.

- Baudouin, Duke of Brabant, Count of Hainaut, Prince of Belgium, who became the fifth King of the Belgians as Baudouin, born at Stuyvenberg on the outskirts of Brussels on 7 September 1930, and died at Motril, Spain, on 31 July 1993.

- Albert, Prince of Liège, Prince of Belgium, born at Stuyvenberg on 6 June 1934; King of the Belgians Albert II.

On 29 August 1935, while the King and Queen were driving along the winding, narrow roads near their villa at Küssnacht am Rigi, Schwyz, Switzerland, on the shores of Lake Lucerne, Leopold lost control of the car which plunged into the lake, killing Queen Astrid and her unborn fourth child.

Leopold married Lilian Baels on 11 September 1941 in a secret, religious ceremony, with no validity under Belgian law. They originally intended to wait until the end of the war for the civil marriage, but as the new Princesse de Réthy was soon expecting their first child, the ceremony took place on 6 December 1941. They had three children in total:

- Alexander, Prince of Belgium, born in Brussels on 18 July 1942. In 1991, he married Lea Inga Dora Wohlman, a marriage revealed only seven years later. She was created a Princess of Belgium in her own right. He died on November 29, 2009.

- Marie - Christine, Princess of Belgium, born in Brussels on 6 February 1951. Her first marriage, to Paul Drucker in 1981, lasted 40 days (though they were not formally divorced until 1985); she subsequently married Jean - Paul Gourges in 1989.

- Maria - Esmeralda, Princess of Belgium, born in Brussels on 30 September 1956, a journalist, her professional name is Esmeralda de Réthy. She married Salvador Moncada, a noted pharmacologist, in 1998. They have a son and a daughter.

When World War II broke out in September 1939, the French and British governments immediately sought to persuade Belgium to join them. Leopold and his government refused, maintaining Belgium's neutrality. Belgium considered itself well prepared against a possible invasion by Axis forces, for during the 1930s Leopold had made extensive preparations against an invasion of his country, historically a battlefield in wars between French and Germans.

On 10 May 1940 the German army invaded Belgium. On the first day of the offensive the Belgian fortifications were penetrated before any French or British troops could arrive and the country was overwhelmed by the numerically superior Germans.

Nevertheless,

the Belgian perseverance prevented the British Expeditionary Force from

being outflanked and cut off from the coast, enabling the evacuation from Dunkirk.

After his military surrender Leopold stayed on in Brussels to face the

victorious invaders, while his entire civil government fled to Paris and

later to London.

On 24 May 1940, Leopold, having assumed command of the Belgian army, met with his ministers for what would be the final time. The ministers urged the king to leave the country with the Government. Prime Minister Hubert Pierlot reminded Leopold that capitulation was a decision for the Belgian government, not the king. The king indicated that he had decided to remain in Belgium with his troops, whatever the outcome. The ministers took this to mean that he would establish a new government under the direction of Hitler, potentially a treasonous act. Leopold thought that he might be seen as a deserter when he left the country: "Whatever happens, I have to share the same fate as my troops." Leopold had long had a difficult and contentious relationship with his ministers, acting independently of government influence whenever possible, and seeking to circumvent and even limit the ministers' powers, while expanding his own.

Along with the Belgian troops, French and British troops were encircled by German forces at Dunkirk. The King notified King George VI by telegram on 25 May 1940 that Belgian forces were being crushed, saying "assistance which we give to the Allies will come to an end if our Army is surrounded". Two days later (27 May 1940), Leopold surrendered the Belgian forces to the Germans.

Prime Minister Pierlot spoke on French radio, saying that the king's decision to surrender went against the Belgian Constitution. The decision, he said, was not only a military decision but also a political decision, and the king had acted without his ministers' advice, and therefore contrary to the Constitution. Pierlot and his Government believed this created an impossibilité de régner:

| “ | Should the King find himself unable to reign, the ministers, having observed this inability, immediately summon the Chambers. Regency and guardianship are to be provided by the united Chambers. | ” |

But, at this time, in France (and further in the United Kingdom), it was impossible to summon the Chambers. It was also impossible to appoint a Regent. Accordingly, the Government would ask Leopold's brother Prince Charles to serve as Regent but only after the Liberation of Belgium in September 1944.

Leopold's action brought accusations of treason by French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud. Although French troops continued to fight the Germans, Flemish historians Valaers and Van Goethem wrote that Leopold III had become "The scapegoat of Reynaud" because the French Prime Minister was likely already aware that the Battle of France was lost.

Leopold's surrender was also decried by Winston Churchill: in the House of Commons on 4 June 1940 he said:

| “ | At the last moment when Belgium was already invaded, King Leopold called upon us to come to his aid, and even at the last moment we came. He and his brave, efficient Army, nearly half a million strong, guarded our left bank and thus kept open our only line of retreat to the sea. Suddenly, without prior consultation, with the least possible notice, without the advice of his ministers and upon his own personal act, he sent a plenipotentiary to the German Command, surrendered his Army and exposed our whole flank and means of retreat." | ” |

In 1949, Churchill's comments about the events of May 1940 were published in Le Soir (12 February 1949). Leopold's former secretary sent a letter to Churchill saying that Churchill was wrong. Churchill sent a copy of this letter to the King's brother, the Regent Prince Charles, via his secretary André de Staercke. In the letter Churchill wrote,

| “ | With regards to King Leopold, the words which I used at the time in the House of Commons are upon record and after careful consideration I do not see any reason to change them (...) it seemed to me and many others that the King should have been guided by the advice of his Ministers and should not have favoured a course which identified the capitulation of the Belgian Army with the submission of the Belgian State to Herr Hitler and consequently taking them out of the war. Happily this evil was averted, and in the end, all came right. I need scarcely say that nothing I said at the time could be interpreted as a reflection upon the personal courage or honour of King Leopold." | ” |

De Staercke replied that Churchill was right: "The Prince, Monsieur Spaak and I read your text which is saying the precise truth, which seems perfect to us."

André de Staercke was one of the most important witnesses to the Belgian government's internal crisis of 1940. At his request, his memoirs about Prince Charles (which he wrote at Churchill's suggestion) were only published after de Staercke's death in 2003, with the help of and a preface by Belgian historian Jean Stengers. The memoir underlines the fact that while King Baudouin of Belgium generally did not like the people who were opposed to his father at the time of the Royal question, de Staercke had become a friend of his. At the meal following the funeral of Prince Charles in June 1983, Baudouin placed de Staercke at his right.

Belgian historian Francis Balace wrote that capitulation was inevitable because the Belgian Army was not able to fight any longer against the German army. Even Churchill admitted that their position was perilous: in a telegram to Lord Gort on 27 May, only one day before the Belgian capitulation, he wrote, "We are asking them to sacrifice themselves for us."

Upon Leopold's surrender, the government ministers left for exile, mostly in France. When France fell at the end of June 1940, several ministers sought to return to Belgium. They made an overture to Leopold but were rebuffed:

| “ | Pierlot and his government saw that Western Europe had been conquered by the Germans completely and tried to make amends to their king. Would it be possible for them to return to Belgium and form a new government? Leopold showed his stubborn nature; he was insulted by his ministers... His reply was short: 'The situation of the King is unaltered; he does not engage in politics and does not receive politicians.' | ” |

Because of the great popularity of the king, and the unpopularity of the civil government from the middle of 1940, the government crisis persisted. The Royal Articles state:

| “ | This refusal [of the King to reconcile with the ministers] left the ministers with no other option than to move to London, where they could continue their work representing the independent Belgium. From the time of their arrival in London, they were confident about an Allied victory and soon were treated with respect by the Allies.... Pierlot and Spaak helped to build Leopold's reputation as a heroic prisoner of war and even said that the Belgians should support their King. But they had no idea what Leopold was doing in [the Royal Palace at] Laeken. He refused to reply to their messages and stayed cool toward them. What was he doing in the castle? Was he collaborating, did he oppose the Germans, or had he decided to just shut his mouth and wait to see how things would go? | ” |

On 2 August 1940, several ministers conferred in Le Perthus near the Spanish border. Prime Minister Pierlot and Foreign Minister Paul - Henri Spaak were persuaded to go to London; but they were able to start only at the end of August, and could travel only via neutral Spain and Portugal. When they reached Spain, they were arrested and detained by the Franco regime; they arrived finally in London on 22 October.

Leopold rejected cooperation with the Nazis and

refused to administer Belgium in accordance with their dictates, and

the Germans implemented a military government. Leopold attempted to

assert his authority as monarch and head of the Belgian government

although he was a prisoner of the Germans. Despite his defiance of the

Germans, the Belgian government - in - exile in London maintained that the

king did not represent the Belgian government and was unable to reign.

The Germans held him at first under house arrest at the Royal Castle in Brussels. Having desired a meeting with Adolf Hitler since

June 1940, Leopold III finally met with him on 19 November 1940.

Leopold wanted Hitler to issue a public statement about Belgium's future independence. Hitler's vision of a united Europe did

not include independent countries within its borders. Hitler refused to

speak about the independence of Belgium or issue a statement about it.

In refusing to publish the statement, Hitler unintentionally preserved

the King from being seen as cooperating with Germany, and thus engaged

in treasonous acts, which would have likely meant he was forced to

abdicate after the war. "The [German] Chancellor saved the King two

times."

On 11 September 1941, while a prisoner of the Germans, Leopold secretly married Lilian Baels in a religious ceremony that had no validity under Belgian law, as Belgian law required a religious marriage to be preceded by a legal or civil marriage. On 6 December, they were married under civil law. The reason for the out - of - order marriages was not made public, but they had a child seven months later in June 1942. It would have been unacceptable for a King of the Belgians to have maintained an "unofficial" relationship with Lilian.

Cardinal Jozef - Ernest van Roey, Archbishop of Mechelen,

wrote an open letter to parish priests throughout the country

announcing Leopold's second marriage on December 7. The letter revealed

that the king's new wife would be known as Princesse de Réthy,

not Queen Lilian, and that any children they had would have no claim to

the throne (though they would be Princes or Princesses of Belgium with

the style Royal Highness). Leopold's new marriage damaged his reputation

further in the eyes of many of his subjects.

The ministers made several efforts during the war to work out a suitable agreement with Leopold III. They sent Pierlot's son - in - law as an emissary to Leopold in January 1944, carrying a letter offering reconciliation from the Belgian government in exile. The letter never reached its destination, however, as the son - in - law was killed by the Germans en route. The ministers did not know what happened to either message or messenger, and assumed Leopold was ignoring them.

Leopold wrote his Political Testament in January 1944 shortly after this failed attempt at reconciliation. The testament was to be published in case he was not in Belgium when Allied forces arrived. The testament, which had an imperious and negative tone, considered the potential Allied movement into Belgium an "occupation", not a "liberation". It gave no credit to the active Belgian resistance. The Belgian government in London did not like Leopold's demand that the government ministers involved in the 1940 crisis be exonerated. The Allies did not like Leopold's repudiation of the treaties concluded by the Belgian government - in - exile in London. The United States was particularly concerned about the economic treaty it had reached with the Belgian government in London that enabled them to obtain Congolese uranium for America's secret atom bomb program.

The Belgian government did not publish the Political Testament and tried to ignore it, partly for fear of increased support for the Belgian Communist party. When Pierlot and Spaak learned of its contents in September 1944, they were astonished and felt deceived by the king. According to André de Staercke, the Regent's Secretary, they were dismayed "in the face of so much blindness and awareness".

Churchill's reaction to the Testament: "It stinks." In a sentence inspired by a quote of Talleyrand about the Bourbons after the restoration of the French monarchy in 1815, Churchill declared: "He is like the Bourbons, he has learned nothing and forgotten everything."

In 1944, Heinrich Himmler ordered Leopold deported to Germany. Princess Liliane followed with the family in another car the following day under an SS armed guard. The Nazis held the family in a fort at Hirschstein in Saxony from June 1944 to March 1945, and then at Strobl, Austria.

The British and American governments worried about the return of the king. Leopold III was prisoner of the Germans. Though all knew in March 1945 of the future capitulation of Germany, nobody knew Leopold's location in Germany. Charles W. Sawyer, US Ambassador to Belgium, warned his government that an immediate return by the king to Belgium would "precipitate serious difficulties." "There are deep differences even in the Royal family and the situation holds dynamite for Belgium and perhaps for Europe." "The Foreign Office feared that an increasing minority in French speaking Wallonia would demand either autonomy or annexation to France. Winant, the American Ambassador to the Court of Saint James's, reported a Foreign Office official's concern regarding irredentist propaganda in Wallonia." and that "the French Ambassador in Brussels... is believed to have connived in the spreading of this propaganda."

Leopold and his companions were freed by members of the United States 106th Cavalry Group in

early May 1945. Because of the controversy about his conduct during the

war, Leopold III and his wife and children were unable to return to

Belgium and spent the next six years in exile at Pregny - Chambésy near Geneva, Switzerland. A regency under his brother Prince Charles had been established by the Legislature in 1944.

Van den Dungen, the rector of the Université Libre de Bruxelles wrote to Leopold on 25 June 1945 about concerns for serious disorder in Wallonia, "The question is not if the accusations against you are right or not [but that...] You are no more a symbol of the Belgian unity."

Gilllon, the President of the Belgian Senate, told the king that there was a threat of serious disorder: "If there are only ten or twenty people killed, the situation would become terrible for the King.".

The President of the Belgian Chamber of Representatives, Frans Van Cauwelaert, was concerned that there would be a General strike in Wallonia and revolt in Liège. He wrote, "The country is not able to put down the disorders because of the insufficient forces of the police and a lack of weapons."

In 1946, a commission of inquiry exonerated Leopold of treason. Nonetheless, controversy concerning his loyalty continued, and in 1950, a referendum was held about his future. Fifty - seven per cent of the voters favored his return. The divide between Leopoldists and anti - Leopoldists ran along the lines of socialists and Walloons who were mostly opposed (42% favorable votes in Wallonia) and Christian Democrats and Flemings who were more in favor of the King (70% favorable votes in Flanders).

On his return to Belgium in 1950, Leopold was met with one of the most violent general strikes in the history of Belgium. Three protesters were killed when the gendarmerie opened

automatic fire upon the protesters. The country stood on the brink of

civil war, and Belgian banners were replaced by Walloon flags in Liège and other municipalities of Wallonia. To

avoid tearing the country apart, and to preserve the monarchy, Leopold

decided on 1 August 1950 to withdraw in favor of his 20 year old son Baudouin.

His abdication took effect on 16 July 1951, though in reality the

government had already forced the issue on 1 August 1950. In this postponed abdication the king was, in effect, forced by the government of Jean Duvieusart to offer to abdicate in favor of his son. Leopold

and his wife continued to advise King Baudouin until the latter's

marriage in 1960. Some Belgian historians, such as Vincent Delcorps,

speak of there having been a "dyarchy" during this period.

In retirement, he followed his passion as an amateur social anthropologist and entomologist and traveled the world. He went, for instance, to Senegal and strongly criticized the French decolonization process, and he explored the Orinoco and the Amazon with Heinrich Harrer.

Leopold died in 1983 at Woluwe - Saint - Lambert (Sint - Lambrechts - Woluwe). He is interred next to Queen Astrid (and also later his second wife, The Princess de Réthy was interred with them) in the royal vault at the Church of Our Lady of Laeken.