<Back to Index>

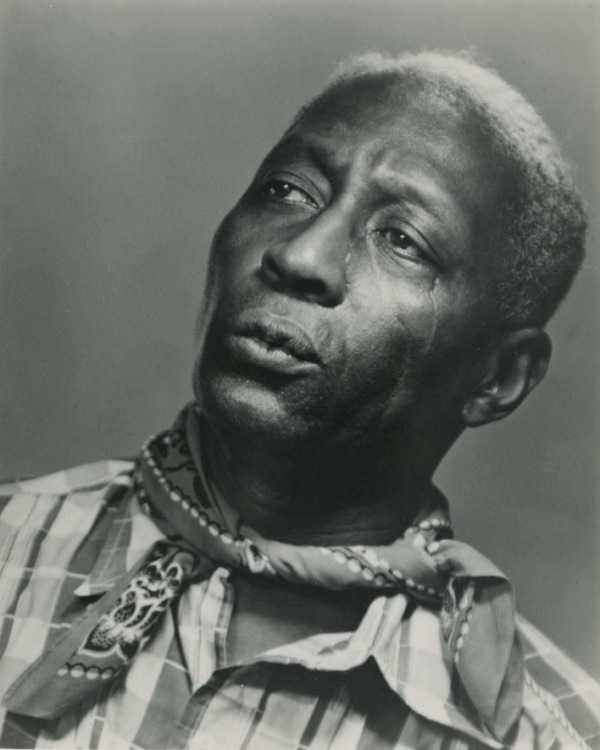

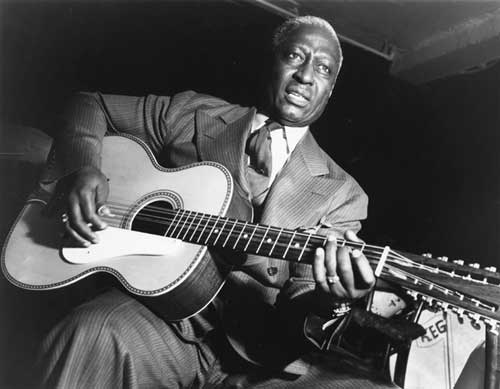

- Bluesman Huddie William "Lead Belly" Ledbetter, 1888

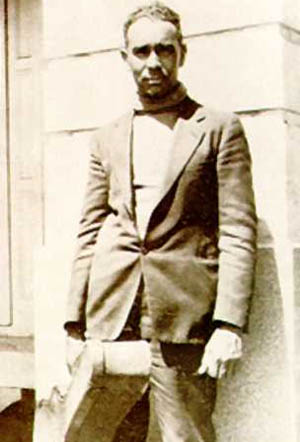

- Bluesman Charlie Patton, 1889

- Bluesman Armenter "Bo Carter" Chatmon, 1892

PAGE SPONSOR

Huddie William Ledbetter (January 20, 1888 – December 6, 1949) was an iconic American folk, blues musician, and multi - instrumentalist, notable for his strong vocals, his virtuosity on the twelve - string guitar, and the songbook of folk standards he introduced.

He is best known as Lead Belly. Though many releases list him as "Leadbelly", he himself spelled it "Lead Belly". This is also the usage on his tombstone, as well as of the Lead Belly Foundation. In 1994 the Lead Belly Foundation contacted an authority on the history of popular music, Colin Larkin, editor of the Encyclopedia of Popular Music, to ask if the name "Leadbelly" could be altered to "Lead Belly" in the hope that other authors would follow suit and use the artist's correct appellation.

Although Lead Belly most commonly played the twelve - string, he could also play the piano, mandolin, harmonica, violin and accordion. In some of his recordings, such as in one of his versions of the folk ballad "John Hardy", he performs on the accordion instead of the guitar. In other recordings he just sings while clapping his hands or stomping his foot.

The topics of Lead Belly's music covered a wide range of subjects, including gospel songs; blues songs about women, liquor and racism; and folk songs about cowboys, prison, work, sailors, cattle herding and dancing. He also wrote songs concerning the newsmakers of the day, such as Franklin D. Roosevelt, Adolf Hitler, Jean Harlow, the Scottsboro Boys and Howard Hughes.

In 2008, Lead Belly was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame.

Born Huddie William Ledbetter on the Jeter Plantation near Mooringsport, Louisiana, the younger of two children to Sallie Brown and Wesley Ledbetter. He had an older sister named Australia. "Huddie" is pronounced "HYEW-dee" or "HUGH-dee".

Ledbetter was probably born in January 1888, though his grave marker lists his birth date as January 23, 1889. The 1900 United States Census lists "Hudy William Ledbetter" as 12 years old, and his birth date as January 20, 1888. The 1910 United States Census and the 1930 United States Census also list his birth date as January 20, 1888. In April 1942, Ledbetter filled out his World War II draft registration, listing his birth date as January 23, 1889.

His parents married on February 26, 1888, but had cohabited for several years.

When Ledbetter was five years old, the family settled in Bowie County, Texas.

By 1903, Lead Belly was already a "musicianer", a singer and guitarist of some note. He performed for nearby Shreveport audiences in St. Paul's Bottoms, a notorious red light district there. Lead Belly began to develop his own style of music after exposure to a variety of musical influences on Shreveport's Fannin Street, a row of saloons, brothels and dance halls in the Bottoms.

At the time of the 1910 census, Lead Belly, still officially listed as "Hudy", was living next door to his parents with his first wife, Aletha "Lethe" Henderson, who at the time of the census was 17 years old, and was, therefore, 15 at the time of their marriage in 1908. It was also there that he received his first instrument, an accordion, from his uncle, and by his early 20s, after fathering at least two children, he left home to find his living as a guitarist (and occasionally as a laborer).

Influenced by the sinking of the RMS Titanic in April 1912, he wrote the song "The Titanic",

which noted the racial differences of the time. "The Titanic" was the

first song he ever learned to play on a 12 string guitar, which was

later to become his signature instrument. He first played it in 1912

when performing with Blind Lemon Jefferson (1897 – 1929) in and around Dallas, Texas. The song is about champion African - American boxer Jack Johnson's being denied passage on the Titanic due to his race — in point of fact, although Johnson was denied passage on a ship for being black, he was not denied entrance to the Titanic — with the iconic line, "Jack Johnson tried to get on board. The Captain, he says, 'I ain't haulin' no coal!' Fare thee, Titanic! Fare thee well!" Lead Belly noted that he had to leave out this verse when playing in front of white audiences.

Ledbetter's volatile temper sometimes led him into trouble with the law. In 1915 he was convicted "of carrying a pistol" and sentenced to do time on the Harrison County chain gang, from which he escaped, finding work in nearby Bowie County under the assumed name of Walter Boyd. In January 1918 he was imprisoned a second time, this time after killing one of his relatives, Will Stafford, in a fight over a woman. In 1918 he was incarcerated in Sugar Land west of Houston, Texas, where he probably learned the song "Midnight Special". He served time in the Imperial Farm (now Central Unit) in Sugar Land. In 1925 he was pardoned and released, having served seven years, or virtually all of the minimum of his seven - to - 35 year sentence, after writing a song appealing to Governor Pat Morris Neff for his freedom. Ledbetter had swayed Neff by appealing to his strong religious beliefs. That, in combination with good behavior (including entertaining by playing for the guards and fellow prisoners), was Ledbetter's ticket out of prison. It was quite a testament to his persuasive powers, as Neff had run for governor on a pledge not to issue pardons (pardon by the governor was at that time the only recourse for prisoners, since in most Southern prisons there was no provision for parole). According to Charles K. Wolfe and Kip Lornell's book, The Life and Legend of Leadbelly (1999), Neff had regularly brought guests to the prison on Sunday picnics to hear Ledbetter perform.

In 1930, Ledbetter was back in prison, after a summary trial, this time in Louisiana, for attempted homicide — he had knifed a white man in a fight. It was there, three years later (1933), that he was "discovered" by folklorists John Lomax and his then 18 year old son Alan Lomax during a visit to the Angola Prison Farm. Deeply impressed by his vibrant tenor voice and huge repertoire, they recorded him on portable aluminum disc recording equipment for the Library of Congress. They returned to record with new and better equipment in July of the following year (1934), all in all recording hundreds of his songs. On August 1, Lead Belly was released (again having served almost all of his minimum sentence), this time after the Lomaxes had taken a petition to Louisiana Governor Oscar K. Allen at Ledbetter's urgent request. The petition was on the other side of a recording of his signature song, "Goodnight Irene". A prison official later wrote to John Lomax denying that Ledbetter's singing had anything to do with his release from Angola, and state prison records confirm that he was eligible for early release due to good behavior. For a time, however, both Ledbetter and the Lomaxes believed that the record they had taken to the governor had hastened his release from Angola.

Bob Dylan once remarked, on his XM radio show, that Ledbetter was "one of the few ex-cons who recorded a popular children’s album".

There are several somewhat conflicting stories about how Ledbetter

acquired his famous nickname, though the consensus is that it was

probably while in prison. Some say his fellow inmates dubbed him "Lead

Belly" as a play on his last name and reference to his physical

toughness; others say he earned the name after being shot in the stomach

with shotgun buckshot. Another theory has it that the name refers to his ability to drink moonshine, homemade liquor which Southern farmers, black and white, used to make to supplement their incomes. Blues singer Big Bill Broonzy

thought it came from a supposed tendency to lay about as if "with a

stomach weighted down by lead" in the shade when the chain gang was

supposed to be working.

(This seems unlikely, unless it was ironic, given his well known

capacity for hard work.) It is likely that it is simply a corruption of

his surname pronounced with a southern accent. Whatever its origin, he

adopted the nickname as a pseudonym while performing, and it stuck.

Regarding his toughness, it is also recounted that during his second

prison term, another inmate stabbed him in the neck (leaving him with a

fearsome scar that he subsequently covered with a bandana), and he took

the knife away and in turn almost killed his attacker with it.

By the time Lead Belly was released from prison, the United States was deep in the Great Depression and jobs were very scarce. In September 1934, in need of regular work in order to avoid having his release canceled, Lead Belly met with John A. Lomax and asked him to take him on as a driver. For three months he assisted the 67 year old John Lomax in his folk song collecting in the South. (Alan Lomax was ill and did not accompany them on this trip.)

In December, Lead Belly participated in a "smoker" (group sing) at an MLA meeting in Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, where John A. Lomax had a prior lecturing engagement. He was written up in the press as a convict who had sung his way out of prison. On New Year's Day, 1935, the pair arrived in New York City, where John Lomax was scheduled to meet with his publisher, Macmillan, about a new collection of folk songs. The newspapers were eager to write about the "singing convict" and Time magazine made one of its first filmed March of Time newsreels about him. Lead Belly attained fame (though not fortune).

The following week, he began recording with ARC, the race records division of Columbia Records, but these recordings achieved little commercial success. Part of the reason for the poor sales may have been because ARC insisted on releasing only his blues songs rather than the folk songs for which he would later become better known. In any case, Lead Belly continued to struggle financially. Like many performers, what income he made during his lifetime would come from touring, not from record sales.

In February 1935, he married his girlfriend, Martha Promise, who came north from Louisiana to join him.

The month of February was spent recording his and other African - American repertoire and interviews about his life with Alan Lomax for their forthcoming book, Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly (1936). Concert appearances were slow to materialize, however, and in March 1935, Lead Belly accompanied John A. Lomax on a two week lecture tour of colleges and universities in the Northeast, culminating at Harvard. These lectures had been scheduled before John Lomax had teamed up with Lead Belly.

At the end of the month, John Lomax decided he could no longer work with Lead Belly and gave him and Martha money to go back to Louisiana by bus. He gave Martha the money that Lead Belly had earned from three months of performing, but in installments, on the pretext that Lead Belly would drink it all if given a lump sum. From Louisiana, Lead Belly then successfully sued Lomax for the full amount and for release from his management contract with Lomax. The quarrel was very bitter and there were hard feelings on both sides. Curiously, however, in the midst of the legal wrangling Lead Belly wrote to John A. Lomax proposing that they team up together once again. It was not to be, however. The book about Lead Belly that the Lomaxes published in the fall of the following year, meanwhile, was a commercial failure.

In January 1936, Lead Belly returned to New York on his own without John Lomax for an attempted comeback. He performed twice a day at Harlem's Apollo Theater during the Easter season in a live dramatic recreation of the Time Life newsreel (itself a recreation) about his prison encounter with John A. Lomax, in which he had worn stripes, even though by this time he was no longer associated with Lomax.

Life magazine ran a three page article titled, "Lead Belly - Bad Nigger Makes Good Minstrel", in the April 19, 1937 issue. It included a full page, color (rare in those days) picture of him sitting on grain sacks playing his guitar and singing. Also included was a striking picture of Martha Promise (identified in the article as his manager); photos showing Lead Belly's hands playing the guitar (with the caption "these hands once killed a man"); Texas Governor Pat M. Neff; and the "ramshackle" Texas State Penitentiary. The article attributes both of his pardons to his singing of his petitions to the governors, who were so moved that they pardoned him. The article's text ends with "he... may well be on the brink of a new and prosperous period".

Lead Belly failed to stir the enthusiasm of Harlem audiences. Instead, he attained success playing at concerts and benefits for an audience of leftist folk music aficionados. He developed his own style of singing and explaining his repertoire in the context of Southern black culture, taking the hint from his previous participation in John A. Lomax's college lectures. He was especially successful with his repertoire of children's game songs (as a younger man in Louisiana he had sung regularly at children's birthday parties in the black community). He was written up as a heroic figure by the black novelist, Richard Wright, then a member of the Communist Party, in the columns of the Daily Worker, of which Wright was the Harlem editor. The two men became personal friends, though Lead Belly himself was apolitical — if anything, a supporter of Wendell Willkie, the centrist Republican candidate, for whom he wrote a campaign song.

In 1939, Lead Belly was back in jail for assault, after stabbing a man in a fight in Manhattan. Alan Lomax, then 24, took him under his wing and helped raise money for his legal expenses, dropping out of graduate school to do so. After his release (in 1940 - 41), Lead Belly appeared as a regular on Alan Lomax and Nicholas Ray's groundbreaking CBS radio show, Back Where I Come From, broadcast nationwide. He also appeared in night clubs with Josh White, becoming a fixture in New York City's surging folk music scene and befriending the likes of Sonny Terry, Brownie McGhee, Woody Guthrie, and a young Pete Seeger, all fellow performers on Back Where I Come From. During the first half of the decade he recorded for RCA, the Library of Congress, and for Moe Asch (future founder of Folkways Records), and in 1944 headed to California, where he recorded strong sessions for Capitol Records. Lead Belly was the first American country blues musician to see success in Europe.

In 1949 Lead Belly had a regular radio broadcast on station WNYC in New York on Sunday nights on Henrietta Yurchenko's show. Later in the year he began his first European tour with a trip to France, but fell ill before its completion, and was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig's disease. His final concert was at the University of Texas in a tribute to his former mentor, John A. Lomax, who had died the previous year. Martha also performed at that concert, singing spirituals with her husband.

Lead Belly died later that year in New York City, and was buried in

the Shiloh Baptist Church cemetery in Mooringsport, 8 miles (13 km) west

of Blanchard, in Caddo Parish. He is honored with a life size statue across from the Caddo Parish Courthouse in Shreveport.

Lead Belly styled himself "King of the 12 string guitar", and despite his use of other instruments like the accordion, the most enduring image of Lead Belly as a performer is wielding his unusually large Stella twelve string. This guitar had a slightly longer scale length than a standard guitar, slotted tuners, ladder bracing, and a trapeze style tailpiece to resist bridge lifting.

Lead Belly played with finger picks much of the time, using a thumb pick to provide a walking bass line and occasionally to strum. This technique, combined with low tunings and heavy strings, gives many of his recordings a piano like sound. Lead Belly's tuning is debated, but appears to be a downtuned variant of standard tuning; more than likely he tuned his guitar strings relative to one another, so that the actual notes shifted as the strings wore. Lead Belly's playing style was popularized by Pete Seeger, who adopted the twelve string guitar in the 1950s and released an instructional LP and book using Lead Belly as an exemplar of technique.

In some of the recordings where Lead Belly accompanied himself, he would make an unusual type of grunt between his verses, best described as "Haah!" Many of his songs, such as, "Looky Looky Yonder", "Take this Hammer", "Linin' Track" and "Julie Ann Johnson" feature this unusual vocalization. Lead Belly explained that, "Every time the men say 'haah', the hammer falls. The hammer rings, and we swing, and we sing", an apparent reference to prisoners' work songs. The "haah" sound can be heard in the work chants sung by Southern railroad section workers, "gandy dancers", where it was used to coordinate the crews as they laid and maintained the tracks before modern machinery was available.

Lead Belly has been covered by Delaney Davidson, Tom Russell, Lonnie Donegan, The Beach Boys, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Abba, Pete Seeger, Harry Belafonte, Ram Jam, Johnny Cash, Tom Petty, Dr John, Ry Cooder, Grateful Dead, Gene Autry, Odetta, Billy Childish (who named his son Huddie), Mungo Jerry, Paul King, Led Zeppelin, Van Morrison, Michelle Shocked, Tom Waits, Scott H. Biram, Ron Sexsmith, British Sea Power, Rod Stewart, Ernest Tubb, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, The White Stripes, The Fall, The Doors, Smog, Old Crow Medicine Show, Spiderbait, Meat Loaf, Yirmyah Fox, Ministry, Raffi, Rasputina, Rory Gallagher, the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, Deer Tick, Hugh Laurie, X, jazz guitarist Bill Frisell, Koerner, Ray & Glover, Nirvana, Mark Lanegan, WZRD, and Tyvek Velvette, among many others.

Charlie Patton (between April 1887 and 1891 – April 28, 1934), better known as Charley Patton, was an American Delta blues musician.

He is considered by many to be the "Father of the Delta Blues", and is

credited with creating an enduring body of American music and personally

inspiring just about every Delta blues man. Musicologist

Robert Palmer

considers him among the most important musicians that America produced

in the twentieth century. Many sources, including musical releases and

his gravestone, spell his name “Charley” even though the musician himself spelled his name "Charlie."

Patton was born in Hinds County, Mississippi, near the town of Edwards, and lived most of his life in Sunflower County in the Mississippi Delta. Most sources say he was born in 1891, but there is some debate about this, and the years 1887 and 1894 have also been suggested.

Patton's parentage and race have been the subject of minor debate. Although born to Bill and Annie Patton, locally he was regarded as having been fathered by former slave Henderson Chatmon, many of whose other children also became popular Delta musicians both as solo acts and as members of groups such as the Mississippi Sheiks. Biographer John Fahey describes Patton as having "light skin and Caucasian features." Though Patton was considered African - American, because of his light complexion there have been rumors that he was Mexican, or possibly a full - blood Cherokee, a theory endorsed by Howlin' Wolf. In actuality, Patton was a mix of white, black, and Cherokee (one of his grandmothers was a full - blooded Cherokee). Patton himself sang in "Down the Dirt Road Blues" of having gone to "the Nation" and "the Territo'" — meaning the Cherokee Nation portion of the Indian Territory (which became part of the state of Oklahoma in 1907), where a number of Black Indians tried unsuccessfully to claim a place on the tribal rolls and thereby obtain land.

In 1900, his family moved 100 miles (160 km) north to the legendary 10,000 acre (40 km2) Dockery Plantation sawmill and cotton farm near Ruleville, Mississippi. It was here that both John Lee Hooker and Howlin' Wolf fell under the Patton spell. It was also here that Robert Johnson played and was given his first guitar. At Dockery, Charlie fell under the tutelage of Henry Sloan, who had a new, unusual style of playing music which today would be considered very early blues. Charlie followed Henry Sloan around, and, by the time he was about 19, had become an accomplished performer and songwriter in his own right, having already composed "Pony Blues," a seminal song of the era.

Robert Palmer describes Patton as a "jack - of all - trades bluesman" who played "deep blues, white hillbilly songs, nineteenth century ballads, and other varieties of black and white country dance music with equal facility". He was extremely popular across the Southern United States and also performed annually in Chicago, Illinois, and, in 1934, New York City. In contrast to the itinerant wandering of most blues musicians of his time, Patton played scheduled engagements at plantations and taverns. Long before Jimi Hendrix impressed audiences with flashy guitar playing, Patton gained notoriety for his showmanship, often playing with the guitar down on his knees, behind his head, or behind his back. Although Patton was a small man at about 5 foot 5, his gravelly voice was rumored to have been loud enough to carry 500 yards without amplification. Patton's gritty bellowing was a major influence on the singing style of his young friend Chester Burnett, who went on to gain fame in Chicago as Howlin' Wolf.

Patton settled in Holly Ridge, Mississippi, with his common law wife and recording partner Bertha Lee in 1933. He died on the Heathman - Dedham plantation near Indianola

on April 28, 1934 and is buried in Holly Ridge (both towns are located

in Sunflower County). Patton's death certificate states that he died of a

mitral valve

disorder. Bertha Lee is not mentioned on the certificate, the only

informant listed being one Willie Calvin. His death was not reported in

the newspapers.

A memorial headstone was erected on Patton's grave (the location of

which was identified by the cemetery caretaker C. Howard who claimed to

have been present at the burial) paid for by musician John Fogerty through the Mt. Zion Memorial Fund in July, 1990. The spelling of Patton's name was dictated by Jim O'Neal who also composed the Patton epitaph.

Screamin' and Hollerin' the Blues: The Worlds of Charley Patton (2001) is a boxed set collecting Patton's recorded works. It also featured recordings by many of his friends and associates. The set won three Grammy Awards in 2003 for Best Historical Album, Best Boxed or Special Limited Edition Package, and Best Album Notes. Another collection of Patton recordings, released under Catfish Records is titled The Definitive Charley Patton.

Charley Patton's song "Pony Blues" (1929) was included by the National Recording Preservation Board in the Library of Congress' National Recording Registry in 2006. The board selects songs in an annual basis that are "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

The Mississippi Blues Trail placed its first historic marker on Charlie Patton's grave in Holly Ridge, Mississippi, in recognition of his legendary status as a bluesman and his importance in the development of the blues in Mississippi. It placed another historic marker at the site where the Peavine Railroad intersects with Highway 446 in Boyle, Mississippi, designating it as a second site related to Patton on the Mississippi Blues Trail. The marker commemorates the original lyrics of Patton's "Peavine Blues" which describes the railway branch of Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad which ran south from Dockery Plantation to Boyle. The marker emphasizes that a common theme of blues songs was riding on the railroad which was seen as a metaphor for travel and escape.

Armenter "Bo Carter" Chatmon (June 30, 1892 – September 21, 1964) was an American early blues musician. He was a member of the Mississippi Sheiks in concerts, and on a few of their recordings. Carter also managed that group, which included his brother, Lonnie Chatmon, on fiddle and occasionally Sam Chatmon on bass, along with a friend, Walter Vincson, on guitar and lead vocals.

Since the 1960s, Carter has become best known for his bawdy songs such as "Banana in Your Fruit Basket", "Pin in Your Cushion", "Your Biscuits Are Big Enough for Me", "Please Warm My Wiener" and "My Pencil Won't Write No More". However, his output was not restricted to risqué music. In 1928, he recorded the original version of "Corrine, Corrina", which later became a hit for Big Joe Turner and has become a standard in various musical genres.

Carter and his brothers (including pianist Harry Chatmon, who also made recordings), first learned music from their father, ex-slave fiddler Henderson Chatmon, at their home on a plantation between Bolton and Edwards, Mississippi. Their mother, Eliza, also sang and played guitar.

Carter made his recording debut in 1928, backing Alec Johnson. Carter soon was recording as a solo artist and became one of the dominant blues recording acts of the 1930s, recording 110 sides. He also played with and managed the family group, the Mississippi Sheiks, and several other acts in the area. He and the Sheiks often played for whites, playing the pop hits of the day and white oriented dance material, as well as for blacks, using a bluesier repertoire.

Carter went partly blind during the 1930s. He settled in Glen Allen and despite his vision problems did some farming but also continued to play music and perform, sometimes with his brothers. Carter moved to Memphis, and worked outside the music industry in the 1940s.

Carter suffered strokes and died of a cerebral hemorrhage at Shelby County Hospital, Memphis, on September 21, 1964.