<Back to Index>

This page is sponsored by:

PAGE SPONSOR

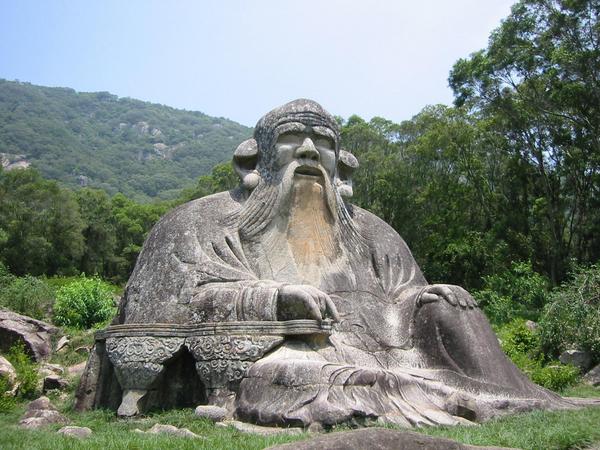

Laozi (Chinese: 老子; pinyin: Lǎozǐ; Wade–Giles: Lao Tzu; also romanized as Lao Tse, Lao Tu, Lao-Tsu, Laotze, Laosi, Laocius, and other variations) was a philosopher of ancient China, best known as the author of the Tao Te Ching (often simply referred to as Laozi). His association with the Tao Te Ching has led him to be traditionally considered the founder of philosophical Taoism (pronounced as "Daoism"). He is also revered as a deity in most religious forms of Taoist philosophy, which often refers to Laozi as Taishang Laojun, or "One of the Three Pure Ones".

According to Chinese traditions, Laozi lived in the 6th century BCE. Historians variously contend that Laozi is a synthesis of multiple historical figures, that he is a mythical figure, or that he actually lived in the 5th – 4th century BCE, concurrent with the Hundred Schools of Thought and Warring States Period.

A central figure in Chinese culture, both nobility and common people claim Laozi in their lineage. He was honored as an ancestor of the Tang imperial family, and was granted the title Taishang xuanyuan huangdi, meaning "Supreme Mysterious and Primordial Emperor". Xuanyuan and Huangdi are also, respectively, the personal and proper names of the Yellow Emperor. Throughout history, Laozi's work has been embraced by various anti - authoritarian movements.

Laozi is an honorific title. Lao (老) means "venerable" or "old", such as modern Mandarin laoshi (老师), "teacher". Zi (子), Wade - Giles transliteration tzu, in this context is typically translated "master". Zi

was used in ancient China as an honorific suffix, indicating "Master",

or "Sir". In popular biographies, Laozi's given name was Er, his surname

was Li (forming Li Er, 李耳) and his courtesy name was Boyang. Dan is a posthumous name given to Laozi, and he is sometimes referred to as Li Dan (李聃).

The earliest reliable reference (circa 100 BCE) to Laozi is found in the Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) by Chinese historian Sima Qian (ca. 145 – 86 BCE), which combines a number of stories. In the first, Laozi was said to be a contemporary of Confucius (551 – 479 BCE). His surname was Li (李 "plum"), and his personal name was Er (耳 "ear") or Dan (聃 "long ear"). He was an official in the imperial archives, and wrote a book in two parts before departing to the West. In the second, Laozi was Lao Laizi (老來子 "Old Master"), also a contemporary of Confucius, who wrote a book in 15 parts. In the third, Laozi was the Grand Historian and astrologer Lao Dan (老聃 "Old Long-ears"), who lived during the reign (384 – 362 BCE) of Duke Xian (獻公) of Qin).

By the mid twentieth century a consensus had emerged among scholars that the historicity of Laozi was doubtful or unprovable and that the Tao Te Ching was "a compilation of Taoist sayings by many hands." The oldest known text of the Tao Te Ching that's been excavated, written on bamboo tablets, dates back to the late 4th century BC. Alan Watts (1975) held that this view was part of an academic fashion for skepticism about historical spiritual and religious figures, arguing that not enough would be known for years, or possibly ever, to make a firm judgment.

According to popular traditional biographies, he worked as the Keeper of the Archives for the royal court of Zhou. This reportedly allowed him broad access to the works of the Yellow Emperor and other classics of the time. The stories assert that Laozi never opened a formal school, but he nonetheless attracted a large number of students and loyal disciples. There are numerous variations of a story depicting Confucius consulting Laozi about rituals and the story is related in Zhuangzi (though the author of Zhuangzi may have invented both the story and the character of Laozi).

Popular legends tell of his conception when his mother gazed upon a falling star, how he stayed in the womb for 62 years, and was born when his mother leaned against a plum tree. He accordingly emerged a grown man with a full grey beard and long earlobes, which are a symbol of wisdom and long life. In other versions he was reborn in some thirteen incarnations since the days of Fuxi; in his last incarnation as Laozi he lived to nine hundred and ninety years, and spent his life traveling to reveal the Dao.

Many of the popular accounts say that Laozi was married and had a son

named Zong, who became a celebrated soldier. A large number of people

trace their lineage back to Laozi, as did the emperors of the Tang Dynasty.

According to Simpkins & Simpkins, while many (if not all) of the

lineages are inaccurate, they provide a testament to the impact of Laozi

on Chinese culture.

The third story Sima Qian drew on states that Laozi grew weary of the moral decay of city life and noted the kingdom's decline. According to these legends, he ventured west to live as a hermit in the unsettled frontier at the age of 160. At the western gate of the city, or kingdom, he was recognized by a guard, Yinxi (Wade Giles Yin Hse).

The sentry asked the old master to produce a record of his wisdom. This is the legendary origin of the Daodejing. In some versions of the tale, the sentry is so touched by the work that he leaves with Laozi, never to be seen again. Some legends elaborate further that the "Old Master" was the teacher of the Siddartha Gautama, better known as the Buddha, or was even the Buddha himself.

Laozi's relationship with Yinxi is the subject of numerous legends.

It is Yinxi who asked Laozi to write down his wisdom in the traditional

account of the Daodejing's creation. The story of Laozi transmitting the Daodejing

to Yinxi is part of a broader theme involving Laozi the deity

delivering salvific truth to a suffering humanity. Regardless, the

deliverance of the Daodejing was the ultimate purpose of his human

incarnation. Folklore developed around Laozi and Yinxi to demonstrate

the ideal interaction of Taoist master and disciple.

A seventh century work, Sandong zhunang ("Pearly Bag of the Three Caverns"), provides one account of their relationship. Laozi pretended to be a farmer when reaching the western gate, but was recognized by Yinxi, who asked to be taught by the great master. Laozi was not satisfied by simply being noticed by the guard and demanded an explanation. Yinxi expressed his deep desire to find the Tao and explained that his long study of astrology allowed him to recognize Laozi's approach. Yinxi was accepted by Laozi as a disciple. This is considered an exemplary interaction between Daoist master and disciple, reflecting the testing a seeker must undergo before being accepted. A would be adherent is expected to prove his determination and talent, clearly expressing his wishes and showing that he had made progress on his own towards realizing the Tao.

The Pearly Bag of the Three Caverns continues the parallel of an adherent's quest. Yinxi received his ordination when Laozi transmitted the Daodejing, along with other texts and precepts, just as Taoist adherents receive a number of methods, teachings and scriptures at ordination. This is only an initial ordination and Yinxi still needed an additional period to perfect his faith, thus Laozi gave him three years to perfect his Dao. Yinxi gave himself over to a full time devotional life. After the appointed time, Yinxi again demonstrates determination and perfect trust, sending out a black sheep to market as the agreed sign. He eventually meets again with Laozi, who announces that Yinxi's immortal name is listed in the heavens and calls down a heavenly procession to clothe Yinxi in the garb of immortals. The story continues that Laozi bestowed a number of titles upon Yinxi and took him on a journey throughout the universe, even into the nine heavens. After this fantastic journey, the two sages set out to western lands of the barbarians. The training period, reuniting and travels represent the attainment of the highest religious rank in medieval Taoism called "Preceptor of the Three Caverns". In this legend, Laozi is the perfect Daoist master and Yinxi is the ideal Taoist student. Laozi is presented as the Tao personified, giving his teaching to humanity for their salvation. Yinxi follows the formal sequence of preparation, testing, training and attainment.

The story of Laozi has taken on strong religious overtones since the Han dynasty.

As Daoism took root, Laozi was recognized as a god. Belief in the

revelation of the Dao from the divine Laozi resulted in the formation of

the Way of the Celestial Master, the first organized religious Daoist sect. In later mature Daoist

tradition, Laozi came to be seen as a personification of Dao. He is said

to have undergone numerous "transformations", or taken on various

guises in various incarnations throughout history to initiate the

faithful in the Way. Religious Daoism often holds that the "Old Master"

did not disappear after writing the Daodejing, but rather spent his life traveling to reveal the Dao.

Laozi is traditionally regarded as the author of the Daodejing (Tao Te Ching), though the identity of its author(s) and/or compiler(s) has been debated throughout history. It is one of the most significant treatises in Chinese cosmogony. As with most other ancient Chinese philosophers, Laozi often explains his ideas by way of paradox, analogy, appropriation of ancient sayings, repetition, symmetry, rhyme, and rhythm.

The Tao Te Ching, often called simply Laozi after its reputed author, describes the Dao (or Tao) as the source and ideal of all existence: it is unseen, but not transcendent, immensely powerful yet supremely humble, being the root of all things. According to the Daodejing, humans have no special place within the Dao, being just one of its many ("ten thousand") manifestations. People have desires and free will (and thus are able to alter their own nature). Many act "unnaturally", upsetting the natural balance of the Dao. The Daodejing intends to lead students to a "return" to their natural state, in harmony with Dao. Language and conventional wisdom are critically assessed. Taoism views them as inherently biased and artificial, widely using paradoxes to sharpen the point.

Livia Kohn provides an example of how Laozi encouraged a change in approach, or return to "nature", rather than action. Technology may bring about a false sense of progress. The answer provided by Laozi is not the rejection of technology, but instead seeking the calm state of wu wei, free from desires. This relates to many statements by Laozi encouraging rulers to keep their people in "ignorance", or "simple - minded". Some scholars insist this explanation ignores the religious context, and others question it as an apologetic of the philosophical coherence of the text. It would not be unusual political advice if Laozi literally intended to tell rulers to keep their people ignorant. However, some terms in the text, such as "valley spirit" (gushen) and "soul" (po), bear a metaphysical context and cannot be easily reconciled with a purely ethical reading of the work.

Wu wei, literally "non - action" or "not acting", is a central concept of the Daodejing. The concept of wu wei is very complex and reflected in the words' multiple meanings, even in English translation; it can mean "not doing anything", "not forcing", "not acting" in the theatrical sense, "creating nothingness", "acting spontaneously", and "flowing with the moment."

It is a concept used to explain ziran,

or harmony with the Dao. It includes the concepts that value

distinctions are ideological and seeing ambition of all sorts as

originating from the same source. Laozi used the term broadly with simplicity and humility

as key virtues, often in contrast to selfish action. On a political

level, it means avoiding such circumstances as war, harsh laws and heavy

taxes. Some Taoists see a connection between wu wei and esoteric practices, such as the "sitting in oblivion" (emptying the mind of bodily awareness and thought) found in the Zhuangzi.

Laozi is traditionally regarded as the founder of Daoism, intimately connected with the Daodejing and "primordial" (or "original") Daoism. Popular ("religious") Daoism typically presents the Jade Emperor as the official head deity. Intellectual ("elite") Daoists, such as the Celestial Masters sect, usually present Laozi (Laojun, "Lord Lao") and the Three Pure Ones at the top of the pantheon of deities.

According to esoteric adherents, the book contains specific instructions for Daoist adepts relating to qigong meditations, and in veiled preachings the way to revert to the primordial state. This interpretation supports the view that Taoism is a religion addressing the quest of immortality.

Zhuangzi is a central authority regarding eremitism, a particular variation of monasticism sacrificing social aspects for religious aspects of life. Zhuangzi considered eremitism the highest ideal, if properly understood.

Scholars such as Aat Vervoom have postulated that Zhuangzi advocated a hermit immersed in society. This view of eremitism holds that seclusion is hiding anonymously in society. To a Zhuangzi hermit, being unknown and drifting freely is a state of mind. This reading is based on the "inner chapters" of the self - titled Zhuangzi.

Scholars such as James Bellamy hold that this could be true and has

been interpreted similarly at various points in Chinese history. However, the "outer chapters" of Zhuangzi have historically

played a pivotal role in the advocacy of reclusion. While some scholars

state that Laozi was the central figure of Han Dynasty eremitism,

historical texts do not seem to support that position.

Potential officials throughout Chinese history drew on the authority of non - Confucian sages, especially Laozi and Zhuangzi, to deny serving any ruler at any time. Zhuangzi, Laozi's most famous follower in traditional accounts, had a great deal of influence on Chinese literati and culture.

Political theorists influenced by Laozi have advocated humility in leadership and a restrained approach to statecraft, either for ethical and pacifist reasons, or for tactical ends. In a different context, various anti - authoritarian movements have embraced the Laozi teachings on the power of the weak.

The right libertarian economist Murray Rothbard suggested that Laozi was the first libertarian, likening Laozi's ideas on government to F.A. Hayek's theory of spontaneous order. James A. Dorn agreed, writing that Laozi, like many 18th century liberals, "argued that minimizing the role of government and letting individuals develop spontaneously would best achieve social and economic harmony." Similarly, the Cato Institute's David Boaz includes passages from the Daodejing in his 1997 book The Libertarian Reader. Philosopher Roderick Long, however, argues that libertarian themes in Taoist thought are actually borrowed from earlier Confucian writers.

Left libertarians have been highly influenced by Laozi as well. In his 1937 book Nationalism and Culture, the anarcho - syndicalist writer and activist Rudolf Rocker

praised Laozi's "gentle wisdom" and understanding of the opposition

between political power and the cultural activities of the people and

community. In his 1910 article for the Encyclopædia Britannica, Peter Kropotkin also noted that Laozi was among the earliest exponents of essentially anarchist concepts. More recently, anarchists such as John P. Clark and Ursula K. Le Guin

have written about the conjunction between anarchism and Taoism in

various ways, highlighting the teachings of Laozi in particular.

In her translation of the Tao Te Ching, Le Guin writes that Laozi "does

not see political power as magic. He sees rightful power as earned and

wrongful power as usurped... He sees sacrifice of self or others as a

corruption of power, and power as available to anyone who follows the

Way. No wonder anarchists and Taoists make good friends."

Zhuangzi (simplified Chinese: 庄子; traditional Chinese: 莊子; pinyin: Zhuāng Zǐ; Wade – Giles: Chuang Tzŭ) was an influential Chinese philosopher who lived around the 4th century BCE during the Warring States Period, a period corresponding to the philosophical summit of Chinese thought — the Hundred Schools of Thought, and is credited with writing — in part or in whole — a work known by his name, the Zhuangzi. His name Zhuangzi (English "Master Zhuang", with Zi being an honorific) is sometimes spelled Zhuang Tze, Zhuang Zhou, Chuang Tsu, Chuang Tzu, Chouang-Dsi, Chuang Tse, or Chuangtze.

The only account of the life of Zhuangzi is a brief sketch in chapter 63 of Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, where he is described as a minor official from the town of Meng (in modern Anhui) in the state of Song, living in the time of King Hui of Liang and King Xuan of Qi (late 4th century BCE). Sima Qian writes:

-

- Chuang - Tze had made himself well acquainted with all the literature of his time, but preferred the views of Lao - Tze; and ranked himself among his followers, so that of the more than ten myriads of characters contained in his published writings the greater part are occupied with metaphorical illustrations of Lao's doctrines. He made "The Old Fisherman," "The Robber Chih," and "The Cutting open Satchels," to satirize and expose the disciples of Confucius, and clearly exhibit the sentiments of Lao. Such names and characters as "Wei - lei Hsu" and "Khang - sang Tze" are fictitious, and the pieces where they occur are not to be understood as narratives of real events.

-

- But Chuang was an admirable writer and skilful composer, and by his instances and truthful descriptions hit and exposed the Mohists and Literati. The ablest scholars of his day could not escape his satire nor reply to it, while he allowed and enjoyed himself with his sparkling, dashing style; and thus it was that the greatest men, even kings and princes, could not use him for their purposes.

-

- King Wei of Chu, having heard of the ability of Chuang Chau, sent messengers with large gifts to bring him to his court, and promising also that he would make him his chief minister. Chuang - Tze, however, only laughed and said to them, "A thousand ounces of silver are a great gain to me; and to be a high noble and minister is a most honorable position. But have you not seen the victim - ox for the border sacrifice? It is carefully fed for several years, and robed with rich embroidery that it may be fit to enter the Grand Temple. When the time comes for it to do so, it would prefer to be a little pig, but it can not get to be so. Go away quickly, and do not soil me with your presence. I had rather amuse and enjoy myself in the midst of a filthy ditch than be subject to the rules and restrictions in the court of a sovereign. I have determined never to take office, but prefer the enjoyment of my own free will."

The validity of his existence has been questioned by some, including himself and Russell Kirkland, who writes:

According to modern understandings of Chinese tradition, the text known as the Chuang - tzu was the production of a 'Taoist' thinker of ancient China named Chuang Chou / Zhuang Zhou. In reality, it was nothing of the sort. The Chuang - tzu known to us today was the production of a thinker of the third century CE named Kuo Hsiang. Though Kuo was long called merely a 'commentator,' he was in reality much more: he arranged the texts and compiled the present 33 chapter edition. Regarding the identity of the original person named Chuang Chou / Zhuangzi, there is no reliable historical data at all.

However, Sima Qian's biography of Zhuangzi pre - dates Guo Xiang (d. 312 CE) by centuries. Furthermore, the Han Shu "Yiwen zhi" (Monograph on literature) lists a text Zhuangzi, showing that a text with this title existed no later than the early 1st century CE, again pre - dating Guo Xiang by centuries.

Zhuangzi is traditionally credited as the author of at least part of the work bearing his name, the Zhuangzi. This work, in its current shape consisting of 33 chapters, is traditionally divided into three parts: the first, known as the "Inner Chapters", consists of the first seven chapters; the second, known as the "Outer Chapters", consist of the next 15 chapters; the last, known as the "Mixed Chapters", consist of the remaining 11 chapters. The meaning of these three names is disputed: according to Guo Xiang, the "Inner Chapters" were written by Zhuangzi, the "Outer Chapters" written by his disciples, and the "Mixed Chapters" by other hands; the other interpretation is that the names refer to the origin of the titles of the chapters — the "Inner Chapters" take their titles from phrases inside the chapter, the "Outer Chapters" from the opening words of the chapters, and the "Mixed Chapters" from a mixture of these two sources.

Further study of the text does not provide a clear choice between these alternatives. On the one side, as Martin Palmer points out in the introduction to his translation, two of the three chapters Sima Qian cited in his biography of Zhuangzi, come from the "Outer Chapters" and the third from the "Mixed Chapters". "Neither of these are allowed as authentic Chuang Tzu chapters by certain purists, yet they breathe the very spirit of Chuang Tzu just as much as, for example, the famous 'butterfly passage' of chapter 2."

On the other hand, chapter 33 has been often considered as intrusive, being a survey of the major movements during the "Hundred Schools of Thought" with an emphasis on the philosophy of Hui Shih. Further, A.C. Graham and other critics have subjected the text to a stylistic analysis and identified four strains of thought in the book: a) the ideas of Zhuangzi or his disciples; b) a "primitivist" strain of thinking similar to Laozi; c) a strain very strongly represented in chapters 8-11 which is attributed to the philosophy of Yang Chu; and d) a fourth strain which may be related to the philosophical school of Huang - Lao. In this spirit, Martin Palmer wrote that "trying to read Chuang Tzu sequentially is a mistake. The text is a collection, not a developing argument."

Zhuangzi was renowned for his brilliant wordplay and use of parables to convey messages. His critiques of Confucian society and historical figures are humorous and at times ironic.

In general, Zhuangzi's philosophy is skeptical, arguing that life is limited and knowledge to be gained is unlimited. To use the limited to pursue the unlimited, he said, was foolish. Our language and cognition in general presuppose a dao to which each of us is committed by our separate past — our paths. Consequently, we should be aware that our most carefully considered conclusions might seem misguided had we experienced a different past. Zhuangzi argues that in addition to experience our natural dispositions are combined with acquired ones — including dispositions to use names of things, to approve / disapprove based on those names and to act in accordance to the embodied standards. Thinking about and choosing our next step down our dao or path is conditioned by this unique set of natural acquisitions.

Zhuangzi's thought can also be considered a precursor of relativism in systems of value. His relativism even leads him to doubt the basis of pragmatic arguments (that a course of action preserves our lives) since this presupposes that life is good and death bad. In the fourth section of "The Great Happiness" (至樂 zhìlè, chapter 18), Zhuangzi expresses pity to a skull he sees lying at the side of the road. Zhuangzi laments that the skull is now dead, but the skull retorts, "How do you know it's bad to be dead?"

Another example about two famous courtesans points out that there is no universally objective standard for beauty. This is taken from Chapter 2 (齊物論 qí wù lùn) "On Arranging Things", or "Discussion of Setting Things Right" or, in Burton Watson's translation, "Discussion on Making All Things Equal".

Men claim that Mao [Qiang] and Lady Li were beautiful, but if fish saw them they would dive to the bottom of the stream; if birds saw them they would fly away, and if deer saw them they would break into a run. Of these four, who knows how to fix the standard of beauty in the world? (2, tr. Watson 1968:46)

However, this subjectivism is balanced by a kind of sensitive holism in the famous section called "The Happiness of Fish" (魚之樂, yúzhīlè).

Zhuangzi and Huizi were strolling along the dam of the Hao Waterfall when Zhuangzi said, "See how the minnows come out and dart around where they please! That's what fish really enjoy!"Huizi said, "You're not a fish — how do you know what fish enjoy?"

Zhuangzi said, "You're not me, so how do you know I don't know what fish enjoy?"

Huizi said, "I'm not you, so I certainly don't know what you know. On the other hand, you're certainly not a fish — so that still proves you don't know what fish enjoy!"

Zhuangzi said, "Let's go back to your original question, please. You asked me how I know what fish enjoy — so you already knew I knew it when you asked the question. I know it by standing here beside the Hao." (17, tr. Watson 1968:188-9, romanization changed to pinyin)

The traditional interpretation of this "Daoist staple", writes Chad

Hansen (2003:145), is a "humorous miscommunication between a mystic and a

logician". The encounter also outlines part of the Daoist practice of

observing and learning from the natural world.

Another well known part of the book, which is also found in Chapter 2, is usually called "Zhuangzi dreamed he was a butterfly" (莊周夢蝶 Zhuāng Zhōu mèng dié). Again, the names have been changed to pinyin romanization for consistency:

Once Zhuangzi dreamt he was a butterfly, a butterfly flitting and fluttering around, happy with himself and doing as he pleased. He didn't know he was Zhuangzi. Suddenly he woke up and there he was, solid and unmistakable Zhuangzi. But he didn't know if he was Zhuangzi who had dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he was Zhuangzi. Between Zhuangzi and a butterfly there must be some distinction! This is called the Transformation of Things. (2, tr. Burton Watson 1968:49)

This hints at many questions in the philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, and epistemology. The name of the passage has become a common Chinese idiom, and has spread into Western languages as well. It appears, inter alia, as an illustration in Jorge Luis Borges' famous essay "A New Refutation of Time", and may have inspired H.P. Lovecraft's 1918 short story "Polaris". It also appears in Victor Pelevin's 1996 philosophical novel Buddha's Little Finger.

Zhuangzi's philosophy was very influential in the development of Chinese Buddhism, especially Chán (known in Japan as Zen).

Zhuangzi said the world "does not need governing; in fact it should not be governed," and, "Good order results spontaneously when things are let alone." Murray Rothbard called him "perhaps the world's first anarchist".

In Chapter 18, Zhuangzi also mentions life forms have an innate ability or power (hua 化) to transform and adapt to their surroundings. Since his writings give no scientific evidence nor mechanism of biological evolution, while those of Alfred Wallace and Charles Darwin do, his idea about the transformation of life from simple to more complex forms can not be seen as being along the same line of thought. Zhuangzi further mentioned that humans are also subject to this process as humans are a part of nature.