<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Diogenes of Sinope (Διογένης ο Σινωπεύς), 412 B.C.

- Philosopher Zeno of Citium (Ζήνων ο Κιτιεύς), 334 B.C.

PAGE SPONSOR

Diogenes the Cynic (Greek: Διογένης ὁ Κυνικός, Diogenēs ho Kunikos) was a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynic philosophy. Also known as Diogenes of Sinope (Greek: Διογένης ὁ Σινωπεύς, Diogenēs ho Sinōpeus), he was born in Sinope (modern day Sinop, Turkey), an Ionian colony on the Black Sea, in 412 or 404 BCE and died at Corinth in 323 BCE.

Diogenes of Sinope was a controversial figure. His father minted coins for a living and when Diogenes took to "defacement of the currency", he was banished from the city. After being exiled, he moved to Athens to debunk cultural conventions. Diogenes modeled himself on the example of Hercules. He believed that virtue was better revealed in action than in theory. He used his lifestyle and behavior to criticize the social values and institutions of what he saw as a corrupt society. He declared himself a cosmopolitan. There are many tales about him dogging Antisthenes' footsteps and becoming his faithful hound, but it is by no means certain that the two men ever met. Diogenes made a virtue of poverty. He begged for a living and slept in a tub in the marketplace. He became notorious for his philosophical stunts such as carrying a lamp in the daytime, claiming to be looking for an honest man. He publicly mocked Alexander and lived. He embarrassed Plato, disputed his interpretation of Socrates and sabotaged his lectures.

After being captured by pirates and sold into slavery, Diogenes eventually settled in Corinth. There he passed his philosophy of Cynicism to Crates, who taught it to Zeno of Citium, who fashioned it into the school of Stoicism, one of the most enduring schools of Greek philosophy. None of Diogenes’ many writings have survived, but details of his life come in the form of anecdotes (chreia), especially from Diogenes Laërtius, in his book Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. All we have is a number of anecdotes concerning his life and sayings attributed to him in a number of scattered classical sources, none of them definitive.

Diogenes was born in the Greek colony of Sinope on the south

coast of the Black Sea, either in 412 BCE or 404 BCE. Nothing is known

about his early life except that his father Hicesias was a banker.

It seems likely that Diogenes was also enrolled into the banking

business aiding his father. At some point (the exact date is unknown)

Hicesias and Diogenes became embroiled in a scandal involving the

adulteration or defacement of the currency, and Diogenes was exiled from the city.

This aspect of the story seems to be corroborated by archaeology: large

numbers of defaced coins (smashed with a large chisel stamp) have been

discovered at Sinope dating from the middle of the 4th century BCE, and

other coins of the time bear the name of Hicesias as the official who

minted them. The reasons for the defacement of the coinage are unclear,

although Sinope was being disputed between pro - Persian and pro - Greek

factions in the 4th century, and there may have been political rather

than financial motives behind the act.

According to one story, Diogenes went to the Oracle at Delphi to ask for its advice and was told that he should "deface the currency”. Following the debacle in Sinope Diogenes decided that the oracle meant that he should deface the political currency rather than actual coins. He traveled to Athens and made it his life's goal to challenge established customs and values. He argued that instead of being troubled about the true nature of evil, people merely rely on customary interpretations. This distinction between nature ("physis") and custom ("nomos") is a favorite theme of ancient Greek philosophy, and one that Plato takes up in The Republic, in the legend of the Ring of Gyges.

Diogenes arrived in Athens with a slave named Manes who abandoned him

shortly thereafter. With characteristic humor, Diogenes dismissed his

ill fortune by saying, "If Manes can live without Diogenes, why not

Diogenes without Manes?" Diogenes would mock such a relation of extreme dependency. He found the

figure of a master who could do nothing for himself contemptibly

helpless. He was attracted by the ascetic teaching of Antisthenes, a student of Socrates, who (according to Plato) had been present at his death. When Diogenes asked Antisthenes to mentor him, Antisthenes ignored him and reportedly "eventually beat him off with his staff".

Diogenes responds, "Strike, for you will find no wood hard enough to

keep me away from you, so long as I think you've something to say." Diogenes became Antisthenes' pupil, despite the brutality with which he was initially received. Whether the two ever really met is still uncertain,

but he surpassed his master both in reputation and in the austerity of

his life. He considered his avoidance of earthly pleasures a contrast to

and commentary on contemporary Athenian behaviors. This attitude was

grounded in a disdain for what he regarded as the folly, pretense, vanity, self - deception and artificiality of human conduct.

The stories told of Diogenes illustrate the logical consistency of his character. He inured himself to the weather by living in a tub belonging to the temple of Cybele. He destroyed the single wooden bowl he possessed on seeing a peasant boy drink from the hollow of his hands. It was contrary to Athenian customs to eat within the marketplace, and still he would eat, for, as he explained when rebuked, it was during the time he was in the marketplace that he felt hungry. He used to stroll about in full daylight with a lamp; when asked what he was doing, he would answer, "I am just looking for an honest man." Diogenes looked for a human being but reputedly found nothing but rascals and scoundrels.

When Plato gave Socrates' definition of man as "featherless bipeds" and was much praised for the definition, Diogenes plucked a chicken and brought it into Plato's Academy, saying, "Behold! I've brought you a man." After this incident, "with broad flat nails" was added to Plato's definition.

According to a story which seems to have originated with Menippus of Gadara, Diogenes was captured by pirates while on voyage to Aegina and sold as a slave in Crete to a Corinthian named Xeniades. Being asked his trade, he replied that he knew no trade but that of governing men, and that he wished to be sold to a man who needed a master. As tutor to Xeniades' two sons, it is said that he lived in Corinth for the rest of his life, which he devoted to preaching the doctrines of virtuous self - control. There are many stories about what actually happened to him after his time with Xeniades' two sons. There are stories stating he was set free after he became "a cherished member of the household", while one says he was set free almost immediately, and still another states that "he grew old and died at Xeniades’ house in Corinth." He is even said to have lectured to large audiences at the Isthmian Games.

Although most of the stories about him living in a tub are located in Athens, there are some accounts of him living in a tub near the Craneum gymnasium in Corinth:

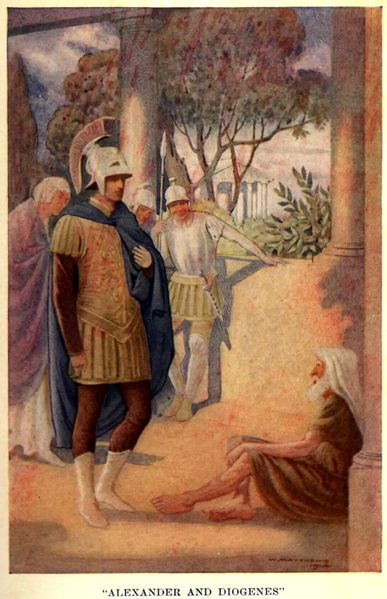

It was in Corinth that a meeting between Alexander the Great and Diogenes is supposed to have taken place. The accounts of Plutarch and Diogenes Laërtius recount that they exchanged only a few words: while Diogenes was relaxing in the sunlight in the morning, Alexander, thrilled to meet the famous philosopher, asked if there was any favor he might do for him. Diogenes replied, "Yes, stand out of my sunlight". Alexander then declared, "If I were not Alexander, then I should wish to be Diogenes." In another account of the conversation, Alexander found the philosopher looking attentively at a pile of human bones. Diogenes explained, "I am searching for the bones of your father but cannot distinguish them from those of a slave."A report that Philip was marching on the town had thrown all Corinth into a bustle; one was furbishing his arms, another wheeling stones, a third patching the wall, a fourth strengthening a battlement, every one making himself useful somehow or other. Diogenes having nothing to do – of course no one thought of giving him a job – was moved by the sight to gather up his philosopher's cloak and begin rolling his tub energetically up and down the Craneum; an acquaintance asked for, and got, the explanation: "I do not want to be thought the only idler in such a busy multitude; I am rolling my tub to be like the rest."

There are conflicting accounts of Diogenes' death. He is alleged variously to have held his breath; to have become ill from eating raw octopus; or to have suffered an infected dog bite. When asked how he wished to be buried, he left instructions to be thrown outside the city wall so wild animals could feast on his body. When asked if he minded this, he said, "Not at all, as long as you provide me with a stick to chase the creatures away!" When asked how he could use the stick since he would lack awareness, he replied "If I lack awareness, then why should I care what happens to me when I am dead?" At the end, Diogenes made fun of people's excessive concern with the "proper" treatment of the dead. The Corinthians erected to his memory a pillar on which rested a dog of Parian marble.

Along with Antisthenes and Crates of Thebes, Diogenes is considered one of the founders of Cynicism. The ideas of Diogenes, like those of most other Cynics, must be arrived at indirectly. No writings of Diogenes survived even though he is reported to have authored over ten books, a volume of letters and seven tragedies. Cynic ideas are inseparable from Cynic practice; therefore what we know about Diogenes is contained in anecdotes concerning his life and sayings attributed to him in a number of scattered classical sources.

Diogenes maintained that all the artificial growths of society were incompatible with happiness and that morality implies a return to the simplicity of nature. So great was his austerity and simplicity that the Stoics would later claim him to be a wise man or "sophos". In his words, "Humans have complicated every simple gift of the gods." Although Socrates had previously identified himself as belonging to the world, rather than a city, Diogenes is credited with the first known use of the word "cosmopolitan". When he was asked where he came from, he replied, "I am a citizen of the world (cosmopolites)". This was a radical claim in a world where a man's identity was intimately tied to his citizenship in a particular city state. An exile and an outcast, a man with no social identity, Diogenes made a mark on his contemporaries.

Diogenes had nothing but disdain for Plato and his abstract philosophy. Diogenes viewed Antisthenes as the true heir to Socrates, and shared his love of virtue and indifference to wealth, together with a disdain for general opinion.

Diogenes shared Socrates' belief that he could function as doctor to

men's souls and improve them morally, while at the same time holding

contempt for their obtuseness. Plato once described Diogenes as "a

Socrates gone mad."

Diogenes taught by living example. He tried to demonstrate that wisdom and happiness belong to the man who is independent of society and that civilization is regressive. He scorned not only family and political social organization, but also property rights and reputation. He even rejected normal ideas about human decency. Diogenes is said to have eaten in the marketplace, urinated on some people who insulted him, defecated in the theater, masturbated in public, and pointed at people with his middle finger.

From "Life of Diogenes": "Someone took him [Diogenes] into a magnificent house and warned him not to spit, whereupon, having cleared his throat, he spat into the man's face, being unable, he said, to find a meaner receptacle."

Many anecdotes of Diogenes refer to his dog like behavior, and his

praise of a dog's virtues. It is not known whether Diogenes was insulted

with the epithet "doggish" and made a virtue of it, or whether he first

took up the dog theme himself. Diogenes believed human beings live

artificially and hypocritically and would do well to study the dog.

Besides performing natural bodily functions in public with ease, a dog

will eat anything, and make no fuss about where to sleep. Dogs live in

the present without anxiety, and have no use for the pretensions of

abstract philosophy. In addition to these virtues, dogs are thought to

know instinctively who is friend and who is foe. Unlike human beings who

either dupe others or are duped, dogs will give an honest bark at the

truth. Diogenes stated that "other dogs bite their enemies, I bite my

friends to save them."

The term "Cynic" itself derives from the Greek word κυνικός, kynikos, "dog - like" and that from κύων, kyôn, "dog" (genitive: kynos). One explanation offered in ancient times for why the Cynics were called dogs was because Antisthenes taught in the Cynosarges gymnasium at Athens. The word Cynosarges means the place of the white dog. Later Cynics also sought to turn the word to their advantage, as a later commentator explained:

There are four reasons why the Cynics are so named. First because of the indifference of their way of life, for they make a cult of indifference and, like dogs, eat and make love in public, go barefoot, and sleep in tubs and at crossroads. The second reason is that the dog is a shameless animal, and they make a cult of shamelessness, not as being beneath modesty, but as superior to it. The third reason is that the dog is a good guard, and they guard the tenets of their philosophy. The fourth reason is that the dog is a discriminating animal which can distinguish between its friends and enemies. So do they recognize as friends those who are suited to philosophy, and receive them kindly, while those unfitted they drive away, like dogs, by barking at them.

As noted, Diogenes' association with dogs was

memorialized by the Corinthians, who erected to his memory a pillar on

which rested a dog of Parian marble.

Diogenes is discussed in a 1983 book by German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk (English language publication in 1987). In his Critique of Cynical Reason, Diogenes is used as an example of Sloterdijk’s idea of the “kynical” — in which personal degradation is used for purposes of community comment or censure. Calling the practice of this tactic “kynismos,” Sloterdijk explains that the kynical actor actually embodies the message he/she is trying to convey. The goal here is typically a false regression that mocks authority — especially authority that the kynical actor considers corrupt, suspect or unworthy.

There is another discussion of Diogenes and the Cynics in Michel Foucault's book Fearless Speech. Here Foucault discusses Diogenes' antics in relation to the speaking of truth (parrhesia) in the ancient world. Foucault expands this reading in his last course at the Collège de France, The Courage of Truth.

In this course Foucault tries to establish a alternative conception of

militancy and revolution through a reading of Diogenes and Cynicism.

Diogenes' name has been applied to a behavioral disorder characterized by involuntary self - neglect and hoarding. The disorder afflicts the elderly and has no relation to Diogenes' deliberate Herculean rejection of material comfort.

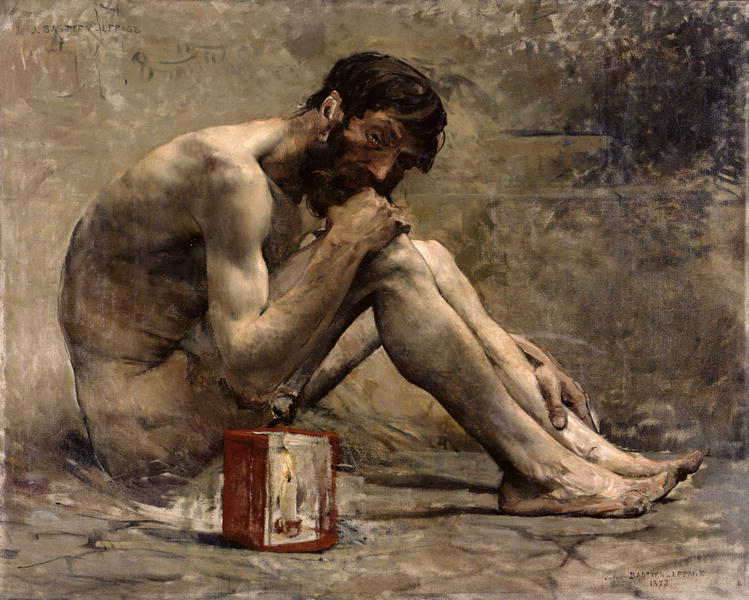

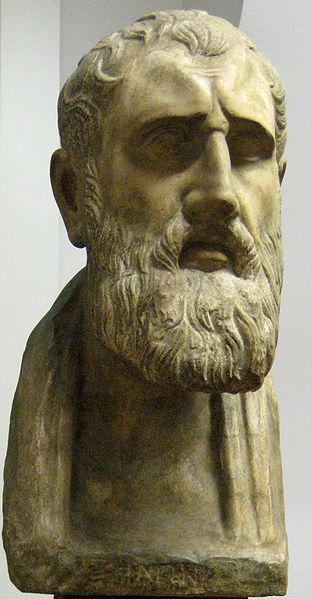

Both in ancient and in modern times, Diogenes' personality has appealed strongly to sculptors and to painters. Ancient busts exist in the museums of the Vatican, the Louvre, and the Capitol. The interview between Diogenes and Alexander is represented in an ancient marble bas relief found in the Villa Albani.

Among artists who have painted the famous encounter of Diogenes with Alexander there are works by de Crayer, de Vos, Assereto, Langetti, Sevin, Sebastiano Ricci, Gandolfi, Wink, Abildgaard, Monsiau, Martin, and Daumier. The famous story of Diogenes searching for an "honest man" has been depicted by Jordaens, van Everdingen, van der Werff, Pannini, and Corinth. Others who have painted him with his famous lantern include de Ribera, Castiglione, Petrini, Gérôme, Bastien - Lepage and Waterhouse. The scene in which Diogenes discards his cup has been painted by Poussin, Rosa, and Martin; and the story of Diogenes begging from a statue has been depicted by Restout. In Raphael's fresco The School of Athens, a lone reclining figure in the foreground represents Diogenes.

Diogenes has also been the subject of sculptures, with famous bas relief images by Puget and Pajou.

Diogenes is referred to in Anton Chekhov's story "Ward No. 6"; William Blake's The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; François Rabelais' Gargantua and Pantagruel; Goethe's poem Genialisch Treiben; as well as in the first sentence of Søren Kierkegaard's novelistic treatise Repetition. In Cervantes' short story "The Man of Glass" ("El licenciado Vidriera"), part of the Novelas Ejemplares collection, the (anti-) hero unaccountably begins to channel Diogenes in a string of tart chreiai once he becomes convinced that he is made of glass. Diogenes gives his own life and opinions in Christoph Martin Wieland's novel Socrates Mainomenos (1770; English translation Socrates Out of His Senses, 1771). Diogenes is the primary model for the philosopher Didactylos in Terry Pratchett's Small Gods. He is mimicked by a beggar - spy in Jacqueline Carey's Kushiel's Scion and paid tribute to with a costume in a party by the main character in its sequel, Kushiel's Justice. The character Lucy Snowe in Charlotte Bronte's novel Villette is given the nickname Diogenes. Diogenes also features in Part Four of Elizabeth Smart's By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept. He is a figure in Seamus Heaney's The Haw Lantern. In Christopher Moore's Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal, one of Jesus' apostles is a devotee of Diogenes, complete with his own pack of dogs which he refers to as his own disciples. His story opens the first chapter of Dolly Freed's 1978 book Possum Living. The dog that Paul Dombey befriends in Charles Dickens' Dombey and Son is called Diogenes. Alexander's meeting with Diogenes is portrayed in Valerio Manfredi's Alexander: The Ends of the Earth.

The many allusions to dogs in Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens are references to the school of Cynicism that could be interpreted as suggesting a parallel between the misanthropic hermit, Timon, and Diogenes; but Shakespeare would have had access to Michel de Montaigne’s essay, "Of Democritus and Heraclitus", which emphasized their differences: Timon actively wishes men ill and shuns them as dangerous, whereas Diogenes esteems them so little that contact with them could not disturb him. "Timonism" is in fact often contrasted with "Cynicism": "Cynics saw what people could be and were angered by what they had become; Timonists felt humans were hopelessly stupid & uncaring by nature and so saw no hope for change."

The philosopher's name was adopted by the fictional Diogenes Club, an organization that Sherlock Holmes' brother Mycroft Holmes belongs to in the story "The Greek Interpreter" by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

It is called such as its members are educated, yet untalkative and have

a dislike of socializing, much like the philosopher himself. The group

is the focus of a number of Holmes pastiches by Kim Newman.

Zeno of Citium (Greek: Ζήνων ὁ Κιτιεύς, Zēnōn ho Kitiéŭs;, c. 334 BC – c. 262 BC) was a Greek language philosopher of Phoenician origin from Citium (Greek: Κίτιον). Zeno was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 BC. Based on the moral ideas of the Cynics, Stoicism laid great emphasis on goodness and peace of mind gained from living a life of virtue in accordance with nature. It proved very successful, and flourished as the dominant philosophy from the Hellenistic period through to the Roman era.

Zeno was born c. 334 BC, in Citium in Cyprus. Most of the details known about his life come from the anecdotes preserved by Diogenes Laërtius in his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. Diogenes relates a legend that Zeno was a merchant and that after surviving a shipwreck, Zeno wandered into a bookshop in Athens and was attracted to some writings about Socrates. He asked the librarian how to find such a man. In response, the librarian pointed to Crates of Thebes, the most famous Cynic living at that time in Greece.

Zeno is described as a haggard, tanned person, living a spare, ascetic life. This coincides with the influences of Cynic teaching, and was, at least in part, continued in his Stoic philosophy. In one incident during his tutelage with Crates, he was made to carry a pot of lentil soup around the city. After Zeno began carrying the pot, Crates smashed it with his staff, splattering the lentil soup all over his surprised student. When Zeno began to run off in embarrassment, Crates chided, "Why run away, my little Phoenician? Nothing terrible has befallen you!"

Apart from Crates, Zeno studied under the philosophers of the Megarian school, including Stilpo, and the dialecticians Diodorus Cronus, and Philo. He is also said to have studied Platonist philosophy under the direction of Xenocrates, and Polemo.

Zeno began teaching in the colonnade in the Agora of Athens known as the Stoa Poikile in 301 BC. His disciples were initially called Zenonians, but eventually they came to be known as Stoics, a name previously applied to poets who congregated in the Stoa Poikile.

Among the admirers of Zeno was king Antigonus II Gonatas of Macedonia, who, whenever he came to Athens, would visit Zeno. Zeno is said to have declined an invitation to visit Antigonus in Macedonia, although their supposed correspondence preserved by Laërtius is undoubtably the invention of a later rhetorician. Zeno instead sent his friend and disciple Persaeus, who had lived with Zeno in his house. Among Zeno's other pupils there were Aristo of Chios, Sphaerus, and Cleanthes who succeeded Zeno as the head (scholarch) of the Stoic school in Athens.

Zeno is said to have declined Athenian citizenship when it was offered to him, fearing that he would appear unfaithful to his native land Phoenicia, where he was highly esteemed. We are also told that Zeno was of an earnest, if not gloomy disposition; that he preferred the company of the few to the many; that he was fond of burying himself in investigations; and that he had a dislike to verbose and elaborate speeches. Diogenes Laërtius has preserved many clever and witty remarks by Zeno, the veracity of which cannot be ascertained.

Zeno died around 262 BC. Laërtius reports about his death:

- As he was leaving the school he tripped and fell, breaking his toe.

Striking the ground with his fist, he quoted the line from the Niobe:

- "I come, I come, why dost thou call for me?"

- and died on the spot through holding his breath.

During his lifetime, Zeno received appreciation for his philosophical and pedagogical teachings. Amongst other things, Zeno was honored with the golden crown, and a tomb was built in honor of his moral influence on the youth of his era.

The crater Zeno on the Moon is named in his honor.

Following the ideas of the Academics, Zeno divided philosophy into three parts: Logic (a very wide subject including rhetoric, grammar, and the theories of perception and thought); Physics (not just science, but the divine nature of the universe as well); and Ethics,

the end goal of which was to achieve happiness through the right way of

living according to Nature. Because Zeno's ideas were built upon by Chrysippus

and other Stoics, it can be difficult to determine, in some areas,

precisely what he thought, but his general views can be outlined:

In his treatment of Logic, Zeno was influenced by Stilpo and the other Megarians. Zeno urged the need to lay down a basis for Logic because the wise person must know how to avoid deception. Cicero accused Zeno of being inferior to his philosophical predecessors in his treatment of Logic, and it seems true that a more exact treatment of the subject was laid down by his successors, including Chrysippus. Zeno divided true conceptions into the comprehensible and the incomprehensible, permitting for free will the power of assent (sunkatathesis) in distinguishing between sense impressions. Zeno said that there were four stages in the process leading to true knowledge, which he illustrated with the example of the flat, extended hand, and the gradual closing of the fist:

Zeno stretched out his fingers, and showed the palm of his hand, - "Perception," - he said, - "is a thing like this." - Then, when he had closed his fingers a little, - "Assent is like this." - Afterwards, when he had completely closed his hand, and showed his fist, that, he said, was Comprehension. From which simile he also gave that state a new name, calling it katalepsis. But when he brought his left hand against his right, and with it took a firm and tight hold of his fist: - "Knowledge" - he said, was of that character; and that was what none but a wise person possessed.

The Universe, in Zeno's view, is God: a divine reasoning entity, where all the parts belong to the whole. Into this pantheistic system he incorporated the physics of Heraclitus; the Universe contains a divine artisan - fire, which foresees everything, and extending throughout the Universe, must produce everything:

Zeno, then, defines nature by saying that it is artistically working fire, which advances by fixed methods to creation. For he maintains that it is the main function of art to create and produce, and that what the hand accomplishes in the productions of the arts we employ, is accomplished much more artistically by nature, that is, as I said, by artistically working fire, which is the master of the other arts.

This divine fire, or aether, is the basis for all activity in the Universe, operating on otherwise passive matter, which neither increases nor diminishes itself. The primary substance in the Universe comes from fire, passes through the stage of air, and then becomes water: the thicker portion becoming earth, and the thinner portion becoming air again, and then rarefying back into fire. Individual souls are part of the same fire as the world - soul of the Universe. Following Heraclitus, Zeno adopted the view that the Universe underwent regular cycles of formation and destruction.

The Nature of the Universe is such that it accomplishes what is right and prevents the opposite, and is identified with unconditional Fate, while allowing it the free - will attributed to it.

Like the Cynics, Zeno recognized a single, sole and simple good, which is the only goal to strive for. "Happiness is a good flow of life," said Zeno, and this can only be achieved through the use of right Reason coinciding with the Universal Reason (Logos), which governs everything. A bad feeling (pathos) "is a disturbance of the mind repugnant to Reason, and against Nature." This consistency of soul, out of which morally good actions spring, is Virtue, true good can only consist in Virtue.

Zeno deviated from the Cynics in saying that things that are morally indifferent could nevertheless have value. Things have a relative value in proportion to how they aid the natural instinct for self - preservation. That which is to be preferred is a "fitting action" (kathêkon), a designation Zeno first introduced. Self - preservation, and the things that contribute towards it, has only a conditional value; it does not aid happiness, which depends only on moral actions.

Just as Virtue can only exist within the dominion of Reason, so Vice can only exist with the rejection of Reason. Virtue is absolutely opposed to Vice, the two cannot exist in the same thing together, and cannot be increased or decreased; no one moral action is more virtuous than another. All actions are either good or bad, since impulses and desires rest upon free consent, and hence even passive mental states or emotions that are not guided by reason are immoral, and produce immoral actions. Zeno distinguished four negative emotions: desire, fear, pleasure and pain (epithumia, phobos, hêdonê, lupê), and he was probably responsible for distinguishing the three corresponding positive emotions: will, caution, and joy (boulêsis, eulabeia, chara), with no corresponding rational equivalent for pain. All errors must be rooted out, not merely set aside, and replaced with right Reason.

None of Zeno's writings have survived except as fragmentary quotations preserved by later writers. The titles of many of Zeno's writings are known; they are known to have been these:

- Ethical writings:

- Πολιτεία - Republic

- ἠθικά - Ethics

- περὶ τοῦ κατὰ φύσιν βίου - On Life according to Nature

- περὶ ὁρμῆς ἧ περὶ ἁνθρώπου φύσεως - On Impulse, or on the Nature of Humans

- περὶ παθῶν - On Passions

- περὶ τοῦ καθήκοντος - On Duty

- περὶ νόμου - On Law

- περὶ Έλληνικῆς παιδείας - On Greek Education

- ἐρωτικὴ τέχνη - The Art of Love

- Physical writings:

- περὶ τοῦ ὅλου - On the Universe

- περὶ οὐσίας - On Being

- περὶ σημείων - On Signs

- περὶ ὄψεως - On Sight

- περὶ τοῦ λόγου - On the Logos

- Logical writings:

- διατριϐαί - Discourses

- περὶ λεξεως - On Verbal Style

- λύσεις, ἔλεγχοι - Solutions and Refutations

- Other works:

- περὶ ποιητικῆς ἀκροάσεως - On Poetical Readings

- προϐλημάτων Όμηρικῶν πέντε - Homeric Problems

- καθολικά - General Things

- Άπομνημονεύματα Κράτητος - Reminiscences of Crates

- Πυθαγορικά - Pythagorean Doctrines

The most famous of these works was Zeno's Republic, a work written in conscious imitation of (or opposition to) Plato. Although it has not survived, more is known about it than any of his other works. It outlined Zeno's vision of the ideal Stoic society built on egalitarian principles.