<Back to Index>

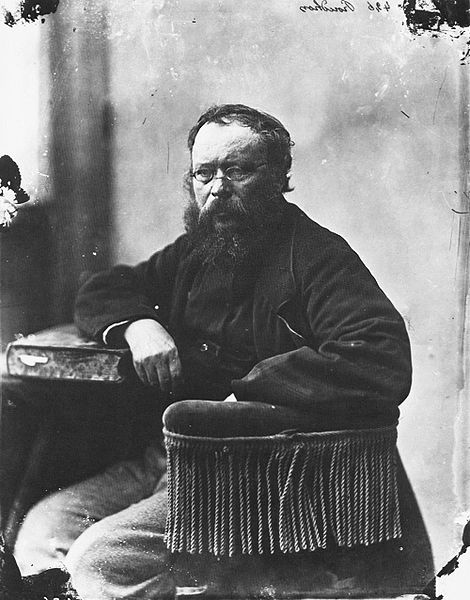

- Politician and Philosopher Pierre - Joseph Proudhon, 1809

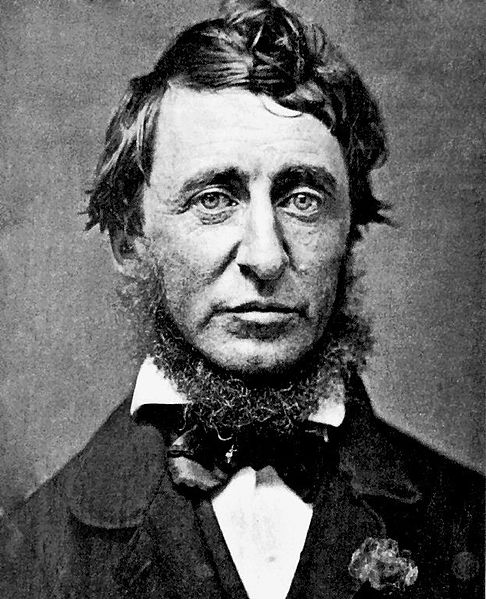

- Writer and Philosopher Henry David Thoreau, 1817

PAGE SPONSOR

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (15 January 1809 – 19 January 1865) was a French politician, mutualist philosopher and socialist. He was a member of the French Parliament, and he was the first person to call himself an "anarchist". He is considered among the most influential theorists and organizers of anarchism. After the events of 1848 he began to call himself a federalist.

Proudhon, who was born in Besançon, was a printer who taught himself Latin in order to better print books in the language. His best known assertion is that Property is Theft!, contained in his first major work, What is Property? Or, an Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government (Qu'est-ce que la propriété? Recherche sur le principe du droit et du gouvernement), published in 1840. The book's publication attracted the attention of the French authorities. It also attracted the scrutiny of Karl Marx, who started a correspondence with its author. The two influenced each other: they met in Paris while Marx was exiled there. Their friendship finally ended when Marx responded to Proudhon's The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty with the provocatively titled The Poverty of Philosophy. The dispute became one of the sources of the split between the anarchist and Marxist wings of the International Working Men's Association. Some, such as Edmund Wilson, have contended that Marx's attack on Proudhon had its origin in the latter's defense of Karl Grün, whom Marx bitterly disliked but who had been preparing translations of Proudhon's work.

Proudhon favored workers' associations or co-operatives, as well as individual worker / peasant possession, over private ownership or the nationalization of land and workplaces. He considered that social revolution could be achieved in a peaceful manner. In The Confessions of a Revolutionary Proudhon asserted that, Anarchy is Order Without Power, the phrase which much later inspired, in the view of some, the anarchist circled-A symbol, today "one of the most common graffiti on the urban landscape." He unsuccessfully tried to create a national bank, to be funded by what became an abortive attempt at an income tax on capitalists and stockholders. Similar in some respects to a credit union, it would have given interest - free loans.

Proudhon was born in Besançon, France; his father was a brewer's cooper.

As a boy, he herded cows and followed other similar, simple pursuits.

But he was not entirely self - educated; at age 16, he entered his town's

college, though his family was so poor that he could not buy the

necessary books. He had to borrow them from his fellow students in order

to copy the lessons. At age 19, he became a working compositor; later

he rose to be a corrector for the press, proofreading ecclesiastical works, and thereby acquiring a very competent knowledge of theology. In this way also he came to learn Hebrew, and to compare it with Greek, Latin and French; and it was the first proof of his intellectual audacity that on the strength of this he wrote an Essai de grammaire génerale. In 1838, he obtained the pension Suard, a bursary of 1500 francs a year for three years, for the encouragement of young men of promise, which was in the gift of the Academy of Besançon.

In 1830, he wrote a treatise L'Utilité de la célébration du dimanche, which contained the seeds of his revolutionary ideas. About this time he went to Paris, France, where he lived a poor, ascetic and studious life, but became acquainted with the socialist ideas which were then fomenting in the capital. In 1840 he published his first work Qu'est-ce que la propriété (or "What Is Property"). His famous answer to this question, "La propriété, c'est le vol" ("property is theft"), naturally did not please the Academy of Besançon, and there was some talk of withdrawing his pension; but he held it for the regular period.

His third memoir on property was a letter to the Fourierist, M. Considérant; he was tried for it at Besançon but was acquitted. In 1846, he published the Système des contradictions économiques ou Philosophie de la misère (or "The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty").

For some time, Proudhon ran a small printing establishment at

Besançon, but without success; afterwards he became connected as a

kind of

manager with a commercial firm in Lyon,

France. In 1847, he left this job and finally settled in Paris, where

he was now becoming celebrated as a leader of innovation. In this year

he also became a Freemason.

Proudhon was surprised by the Revolutions of 1848 in France. He participated in the February uprising and the composition of what he termed "the first republican proclamation" of the new republic. But he had misgivings about the new provisional government, headed by Dupont de l'Eure (1767 – 1855), who, since the French Revolution in 1789, had been a longstanding politician, although often in the opposition. Beside Dupont de l'Eure, the provisional government was dominated by liberals such as Lamartine (Foreign Affairs), Ledru -Rollin (Interior), Crémieux (Justice), Burdeau (War), etc., because it was pursuing political reform at the expense of the socio - economic reform, which Proudhon considered basic. As during the 1830 July Revolution, the Republican - Socialist Party had set up a counter - government in the Hotel de Ville, including Louis Blanc, Armand Marrast, Ferdinand Flocon, and workman Albert.

Proudhon published his own perspective for reform which was completed in 1849, Solution du problème social ("Solution of the Social Problem"), in which he laid out a program of mutual financial cooperation among workers. He believed this would transfer control of economic relations from capitalists and financiers to workers. The central part of his plan was the establishment of a bank to provide credit at a very low rate of interest and the issuing exchange notes that would circulate instead of money based on gold.

During the Second French Republic (1848 – 1852), Proudhon had his biggest public effect through journalism. He got involved with four newspapers: Le Représentant du Peuple (February 1848 – August 1848); Le Peuple (September 1848 – June 1849); La Voix du Peuple (September 1849 – May 1850); Le Peuple de 1850 (June 1850 – October 1850). His polemical writing style, combined with his perception of himself as a political outsider, produced a cynical, combative journalism that appealed to many French workers but alienated others. He repeatedly criticized the government's policies and promoted reformation of credit and exchange. He tried to establish a popular bank (Banque du peuple) early in 1849, but despite over 13,000 people signing up (mostly workers), receipts were limited falling short of 18,000FF and the whole enterprise was essentially stillborn.

Proudhon ran for the constituent assembly in April 1848, but was not elected, although his name appeared on the ballots in Paris, Lyon, Besançon and Lille, France. He was successful, in the complementary elections of June 4, and served as a deputy during the debates over the National Workshops, created by the February 25, 1848, decree passed by Republican Louis Blanc. The workshops were to give work to the unemployed. Proudhon was never enthusiastic about such workshops, perceiving them to be essentially charitable institutions that did not resolve the problems of the economic system. He was against their elimination unless an alternative could be found for the workers who relied on the workshops for subsistence.

In 1848 the closing of the National Workshops provoked the June Days Uprising and the violence shocked Proudhon. Visiting the barricades personally, he later reflected that his presence at the Bastille at this time was "one of the most honorable acts of my life". But in general during the tumultuous events of 1848, Proudhon opposed insurrection by preaching peaceful conciliation, a stance that was in accord with his lifelong stance against violence. He disapproved of the revolts and demonstrations of February, May, and June 1848, though sympathetic to the social and psychological injustices that the insurrectionists had been forced to endure.

Proudhon died in Passy, and is buried in Paris, at the cemetery of Montparnasse (2nd division, near the Lenoir alley, in the tomb of the Proudhon family).

Proudhon declared in 1849:

| “ | Whoever lays his hand on me to govern me is a usurper and tyrant, and I declare him my enemy. | ” |

He was the first person to refer to himself as an anarchist. In What is Property, published in 1840, he defined anarchy as "the absence of a master, of a sovereign", and in The General idea of the Revolution (1851) he urged a "society without authority." He extended this analysis beyond political institutions, arguing in What is Property? that "proprietor" was "synonymous" with "sovereign". For Proudhon:

| “ | "Capital"... in the political field is analogous to "government"... The economic idea of capitalism, the politics of government or of authority, and the theological idea of the Church are three identical ideas, linked in various ways. To attack one of them is equivalent to attacking all of them . . . What capital does to labor, and the State to liberty, the Church does to the spirit. This trinity of absolutism is as baneful in practice as it is in philosophy. The most effective means for oppressing the people would be simultaneously to enslave its body, its will and its reason. | ” |

Proudhon in his earliest works analyzed the nature and problems of the capitalist economy. While deeply critical of capitalism, he also objected to those contemporary socialists who advocated centralized, hierarchical forms of association or state control of the economy. In a sequence of commentaries, from What is Property? (1840) through the posthumously published Théorie de la propriété (Theory of Property, 1863 – 64), he declared in turn that "property is theft", "property is impossible", "property is despotism" and "property is freedom". When he said "property is theft", he was referring to the landowner or capitalist who he believed "stole" the profits from laborers. For Proudhon, the capitalist's employee was "subordinated, exploited: his permanent condition is one of obedience".

In asserting that property is freedom, he was referring not only to the product of an individual's labor, but to the peasant or artisan's home and tools of his trade and the income he received by selling his goods. For Proudhon, the only legitimate source of property is labor. What one produces is one's property and anything beyond that is not. He advocated worker self - management and was opposed to the private ownership of the means of production. As he put it in 1848:

| “ | "Under the law of association, transmission of wealth does not apply to the instruments of labor, so cannot become a cause of inequality... We are socialists... under universal association, ownership of the land and of the instruments of labor is social ownership... We want the mines, canals, railways handed over to democratically organized workers' associations... We want these associations to be models for agriculture, industry and trade, the pioneering core of that vast federation of companies and societies, joined together in the common bond of the democratic and social Republic." | ” |

Proudhon called himself a socialist, but he opposed state ownership of capital goods in favor of ownership by workers themselves in associations. This makes him one of the first theorists of libertarian socialism. Proudhon was one of the main influences on the theory of workers' self - management (autogestion), in the late 19th and 20th century.

Proudhon strenuously rejected the ownership of the products of labor by society or the state, arguing in What is Property? that while "property in product [...] does not carry with it property in the means of production"

[...] The right to product is exclusive [...] the right to means is

common" and applied this to the land ("the land is [...] a common thing") and workplaces ("all accumulated capital being social property, no one can be its exclusive proprietor".)

He argued that while society owned the means of production or land,

users would control and run them (under supervision from society), with

the "organizing of regulating societies" in order to "regulate the

market".

This use - ownership he called "possession", and this economic system mutualism. Proudhon had many arguments against entitlement to land and capital, including reasons based on morality, economics, politics and individual liberty. One such argument was that it enabled profit, which in turn led to social instability and war by creating cycles of debt that eventually overcame the capacity of labor to pay them off. Another was that it produced "despotism" and turned workers into wage workers subject to the authority of a boss.

In What Is Property? Proudhon wrote:

Property, acting by exclusion and encroachment, while population was increasing, has been the life - principle and definitive cause of all revolutions. Religious wars, and wars of conquest, when they have stopped short of the extermination of races, have been only accidental disturbances, soon repaired by the mathematical progression of the life of nations. The downfall and death of societies are due to the power of accumulation possessed by property.

Joseph Déjacque attacked Proudhon's support for notions of patriarchy, what late 20th century anarchists would term sexism, as quite at odds with anarchist principles.

Towards the end of his life, Proudhon modified some of his earlier views. In The Principle of Federation (1863) he modified his earlier anti - state position, arguing for "the balancing of authority by liberty" and put forward a decentralized "theory of federal government". He also defined anarchy differently as "the government of each by himself", which meant "that political functions have been reduced to industrial functions, and that social order arises from nothing but transactions and exchanges." This work also saw him call his economic system an "agro - industrial federation", arguing that it would provide "specific federal arrangements is to protect the citizens of the federated states from capitalist and financial feudalism, both within them and from the outside" and so stop the re-introduction of "wage labor." This was because "political right requires to be buttressed by economic right."

In the posthumously published Theory of Property, he argued that "property is the only power that can act as a counterweight to the State." Hence, "Proudhon could retain the idea of property as theft, and at the same time offer a new definition of it as liberty. There is the constant possibility of abuse, exploitation, which spells theft. At the same time property is a spontaneous creation of society and a bulwark against the ever - encroaching power of the State."

He continued to oppose both capitalist and state property. In Theory of Property

he maintains: "Now in 1840, I categorically rejected the notion of

property... for both the group and the individual", but then states his

new theory of property: "property is the greatest revolutionary force

which exists, with an unequaled capacity for setting itself against

authority..." and the "principal function of private property within the

political system will be to act as a counterweight to the power of the

State, and by so doing to insure the liberty of the individual."

However, he continued to oppose concentrations of wealth and property,

arguing for small - scale property ownership associated with peasants

and

artisans. He still opposed private property in land: "What I cannot

accept, regarding land, is that the work put in gives a right to

ownership of what has been worked on." In addition, he still believed

that that "property" should be more equally distributed and limited in

size to that actually used by individuals, families and workers

associations. He supported the right of inheritance, and defended "as one of the foundations of the family and society."

However, he refused to extend this beyond personal possessions arguing

that "[u]nder the law of association, transmission of wealth does not

apply to the instruments of labor."

As a consequence of his opposition to profit, wage labor, worker exploitation, ownership of land and capital, as well as to state property, Proudhon rejected both capitalism and communism. He adopted the term mutualism for his brand of anarchism, which involved control of the means of production by the workers. In his vision, self - employed artisans, peasants, and cooperatives would trade their products on the market. For Proudhon, factories and other large workplaces would be run by "labor associations" operating on directly democratic principles. The state would be abolished; instead, society would be organized by a federation of "free communes" (a commune is a local municipality in French). In 1863 Proudhon said: "All my economic ideas as developed over twenty - five years can be summed up in the words: agricultural - industrial federation. All my political ideas boil down to a similar formula: political federation or decentralization."

Proudhon opposed the charging of interest and rent, but did not seek to abolish them by law: "I protest that when I criticized... the complex of institutions of which property is the foundation stone, I never meant to forbid or suppress, by sovereign decree, ground rent and interest on capital. I think that all these manifestations of human activity should remain free and voluntary for all: I ask for them no modifications, restrictions or suppressions, other than those which result naturally and of necessity from the universalization of the principle of reciprocity which I propose."

Proudhon was a revolutionary, but his revolution did not mean violent upheaval or civil war, but rather the transformation of society. This transformation was essentially moral in nature and demanded the highest ethics from those who sought change. It was monetary reform, combined with organizing a credit bank and workers associations, that Proudhon proposed to use as a lever to bring about the organization of society along new lines. He did not suggest how the monetary institutions would cope with the problem of inflation and with the need for the efficient allocation of scarce resources.

He made few public criticisms of Marx or Marxism, because in his lifetime Marx was a relatively minor thinker; it was only after Proudhon's death that Marxism became a large movement. He did, however, criticize authoritarian socialists of his period. This included the state socialist Louis Blanc, of whom Proudhon said, "Let me say to M. Blanc: you desire neither Catholicism nor monarchy nor nobility, but you must have a God, a religion, a dictatorship, a censorship, a hierarchy, distinctions and ranks. For my part, I deny your God, your authority, your sovereignty, your judicial State, and all your representative mystifications." It was Proudhon's book What is Property? that convinced the young Karl Marx that private property should be abolished.

In one of his first works, The Holy Family, Marx said, "Not only does Proudhon write in the interest of the proletarians,

he is himself a proletarian, an ouvrier. His work is a scientific

manifesto of the French proletariat." Marx, however, disagreed with

Proudhon's anarchism and later published vicious criticisms of Proudhon.

Marx wrote The Poverty of Philosophy as a refutation of Proudhon's The Philosophy of Poverty.

Although ultimately overshadowed by Karl Marx, who dismissed him as a bourgeois socialist for his pro - market views, Proudhon had an immediate and lasting influence on the anarchist movement, and, more recently, in the aftermaths of May 1968 and after the end of the Cold War. His essay on What Is Government? is quite well known:

To be GOVERNED is to be watched, inspected, spied upon, directed, law - driven, numbered, regulated, enrolled, indoctrinated, preached at, controlled, checked, estimated, valued, censured, commanded, by creatures who have neither the right nor the wisdom nor the virtue to do so. To be GOVERNED is to be at every operation, at every transaction noted, registered, counted, taxed, stamped, measured, numbered, assessed, licensed, authorized, admonished, prevented, forbidden, reformed, corrected, punished. It is, under pretext of public utility, and in the name of the general interest, to be place[d] under contribution, drilled, fleeced, exploited, monopolized, extorted from, squeezed, hoaxed, robbed; then, at the slightest resistance, the first word of complaint, to be repressed, fined, vilified, harassed, hunted down, abused, clubbed, disarmed, bound, choked, imprisoned, judged, condemned, shot, deported, sacrificed, sold, betrayed; and to crown all, mocked, ridiculed, derided, outraged, dishonored. That is government; that is its justice; that is its morality.

—P.-J. Proudhon, "What Is Government?", General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century, translated by John Beverly Robinson (London: Freedom Press, 1923), pp. 293 - 294.

In addition to being considered a founding father of anarchism, he has also been considered by some to be a forerunner of fascism. He was first used as a reference, surprisingly, in the Cercle Proudhon, a right wing association formed in 1911 by George Valois and Edouard Berth. Both had been brought together by the syndicalist Georges Sorel. But they would tend toward a synthesis of socialism and nationalism, mixing Proudhon's mutualism with Charles Maurras' integralist nationalism. In 1925, George Valois founded the Faisceau, the first fascist league which took its name from Mussolini's fasci. Historian of fascism, in particular of French fascists, Zeev Sternhell, has noted this use of Proudhon by the far right. In The Birth Of Fascist Ideology, he states that:

"the Action Française... from its inception regarded the author of La philosophie de la misère as one of its masters. He was given a place of honor in the weekly section of the journal of the movement entitled, precisely, 'Our Masters.' Proudhon owed this place in L'Action française to what the Maurrassians saw as his antirepublicanism, his anti - Semitism, his loathing of Rousseau, his disdain for the French Revolution, democracy, and parliamentarianism: and his championship of the nation, the family, tradition, and the monarchy."

K. Steven Vincent, however, states that “to argue that Proudhon was a proto - fascist suggests that one has never looked seriously at Proudhon’s writings.”

Proudhon influenced the non - conformists of the 1930s, as well as anarchism. In the 1960s, he became the main influence of autogestion (workers' self - management) in France, inspiring the CFDT trade union, created in 1964, and the Unified Socialist Party (PSU), founded in 1960 and led until 1967 by Édouard Depreux. In particular, autogestion influenced the LIP self - management experience in Besançon.

Proudhon's thought has seen some revival since the end of the Cold War and the fall of "real socialism" in the Eastern Bloc. It can be loosely related to modern attempts at direct democracy. The Groupe Proudhon, related to the Fédération Anarchiste (Anarchist Federation), published a review from 1981 to 1983 and again since 1994. (The first period corresponds with the 1981 election of Socialist candidate François Mitterrand and the economic liberal turn of 1983 taken by the Socialist government.) It is staunchly anti - fascist and related to the Section Carrément Anti Le Pen which opposed Jean - Marie Le Pen).

English - speaking anarchists have also attempted to keep the Proudhonian

tradition alive and to engage in dialogue with Proudhon's ideas: Kevin Carson's mutualism is self - consciously Proudhonian, and Shawn P. Wilbur

has continued both to facilitate the translation into English of

Proudhon's texts and to reflect on their significance for the

contemporary anarchist project.

Stewart Edwards, the editor of the Selected Writings Of Pierre - Joseph Proudhon, remarks: "Proudhon's diaries (Carnets, ed. P. Haubtmann, Marcel Rivière, Paris 1960 to date) reveal that he had almost paranoid feelings of hatred against the Jews, common in Europe at the time. In 1847 he considered publishing an article against the Jewish race, which he said he "hated". The proposed article would have "called for the expulsion of the Jews from France... The Jew is the enemy of the human race. This race must be sent back to Asia, or exterminated. H. Heine, A. Weil, and others are simply secret spies. Rothschild, Crémieux, Marx, Fould, evil choleric, envious, bitter men etc., etc., who hate us." (Carnets, vol. 2, p. 337: No VI, 178)

J. Salwyn Schapiro argued in 1945 that Proudhon was a racist, “a glorifier of war for its own sake” and his “advocacy of personal dictatorship and his laudation of militarism can hardly be equaled in the reactionary writings of his or of our day.”

Other scholars have rejected Schapiro's claims. Graham Purchase states that while Proudhon was personally racist, “anti - semitism formed no part of Proudhon’s revolutionary program.” Proudhon himself argued that under mutualism “[t]here will no longer be nationality, no longer fatherland, in the political sense of the words: they will mean only places of birth. Man, of whatever race or color he may be, is an inhabitant of the universe; citizenship is everywhere an acquired right.”

Proudhon also opposed militarism and war, arguing that the “end of militarism is the mission of the nineteenth century, under pain of indefinite decadence” and that the “workers alone are capable of putting an end to war by creating economic equilibrium. This presupposes a radical revolution in ideas and morals.” As Robert L. Hoffman notes that War and Peace “ends by condemning war without reservation” and its “conclusion [is] that war is obsolete.” He argues that it “difficult to see how his purpose and overall conception could have been mistaken by any who read the whole book with care.” Marxist John Ehrenberg summarized Proudhon's position:

“If injustice was the cause of war, it followed that conflict could not be eliminated until society was reorganized along egalitarian lines. Proudhon had wanted to prove that the reign of political economy would be the reign of peace, finding it difficult to believe that people really thought he was defending militarism.”

Proudhon also rejected dictatorship, stating in the 1860s that “what I will always be . . . a republican, a democrat even, and a socialist into the bargain.” Henri de Lubac argued that, in terms of Proudhon’s critique of democracy, “we must not allow all this to hoodwink us. His invectives against democracy were not those of a counter - revolutionary. They were aimed at what he himself called ‘the false democracy’ . . . The attacked an apparently liberal ‘pseudo - democracy’ which ‘was not economic and social’ . . . ‘a Jacobinical democracy’” Proudhon “did not want to destroy, but complete, the work of 1789” and while “he had a grudge against the ‘old democracy’, the democracy of Robespierre and Marat” he repeatedly contrasted it “with a ‘young democracy’, which was a ‘social democracy.’”

According to historian of anarchism George Woodcock, some positions Proudhon took "sorted oddly with his avowed anarchism". Woodcock cited for example Proudhon's proposition that each citizen perform one or two years militia service. The proposal appeared in the Programme Revolutionaire, an electoral manifesto issued by Proudhon after he was asked to run for a position in the provisional government. The text reads: "7° 'L'armée. – Abolition immédiate de la conscription et des remplacements; obligation pour tout citoyen de faire, pendant un ou deux ans, le service militaire ; application de l'armée aux services administratifs et travaux d'utilité publique." ("Military service by all citizens is proposed as an alternative to conscription and the practice of "replacement", by which those who could avoided such service.") However, in the same document, Proudhon described the "form of government" he was proposing as "a centralization analogous with that of the State, but in which no one obeys, no one is dependent, and everyone is free and sovereign."

Albert Meltzer has said that that though Proudhon used the term "anarchist", he was not one, and that he never engaged in "anarchist activity or struggle" but rather in "parliamentary activity".

Iain McKay, author of 'An Anarchist FAQ' (AK Press, 2007) has stated that:

This is not to say that Proudhon was without flaws, for he had many. He was not consistently libertarian in his ideas, tactics and language. His personal bigotries are disgusting and few modern anarchists would tolerate them - Namely, racism and sexism. He made some bad decisions and occasionally ranted in his private notebooks (where the worst of his anti - Semitism was expressed). While he did place his defense of the patriarchal family at the core of his ideas, they are in direct contradiction to his own libertarian and egalitarian ideas. In terms of racism, he sometimes reflected the less - than - enlightened assumptions and prejudices of the nineteenth century. While this does appear in his public work, such outbursts are both rare and asides (usually an extremely infrequent passing anti - Semitic remark or caricature). In short, “racism was never the basis of Proudhon’s political thinking” (Gemie) and “anti-Semitism formed no part of Proudhon’s revolutionary program.” (Robert Graham) To quote Proudhon: “There will no longer be nationality, no longer fatherland, in the political sense of the words: they will mean only places of birth. Man, of whatever race or color he may be, is an inhabitant of the universe; citizenship is everywhere an acquired right.”

—Iain McKay, "Property Is Theft! A Pierre - Joseph Proudhon Anthology, 2011"

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817 – May 6, 1862) was an American author, poet, philosopher, abolitionist, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, historian and leading transcendentalist. He is best known for his book Walden, a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings, and his essay Civil Disobedience, an argument for individual resistance to civil government in moral opposition to an unjust state.

Thoreau's books, articles, essays, journals, and poetry total over 20 volumes. Among his lasting contributions were his writings on natural history and philosophy, where he anticipated the methods and findings of ecology and environmental history, two sources of modern day environmentalism. His literary style interweaves close natural observation, personal experience, pointed rhetoric, symbolic meanings, and historical lore, while displaying a poetic sensibility, philosophical austerity, and "Yankee" love of practical detail. He was also deeply interested in the idea of survival in the face of hostile elements, historical change, and natural decay; at the same time he advocated abandoning waste and illusion in order to discover life's true essential needs.

He was a lifelong abolitionist, delivering lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law while praising the writings of Wendell Phillips and defending abolitionist John Brown. Thoreau's philosophy of civil disobedience later influenced the political thoughts and actions of such notable figures as Leo Tolstoy, Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Thoreau is sometimes cited as an individualist anarchist. Though Civil Disobedience seems to call for improving rather than abolishing government – "I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government" –

the direction of this improvement points toward anarchism: "'That

government is best which governs not at all;' and when men are prepared

for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have."

Richard Drinnon partly blames Thoreau for the ambiguity, noting that

Thoreau's "sly satire, his liking for wide margins for his writing, and

his fondness for paradox provided ammunition for widely divergent

interpretations of 'Civil Disobedience.'"

He was born David Henry Thoreau in Concord, Massachusetts, into the "modest New England family" of John Thoreau (a pencil maker) and Cynthia Dunbar. His paternal grandfather was of French origin and was born in Jersey. His maternal grandfather, Asa Dunbar, led Harvard's 1766 student "Butter Rebellion", the first recorded student protest in the Colonies. David Henry was named after a recently deceased paternal uncle, David Thoreau. He did not become "Henry David" until after college, although he never petitioned to make a legal name change. He had two older siblings, Helen and John Jr., and a younger sister, Sophia. Thoreau's birthplace still exists on Virginia Road in Concord and is currently the focus of preservation efforts. The house is original, but it now stands about 100 yards away from its first site.

Thoreau studied at Harvard University between 1833 and 1837. He lived in Hollis Hall and took courses in rhetoric,

classics, philosophy, mathematics, and science. A legend proposes that

Thoreau refused to pay the five - dollar fee for a Harvard diploma. In

fact, the master's degree he declined to purchase had no academic merit:

Harvard College

offered it to graduates "who proved their physical worth by being alive

three years after graduating, and their saving, earning, or inheriting

quality or condition by having Five Dollars to give the college." His comment was: "Let every sheep keep its own skin", a reference to the tradition of diplomas being written on sheepskin vellum.

Amos Bronson Alcott and Thoreau's aunt each wrote that "Thoreau" is pronounced like the word "thorough", whose standard American pronunciation rhymes with "furrow". However, Edward Emerson wrote that the name should be pronounced "Thó-row, the h sounded, and accent on the first syllable."

In appearance he was homely, with a nose that he called "my most prominent feature." Of his face, Nathaniel Hawthorne

wrote: "[Thoreau] is as ugly as sin, long - nosed, queer - mouthed, and

with uncouth and rustic, though courteous manners, corresponding very

well with such an exterior. But his ugliness is of an honest and

agreeable fashion, and becomes him much better than beauty." Thoreau also wore a neck - beard for many years, which he insisted many women found attractive. However, Louisa May Alcott mentioned to Ralph Waldo Emerson that Thoreau's facial hair "will most assuredly deflect amorous advances and preserve the man's virtue in perpetuity."

The traditional professions open to college graduates — law, the church, business, medicine — failed to interest Thoreau, so in 1835 he took a leave of absence from Harvard, during which he taught school in Canton, Massachusetts. After he graduated in 1837, he joined the faculty of the Concord public school, but resigned after a few weeks rather than administer corporal punishment. He and his brother John then opened a grammar school in Concord in 1838 called Concord Academy. They introduced several progressive concepts, including nature walks and visits to local shops and businesses. The school ended when John became fatally ill from tetanus in 1842 after cutting himself while shaving. He died in his brother Henry's arms.

Upon graduation Thoreau returned home to Concord, where he met Ralph Waldo Emerson through a mutual friend. Emerson took a paternal and at times patronizing interest in Thoreau, advising the young man and introducing him to a circle of local writers and thinkers, including Ellery Channing, Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne and his son Julian Hawthorne, who was a boy at the time.

Emerson urged Thoreau to contribute essays and poems to a quarterly periodical, The Dial, and Emerson lobbied editor Margaret Fuller to publish those writings. Thoreau's first essay published there was Aulus Persius Flaccus, an essay on the playwright of the same name, published in The Dial in July 1840. It consisted of revised passages from his journal, which he had begun keeping at Emerson's suggestion. The first journal entry on October 22, 1837, reads, "'What are you doing now?' he asked. 'Do you keep a journal?' So I make my first entry to-day."

Thoreau was a philosopher of nature and its relation to the human condition. In his early years he followed Transcendentalism, a loose and eclectic idealist

philosophy advocated by Emerson, Fuller, and Alcott. They held that an

ideal spiritual state transcends, or goes beyond, the physical and

empirical, and that one achieves that insight via personal intuition

rather than religious doctrine. In their view, Nature is the outward

sign of inward spirit, expressing the "radical correspondence of visible

things and human thoughts," as Emerson wrote in Nature (1836).

On April 18, 1841, Thoreau moved into the Emerson house. There, from 1841 – 1844, he served as the children's tutor, editorial assistant, and repair man / gardener. For a few months in 1843, he moved to the home of William Emerson on Staten Island, and tutored the family sons while seeking contacts among literary men and journalists in the city who might help publish his writings, including his future literary representative Horace Greeley.

Thoreau returned to Concord and worked in his family's pencil factory, which he continued to do for most of his adult life. He rediscovered the process to make a good pencil out of inferior graphite by using clay as the binder; this invention improved upon graphite found in New Hampshire and bought in 1821 by relative Charles Dunbar. (The process of mixing graphite and clay, known as the Conté process, was patented by Nicolas - Jacques Conté in 1795). His other source had been Tantiusques, an Indian operated mine in Sturbridge, Massachusetts. Later, Thoreau converted the factory to produce plumbago (graphite), which was used to ink typesetting machines.

Once back in Concord, Thoreau went through a restless period. In

April 1844 he and his friend Edward Hoar accidentally set a fire that

consumed 300 acres (1.2 km2) of Walden Woods.

He spoke often of finding a farm to buy or lease, which he felt would

give him a means to support himself while also providing enough solitude

to write his first book.

| “ | I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan - like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion. | ” |

|

— Henry David Thoreau, Walden, "Where I Lived, and What I Lived For" |

Thoreau needed to concentrate and get himself working more on his writing. In March 1845, Ellery Channing told Thoreau, "Go out upon that, build yourself a hut, & there begin the grand process of devouring yourself alive. I see no other alternative, no other hope for you." Two months later, Thoreau embarked on a two - year experiment in simple living on July 4, 1845, when he moved to a small, self built house on land owned by Emerson in a second growth forest around the shores of Walden Pond. The house was in "a pretty pasture and woodlot" of 14 acres (57,000 m2) that Emerson had bought, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from his family home.

On July 24 or July 25, 1846, Thoreau ran into the local tax collector, Sam Staples, who asked him to pay six years of delinquent poll taxes. Thoreau refused because of his opposition to the Mexican - American War and slavery, and he spent a night in jail because of this refusal. (The next day Thoreau was freed, against his wishes, when his aunt paid his taxes.) The experience had a strong impact on Thoreau. In January and February 1848, he delivered lectures on "The Rights and Duties of the Individual in relation to Government" explaining his tax resistance at the Concord Lyceum. Bronson Alcott attended the lecture, writing in his journal on January 26:

-

Heard Thoreau's lecture before the Lyceum on the relation of the individual to the State – an admirable statement of the rights of the individual to self - government, and an attentive audience. His allusions to the Mexican War, to Mr. Hoar's expulsion from Carolina, his own imprisonment in Concord Jail for refusal to pay his tax, Mr. Hoar's payment of mine when taken to prison for a similar refusal, were all pertinent, well considered, and reasoned. I took great pleasure in this deed of Thoreau's.—Bronson Alcott, Journals (1938)

Thoreau revised the lecture into an essay entitled Resistance to Civil Government (also known as Civil Disobedience). In May 1849 it was published by Elizabeth Peabody in the Aesthetic Papers. Thoreau had taken up a version of Percy Shelley's principle in the political poem The Mask of Anarchy (1819), that Shelley begins with the powerful images of the unjust forms of authority of his time – and then imagines the stirrings of a radically new form of social action.

At Walden Pond, he completed a first draft of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, an elegy to his brother, John, that described their 1839 trip to the White Mountains. Thoreau did not find a publisher for this book and instead printed 1,000 copies at his own expense, though fewer than 300 were sold. Thoreau self published on the advice of Emerson, using Emerson's own publisher, Munroe, who did little to publicize the book.

In August 1846, Thoreau briefly left Walden to make a trip to Mount Katahdin in Maine, a journey later recorded in "Ktaadn," the first part of The Maine Woods.

Thoreau left Walden Pond on September 6, 1847. At Emerson's request, he immediately moved back into the Emerson house to help Lidian manage the household while her husband was on an extended trip to Europe. Over several years, he worked to pay off his debts and also continuously revised his manuscript for what, in 1854, he would publish as Walden, or Life in the Woods, recounting the two years, two months, and two days he had spent at Walden Pond. The book compresses that time into a single calendar year, using the passage of four seasons to symbolize human development. Part memoir and part spiritual quest, Walden at first won few admirers, but later critics have regarded it as a classic American work that explores natural simplicity, harmony, and beauty as models for just social and cultural conditions.

American poet Robert Frost wrote of Thoreau, "In one book ... he surpasses everything we have had in America."

John Updike wrote in 2004,

| “ | A century and a half after its publication, Walden has become such a totem of the back - to - nature, preservationist, anti - business, civil - disobedience mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible. | ” |

Thoreau moved out of Emerson's house in July 1848 and stayed at a

home on Belknap Street nearby. In 1850, he and his family moved into a

home at 255 Main Street; he stayed there until his death.

In 1851, Thoreau became increasingly fascinated with natural history and travel / expedition narratives. He read avidly on botany and often wrote observations on this topic into his journal. He admired William Bartram, and Charles Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle. He kept detailed observations on Concord's nature lore, recording everything from how the fruit ripened over time to the fluctuating depths of Walden Pond and the days certain birds migrated. The point of this task was to "anticipate" the seasons of nature, in his words.

He became a land surveyor and continued to write increasingly detailed natural history observations about the 26 square miles (67 km2) township in his journal, a two - million word document he kept for 24 years. He also kept a series of notebooks, and these observations became the source for Thoreau's late natural history writings, such as Autumnal Tints, The Succession of Trees, and Wild Apples, an essay lamenting the destruction of indigenous and wild apple species.

Until the 1970s, literary critics dismissed Thoreau's late pursuits as amateur science and philosophy. With the rise of environmental history and ecocriticism, several new readings of this matter began to emerge, showing Thoreau to be both a philosopher and an analyst of ecological patterns in fields and woodlots. For instance, his late essay, "The Succession of Forest Trees," shows that he used experimentation and analysis to explain how forests regenerate after fire or human destruction, through dispersal by seed bearing winds or animals.

He traveled to Quebec once, Cape Cod four times, and Maine three times; these landscapes inspired his "excursion" books, A Yankee in Canada, Cape Cod and The Maine Woods, in which travel itineraries frame his thoughts about geography, history and philosophy. Other travels took him southwest to Philadelphia and New York City in 1854, and west across the Great Lakes region in 1861, visiting Niagara Falls, Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Mackinac Island. Although provincial in his physical travels, he was extraordinarily well read and vicariously a world traveler. He obsessively devoured all the first hand travel accounts available in his day, at a time when the last unmapped regions of the earth were being explored. He read Magellan and James Cook, the arctic explorers Franklin, Mackenzie and Parry, David Livingstone and Richard Francis Burton on Africa, Lewis and Clark; and hundreds of lesser known works by explorers and literate travelers. Astonishing amounts of global reading fed his endless curiosity about the peoples, cultures, religions and natural history of the world, and left its traces as commentaries in his voluminous journals. He processed everything he read, in the local laboratory of his Concord experience. Among his famous aphorisms is his advice to "live at home like a traveler."

After John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, many prominent voices in the abolitionist movement distanced themselves from Brown, or damned him with faint praise. Thoreau was disgusted by this, and he composed a speech — A Plea for Captain John Brown — which

was uncompromising in its defense of Brown and his actions. Thoreau's

speech proved persuasive: first the abolitionist movement began to

accept Brown as a martyr, and by the time of the American Civil War entire armies of the North were literally singing Brown's praises. As a contemporary biographer of John Brown put it: "If, as Alfred Kazin

suggests, without John Brown there would have been no Civil War, we

would add that without the Concord Transcendentalists, John Brown would

have had little cultural impact."

Thoreau contracted tuberculosis in 1835 and suffered from it sporadically afterwards. In 1859, following a late night excursion to count the rings of tree stumps during a rain storm, he became ill with bronchitis. His health declined over three years with brief periods of remission, until he eventually became bedridden. Recognizing the terminal nature of his disease, Thoreau spent his last years revising and editing his unpublished works, particularly The Maine Woods and Excursions, and petitioning publishers to print revised editions of A Week and Walden. He also wrote letters and journal entries until he became too weak to continue. His friends were alarmed at his diminished appearance and were fascinated by his tranquil acceptance of death. When his aunt Louisa asked him in his last weeks if he had made his peace with God, Thoreau responded: "I did not know we had ever quarreled."

Aware he was dying, Thoreau's last words were "Now comes good sailing", followed by two lone words, "moose" and "Indian". He died on May 6, 1862 at age 44. Bronson Alcott planned the service and read selections from Thoreau's works, and Channing presented a hymn. Emerson wrote the eulogy spoken at his funeral. Originally buried in the Dunbar family plot, he and members of his immediate family were eventually moved to Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts.

Thoreau's friend Ellery Channing published his first biography, Thoreau the Poet - Naturalist,

in 1873, and Channing and another friend Harrison Blake edited some

poems, essays, and journal entries for posthumous publication in the

1890s. Thoreau's journals, which he often mined for his published works

but which remained largely unpublished at his death, were first

published in 1906 and helped to build his modern reputation. A new,

expanded edition of the journals is underway, published by Princeton

University Press. Today, Thoreau is regarded

as one of the foremost American writers, both for the modern clarity of

his prose style and the prescience of his views on nature and politics.

His memory is honored by the international Thoreau Society.

"Most of the luxuries and many of the so - called comforts of life are not only not indispensable, but positive hindrances to the elevation of mankind."— Thoreau

Thoreau was an early advocate of recreational hiking and canoeing, of conserving natural resources on private land, and of preserving wilderness as public land. Thoreau was also one of the first American supporters of Darwin's theory of evolution. He was not a strict vegetarian, though he said he preferred that diet and advocated it as a means of self - improvement. He wrote in Walden: "The practical objection to animal food in my case was its uncleanness; and besides, when I had caught and cleaned and cooked and eaten my fish, they seemed not to have fed me essentially. It was insignificant and unnecessary, and cost more than it came to. A little bread or a few potatoes would have done as well, with less trouble and filth."

Thoreau neither rejected civilization nor fully embraced wilderness. Instead he sought a middle ground, the pastoral

realm that integrates both nature and culture. His philosophy required

that he be a didactic arbitration between the wilderness he based so

much on and the spreading mass of North American humanity. He decried

the latter endlessly but felt the teachers need to be close to those who

needed to hear what he wanted to tell them. He was in many ways a

'visible saint', a point of contact with the wilds, even if the land he

lived on had been given to him by Emerson and was far from cut-off. The

wildness he enjoyed was the nearby swamp or forest, and he preferred

"partially cultivated country." His idea of being "far in the recesses

of the wilderness" of Maine was to "travel the logger's path and the

Indian trail," but he also hiked on pristine untouched land. In the

essay "Henry David Thoreau, Philosopher" Roderick Nash

writes: "Thoreau left Concord in 1846 for the first of three trips to

northern Maine. His expectations were high because he hoped to find

genuine, primeval America. But contact with real wilderness in Maine

affected him far differently than had the idea of wilderness in Concord.

Instead of coming out of the woods with a deepened appreciation of the

wilds, Thoreau felt a greater respect for civilization and realized the

necessity of balance."

On alcohol, Thoreau wrote: "I would fain keep sober always... I believe

that water is the only drink for a wise man; wine is not so noble a

liquor... Of all ebriosity, who does not prefer to be intoxicated by the

air he breathes?"

"Thoreau's careful observations and devastating conclusions have rippled into time, becoming stronger as the weaknesses Thoreau noted have become more pronounced ... Events that seem to be completely unrelated to his stay at Walden Pond have been influenced by it, including the national park system, the British labor movement, the creation of India, the civil rights movement, the hippie revolution, the environmental movement, and the wilderness movement. Today, Thoreau's words are quoted with feeling by liberals, socialists, anarchists, libertarians and conservatives alike."— Ken Kifer

Thoreau's political writings had little impact during his lifetime, as "his contemporaries did not see him as a theorist or as a radical, viewing him instead as a naturalist. They either dismissed or ignored his political essays, including Civil Disobedience. The only two complete books (as opposed to essays) published in his lifetime, Walden and A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849), both dealt with nature, in which he loved to wander." Nevertheless, Thoreau's writings went on to influence many public figures. Political leaders and reformers like Mahatma Gandhi, President John F. Kennedy, civil rights activist Martin Luther King, Jr., Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, and Russian author Leo Tolstoy all spoke of being strongly affected by Thoreau's work, particularly Civil Disobedience, as did "right - wing theorist Frank Chodorov [who] devoted an entire issue of his monthly, Analysis, to an appreciation of Thoreau." Thoreau also influenced many artists and authors including Edward Abbey, Willa Cather, Marcel Proust, William Butler Yeats, Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, Upton Sinclair, E.B. White, Lewis Mumford, Frank Lloyd Wright, Alexander Posey and Gustav Stickley. Thoreau also influenced naturalists like John Burroughs, John Muir, E. O. Wilson, Edwin Way Teale, Joseph Wood Krutch, B.F. Skinner, David Brower and Loren Eiseley, whom Publishers Weekly called "the modern Thoreau." English writer Henry Stephens Salt wrote a biography of Thoreau in 1890, which popularized Thoreau's ideas in Britain: George Bernard Shaw, Edward Carpenter and Robert Blatchford were among those who became Thoreau enthusiasts as a result of Salt's advocacy.

Mahatma Gandhi first read Walden in 1906 while working as a civil rights activist in Johannesburg, South Africa. He first read Civil Disobedience "while he sat in a South African prison for the crime of nonviolently protesting discrimination against the Indian population in the Transvaal. The essay galvanized Gandhi, who wrote and published a synopsis of Thoreau's argument, calling its 'incisive logic . . . unanswerable' and referring to Thoreau as 'one of the greatest and most moral men America has produced.'" He told American reporter Webb Miller, "[Thoreau's] ideas influenced me greatly. I adopted some of them and recommended the study of Thoreau to all of my friends who were helping me in the cause of Indian Independence. Why I actually took the name of my movement from Thoreau's essay 'On the Duty of Civil Disobedience,' written about 80 years ago."

Martin Luther King, Jr. noted in his autobiography that his first encounter with the idea of non - violent resistance was reading "On Civil Disobedience" in 1944 while attending Morehouse College. He wrote in his autobiography that it was

Here, in this courageous New Englander's refusal to pay his taxes and his choice of jail rather than support a war that would spread slavery's territory into Mexico, I made my first contact with the theory of nonviolent resistance. Fascinated by the idea of refusing to cooperate with an evil system, I was so deeply moved that I reread the work several times.

I became convinced that noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good. No other person has been more eloquent and passionate in getting this idea across than Henry David Thoreau. As a result of his writings and personal witness, we are the heirs of a legacy of creative protest. The teachings of Thoreau came alive in our civil rights movement; indeed, they are more alive than ever before. Whether expressed in a sit-in at lunch counters, a freedom ride into Mississippi, a peaceful protest in Albany, Georgia, a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, these are outgrowths of Thoreau's insistence that evil must be resisted and that no moral man can patiently adjust to injustice.

American psychologist B.F. Skinner wrote that he carried a copy of Thoreau's Walden with him in his youth and, in 1945, wrote Walden Two, a fictional utopia about 1,000 members of a community living together inspired by the life of Thoreau. Thoreau and his fellow Transcendentalists from Concord were a major inspiration of the composer Charles Ives. The 4th movement of the Concord Sonata for piano (with a part for flute, Thoreau's instrument) is a character picture and he also set Thoreau's words.

Thoreau's ideas have impacted and resonated with various strains in the anarchist movement, with Emma Goldman referring to him as "the greatest American anarchist." Green anarchism and Anarcho - primitivism in particular have both derived inspiration and ecological points - of - view from the writings of Thoreau. John Zerzan included Thoreau's text "Excursions" (1863) in his edited compilation of works in the anarcho - primitivist tradition titled Against civilization: Readings and reflections. Additionally, Murray Rothbard, the founder of anarcho - capitalism, has opined that Thoreau was one of the "great intellectual heroes" of his movement. Thoreau was also an important influence on late 19th century anarchist naturism. While globally, Thoreau's concepts also held importance within individualist anarchist circles in Spain, France and Portugal.

Although his writings would later receive widespread acclaim, Thoreau's ideas were not universally applauded by some of his contemporaries in literary circles. Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson judged Thoreau's endorsement of living alone and apart from modern society in natural simplicity to be a mark of "unmanly" effeminacy and "womanish solitude", while deeming him a self - indulgent "skulker." Nathaniel Hawthorne was also critical of Thoreau, writing that he "repudiated all regular modes of getting a living, and seems inclined to lead a sort of Indian life among civilized men." In a similar vein, poet John Greenleaf Whittier detested what he deemed to be the "wicked" and "heathenish" message of Walden, decreeing that Thoreau wanted man to "lower himself to the level of a woodchuck and walk on four legs."

In response to such criticisms, English novelist George Eliot, writing for the Westminster Review, characterized such critics as uninspired and narrow - minded:

People — very wise in their own eyes — who would have every man's life ordered according to a particular pattern, and who are intolerant of every existence the utility of which is not palpable to them, may pooh-pooh Mr. Thoreau and this episode in his history, as unpractical and dreamy.