<Back to Index>

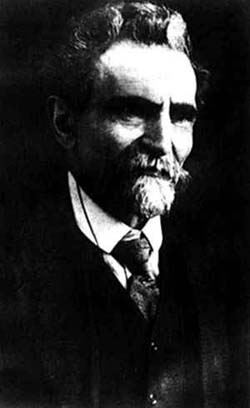

- Social and Political Activist Errico Malatesta, 1853

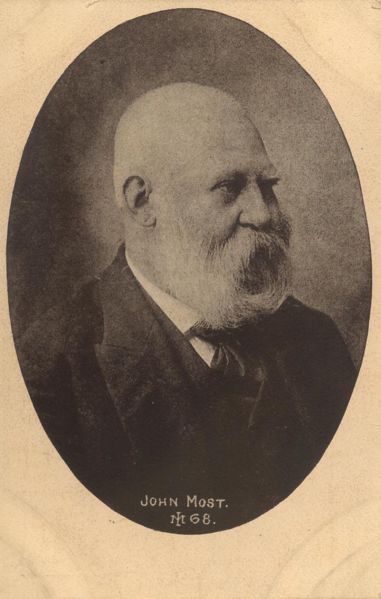

- Politician and Newspaper Editor Johann Joseph Most, 1846

PAGE SPONSOR

Errico Malatesta (December 14, 1853 – July 22, 1932) was an Italian anarcho - communist. He was an insurrectionary anarchist early in his life. He spent much of his life exiled from his homeland of Italy and in total spent more than ten years in prison. He wrote and edited a number of radical newspapers and was also a friend of Mikhail Bakunin. He was an enormously popular figure in his time. According to anarchist journalist Brian Doherty, "Malatesta could get tens of thousands, sometimes more than 100,000, fans to show up whenever [he] arrived in town."

Malatesta was born in Santa Maria Capua Vetere, in the province of Caserta (southern Italy). The first of a long series of arrests came at just fourteen, when he was apprehended for writing a letter to King Victor Emmanuel II that complained about local injustice.

Malatesta was introduced to Mazzinian Republicanism while studying medicine at the University of Naples; however, he was expelled from the university in 1871 for joining a demonstration. Partly via his enthusiasm for the Paris Commune and partly via his friendship with Carmelo Palladino, he joined the Naples section of the International Workingmen's Association that same year, as well as teaching himself to be a mechanic and electrician. In 1872 he met Mikhail Bakunin, with whom he participated in the St Imier congress of the International. For the next four years, Malatesta helped spread Internationalist propaganda in Italy; he was imprisoned twice for these activities.

In April 1877, Malatesta, Carlo Cafiero, the Russian Stepniak and about 30 others started an insurrection in the province of Benevento, taking the villages of Letino and Gallo without a struggle. The revolutionaries burned tax registers and declared the end of the King's reign, and were met by enthusiasm: even a local priest showed his support. After leaving Gallo, however, they were arrested by government troops and held for sixteen months before being acquitted. After a number of terrorist attacks on the Italian royal family and their supporters, the radicals were kept under constant surveillance by the police. Even though the anarchists claimed to have no connection to the attacks, Malatesta, being an advocate of social revolution, was included in this surveillance. After returning to Naples, he was forced to leave Italy altogether because of these conditions, beginning a long period of exile.

He went to Egypt briefly, visiting some Italian friends but was soon expelled by the Italian Consul. After working his passage on a French ship and being refused entry to Syria, Turkey and Italy, he landed in Marseille from where he made his way to Geneva in Switzerland – then something of an anarchist center. Here he befriended Elisée Reclus and Peter Kropotkin, helping the latter to produce La Révolte. However, he was soon expelled from Switzerland, and eventually traveled to London in 1880, passing through Romania, Paris and Belgium.

In London, Malatesta worked as an ice cream seller and a mechanic, and participated in the 1872 congress of the International, which gave birth to the Anarchist St. Imier International.

He went to fight the British colonial troops in Egypt in 1882, then secretly returned to Italy the following year. In Florence he founded the weekly anarchist paper La Questione Sociale (The Social Question) in which his most popular pamphlet, Fra Contadini (Among Farmers), first appeared. Malatesta went back to Naples in 1884 — while waiting to serve a three year prison term — to nurse the victims of a cholera epidemic. Once again, he fled Italy to escape imprisonment and went to South America. He lived in Buenos Aires in 1885, where he resumed publication of La Questione Sociale, and was involved in the founding of the first militant workers' union in Argentina, the Bakers Union, and left an anarchist impression in the workers' movements there for years to come.

Returning to Europe in 1889, he published a newspaper called L'Associazione in Nice until he was forced to flee to London. For the next eight years Malatesta was based in London, but made clandestine trips to France, Switzerland and Italy and went on a lecture tour of Spain with Fernando Tarrida del Mármol. During this time he wrote several important pamphlets, including L'Anarchia. Malatesta then took part in the International Anarchist Congress of Amsterdam (1907), where he debated in particular with Pierre Monatte on the relation between anarchism and syndicalism (or trade - unionism). The latter thought that syndicalism was revolutionary and would create the conditions of a social revolution, while Malatesta considered that syndicalism by itself was not sufficient. Malatesta thought that trade unions were reformist, and could even be, at times, conservative. Along with Christiaan Cornelissen, he cited as example US trade unions, where trade unions composed of qualified workers sometimes opposed themselves to non - qualified workers in order to defend their relatively privileged position. In 1912, Malatesta appeared in Bow Street Police Court on a criminal libel charge, which resulted in a 3 month prison sentence, and his recommendation for deportation. This order was quashed following campaigning by the radical press and demonstrations by workers organizations.

After the First World War,

Malatesta eventually returned to Italy for the final time. Two years

after his return, in 1921, the Italian government imprisoned him, again,

although he was released two months before the fascists came to power. From 1924 until 1926, when Benito Mussolini silenced all independent press, Malatesta published the journal Pensiero e Volontà,

although he was harassed and the journal suffered from government

censorship. He was to spend his remaining years leading a relatively

quiet life, earning a living as an electrician. After years of suffering

from a weak respiratory system and regular bronchial attacks, he developed bronchial pneumonia

from which he died after a few weeks, despite being given 1500 liters

of oxygen in his last five hours. He died on Friday, 22 July 1932. He

was an atheist.

Malatesta is difficult to place within the spectrum of the various political camps within anarchism both because his politics changed over time and because he did not identify himself strongly with any of the various groupings.

His constant work as an organizer and speaker embodied his ideals of

free association: for Malatesta, it was useful to join an organization only for the purpose of doing something with that group of people. There was no sense in belonging to a group simply to belong.

His arguments with Monatte at at the Amsterdam Conference of 1907 against pure syndicalism were later developed in a series of articles against the doctrine of revolutionary unions known as anarcho - syndicalism, saying “I am against syndicalism, both as a doctrine and a practice, because it strikes me as a hybrid creature.” He advocated activity in the trade unions, both because they were necessary for the organization and self defense of workers under a capitalist state regime, and as a way of reaching broader masses. Anarchists should have discussion groups in unions, as in factories, barracks and schools, but “anarchists should not want the unions to be anarchist.”

He thought Syndicalism, like all unions, was by nature reformist. While anarchists should be active in the rank and file, he said “any anarchist who has agreed to become a permanent and salaried official of a trade union is lost to anarchism.”

While some anarchists wanted to split from conservative unions to

form revolutionary syndicalist unions, Malatesta predicted they would

either remain an “affinity group” with no influence, or go through the

same process of bureaucratization as the unions they left.

This early statement of what would come to be known as "the

rank - and - file strategy" remained a minority position within anarchism,

but Malatesta’s ideas did have echoes in the anarchists Jean Grave and Vittorio Aurelio.

Malatesta was a committed revolutionary: he believed that the anarchist revolution was coming soon, and that violence would be a necessary part of it since the state rested ultimately on violent coercion. As he wrote in his article "The Revolutionary 'Haste'":

- It is our aspiration and our aim that everyone should become socially conscious and effective; but to achieve this end, it is necessary to provide all with the means of life and for development, and it is therefore necessary to destroy with violence, since one cannot do otherwise, the violence which denies these means to the workers. (Umanità Nova, number 125, September 6, 1921)

Malatesta, then, advocated violence as a "necessary" part of the emancipation of the working class.

Johann Joseph Most (February 5, 1846 in Augsburg, Bavaria – March 17, 1906 in Cincinnati, Ohio) was a German - American politician, newspaper editor, and orator. He is credited with popularizing the concept of "Propaganda of the deed". His grandson was Boston Celtics radio play - by - play man Johnny Most.

According to biographer Frederic Trautmann, Most was born out of wedlock to a governess and a clerk. His mother died of cholera when Most was very young. Most was subjected to physical abuse by his stepmother and a schoolteacher; his aversion to religion earned him more beatings at school. To the end of his life Most was "a militant atheist with the zeal of a religious fanatic" who "knew more Scripture than many clergymen knew".

Most developed frostbite on the left side of his face as a child. For several years thereafter, flesh rotted and infection spread, with the primitive medicine of the day unable to treat the condition. His condition worsened and Most was diagnosed with terminal cancer. As a last - gasp measure a surgeon was called in, who opened the left side of Most's face, removing infection, flesh, and bone before crudely stitching up the wound. The grotesque physical effects of the surgeon's handiwork would mark Most's visage for the rest of his life.

Most was apprenticed to a bookbinder, for whom he had to bind books from dawn until sunset, a condition which Most later likened to slavery. At the age of 17 he became a journeyman bookbinder and plied his trade from town to town and job to job, working in 50 cities in 6 countries from 1863 to 1868. In Vienna he was fired and placed on a blacklist

for having staged a strike. Unemployable in his trade, he learned to

make wooden boxes for hats, cigars and matches, which he sold on the

street until police brought an end to his trade for lacking a license.

As the 1860s drew to a close, Most was won over to the ideas of international socialism, an emerging political movement in Germany and Austria. Most saw in the doctrines of Karl Marx and Ferdinand Lassalle a blueprint for a new egalitarian society and became a fervid supporter of the Social Democracy, as the Marxist movement was known in the day.

Most engaged himself as editor of socialist newspapers in Chemnitz and Vienna, both suppressed by the authorities, and of the Berliner Freie Presse (Berlin Free Press). Most was a dedicated advocate of revolutionary socialism, sharing the views expressed by Wilhelm Liebknecht in an 1869 speech that "Socialism cannot be realized within the present state. Socialism must overturn the present state."

In 1873, Most wrote a summary of Karl Marx's Das Kapital. At Liebknecht's request, Marx and Friedrich Engels made some corrections to Most's text for a second edition published in 1876, despite the fact that the pair did not believe the pamphlet represented a satisfactory summary of Marx's work.

In 1874, Most was elected as a Social Democratic deputy in the German Reichstag, in which he served until 1878.

Most was repeatedly arrested for his attacks on patriotism and conventional religion and ethics, and for his gospel of terrorism, preached in prose and in many songs such as those in his Proletarier - Liederbuch (Proletarian Songbook). Some of his experiences in prison were recounted in the 1876 work, Die Bastille am Plötzensee: Blätter aus meinem Gefängniss - Tagebuch (The Bastille on Plötzensee: Pages from my Prison Diary).

After advocating violent action, including the use of explosive bombs, as a mechanism to bring about revolutionary change, Most was forced into exile by the government. He went to France but was forced to leave at the end of 1878, settling in London. There he founded his own newspaper, Freiheit (Freedom), with the first issue coming off the press dated January 4, 1879. Convinced by his own experience of the futility of parliamentary action, Most began to espouse the doctrine of anarchism, which led to his expulsion from the German Social Democratic Party in 1880.

In June 1881, Most expressed his delight in the pages of the Freiheit over the assassination of Alexander II of Russia and advocated its emulation; for this Most was imprisoned by British authorities for a year and a half.

Encouraged by news of labor struggles and industrial disputes in the United States, Most emigrated to the USA upon his release from prison in 1882. He promptly began agitating in his adopted land among other German émigrés. Among his associates was August Spies, one of the anarchists hanged for conspiracy in the Haymarket Square bombing, whose desk police found to contain an 1884 letter from Most promising a shipment of "medicine," his code word for dynamite.

Most resumed the publication of the Freiheit in New York. He was imprisoned in 1886, again in 1887, and in 1902, the last time for two months for publishing after the assassination of President McKinley an editorial in which he argued that it was no crime to kill a ruler.

"Whoever looks at America will see: the ship is powered by stupidity, corruption, or prejudice," Most said.

Most initially advocated traditional collectivist anarchism, but later embraced anarchist communism. According to right wing libertarian Jeff Riggenbach:

Most's approach to anarchism stressed two main ideas: first, that it was necessary to abolish not only the state, but also the social institutions known as private property and the free market; second, that the intelligent anarchist must avail himself of what Most and many other anarchists of the time called "propaganda of the deed" — acts of violence that would inspire the masses and sweep them up in revolutionary fervor.

Most was famous for stating the concept of the Propaganda of the Deed (Attentat): "The existing system will be quickest and most radically overthrown by the annihilation of its exponents. Therefore, massacres of the enemies of the people must be set in motion." Most is best known for a pamphlet published in 1885: The Science of Revolutionary Warfare, a how - to manual on the subject of bomb making which earned the author the moniker "Dynamost."

A gifted orator, Most propagated these ideas throughout Marxist and anarchist circles in the United States and attracted many adherents, most notably Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman.

Inspired by Most's theories of Attentat, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman, enraged by the deaths of workers during the Homestead strike, put words into action with Berkman's attempted assassination of Homestead factory manager Henry Clay Frick in 1892. Berkman and Goldman were soon disillusioned as Most became one of Berkman's most outspoken critics. In Freiheit, Most attacked both Goldman and Berkman, implying Berkman's act was designed to arouse sympathy for Frick. Goldman's biographer Alice Wexler suggests that Most's criticisms may have been inspired by jealousy of Berkman. Goldman was enraged, and demanded that Most prove his insinuations. When he refused to respond, she confronted him at next lecture. After he refused to speak to her, she lashed him across the face with a horsewhip, broke the whip over her knee, then threw the pieces at him. She later regretted her assault, confiding to a friend, "At the age of twenty - three, one does not reason."

Most was in Cincinnati, Ohio, to give a speech when he fell ill. Diagnosed with erysipelas, doctors could do little for him, and he died a few days later.