<Back to Index>

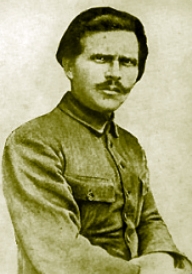

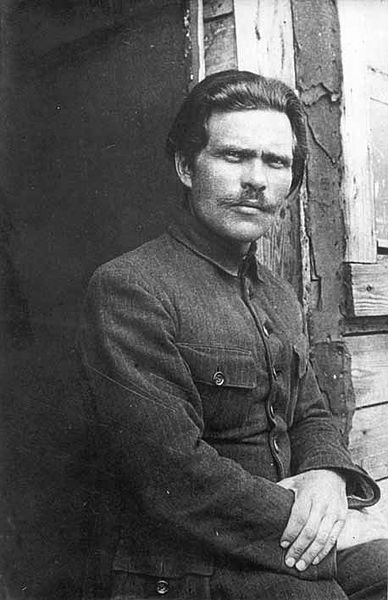

- Anarcho - Communist Revolutionary Nestor Ivanovych Makhno, 1888

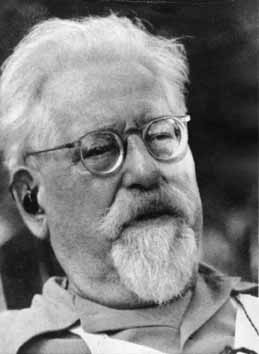

- Anarcho - Syndicalist Writer and Activist Johann Rudolf Rocker, 1873

PAGE SPONSOR

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno or simply Daddy Makhno (Ukrainian: Нестор Іванович Махно, Russian: Не́стор Ива́нович Махно́; October 26 [O.S. October 14] 1888 – July 6, 1934) was a Ukrainian anarcho - communist guerrilla leader turned army commander who led an independent anarchist army in Ukraine during the Russian Civil War.

A commander of the peasant Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine, also known as the Anarchist Black Army, Makhno led a guerrilla campaign during the Russian Civil War. He supported the Bolsheviks, the Ukrainian Directory,

the Bolsheviks again, and then turned to organizing the Free Territory

of Ukraine, an anarchist society. This project was cut short by the

consolidation of Bolshevik power. Makhno was described by anarchist

theorist Emma Goldman as "an extraordinary figure" leading a

revolutionary peasants' movement. He is also credited as the inventor of

the tachanka, a horse drawn platform mounting a heavy machine gun.

Nestor Makhno was born into a poor peasant family in Huliaipole, Yekaterinoslav Governorate in the Novorossiya region of the Russian Empire (now Zaporizhia Oblast, Ukraine). He was the youngest of five children. Church files show a baptism date of October 27 (November 8), 1888; but Nestor Makhno's parents registered his date of birth as 1889 (in an attempt to postpone conscription).

His father died when he was ten months old. Due to extreme poverty, he had to work as a shepherd at the age of seven. He studied at the Second Huliaipole primary school in winter at the age of eight and worked for local landlords during the summer. He left school at the age of twelve and was employed as a farmhand on the estates of nobles and on the farms of wealthy peasants or kulaks.

At the age of seventeen, he was employed in Huliaipole itself as an

apprentice painter, then as a worker in a local iron foundry and

ultimately as a foundryman in the same organization. During this time he

became involved in revolutionary politics. His involvement was based on

his experiences of injustice at work and the terrorism of the Tsarist regime during the 1905 revolution. In 1906, Makhno joined the anarchist organization in Huliaipole.

He was arrested in 1906, tried, and acquitted. He was again arrested in

1907, but could not be incriminated, and the charges were dropped. The third arrest came in 1908 when an infiltrator was able to testify against Makhno. In 1910 Makhno was sentenced to death by hanging, but the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment and he was sent to Butyrskaya prison in Moscow. In prison he came under the influence of his intellectual cellmate Piotr Arshinov. He was released from prison after the February Revolution in 1917.

After liberation from prison, Makhno organized a peasants' union. It gave him a "Robin Hood" image and he expropriated large estates from landowners and distributed the land among the peasants.

In March 1918, the new Bolshevik government in Russia signed the Treaty of Brest - Litovsk concluding peace with the Central Powers, but ceding large amounts of territory, including Ukraine. As the Central Rada of the Ukrainian People's Republic (UNR) was unable to maintain order, a coup by former Tsarist general Pavlo Skoropadsky resulted in the establishment of the Hetmanate. Already dissatisfied by the UNR's failure to resolve the question of land ownership, much of the peasantry refused to support a conservative government administered by former imperial officials and supported by the Austro - Hungarian and German occupiers. Peasant bands under various self - appointed otamany which had been counted on the rolls of the UNR's army now attacked the Germans, later going over to the Directory in summer 1918 or the Bolsheviks in late 1918 – 19, or home to protect local interests, in many cases changing allegiances, plundering so-called class enemies, and venting age old resentments. They finally dominated the countryside in mid 1919; the largest portion would follow either Socialist Revolutionary Matviy Hryhoriyiv or the anarchist flag of Makhno.

In Yekaterinoslav province, the rebellion soon took on anarchist political overtones. Nestor Makhno joined one of such groups (headed by sailor - deserter Fedir Shchus) and eventually became its commander. Due in part to the impressive personality and charisma of Makhno, all Ukrainian anarchist detachments and peasant guerrilla bands in the region were subsequently known as Makhnovists (Russian: махновцы). These were eventually united into the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine (RIAU), also called the Black Army (because they fought under the anarchist black flag). The RIAU battled against the Whites (counter - revolutionaries) forces, Ukrainian nationalists, and various independent paramilitary formations that conducted anti - semitic pogroms. The anarchist movement in Ukraine came to be referred to as the Black Army, Makhnovism or pejoratively Makhnovshchina.

In areas where they drove out opposing armies, villagers (and

workers) sought to abolish capitalism and the state by organizing

themselves into village assemblies, communes

and free councils. The land and factories were expropriated and put

under nominal peasant and worker control by means of self - governing

committees; however, town mayors and many officials were drawn directly

from the ranks of Makhno's military and political leadership.

Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky, head of a the Ukrainian State, (considered by most historians as a puppet regime) lost the support of the Central Powers (Germany and Austro - Hungary, which had armed his forces and installed him in power) after the collapse of the German western front. Unpopular among most southern Ukrainians, the Hetman saw his best forces evaporate, and was driven out of Kiev by the Directory. In March 1918, Makhno's forces and allied anarchist and guerrilla groups won victories against German, Austrian and Ukrainian nationalist (the army of Symon Petlura) forces, and units of the White Army, capturing a lot of German and Austro - Hungarian arms. These victories over much larger enemy forces established Makhno's reputation as a military tactician; he became known as Batko (‘Father’) to his admirers.

At this point, the emphasis on military campaigns that Makhno had adopted in the previous year shifted to political concerns. The first Congress of the Confederation of Anarchists Groups, under the name of Nabat ("the Alarm Drum"), issued five main principles: rejection of all political parties, rejection of all forms of dictatorships (including the dictatorship of the proletariat, viewed by Makhnovists and many anarchists of the day as a term synonymous with the dictatorship of the Bolshevik communist party), negation of any concept of a central state, rejection of a so-called "transitional period" necessitating a temporary dictatorship of the proletariat, and self - management of all workers through free local workers' councils (soviets). While the Bolsheviks argued that their concept of dictatorship of the proletariat meant precisely "rule by workers' councils," the Makhnovist platform opposed the "temporary" Bolshevik measure of "party dictatorship." The Nabat was by no means a puppet of Mahkno and his supporters, from time to time criticizing the Black Army and its conduct in the war.

In 1918, after recruiting large numbers of Ukrainian peasants, as well as numbers of Jews, anarchists, naletchki, and recruits arriving from other countries, Makhno formed the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine, otherwise known as the Anarchist Black Army. At its formation, the Black Army consisted of about 15,000 armed troops, including infantry and cavalry (both regular and irregular) brigades; artillery detachments were incorporated into each regiment. From November 1918 to June 1919, using the Black Army to secure its hold on power, the Makhnovists attempted to create an anarchist society in Ukraine, administered at the local level by autonomous peasants' and workers' councils.

The agricultural part of these villages was composed of peasants, someone understood at the same time peasants and workers. They were founded first of all on equality and solidarity of his members. All, men and women, worked together with a perfect conscience that they should work on fields or that they should be used in housework... Working program was established in meetings where all participated. They knew then exactly what they had to make.

—Makhno, Russian Revolution in Ukraine

New relationships and values were generated by this new social paradigm, which led Makhnovists to formalize the policy of free communities as the highest form of social justice. Education was organized on Francisco Ferrer's principles, and the economy was based upon free exchange between rural and urban communities, from crop and cattle to manufactured products, according to the science proposed by Peter Kropotkin.

Makhno called the Bolsheviks dictators and opposed the "Cheka [secret police]... and similar compulsory authoritative and disciplinary institutions" and called for "[f]reedom of speech, press, assembly, unions and the like". The Bolsheviks accused the Makhnovists of imposing a formal government over the area they controlled, and also said that Makhnovists used forced conscription, committed summary executions, and had two military and counter - intelligence forces: the Razvedka and the Kommissiya Protivmakhnovskikh Del (patterned after the Cheka and the GRU). However, later historians have dismissed these claims as fraudulent propaganda.

The Bolsheviks claimed that it would be impossible for a small,

agricultural society to organize into an anarchist society so quickly.

However, Eastern Ukraine had a large amount of coal mines, and was one of the most industrialized parts of the Russian Empire.

The image of Makhno as leader of the peasant uprising has been called "legendary" and a "colorful personality". However, in the view of the German and German Mennonite community in Ukraine, he was viewed as the instigator of "military ravages", against innocent farmers, an "inhuman monster" whose path is "literally drenched with blood."

During the war, Mahkno and his Black Army raided many German and Mennonite villages and estates in the Katerynoslav Oblast. The larger rural landholdings of pacifist Mennonites were prominent targets. Makhno's anarchist army generally targeted Mennonites because their wealthy and prosperous communal estates were thought of as Kulaks - wealthy and landed gentry with more advantages than the surrounding Ukrainian peasants. Makhno was also staunchly anti - religious, and viewed Mennonites as enemies on these grounds.

While prohibited by their religion from serving in the Tsar's army, many Mennonites had assisted the Tsar's war effort by performing national service in non - fighting roles, including forestry and hospital units. The Mennonites' Germanic background also served to inflame negative sentiment during the period of revolution, as many peasants in the Black Army had families who had suffered previous depredations by German, Austro - Hungarian, and Hetmanist forces (though one of the high commanders of the Makhnovist Army named Klein was said to be of German descent). It is believed that Makhno himself had worked as a cattle herder on a Mennonite estate in his youth and harbored negative feelings based on treatment he had received while employed there.

In 1919, with the advance of General Denikin's White Volunteer Army into Ukraine, depredations and expropriations by Black Army detachments increased, including the burning of crops and destruction of livestock (what was not seized was often destroyed, either to deny supplies to the advancing White armies, or simply out of retaliation). In response and in the context of a complete collapse in government authority, some Mennonites discarded their pledge of non - violence and, together with other German communities, formed self - defence (or Selbstschutz) units. These units were initially somewhat successful in protecting their communities against Makhno's partisans but were overwhelmed once the anarchists aligned themselves with the Red Army, which had entered Ukraine in February 1919. Hundreds of Mennonites were murdered and robbed during this period, primarily in areas surrounding the villages of Chortitza, Zagradovka, and Nikolaipol. The combination of Tsarist resettlement of Germans in World War I and attacks during the civil war reduced the German population from 750,000 in 1914 to 514,000 in 1926. The remainder had their lands expropriated by the Soviet government.

Like the White army, the Ukrainian National Republic and forces loyal to the Bolsheviks, Makhno's forces were accused of conducting pogroms against Jews in Ukraine during the civil war, based on the Bolshevik accounts of the war. However, these claims have never been proven. Paul Avrich writes, "Maknno's alleged anti - Semitism... Charges of Jew - baiting and of anti - Jewish pogroms have come from every quarter, left, right, and center. Without exception, however, they are based on hearsay, rumor, or intentional slander, and remain undocumented and unproved." Avrich notes that a considerable number of Jews took part in the Makhnovist anarchist movement. Some, like Vsevolod Mikhailovich Eikhenbaum, also known as "Voline" were intellectuals who served on the Cultural - Educational Commission, wrote his manifestos, and edited his journals, but the great majority fought in the ranks of the Anarchist Black Army, either in special detachments of Jewish artillery and infantry, or else within the regular anarchist army brigades alongside peasants and workers of Ukrainian, Russian, and other ethnic origins. Together they formed a significant part of Makhno's anarchist army. Significantly, during the Russian civil war, the Merkaz or Central Committee of the Zionist Organization in Russia regularly reported on many armed groups committing pogroms against Jews in Russia, including the Whites, the Russian Ukrainian 'Green' nationalist Nikifor Grigoriev (later shot by Black Army troops on Makhno's orders) as well as Red Army forces, but did not accuse Makhno or the anarchist Black Army of directing pogroms or other attacks against Russian Jews. According to the Cambridge University Press, “He was a self - educated man, committed to the teachings of Bakunin and Kropotkin, and he could not fairly be described as an anti - Semite. Makhno had Jewish comrades and friends; and like Symon Petliura, he issued a proclamation forbidding pogroms.” The book goes on to claim that "the anarchist leader could not or did not impose discipline on his soldiers. In the name of ‘class struggle’ his troops with particular enthusiasm robbed Jews of whatever they had.” This would be in the spirit of standards of behavior which Makhno promoted for his troops, which called for war against "the rich bourgeoisie of all nationalities" be they Russian, Ukrainian or Jewish, as well as his explicit order not to beat or rob "peaceful Jews".

While the bulk of Makhno's forces consisted of ethnic Ukrainian

peasants, he did not consider himself to be a Ukrainian nationalist,

but rather an anarchist. His movement did put out a Ukrainian language

version of their newspaper and his wife Halyna Kuzmenko was a

nationally conscious Ukrainian. In emigration, Makhno came to believe

that anarchists would only have a future in Ukraine if they

Ukrainianized and he stated that he regretted that he was writing his

memoirs in Russian and not in Ukrainian.

Makhno viewed the revolution as an opportunity for ordinary Russians -

particularly rural peasants - to rid themselves of the overweening power

of the central state through self - governing and autonomous peasant

committees, protected by a people's army dedicated to anarchist

principles of self - rule.

Bolshevik hostility to Makhno and his anarchist army increased after the defection of 40,000 Red Army troops in Crimea to the Black Army in July 1918. The Nabat confederation was banned and the Third Congress (specifically Pavel Dybenko) declared the "Makhnovschina" (Ukrainian anarchists) outlaws and counter - revolutionaries. In response, the Anarchist Congress publicly questioned, "[M]ight laws exist as made by few persons so-called revolutionaries, allowing these to declare the outlawing of an entire people which is more revolutionary than them?" (Archinoff, The Makhnovist Movement). Relying largely on a September 1920 report from V. Ivanov, a Bolshevik delegate to Makhno's camp, Moscow justified its hostility to Makhno and the anarchists by claiming that:

- Makhno's anarchist army and state had no free elections to the general command staff, with all commanders up to company commander appointed by Makhno and the Anarchist Revolutionary War Council;

- Makhno had refused to provide food for Soviet railwaymen and telegraph operators (an attempt to capitalize on Makhno's view of railroads as capitalist frivolities);

- there was a ‘special section’ in the Anarchist Revolutionary Military Council constitution that dealt with disobedience and desertion "secretly and without mercy” (this objection was made in spite of the fact that Special Punitive Brigades of the Bolshevist Red Army had already been shooting deserters and members of their families since 1918);

- that Makhno's forces had raided Red Army convoys for supplies, and had failed to pay for an armored car seized from Briansk;

- that the Nabat was responsible for deadly acts of terrorism in Russian cities (a reference to attempts on the lives of Bolshevik officials by independent anarchists and other dissident leftist groups unrelated to either Makhno or the Nabat).

The Bolshevik press was not only silent on the subject of Moscow's continued refusal to send arms to the Black Army, but also failed to credit the Ukrainian anarchists' continued willingness to ship food supplies to the hungry urban residents of Bolshevik held cities.

Lenin soon sent Lev Kamenev

to Ukraine, who conducted a cordial interview with Makhno. After

Kamenev's departure, Makhno claimed to have intercepted two Bolshevik

messages, the first an order to the Red Army to attack the Makhnovists,

the second ordering Makhno's assassination. Soon after the Fourth

Congress, Trotsky sent an order to arrest every Nabat congress

member. Pursued by White Army forces, Makhno and the Black Army

responded by withdrawing further into the interior of Ukraine. In 1919,

the Black Army suddenly turned eastwards in a full scale offensive,

surprising General Denikin's White forces and causing them to fall back.

Within two weeks, Makhno and the Black Army had recaptured all of the

southern Ukraine.

When nearly half of Makhno's troops were struck by a typhus epidemic, Trotsky resumed hostilities; the Cheka sent two agents to assassinate Makhno in 1920, but were captured and after confessing, were executed. All through February, 1920 the Free Territory - Makhnovist region - was inundated with Red troops, including the 42nd Rifle Division and the Latvian & Estonian Division – in total at least 20,000 soldiers. Viktor Belash noted that even in the worst time for the revolutionary army, namely at the beginning of 1920, "In the majority of cases rank - and - file Red Army soldiers were set free". Of course Belash, as a colleague of Makhno's, was likely to idealize the punishment policies of the Batko. However, the facts bear witness that Makhno really did release "in all four directions" captured Red Army soldiers. This is what happened at the beginning of February 1920, when the insurgents disarmed the 10,000 strong Estonian Division in Huliaipole. To this it must be added that the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine included a choir of Estonian musicians. The problem was further compounded by the alienation of the Estonians by Anton Denikin's inflexible Russian chauvinism and their refusal to fight with Nikolai Yudenich.

There was a new truce between Makhnovist forces and the Red Army in October 1920 in the face of a new advance by Wrangel's White army. While Makhno and the anarchists were willing to assist in ejecting Wrangel and White Army troops from southern Ukraine and Crimea, they distrusted the Bolshevist government in Moscow and its motives. However, after the Bolshevik government agreed to a pardon of all anarchist prisoners throughout Russia, a formal treaty of alliance was signed.

By late 1920, Makhno had successfully halted General Wrangel's White Army advance into Ukraine from the southwest, capturing 4,000 prisoners and stores of munitions, and preventing the White Army from gaining control of the all important Ukrainian grain harvest. Eventually, after shifting forces from the Polish - Soviet campaign, Red Army units also participated in the southern campaign that pursued Wrangel and the remainder of his forces down the Crimean peninsula. To the end, Makhno and the anarchists maintained their main political structures, refusing demands to join the Red Army, to hold Bolshevik supervised elections, or accept Bolshevik appointed political commissars. The Red Army temporarily accepted these conditions, but within a few days ceased to provide the Makhnovists with basic supplies, such as cereals and coal.

When General Wrangel's White Army forces were decisively defeated in

November 1920, the Communists immediately turned on Makhno and the

anarchists once again. After refusing a direct order by the Bolshevik

government to disband his anarchist army, Makhno intercepted three

messages from Lenin to Christian Rakovsky,

the head of the Bolshevik Ukrainian Soviet based in Kharkiv. Lenin's

orders were to arrest all members of Makhno's organization and to try

them as common criminals. On November 26, 1920, less than two weeks

after assisting Red Army forces to defeat Wrangel, Makhno's headquarters

staff and many of his subordinate commanders were arrested at a Red

Army planning conference to which they had been invited by Moscow, and

executed. Makhno escaped, but was soon forced into retreat as the full

weight of the Red Army and the Cheka's Special Punitive Brigades was brought to bear against not only the Makhnovists, but all anarchists, even their admirers and sympathizers.

In August 1921, an exhausted Makhno was finally driven by Mikhail Frunze's Ukrainian Red forces into exile with the remainder of his anarchist army, fleeing to Romania, then Poland, Danzig, Berlin and finally to Paris. In 1926, he joined other Russian exiles in Paris as part of the Group of Russian Anarchists Abroad (Группа Русских Анархистов Заграницей) who produced the monthly journal "Dielo Truda" (Дело Труда, The Cause of Labor). Makhno co-wrote and co-published the Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists (often referred to as the Organizational Platform of the Libertarian Communists), which put forward ideas on how anarchists should organize, based on the experiences of revolutionary Ukraine and the defeat by the Bolsheviks. The document was initially rejected by many anarchists, but today has a wide following. It remains controversial to this day, continuing to inspire some anarchists (notably the platformism tendency) because of the clarity and functionality of the structures it proposes, while drawing criticism from others (including, at the time of publication, Voline and Malatesta) who viewed its implications as too rigid and hierarchical.

At the end of his life Makhno lived in Paris and worked as a carpenter

and stage hand at the Paris Opera, at film studios, and at the Renault

factory. He died in Paris on July 6, 1934, from tuberculosis. He was

cremated three days after his death, with five hundred people attending

his funeral at the famous cimetière du Père - Lachaise

in Paris. Makhno's widow and his daughter Yelena, were deported to

Germany for forced labor during World War II. After the end of the war

they were arrested by the NKVD. They were taken to Kiev for trial in

1946 and sentenced to eight years of hard labor. They lived in

Kazakhstan after their release in 1953.

In 1919, Nestor Makhno married Agafya (aka Halyna) Kuzmenko, a former elementary schoolteacher (1892 – 1978), who became his aide. They had one daughter, Yelena. Halyna Kuzmenko personally carried out a death sentence of ataman Nikifor Grigoriev, a subordinate commander who committed a series of anti - semitic pogroms (according to other accounts, Grigoriev was killed by Chubenko, a member of Makhno's staff or Makhno himself).

Two of Makhno's brothers were his active supporters and aides before being captured in battle by the German occupation forces and executed by firing squad.

According to Paul Avrich, Makhno was a thoroughgoing anarchist and down - to - earth peasant. He rejected metaphysical systems and abstract social theorizing.

Voline, one of his biggest supporters who was active for several

months in the movement, reports that Makhno and his associates engaged

in sexual mistreatment of women: "Makhno and of many of his intimates --

both commanders and others... let themselves indulge in shameful and

even odious activities, going as far as orgies in which certain women

were forced to participate."

However, Voline's allegations against Makhno in regards to sexual

violations of women has been disputed by some on the grounds that the

allegations are unsubstantiated, do not stand up to eyewitness accounts

of the punishment meted out to rapists by the Makhnovists, and were

originally made by Voline in his book The Unknown Revolution which was first published in 1947, long after Makhno's death and following a bitter falling out between Makhno and Voline. It has also been pointed out by A. Skirda

that Makhno's wife often traveled alongside Makhno during the war years

in Ukraine and that she, and other armed insurgent women who were

members of the Makhnovists movement, would not likely have tolerated

such infidelities and abuse towards women on the part of her husband or

other male insurgents.

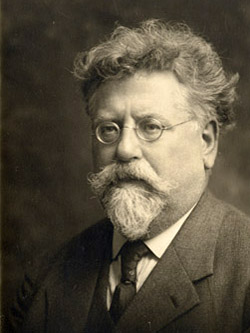

Johann Rudolf Rocker (March 25, 1873 – September 19, 1958) was an anarcho - syndicalist writer and activist. A self professed anarchist without adjectives, Rocker believed that anarchist schools of thought represented "only different methods of economy" and that the first objective for anarchists was "to secure the personal and social freedom of men".

Rudolf Rocker was born to the lithographer Georg Philipp Rocker and his wife Anna Margaretha née Naumann as the second of three sons in Mainz, Hesse (now Rhineland - Palatinate), Germany on March 25, 1873. This Catholic, yet not particularly devout, family had a democratic and anti - Prussian tradition dating back to Rocker's grandfather, who participated in the March Revolution of 1848. However, Georg Philipp died just four years after Rocker's birth. After that, the family managed to evade poverty, only through the massive support by his mother's family. Rocker's uncle and godfather Carl Rudolf Naumann, a long - time member of the Social Democratic Party (SPD), became a substitute for his dead parents and a role model, who directed the boy's intellectual development. Rocker was disgusted by his schoolteacher's authoritarian methods calling the man a "heartless despot". He was, therefore, a poor student. When he was ten, the Rocker household was joined by his mother's new husband Ludwig Baumgartner. Rocker was shocked once again as his mother died in February 1877. After his stepfather re-married soon thereafter, Rocker was put into an orphanage.

Disgusted by the unconditional obedience demanded by the Catholic

orphanage and drawn by the prospect of adventure, Rocker ran away from

the orphanage twice. The first time he just wandered around in the woods

around Mainz with occasional visits to the city to forage for food and

was retrieved after three nights. The second time, which was at the age

of fourteen and a reaction to the orphanage wanting him to be

apprenticed as a tinsmith,

he worked as a cabin boy for Köln - Düsseldorfer

Dampfschiffahrtsgesellschaft. He enjoyed leaving his hometown and

traveling to places like Rotterdam. After he returned, he started an

apprenticeship to become a typographer like his uncle Carl.

Political rights do not originate in parliaments; they are, rather, forced upon parliaments from without. And even their enactment into law has for a long time been no guarantee of their security. Just as the employers always try to nullify every concession they had made to labor as soon as opportunity offered, as soon as any signs of weakness were observable in the workers' organizations, so governments also are always inclined to restrict or to abrogate completely rights and freedoms that have been achieved if they imagine that the people will put up no resistance. Even in those countries where such things as freedom of the press, right of assembly, right of combination, and the like have long existed, governments are constantly trying to restrict those rights or to reinterpret them by juridical hair - splitting. Political rights do not exist because they have been legally set down on a piece of paper, but only when they have become the ingrown habit of a people, and when any attempt to impair them will meet with the violent resistance of the populace . Where this is not the case, there is no help in any parliamentary Opposition or any Platonic appeals to the constitution.

— Rudolf Rocker, Anarcho - Syndicalism: Theory & Practice, 1947

Carl also had a substantial library consisting of socialist literature of all colors. Rocker was particularly impressed by the writings of Constantin Franz, a federalist and opponent of Bismarck's centralized German Empire; Eugen Dühring, an anti - Marxist socialist, whose theories had some anarchist aspects; novels like Victor Hugo's Les Misérables and Edward Bellamy's Looking Backward; as well as the traditional socialist literature such as Karl Marx's Capital and Ferdinand Lasalle and August Bebel's writings. Although Rocker is unlikely to have grasped all of the political and philosophical implications of what he read, he became a socialist and regularly discussed his ideas with others. His employer became the first person he converted to socialism.

Under the influence of his uncle, he joined the SPD and became active in the typographers' labor union in Mainz. He volunteered in the 1890 electoral campaign, which had to be organized in semi - clandestinity because of continuing government repression, helping the SPD candidate Franz Jöst retake the seat for the district Mainz - Oppenheim in the Reichstag. Because the seat was heavily contested, important SPD figures like August Bebel, Wilhelm Liebknecht, Georg von Vollmar, and Paul Singer visited the town to help Jöst and Rocker had a chance to see them speak.

In 1890, there was a major debate in the SPD about the tactics

it would choose after the lifting of the Anti - Socialist Laws. A

radical oppositional wing known as Die Jungen (The Young Ones) developed. While the party leaders viewed the parliament as a means of social change, Die Jungen

thought it could at best be used to spread the socialist message. They

were unwilling to wait for the collapse of capitalist society, as

predicted by Marxism, rather they wanted to start a revolution as soon

as possible. Although this wing was strongest in Berlin, Magdeburg, and

Dresden, it also had a few adherents in Mainz, among them Rudolf Rocker.

In May 1890, he started a reading circle, named Freiheit (Freedom),

to study theoretical topics more intensively. After Rocker criticized

Jöst and refused to retract his statements, he was expelled from the

party. The same would happen to the rest of Die Jungen in October

1891. Nonetheless, he remained active and even gained influence in the

socialist labor movement in Mainz. Although he had already encountered

anarchist ideas as a result of his contacts to Die Jungen in Berlin, his conversion to anarchism did not take place until the International Socialist Congress in Brussels

in August 1891. He was heavily disappointed by the discussions at the

congress, as it, especially the German delegates, refused to explicitly

denounce militarism. He was rather impressed by the Dutch socialist and later anarchist Domela Nieuwenhuis,

who attacked Liebknecht for his lack of militancy. Rocker got to know

Karl Höfer, a German active in smuggling anarchist literature from Belgium to Germany. Höfer gave him Bakunin's God and the State and Kropotkin's Anarchist Morality, two of the most influential anarchist works, as well as the newspaper Autonomie.

Rocker became convinced that the source of political institutions is an irrational belief in a higher authority, as Bakunin claimed in God and the State. However, Rocker rejected the Russian's rejection of theoretical propaganda and his claim that only revolutions can bring about change. Nevertheless, he was very much attracted by Bakunin's style, marked by pathos, emotion, and enthusiasm, designed to give the reader an impression of the heat of revolutionary moments. Rocker even attempted to emulate this style in his speeches, but was not very convincing. Kropotkin's anarcho - communist writings, on the other hand, were structured logically and contained an elaborate description of the future anarchist society. The work's basic premise, that an individual is entitled to receive the basic means of living from the community independently of his or her personal contributions, impressed Rocker.

In 1891, all Die Jungen were either expelled from the SPD or left voluntarily. They then founded the Union of Independent Socialists (VUS). Rocker became a member and founded a local section in Mainz, mostly active in distributing anarchist literature smuggled in from Belgium or the Netherlands in the city. He was a regular speaker at labor union meetings. On December 18, 1892, he spoke at a meeting of unemployed workers. Impressed by Rocker's speech, the speaker that followed Rocker, who was not from Mainz and therefore did not know at what point the police would intervene, advised the unemployed to take from the rich, rather than starve. The meeting was then dissolved by the police. The speaker was arrested, while Rocker barely escaped. He decided to flee Germany to Paris via Frankfurt. He had, however, already been toying with the idea of leaving the country, in order to learn new languages, get to know anarchist groups abroad, and, above all, to escape conscription.

In Paris, he first came into contact with Jewish anarchism.

In Spring 1893, he was invited to meeting of Jewish anarchists, which

he attended and was impressed by. Though neither a Jew by birth nor by

belief, he ended up frequenting the group's meeting, eventually holding

lectures himself. Solomon Rappaport, later known as S. Ansky,

allowed Rocker to live with him, as they were both typographers and

could share Rappaport's tools. During this period, Rocker also first

came into contact with the blending of anarchist and syndicalist ideas represented by the General Confederation of Labor

(CGT), which would influence him in the long term. In 1895, as a result

of the anti - anarchist sentiment in France, Rocker traveled to London to

visit the German consulate and examine the possibility of his returning

to Germany but was told he would be imprisoned upon return.

Rocker decided to stay in London. He got a job as the librarian of the Communist Workers' Educational Union, where he got to know Louise Michel and Errico Malatesta, two influential anarchists. Inspired to visit the quarter after reading about "Darkest London" in the works of John Henry Mackay, he was appalled by the poverty he witnessed in the predominantly Jewish East End. He joined the Jewish anarchist Arbeter Fraint group he had obtained information about from his French comrades, quickly becoming a regular lecturer at its meetings. There, he met his lifelong companion Milly Witkop, a Ukrainian born Jew who had fled to London in 1894. In May 1897, having lost his job and with little chance of re-employment, Rocker was persuaded by a friend to move to New York. Witkop agreed to accompany him and they arrived on the 29th. They were, however, not admitted into the country, because they were not legally married. They refused to formalize their relationship. Rocker explained that their "bond is one of free agreement between my wife and myself. It is a purely private matter that only concerns ourselves, and it needs no confirmation from the law." Witkop added: "Love is always free. When love ceases to be free it is prostitution." The matter received front page coverage in the national press. The Commissioner General of Immigration, the former Knights of Labor President Terence V. Powderly, advised the couple to get married to settle the matter, but they refused and were deported back to England on the same ship they had arrived on.

Unable to find employment upon return, Rocker decided to move to Liverpool. A former Whitechapel comrade of his persuaded him to become the editor of a recently founded Yiddish weekly newspaper called Dos Fraye Vort (The Free Word), even though he did not speak the language at the time. The newspaper only appeared for eight issues, but it led the Arbeter Fraint group to re-launch its eponymous newspaper and invite Rocker to return to the capital and take over as its editor.

Although it received some funds from Jews in New York, the journal's financial survival was precarious from the start. However, many volunteers helped by selling the paper on street corners and in workshops. During this time, Rocker was especially concerned with combating the influence of Marxism and historical materialism in London's Jewish labor movement. In all, the Arbeter Fraint published twenty - five essays by Rocker on the topic, the first ever critical examination of Marxism in Yiddish, according to William J. Fishman. Arbeter Fraint's unsound financial footing also meant Rocker rarely received the small salary promised to him when he took over the journal and he depended financially on Witkop. Despite Rocker's sacrifices, however, the paper was forced to cease publication for lack of funds. In November 1899, the prominent American anarchist Emma Goldman visited London and Rocker met her for the first time. After hearing of the Arbeter Fraint's situation she held three lectures to raise funds, but that was not enough.

Not wanting to be left without any means of propaganda, Rocker founded the Germinal in March 1900. Compared to Arbeter Fraint,

it was more theoretical, applying anarchist thought to the analysis of

literature and philosophy. It represented a maturation of Rocker's

thinking towards Kropotkin-ite

anarchism and would survive until March 1903. 1902 saw the London Jews

being targeted by a wave of anti - alien sentiment, while Rocker was

away for a year in Leeds. Upon return in September, he was happy to see

the Jewish anarchists had kept the Arbeter Fraint organization alive. A conference of all Jewish anarchists of the city on December 26 decided for a re-launch of the Arbeter Fraint

newspaper as the organ of all Jewish anarchists in Great Britain and

Paris and made Rocker the editor. The first issue appeared on March 20,

1903. Following the Kishinev pogrom in the Russian Empire,

Rocker led a demonstration in solidarity with the victims, the largest

ever gathering of Jews in London. Afterwards he traveled to Leeds, Glasgow, and Edinburgh to lecture on the topic.

From 1904, the Jewish labor and anarchist movements in London reached their "golden years", according to William J. Fishman. In 1905, publication of Germinal resumed, it reached a circulation of 2,500 a year later, while Arbeter Fraint reached a demand of 5,000 copies. In 1906, the Arbeter Fraint group finally realized a long time goal, the establishment of a club for both Jewish and gentile workers. The Workers' Friend Club was founded in a former Methodist church on Jubilee Street. Rocker, by now a very eloquent speaker, became a regular speaker. As a result of the popularity of both the club and Germinal beyond the anarchist scene, Rocker befriended many prominent non - anarchist Jews in London, among them the Zionist philosopher Ber Borochov.

From June 8, 1906, Rocker was involved in a garment workers' strike.

Wages and working conditions in the East End were much lower than in the

rest of London and tailoring was the most important industry. Rocker

was asked by the union leading the strike to become part of the strike

committee along with two other Arbeter Fraint members. He was a

regular speaker at the strikers' gatherings. The strike failed, because

the strike funds ran out. By July 1, all workers were back in their workshops.

Rocker represented the federation at the International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam in 1907. Errico Malatesta, Alexander Shapiro, and he became the secretaries of the new Anarchist International, but it only lasted until 1911. Also in 1907, his son Fermin was born. In 1909, while visiting France, Rocker denounced the execution of the anarchist pedagogue Francisco Ferrer in Barcelona, leading him to be deported back to England.

In 1912, Rocker was once again an important figure in a strike by

London's garment makers. In late April, 1,500 tailors from the West End,

who were more highly skilled and better paid than those in the East

End, started striking. By May, the total number was between 7,000 and

8,000. Since much of the West Enders' work was now being performed in

the East End, the tailors' union there, under the influence of the Arbeter Fraint

group, decided to support the strike. Rudolf Rocker on the one hand saw

this as a chance for the East End tailors to attack the sweatshop

system, but on the other was afraid of an anti - Semitic backlash, should

the Jewish workers remain idle. He called for a general strike.

His call was not followed, since over seventy percent of the East End

tailors were engaged in the ready made trade, which was not linked with

the West End workers' strike. Nonetheless, 13,000 immigrant garment

workers from the East End went on strike following a May 8 assembly at

which Rocker spoke. Not one worker voted against a strike. Rocker became

a member of the strike committee and chairman of the finance

sub-committee. He was responsible for collecting money and other

necessities for the striking workers. On the side he published the Arbeter Fraint

newspaper on a daily basis to disseminate news about the strike. He

also

spoke at the workers' assemblies and demonstrations. On May 24 a mass

meeting was held to discuss the question of whether to settle on a

compromise proposed by the employers, which did not entail a closed

union shop. A speech by Rocker convinced the workers to continue the

strike. By the next morning, all of the workers' demands were met.

Rocker opposed both sides in World War I on internationalist grounds. Although most in the United Kingdom and continental Europe expected a short war, Rocker predicted on August 7, 1914 "a period of mass murder such as the world has never known before" and attacked the Second International for not opposing the conflict. Rocker with some other Arbeter Fraint members opened up a soup kitchen without fixed prices to alleviate the further impoverishment that came with the Great War. There was a debate between Kropotkin, who supported the Allies, and Rocker in Arbeter Fraint in October and November. He called the war "the contradiction of everything we had fought for".

Shortly after the publication of this statement, on December 2,

Rocker was arrested and interned as an enemy alien. This was also the

result of the anti - German sentiment in the country. Arbeter Fraint was suppressed in 1915. The Jewish anarchist movement in Britain never fully recovered from these blows.

In March 1918, Rocker was taken to the Netherlands under an agreement to exchange prisoners through the Red Cross. He stayed at the house of the socialist leader Domela Nieuwenhuis and he recovered from the health problems from which he suffered as a result of his internment in the UK and met up with his wife Milly Witkop and his son Fermin. He returned to Germany in November 1918 upon an invitation from Fritz Kater to join him in Berlin to re-build the Free Association of German Trade Unions (FVdG). The FVdG was a radical labor federation that quit the SPD in 1908 and became increasingly syndicalist and anarchist. During World War I, it had been unable to continue its activities for fear of government repression, but remained in existence as an underground organization.

Rocker was opposed to the FVdG's alliance with the communists during and immediately after the November Revolution, as he rejected Marxism, especially the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Soon after arriving in Germany, however, he once again became seriously ill. He started giving public speeches in March 1919, including one at a congress of munitions workers in Erfurt, where he urged them to stop producing war material. During this period the FVdG grew rapidly and the coalition with the communists soon began to crumble. Eventually all syndicalist members of the Communist Party were expelled. From December 27 to December 30, 1919, the twelfth national congress of the FVdG was held in Berlin.

The organization decided to become the Free Workers' Union of Germany

(FAUD) under a new platform, which had been written by Rocker: the Prinzipienerklärung des Syndikalismus (Declaration of Syndicalist Principles).

It rejected political parties and the dictatorship of the proletariat

as bourgeois concepts. The program recognized only decentralized, purely

economic, organizations. Although public ownership of land, means of

production, and raw materials was advocated, nationalization and the

idea of a communist state were rejected. Rocker decried nationalism as

the religion of the modern state and opposed violence, championing

instead direct action and the education of the workers.

On Gustav Landauer's death during the Munich Soviet Republic uprising, Rocker took over the work of editing the German publications of Kropotkin's writings. In 1920, the social democratic Defense Minister Gustav Noske started the suppression of the revolutionary left, which led to the imprisonment of Rocker and Fritz Kater. During their mutual detainment, Rocker convinced Kater, who had still held some social democratic ideals, completely of anarchism.

In the following years, Rocker became one of the most regular writers in the FAUD organ Der Syndikalist. In 1920, the FAUD hosted an international syndicalist conference, which ultimately led to the founding of the International Workers Association

(IWA) in December 1922. Augustin Souchy, Alexander Schapiro, and Rocker

became the organization's secretaries and Rocker wrote its platform. In

1921, he wrote the pamphlet Der Bankrott des russischen Staatskommunismus (The Bankruptcy of Russian State Communism)

attacking the Soviet Union. He denounced what he considered a massive

oppression of individual freedoms and the suppression of anarchists

starting with the a purge on April 12, 1918. He supported instead the

workers who took part in the Kronstadt uprising

and the peasant movement led by the anarchist Nestor Makhno, whom he

would meet in Berlin in 1923. In 1924, Rocker published a biography of

Johann Most called Das Leben eines Rebellen (The Life of a Rebel).

There are great similarities between the men's vitas. It was Rocker who

convinced the anarchist historian Max Nettlau to start publication of

his anthology Geschichte der Anarchie (History of Anarchy) in 1925.

During the mid 1920s, the decline of Germany's syndicalist movement started. The FAUD had reached its peak of around 150,000 members in 1921, but then started losing members to both the Communist and the Social Democratic Party. Rocker attributed this loss of membership to the mentality of German workers accustomed to military discipline, accusing the communists of using similar tactics to the Nazis and thus attracting such workers. At first only planning a short book on nationalism, he started work on Nationalism and Culture, which would be published in 1937 and become one of Rocker's best known works, around 1925. 1925 also saw Rocker visit North America on a lecture tour with a total of 162 appearances. He was encouraged by the anarcho - syndicalist movement he found in the US and Canada.

Returning to Germany in May 1926, he became increasingly worried

about the rise of nationalism and fascism. He wrote to Nettlau in 1927:

"Every nationalism begins with a Mazzini, but in its shadow there lurks a Mussolini". In 1929, Rocker was a co-founder of the Gilde freiheitlicher Bücherfreunde

(Guild of Libertarian Bibliophiles), a publishing house which would

release works by Alexander Berkman, William Godwin, Erich Mühsam, and

John Henry Mackay.

In the same year he went on a lecture tour in Scandinavia and was

impressed by the anarcho - syndicalists there. Upon return, he wondered

whether Germans were even capable of anarchist thought. In the 1930 elections,

the Nazi Party received 18.3% of all votes, a total of 6 million.

Rocker was worried: "Once the Nazis get to power, we'll all go the way

of Landauer and Eisner" (who were killed by reactionaries in the course

of the Munich Soviet Republic uprising).

In 1931, Rocker attended the IWA congress in Madrid and then the unveiling of the Nieuwenhuis memorial in Amsterdam. In 1933, the Nazis came to power. After the Reichstag fire on February 27, Rocker and Witkop decided to leave Germany. As they left they received news of Erich Mühsam's arrest. After his death in July 1934, Rocker would write a pamphlet called Der Leidensweg Erich Mühsams (The Life and Suffering of Erich Mühsam) about the anarchist's fate. Rocker reached Basel, Switzerland, on March 8 by the last train to cross the border without being searched. Two weeks later, Rocker and his wife joined Emma Goldman in St. Tropez, France. There he wrote Der Weg ins Dritte Reich (The Path to the Third Reich) about the events in Germany, but it would only be published in Spanish.

In May, Rocker and Witkop moved back to London. There Rocker was welcomed by many of the Jewish anarchists he had lived and fought alongside for many years. He held lectures all over the city. In July, he attended an extraordinary IWA meeting in Paris, which decided to smuggle its organ Die Internationale into Nazi Germany.

On August 27, Rocker with his wife emigrated to New York. There they

were reunited with Fermin who had stayed there after accompanying his

father on his 1929 lecture tour in the US. The Rocker family moved to

live with a sister of Witkop's in Towanda, Pennsylvania,

where many families with progressive or libertarian socialist views

lived. In October, Rocker toured the US and Canada speaking about

racism, fascism, dictatorship, socialism in English, Yiddish, and

German. He found many of his Jewish comrades from London, who had since

emigrated to America, and became a regular writer for Freie Arbeiter Stimme,

a Jewish anarchist newspaper. Back in Towanda in the Summer of 1934,

Rocker started work on an autobiography, but news of Erich Mühsam's

death led him to halt his work. He was working on Nationalism and Culture, when the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936 instilling great optimism in Rocker. He published a pamphlet The Truth about Spain and contributed to The Spanish Revolution, a special fortnightly newspaper published by American anarchists to report on the events in Spain. In 1937, he wrote The Tragedy of Spain,

which analyzed the events in greater detail. In September 1937, Rocker

and Witkop moved to the libertarian commune Mohegan Colony about 50

miles (80 km) from New York City.

In 1937, Nationalism and Culture, which he had started work on around 1925, was finally published with the help of anarchists from Chicago Rocker had met in 1933. A Spanish edition was released in three volumes in Barcelona, the stronghold of the Spanish anarchists. It would be his best known work. In the book, Rocker traces the origins of the state back to religion claiming "that all politics is in the last instance religion": both enslave their very creator, man; both claim to be the source of cultural progress. He aims to prove the claim that culture and power are essentially antagonistic concepts. He applies this model to human history, analyzing the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, Enlightenment, and modern capitalist society, and to the history of the socialist movement. He concludes by advocating a "new humanitarian socialism".

In 1938, Rocker published a history of anarchist thought, which he traced all the way back to ancient times, under the name Anarcho - Syndicalism. A modified version of the essay would be published in the Philosophical Library series European Ideologies under the name Anarchism and Anarcho - Syndicalism in 1949.

In 1939, Rocker had to undergo a serious operation and was forced to give up lecture tours. However, in the same year, the Rocker Publications Committee was formed by anarchists in Los Angeles to translate and publish Rockers writings. Many of his friends died around this time: Alexander Berkman in 1936, Emma Goldman in 1940, Max Nettlau in 1944; many more were imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps. Although Rocker had opposed his teacher Kropotkin for his support of the Allies during World War I, Rocker argued that the Allied effort in World War II was just, as it would ultimately lead to preservation of libertarian values. Although he viewed every state as a coercive apparatus designed to secure the economic exploitation of the masses, he defended democratic freedoms, which he considered a result of a desire for freedom of the enlightened public. This position was criticized by many American anarchists, who did not support any war.

After World War II, an appeal in the Fraye Arbeter Shtime detailing the plight of German anarchists and called for Americans to support them. By February 1946, the sending of aid parcels to anarchists in Germany was a large scale operation. In 1947, Rocker published Zur Betrachtung der Lage in Deutschland (Regarding the Portrayal of the Situation in Germany) about the impossibility of another anarchist movement in Germany. It became the first post World War II anarchist writing to be distributed in Germany. Rocker thought young Germans were all either totally cynical or inclined to fascism and awaited a new generation to grow up before anarchism could bloom once again in the country. Nevertheless, the Federation of Libertarian Socialists (FFS) was founded in 1947 by former FAUD members. Rocker wrote for its organ, Die Freie Gesellschaft, which survived until 1953. In 1949, Rocker published another well known work. In Pioneers of American Freedom, a series of essays, he details the history of liberal and anarchist thought in the United States, seeking to debunk the idea that radical thought was foreign to American history and culture and had merely been imported by immigrants. On his eightieth birthday in 1953, a dinner was held in London to honor Rocker. Messages of gratitude were read by the likes of Thomas Mann, Albert Einstein, Herbert Read, and Bertrand Russell.

On September 10, 1958, Rocker died in the Mohegan Colony.