<Back to Index>

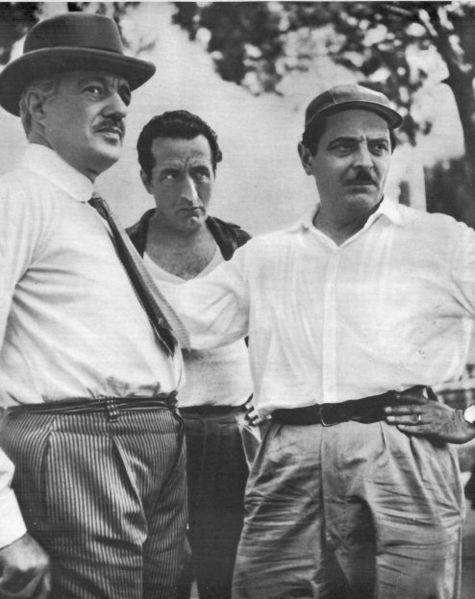

- Director Alessandro Blasetti, 1900

PAGE SPONSOR

Alessandro Blasetti (Rome, 3 July 1900 - Rome, February 1, 1987) was an Italian director, writer, editor and actor, the most famous and significant of his time, so it can be defined as "the founding father of modern Italian cinema".

It is considered, along with Mario Camerini, the most famous Italian director of Fascist cinema, who was also, in some cases, an apologist: the Sun (1929), his film debut, is an epic exaltation of the reclamation scheme and pleased Benito Mussolini; Old Guard (1935) is an apology for the march on Rome.

During the five decades of his active work, he was successful in many different genres, from historical to the heroic to the romantic comedy, literally inventing new ones (fantasy with the Iron Crown of 1941, the episodic film with Other Periods of 1952 , romantic documentary with Europe in the Night of 1958), and was among the first filmmakers to experiment with television.

He was a great technical innovator, pioneering the sound in Italy (Resurrection of 1930) and the color (Fox Hunting in the Roman Countryside of 1938), has tested the limits of what was permissible to show on large screen, offering the first nudity in Italian film (The Iron Crown and Dinner of the Tricks of 1941), has launched new authors such as Pietro Germi and introduced Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni (Pity She's a Rogue's 1954).

Son of Cesare, professor of oboe and English horn at ' Accademia di Santa Cecilia, and Augusta Luliani, Alessandro Blasetti studied at fathers Somascans Rosi to the College of Spello, attended high school at the Military College in Rome and completed his university studies in law the University of Rome, following the tradition of his maternal family. He married in 1923, working as a bank clerk and graduated in 1924, but in the meantime he devoted himself to journalism and worked as a film critic.

Since 1923 he wrote for The Empire, on which in 1925 opened the first film column in a newspaper, called The Screen. In early 1926 he founded with Renzo Cesana The world and the screen , "illustrated weekly cinema", that was renamed The Shield a few months later, all of which lasted for 22 issues. In March 1927 he founded the cinema, published up to July 1931, and supported The Spectacle of Italy, published from October 1927 to June 1928. At the cinema, which gathered the personalities involved in the "renaissance" of Italian cinema, including intellectuals such as Anton Giulio Bragaglia and Massimo Bontempelli, cinema was considered in all aspects (financial, industrial, technical, political, critical, aesthetic), in an organic project that aspired to merge theory and practice. As a result, it was natural for Blasetti the transition to film practice.

At the end of 1928, he founded the cooperative, which made his film debut, the Sun, on the issue of land reclamation, in line with the rural policies of the fascist regime, which was a commercial failure, a premature failure of this independent production experience.

Blasetti then accepted the call by Stefano Pittaluga, the founder of Cines, although in the recent past Pittaluga had been heavily criticized in the pages of Cinema for "industrial, artistic, political or commercial incompetence', having to recognize that, his was the single project with the potential to raise production in Italian cinema. The first film produced by the new Cines, written and directed by Blasetti, was the pioneering Resurrectio (1930), the first Italian sound film, even though it was distributed after the next The love song of Renato Rulers, due to commercial considerations. This was a new failure, but the director had a particularly important opportunity to explore the possibilities of sound in all its forms (music, noise, dialogue).

Alessandro then employed the services of Hector Petrolini for the movie Nero (1930), focused entirely on the protagonist. This was not a pure movie, because Blasetti, while only calling himself "technical coordinator", made his presence felt staging the theater itself, including the audience, and leaving his mark in the choice of shots and the camera movements, including the original carriage drawn from the production which was technically very challenging at that time.

The next film, Mother Earth (1931), tackled the theme of "return to earth", suggesting a history built on the opposition of corrupt city life and healthy rural life, and the functional ruralista policy of the regime, which enjoyed the support of the government. Despite the lukewarm critical reception, the film was a big success. A similar approach was followed in the strongly populist Palio (1931),exposing the contrast between aristocrats and commoners, a film with a weak narrative structure, which was remarkable for the figurative and formal aspects presented by the physical environment at Siena.

Pittaluga died in 1931, and the general direction of the production was assumed by Cines writer Emilio Cecchi , who established a very profitable relationship with Blasetti. During his tenure, Blasetti directed the short film Assisi (1932), The table of the poor (1932), based on the play by Raffaele Viviani, the remakes of the successful foreign films Haller's case (1933) and the clerk Dad (1934), and especially what is almost unanimously considered his masterpiece, 1860 (1934), on the Expedition of the Thousand. The film, later recognized as one of the forerunners of neorealism, was received favorably by critics, snubbed by the public, little interested in the issue of the Risorgimento, and was not much appreciated by the regime, because it was little celebratory, although, despite not being crudely propagandistic, was in many respects in perfect harmony with the official policy of the fascists.

Also in 1934, the fateful year for Italian cinema for the fortunate confluence of several major titles and the establishment of the Directorate General of cinematography, Blasetti reached the pinnacle of his political commitment and his involvement with the fascist regime, with two celebrations of Fascist Italy, the movie Old Guard and the play 18 BL. The first has much in common with the previous 1860, including the failure in the public, despite the appreciation by Mussolini; the latter was presented only once, in Florence.

From here on in the film, he embarked on a path of gradual disengagement from the larger social issues and scaling of the political value of his films. After a couple of minor works, Aldebaran (1935) and Countess of Parma (1937), the next period

of pure escapism was initiated, with the adventure of Salvator Rosa (1939), The Iron Crown (1941) and Dinner of the tricks (1941), which were acclaimed from both critics and audiences.

Compared to these films, A walk in the clouds (1942), a fictional rural idyll by the subdued tones and dark pessimism, marked a radical change, that was deliberately sought by Blasetti, who accepted its direction only after the failure of some projects in line with his earlier works (of Francesca da Rimini, on the Sicilian Vespers, the daughter of Iorio of Gabriele D'Annunzio, Harlem, on Italian emigration, then directed by Gallon), but reflected the spirit of the times. Along with Obsession of Luchino Visconti and The Children Are Watching of Vittorio De Sica, this film was not so much a preview of neo-realism , as a break with the Italian cinema of the preceding decade.

The last work before Blasetti Liberation was the women's psychological drama Nobody comes back, from the novel of Alba de Céspedes, which brought together the major Italian actresses of the time. Filmed in 1943, in the midst of conflict (bombings hit Rome not far from the factories where filming was taking place), it was distributed only in 1945, without success.

After September 8, Blasetti did not support the Republic of Salo, and after the war, a line of general amnesty prevailed, but he could not return to work, as almost all directors that had compromised with the fascist regime, but played a major role in the aesthetic debate, on the political or economic impact on Italian cinema, introducing himself as a man of mediation and cooperation and defending national production against the encroachments of American cinema.

In the second half of the forties he worked through Salvo D'Angelo, with two Catholic manufacturers, the Orbis, which produced A Day in the Life (1945), and Universalia, which produced Fabiola (1949), First Communion (1950) and some shorts. The religious blockbuster Fabiola, based on the novel Fabiola or the Church of the catacombs of Nicholas Wiseman, was the first major production and achieved wide success with the public (best collection of his season), but was rejected by critics and aroused the hostility of the Catholic Church, for certain sexually transgressive images.

In the fifties, he returned to Cines, proving that he still wanted to employ his experience and capability, inaugurating the diptych Other times (1952) and Our Times (1954), that achieved success in the sixties. He also contributed substantially to the emergence of national stardom: the last episode of Other times, the process of Phryne, starred the couple Vittorio De Sica - Gina Lollobrigida, then featured by Luigi Comencini in Bread, Love and Dreams (1953); the successful comedies Pity She's a rogue (1954) and Lucky to Be a Woman (1955) launched a memorable couple, reassembled together periodically over the next decades, of Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni .

With Europe at night (1958), a documentary anthology of night shows on the major European cities, Blasetti was the forerunner of a new genre of great popular success, the sexy reportage, something between eroticism and exoticism, that from Mondo Cane (1962) would also veer towards violence.

Since 1962, Blasetti was among the first filmmakers to experiment with Italian television. Given his conception of cinema as a spectacle for the masses, the passage was inevitable to a medium offering an exposure to even wider audiences. Unlike Roberto Rossellini, he devoted himself almost exclusively to documentary and film editing.

His last film Simon Bolivar is 1969 and the final work for television Venice: an exhibition was in 1981.

Old guard was released in 1934, to celebrate the twelve years since the March on Rome: Mario Cardini, in the role of Brambilla, the protagonist, was twelve years old both in film and in life. It is said that the film was not liked by Luigi Freddi, because it exalted the violence thanks to which fascism had come to power. The film also showed the strong link between fascism and bourgeois life, in contrast with the ideal of Fascist Italy, under which the support for the PNF of all social classes was highlighted. Instead it seems that Mussolini liked the film: it was said that he organized a private viewing and, in watching the film, wept. Even Adolf Hitler liked Old guard, so he invited Mario Cardini, the young protagonist, to Germany.