<Back to Index>

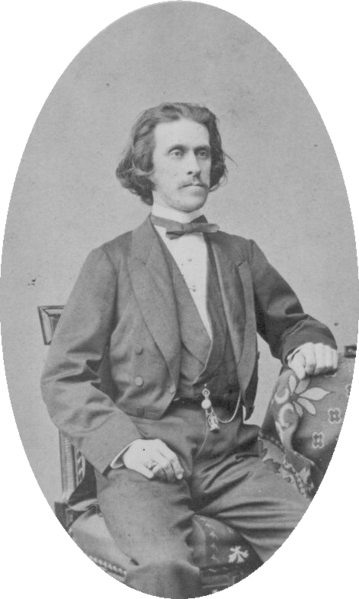

- Composer Josef Strauss, 1827

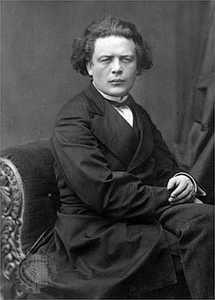

- Composer and Pianist Anton Grigorevich Rubinstein, 1829

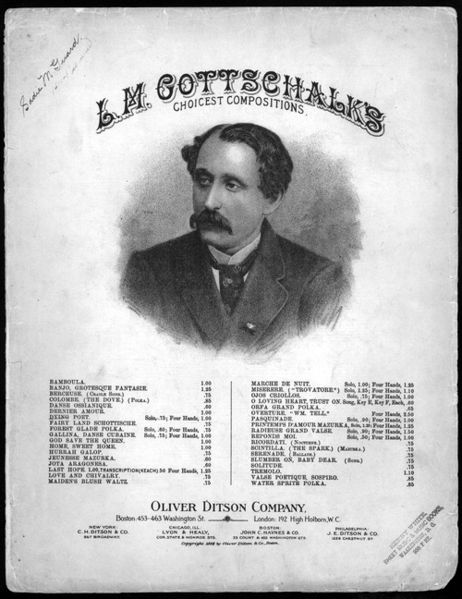

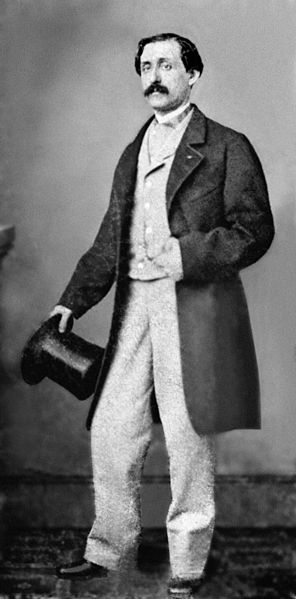

- Composer and Pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk, 1829

PAGE SPONSOR

Josef Strauss (Strauß) (August 20, 1827 – July 22, 1870) was an Austrian composer.

He was born in Vienna, the son of Johann Strauss I and Maria Anna Streim, and brother of Johann Strauss II and Eduard Strauss. His father wanted him to choose a career in the Austrian Habsburg military. He studied music with Franz Dolleschal and learned to play the violin with Franz Anton Ries.

He received training as an engineer, and worked for the city of Vienna as an engineer and designer. He designed a horse drawn revolving brush street sweeping vehicle and published two textbooks on mathematical subjects. Strauss had talents as an artist, painter, poet, dramatist, singer, composer and inventor.

He joined the family orchestra, along with his brothers, Johann Strauss II and Eduard Strauss in the 1850s. His first published work was called "Die Ersten und Letzten" (The First and the Last). When the Johann became seriously ill in 1853 Josef led the orchestra for a while. The waltz loving Viennese were appreciative of his early compositions so he decided to continue in the family tradition of composing dance music. He was known as 'Pepi' by his family and close friends, and Johann once said of him: "Pepi is the more gifted of us two; I am merely the more popular..."

Josef Strauss married Caroline Pruckmayer at the church of St. Johann Nepomuk in Vienna on 8 June 1857, and had one daughter, Karoline Anna, who was born in March 1858.

Josef Strauss wrote 283 opus numbers. He wrote many waltzes, including: Sphären - Klänge (Music of the Spheres), Delirien (Deliriums), Transaktionen (Transactions), Mein Lebenslauf ist Lieb' und Lust (My Character is Love and Joy), and Dorfschwalben aus Österreich (Village Swallows from Austria), polkas, most famously the Pizzicato Polka with his brother Johann, quadrilles, and other dance music. The waltz The Mysterious Powers of Magnetism (Dynamiden) with the use of minor keys showed a quality that distinguished his waltzes from those of his more popular elder brother. The polka - mazurka shows influence by Strauss, where he wrote many examples like Die Emancipierte and Die Libelle.

Josef Strauss was sickly most of his life. He suffered fainting spells and intense headaches. During a tour to Poland in 1870, he fell unconscious from the conductor's podium while conducting his 'Musical Potpourri'. It is not sure if he fainted and hit his head or simply became unconscious. His wife brought him back home to Vienna, to the Hirschenhaus,

where on 22 July 1870 the engineer, designer, musician, and composer

died. A final diagnosis only reported a decomposition of blood. There

were rumors that he was beaten by drunken Russian soldiers after he

allegedly refused to perform music for them one night. His cause of

death was not determined as his widow forbade an autopsy. Originally

buried in the St. Marx cemetery, Strauss was later exhumed and reburied in the Vienna Central Cemetery,

alongside his mother Anna. His dance pieces might have surpassed that

of his older brother, had he survived, as Johann was by then

concentrating on writing music for operettas and other stage works.

Anton Grigorevich Rubinstein (Russian: Анто́н Григо́рьевич Рубинште́йн) (November 28 [O.S. November 16] 1829 – November 20 [O.S. November 8] 1894) was a Russian pianist, composer and conductor. As a pianist he ranks amongst the great nineteenth century keyboard virtuosos. He founded the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, which, together with the Moscow Conservatory founded by his brother Nikolai Rubinstein, were the first music schools of their type in Russia.

Rubinstein was born to Jewish parents in the village of Vikhvatinets in the district of Podolsk, Russia, (now known as Ofatinţi in Transnistria, Republic of Moldova), on the Dniestr River, about 150 kilometers northwest of Odessa. Before he was 5 years old, his paternal grandfather ordered all members of the Rubinstein family to convert from Judaism to Russian Orthodoxy.

Rubinstein, brought up as a Christian at least in name, lived in a household where three languages were spoken — Yiddish, Russian and German. Conversion allowed the Rubinsteins to travel freely, something not permitted practicing Jews in Russia at the time. Rubinstein's father opened a pencil factory in Moscow. His mother, a competent musician, began giving him piano lessons at five. He apparently progressed rapidly. Within a year and a half, Alexander Villoing, a leading Moscow piano teacher, heard and accepted Rubinstein as a non - paying student. Rubinstein made his first public appearance, a charity benefit concert, in Moscow's Petrovsky Park at the age of nine. Later that year Rubinstein's mother sent him, accompanied by Villoing, to enroll at the Paris Conservatoire. Its Director Luigi Cherubini, however, refused an audition to Rubinstein, due to the many young prodigies who had flooded the Paris musical scene.

Rubinstein and Villoing remained in Paris for a year. In December 1840, Rubinstein played in the Salle Érard for an audience that included Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt. Chopin invited Rubinstein to his studio and played for him. Liszt acclaimed the young Rubinstein as his successor

but advised Villoing to take him to Germany to study composition.

Instead of following Liszt's advice, Villoing took Rubinstein on an

extended concert tour of Europe and Western Russia. They finally

returned to Moscow in June 1843, after an absence of three and a half

years. Shortly before the pair returned, Liszt had played in Saint

Petersburg and reiterated to Rubinstein's mother the advice which he had

given Villoing. Determined to follow Liszt's advice, she wanted a

thorough grounding in musical theory for both Rubinstein and his younger brother Nikolai.

To raise money for this, she sent Rubinstein and Villoing on a tour of

Russia. When the tour ended, the brothers were dispatched to Saint Petersburg to play for Tsar Nicholas I and the Imperial family at the Winter Palace. Anton was 14 years old; Nikolai was eight.

In spring 1844, Rubinstein, Nikolai, his mother and his sister Luba travelled to Berlin. Here he met with, and was supported by, Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer. Mendelssohn, who had heard Rubinstein when he had toured with Villoing, said he needed no further piano study but sent Nikolai to Theodor Kullak for instruction. Meyerbeer directed both boys to Siegfried Dehn for work in composition and theory. Also, a Greek Orthodox priest instructed the two boys in the catechism and Russian grammar, and both boys studied other subjects. These non - musical lessons were short lived. Still, Rubinstein grew up to be a highly cultured, widely read artist. He was fluent in Russian, German, French and English and could read Italian and Spanish literature.

Word came in the summer of 1846 that Rubinstein's father was gravely ill. Rubinstein was left in Berlin while his mother, sister and brother returned to Russia. At first he continued his studies with Dehn, then with Adolf Bernhard Marx, while composing in earnest. Now 17, he knew he could no longer pass as a child prodigy. He sought out Liszt in Vienna, hoping Liszt would accept him as a pupil.

Liszt's reaction to Rubinstein in Vienna was highly atypical of his famously generous nature. After Rubinstein had played his audition, Liszt is reported to have coldly said, "A talented man must win the goal of his ambition by his own unassisted efforts." At this point, Rubinstein was living in acute poverty. Liszt did nothing to help him. Other calls Rubinstein made to potential patrons came to no avail.

Rubinstein began giving piano lessons, continued composing, even

wrote literary, philosophical and critical essays. After a year in

Vienna he gave a concert in the Bösendörfersaal. It did not go well;

months of composition had severely reduced his time practicing the

piano. Together with a flautist he embarked on a concert tour of

Hungary, then returned to Berlin and continued giving lessons.

The Revolution of 1848 forced Rubinstein back to Russia. Spending the next five years mainly in Saint Petersburg, Rubinstein taught, gave concerts and performed frequently at the Imperial court. The Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, sister to Tsar Nicholas I, became his most devoted patroness. By 1852, he had become a leading figure in Saint Petersburg's musical life, performing as a soloist and collaborating with some of the outstanding instrumentalists and vocalists who came to the Russian capital.

He also composed assiduously. After a number of delays, including some difficulties with the censor, Rubinstein's first opera, Dmitry Donskoy

(now lost except for the overture), was performed at the Bolshoy

Theater in St. Petersburg in 1852. Three one act operas written for

Elena Pavlovna followed. He also played and conducted several of his

works, including the Ocean Symphony in its original four movement

form, his Second Piano Concerto and several solo works. It was partly

his lack of success on the Russian opera stage that led Rubinstein to

consider going abroad once more to secure his reputation as a serious

artist.

In 1854 Rubinstein began a four year concert tour of Europe. This was his first major concert tour in a decade. Now 24, he felt ready to offer himself to the public as a fully developed pianist as well as a composer of worth. He very shortly reestablished his reputation as a virtuoso. Ignaz Moscheles wrote in 1855 what would become a widespread opinion about Rubinstein: "In power and execution he is inferior to no one."

As was the penchant at the time, much of what Rubinstein played were his own compositions. At several concerts, Rubinstein alternated between conducting his orchestral works and playing as soloist in one of his piano concertos. One high point for him was leading the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra in his Ocean Symphony on November 16, 1854; as this was considered one of the most prestigious places to have a musical work performed, having the Ocean heard there was considered a high honor. Although reviews were mixed about Rubinstein's merits as a composer, they were more favorable about him as a performer when he played a solo recital a few weeks later.

Rubinstein spent one tour break, in the winter of 1856-7, with Elena Pavlovna and much of the Imperial royal family at Nice. These three months would become crucial ones. Rubinstein had already

noted both his patroness's great intelligence and her great influence in

terms of reform over her brother Nicholas I. (She would exercise a similar influence over her nephew, Alexander II, resulting in, among other things, the freeing of the serfs.)

Now patroness and artist, with others present, began discussing plans

to raise the level of musical education in their homeland. These

discussions bore fruit at first in the founding of the Russian Musical Society (RMS) in 1859.

The opening of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, the first music school in Russia and an outgrowth of the RMS, followed in 1862. Rubinstein not only founded it and was its first director but also recruited an imposing pool of talent for its faculty.

Some in Russian society were surprised that a Russian music school would actually attempt to be Russian. One "fashionable lady," when told by Rubinstein that classes would be taught in Russian and not a foreign language, exclaimed, "What, music in Russian! That is an original idea!" Rubinstein adds,

And surely it was surprising that the theory of Music was to be taught for the first time in the Russian language at our Conservatory.... Hitherto, if any one wished to study it, he was obliged to take lessons from a foreigner, or to go to Germany.

There were also those who feared the school would not be Russian enough. Rubinstein drew a tremendous amount of criticism from the Russian nationalist music group known as The Five. Mikhail Zetlin, in his book on The Five, writes,

The very idea of a conservatory implied, it is true, a spirit of academism which could easily turn it into a stronghold of routine, but then the same could be said of conservatories all over the world. Actually the Conservatory did raise the level of musical culture in Russia. The unconventional way chosen by Balakirev and his friends was not necessarily the right one for everybody else.

It was during this period that Rubinstein drew his greatest success as a composer, beginning with his Fourth Piano Concerto in 1864 and culminating with his opera The Demon in 1871. Between these two works are the orchestral works Don Quixote, which Tchaikovsky found "interesting and well done," though "episodic," and the opera Ivan IV Grozniy, which was premiered by Balakirev. Borodin commented on Ivan IV that "the music is good, you just cannot recognize that it is Rubinstein. There is nothing that is Mendelssohnian, nothing as he used to write formerly."

By 1867, ongoing tensions with the Balakirev camp, along with related

matters, led to intense dissension within the Conservatory's faculty.

Rubinstein resigned and returned to touring throughout Europe.

Unlike his previous tours, he began increasingly featuring the works of

other composers. In previous tours, Rubinstein had played primarily his

own works.

At the behest of the Steinway & Sons piano company, Rubinstein toured the United States during the 1872-3 season. Steinway's contract with Rubinstein called on him to give 200 concerts at the then unheard - of rate of 200 dollars per concert (payable in gold — Rubinstein distrusted both United States banks and United States paper money), plus all expenses paid. Rubinstein stayed in America 239 days, giving 215 concerts — sometimes two and three a day in as many cities. Rubinstein wrote of his American experience,

May Heaven preserve us from such slavery! Under these conditions there is no chance for art — one simply grows into an automaton, performing mechanical work; no dignity remains to the artist; he is lost.... The receipts and the success were invariably gratifying, but it was all so tedious that I began to despise myself and my art. So profound was my dissatisfaction that when several years later I was asked to repeat my American tour, I refused pointblank...

Despite his misery, Rubinstein made enough money from his American

tour to give him financial security for the rest of his life. Upon his

return to Russia, he "hastened to invest in real estate", purchasing a dacha in Peterhof, not far from Saint Petersburg, for himself and his family.

Rubinstein continued to make tours as a pianist and give appearances as a conductor. In 1887, he returned to the Saint Petersburg Conservatory with the goal of improving overall standards. He removed inferior students, fired and demoted many professors, made entrance and examination requirements more stringent and revised the curriculum. He led semi - weekly teachers' classes through the whole keyboard literature and gave some of the more gifted piano students personal coaching. During the 1889 - 90 academic year he gave weekly lecture recitals for the students. He resigned again — and left Russia — in 1891 over Imperial demands that Conservatory admittance, and later annual prizes to students, be awarded along racial quotas instead of purely by merit. These quotas were effectively to disadvantage Jews. Rubinstein resettled in Dresden and started giving concerts again in Germany and Austria. Nearly all of these concerts were charity benefit events.

Rubinstein also coached a few pianists and taught his only private piano student, Josef Hofmann. Hofmann would become one of the finest keyboard artists of the 20th century.

Despite his sentiments on ethnic politics in Russia, Rubinstein returned there occasionally to visit friends and family. He gave his final concert in Saint Petersburg on January 14, 1894. With his health failing rapidly, Rubinstein moved back to Peterhof in the summer of 1894. He died there on November 20 of that year, having suffered from heart disease for some time.

The former Troitskaya street in Saint Petersburg where he lived is now named after him.

Many of Rubinstein's contemporaries felt he bore a striking resemblance to Ludwig van Beethoven. Ignaz Moscheles, who had known Beethoven intimately, wrote, "Rubinstein's features and short, irrepressible hair remind me of Beethoven." Liszt referred to Rubinstein as "Van II." Rubinstein was even rumored to be the illegitimate son of Beethoven. Rubinstein neither confirmed nor denied this rumor. Neither did he remind anyone that he was born more than two years after Beethoven had died.

This resemblance to Beethoven was also felt to be in Rubinstein's keyboard playing. Under his hands, it was said, the piano erupted volcanically. Audience members wrote of going home limp after one of his recitals, knowing they had witnessed a force of nature.

Sometimes Rubinstein's playing was too much for listeners to handle. American pianist Amy Fay, who wrote extensively on the European classical music scene, admitted that while Rubinstein "has a gigantic spirit in him, and is extremely poetic and original ... for an entire evening he is too much. Give me Rubinstein for a few pieces, but Tausig for a whole evening." She heard Rubinstein play "a terrific piece by Schubert," reportedly the Wanderer Fantasie. The performance gave her such a violent headache that the rest of the recital was ruined for her.

Clara Schumann proved especially vehement. After she heard him play the Mendelssohn C minor Trio in 1857, she wrote that "he so rattled it off that I did not know how to control myself ... and often he so annihilated fiddle and cello that I ... could hear nothing of them."

Nor had things improved in Clara's view a few years later, when Rubinstein gave a concert in Breslau. She noted her disapproval in her diary:

I was furious, for he no longer plays. Either there is a perfectly wild noise or else a whisper with the soft pedal down. And a would - be cultured audience puts up with a performance like that!

On the other hand, when Rubinstein played Beethoven's "Archduke" Trio with violinist Leopold Auer and cellist Alfredo Piatti in 1868, Auer recalls:

It was the first time I had heard this great artist play. He was most amiable at the rehearsal.... To this day I can recall how Rubinstein sat down at the piano, his leonine head thrown back slightly, and began the five opening measures of the principal theme.... It seemed to me I had never before heard the piano really played. The grandeur of style with which Rubinstein presented those five measures, the beauty of tone his softness of touch secured, the art with which he manipulated the pedal, are indescribable ...

Violinist and composer Henri Vieuxtemps adds:

His power over the piano is something undreamt of; he transports you into another world; all that is mechanical in the instrument is forgotten. I am still under the influence of the all - embracing harmony, the scintillating passages and thunder of Beethoven's Sonata Op. 57 [Appassionata], which Rubinstein executed for us with unimagined mastery.

Viennese music critic Eduard Hanslick expressed what Schonberg calls "the majority point of view" in an 1884 review. After complaining of the over - three - hour length of Rubinstein's recital, Hanslick admits that the sensual element of the pianist's playing gives pleasure to listeners. Both Rubinstein's virtues and flaws, Hanslick commented, spring from an untapped natural strength and elemental freshness. "Yes, he plays like a god," Hanslick writes in closing, "and we do not take it amiss if, from time to time, he changes, like Jupiter, into a bull".

Sergei Rachmaninoff's fellow piano student Matvey Pressman adds,

He enthralled you by his power, and he captivated you by the elegance and grace of his playing, by his tempestuous, fiery temperament and by his warmth and charm. His crescendo had no limits to the growth of the power of its sonority; his diminuendo reached an unbelievable pianissimo, sounding in the most distant corners of a huge hall. In playing, Rubinstein created, and he created inimitably and with genius. He often treated the same program absolutely differently when he played it the second time, but, more astoundingly still, everything came out wonderfully on both occasions.

Rubinstein was also adept at improvisation — a practice at which Beethoven had excelled but by Rubinstein's time was on the wane. Composer Karl Goldmark wrote of one recital where Rubinstein improvised on a motive from the last movement of Beethoven's Eighth Symphony:

He counterpointed it in the bass; then developed it first as a canon, next as a four - voiced fugue, and again transformed it into a tender song. He then returned to Beethoven's original form, later changing it to a gay Viennese waltz, with its own peculiar harmonies, and finally dashed into cascades of brilliant passages, a perfect storm of sound in which the original theme was still unmistakable. It was superb."

Villoing had worked with Rubinstein on hand position and finger dexterity. From watching Liszt, Rubinstein had learned about freedom of arm movement. Theodor Leschetizky, who taught piano at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory when it opened, likened muscular relaxation at the piano to a singer's deep breathing. He would remark to his students about "what deep breaths Rubinstein used to take at the beginning of long phrases, and also what repose he had and what dramatic pauses."

In his book The Great Pianists, former New York Times critic Harold C. Schonberg describes Rubinstein's playing as that "of extraordinary breadth, virility and vitality, immense sonority and technical grandeur in which all too often technical sloppiness asserted itself." When caught up in the moment of performance, Rubinstein did not seem to care how many wrong notes he played as long as his conception of the piece he was playing came through. Rubinstein himself admitted, after a concert in Berlin in 1875, "If I could gather up all the notes that I let fall under the piano, I could give a second concert with them."

Part of the problem might have been the sheer size of Rubinstein's hands. They were huge, and many observers commented on them. Josef Hofmann observed that Rubinstein's fifth finger "was as thick as my thumb — think of it! Then his fingers were square at the ends, with cushions on them. It was a wonderful hand.". Pianist Josef Lhevinne described them as "fat, pudgy ... with fingers so broad at the finger tips that he often had difficulty in not striking two notes at once." The German piano teacher Ludwig Deppe advised American pianist Amy Fay to watch carefully how Rubinstein struck his chords: "Nothing cramped about him! He spreads his hands as if he were going to take in the universe, and takes them up with the greatest freedom and abandon!"

Because of the slap - dash moments in Rubinstein's playing, some more

academic, polished players, especially German - trained ones, seriously

questioned Rubinstein's greatness. Those who valued interpretation as

much or more than pure technique found much to praise. Pianist and

conductor Hans von Bülow called Rubinstein "the Michelangelo of music." The German critic Ludwig Rellstab called him "the Hercules of the piano; the Jupiter Tonans of the instrument."

Schonberg has assessed Rubinstein's piano tone the most sensuous of any of the great pianists . Fellow pianist Rafael Joseffy compared it to "a golden French horn." Rubinstein himself told an interviewer, "Strength with lightness, that is one secret of my touch.... I have sat hours trying to imitate the timbre of [Italian tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini's] voice in my playing."

Pressman attested to the singing quality of Rubinstein's playing, and much more: "His tone was strikingly full and deep. With him the piano sounded like a whole orchestra, not only as far as the power of sound was concerned but in the variety of timbres. With him, the piano sang as Patti sang, as Rubini sang."

Rubinstein told the young Rachmaninoff

how he achieved that tone. "Just press upon the keys until the blood

oozes from your fingertips". When he wanted to, Rubinstein could play

with extreme lightness, grace and delicacy. He rarely displayed that

side of his nature, however. He had learned quickly that audiences came

to hear him thunder, so he accommodated them. Rubinstein's forceful

playing and powerful temperament made an especially strong impression

during his American tour, where playing of this kind had never been

heard before. During this tour, Rubinstein received more press attention

than any other figure until the appearance of Ignacy Jan Paderewski a generation later.

Rubinstein's concert programs were often gargantuan. Hanslick mentioned in his 1884 review that the pianist played more than 20 pieces in one concert in Vienna, including three sonatas (the Schumann F sharp minor plus Beethoven's D minor and Op. 101 in A). Rubinstein was a man with an extremely robust constitution and apparently never tired; audiences apparently stimulated his adrenals to the point where he acted like a superman. He had a colossal repertoire and an equally colossal memory until he turned 50, when he began to have memory lapses and had to play from the printed note.

Rubinstein was most famous for his series of historical recitals — seven consecutive concerts covering the history of piano music. Each of these programs was enormous. The second, devoted to Beethoven sonatas, consisted of the Moonlight, D minor, Waldstein, Appassionata, E minor, A major (Op. 101), E major (Op. 109) and C minor (Op. 111). Again, this was all included in one recital. The fourth concert, devoted to Schumann, contained the Fantasy in C, Kreisleriana, Symphonic Studies, Sonata in F sharp minor, a set of short pieces and Carnival. This did not include encores, which Rubinstein sprayed liberally at every concert.

Rubinstein concluded his American tour with this series, playing the seven recitals over a nine day period in New York in May 1873.

Rubinstein played this series of historical recitals in Russia and

throughout Eastern Europe. In Moscow he gave this series on consecutive

Tuesday evenings in the Hall of the Nobility, repeating each concert the

following morning in the German Club for the benefit of students, free

of charge.

Sergei Rachmaninoff first attended Rubinstein's historical concerts as a twelve year old piano student. Forty - four years later he told his biographer Oscar von Riesemann, "[His playing] gripped my whole imagination and had a marked influence on my ambition as a pianist"

Rachmaninoff explained to von Riesemann, "It was not so much his magnificent technique that held one spellbound as the profound, spiritually refined musicianship, which spoke from every note and every bar he played and singled him out as the most original and unequaled pianist in the world."

Rachmaninoff's detailed description to von Riesemann is of interest:

Once he repeated the whole finale of [Chopin's] Sonata in B minor, perhaps he had not succeeded in the short crescendo at the end as he would have wished. One listened entranced, and could have heard the passage over and over again, so unique was the beauty of tone.... I have never heard the virtuoso piece Islamey by Balakirev, as Rubinstein played it, and his interpretation of Schumann's little fantasy The Bird as Prophet was inimitable in poetic refinement: to describe the diminuendo of the pianissimo at the end of the "fluttering away of the little bird" would be hopelessly inadequate. Inimitable, too, was the soul stirring imagery in the Kreisleriana, the last (G minor) passage of which I have never heard anyone play in the same manner. One of Rubinstein's greatest secrets was his use of the pedal. He himself very happily expressed his ideas on the subject when he said, "The pedal is the soul of the piano." No pianist should ever forget this.

Rachmaninoff biographer Barrie Martyn suggests that it might not have been by chance that the two pieces Rachmaninoff singled out for praise from Rubinstein's concerts — Beethoven's Appassionata and Chopin's "Funeral March" Sonata — both became cornerstones of Rachmaninoff's own recital programs. Martyn also maintains that Rachmaninoff may have based his interpretation of the Chopin sonata on Rubinstein's traversal, pointing out similarities between written accounts of Rubinstein's version and Rachmaninoff's audio recording of the work.

Rachmaninoff admitted that Rubinstein was not note perfect at these concerts, remembering a memory lapse during Balakirev's Islamey, where Rubinstein improvised in the style of the piece until remembering the rest of it four minutes later. In Rubinstein's defense, however, Rachmaninoff said that "for every possible mistake [Rubinstein] may have made, he gave, in return, ideas and musical tone pictures that would have made up for a million mistakes."

Rubinstein conducted the Russian Musical Society

programs from the organization's inception in 1859 until his

resignation from it and the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1867. He

also did his share of guest conducting both before and after his tenure

with the RMS. Rubinstein at the podium was as temperamental as when at

the keyboard, provoking mixed reactions amongst both orchestral

musicians and audiences.

By 1850, Rubinstein had decided that he did not want to be known solely as a pianist, "but as a composer performing his symphonies, concertos, operas, trios, etc." Rubinstein was a prolific composer, writing no fewer than twenty operas (notably The Demon, written after Lermontov's Romantic poem, and its successor The Merchant Kalashnikov), five piano concertos, six symphonies and a large number of solo piano works along with a substantial output of works for chamber ensemble, two concertos for cello and one for violin, free standing orchestral works and tone poems (including one entitled Don Quixote). Edward Garden writes in the New Grove,

Rubinstein composed assiduously during all periods of his life. He was able, and willing, to dash off for publication half a dozen songs or an album of piano pieces with all too fluent ease in the knowledge that his reputation would ensure a gratifying financial reward for the effort involved.

Rubinstein and Mikhail Glinka, considered the first important Russian classical composer, had both studied in Berlin with pedagogue Siegfried Dehn. Glinka, as Dehn's student 12 years before Rubinstein, used the opportunity to amass greater reserves of compositional skill that he could use to open up a whole new territory of Russian music. Rubinstein, conversely, chose to exercise his compositional talents within the German styles illustrated in Dehn's teaching. Robert Schumann and Felix Mendelssohn were the strongest influences on Rubinstein's music.

Consequently, Rubinstein's music demonstrates none of the nationalism of The Five. Rubinstein also had a tendency to rush in composing his pieces, resulting in good ideas such as those in his Ocean Symphony being developed in less - than - exemplary ways. As Paderewski was later to remark,"He had not the necessary concentration of patience for a composer...." 'He was prone to indulge in grandiloquent cliches at moments of climax, preceded by over - lengthy rising sequences which were subsequently imitated by Tchaikovsky in his less - inspired pieces'.

Nevertheless, Rubinstein's Fourth Piano Concerto

greatly influenced Tchaikovsky's piano concertos, especially the first (1874-5), and the superb finale, with its introduction and scintillating principal subject, is the basis of very similar material at the beginning of the finale of Balakirev's Piano Concerto in E-flat major [...] The first movement of Balakirev's concerto had been written, partially under the influence of Rubinstein's Second Concerto, in the 1860s.

After Rubinstein's death, his works began to lose popularity, although his piano concerti remained in the repertoire in Europe until the First World War, and his principal works have retained a toehold in the Russian concert repertoire. Perhaps somewhat lacking in individuality, Rubinstein's music was unable to compete either with the established classics or with the new Russian style of Stravinsky and Prokofiev.

Over recent years, his work has been performed a little more often

both in Russia and abroad, and has often met with positive criticism. Amongst his better known works are the opera The Demon, his Piano Concerto No. 4, and his Symphony No. 2, known as The Ocean.

Rubinstein was as well known during his lifetime for his sarcasm as well as his sometimes penetrating insight. During one of Rubinstein's visits to Paris, French pianist Alfred Cortot played the first movement of Beethoven's Appassionata for him. After a long silence, Rubinstein told Cortot, "My boy, don't you ever forget what I am going to tell you. Beethoven's music must not be studied. It must be reincarnated." Cortot reportedly never forgot those words.

Rubinstein's own piano students were held just as accountable: he wanted them to think about the music they were playing, matching the tone to the piece and the phrase. His manner with them was a combination of raw, sometimes violent criticism and good humor. Hofmann wrote of one such lesson:

Once I played a Liszt rhapsody pretty badly. After a little of it, Rubinstein said, "The way you play this piece would be all right for Auntie or Mamma." Then rising and coming toward me, he said, "Now let us see how we play such things." [...] I began again, but I had not played more than a few measures when Rubinstein said loudly, "Have you begun?" "Yes, Master, I certainly have." "Oh," said Rubinstein vaguely, "I didn't notice." [...] Rubinstein did not so much instruct me. Merely he let me learn from him ... If a student, by his own study and mental force, reached the desired point which the musician's wizardry had made him see, he gained reliance in his own strength, knowing he would always find that point again even though he should lose his way once or twice, as everyone with an honest aspiration is liable to do.

Rubinstein's insistence on absolute fidelity to the printed note surprised Hofmann, since he had heard his teacher take liberties himself in his concerts. When he asked Rubinstein to reconcile this paradox, Rubinstein answered, as many teachers have through the ages, "When you are as old as I am, you may do as I do." Then Rubinstein added, "If you can".

Nor did Rubinstein adjust the tenor of his comments for those of high

rank. After Rubinstein had reassumed the directorship of the Saint

Petersburg Conservatory, Tsar Alexander III

donated the dilapidated old Bolshoi Theater as the Conservatory's new

home — without the funds needed to restore and restructure the facility.

At a reception given in the monarch's honor, the Tsar asked Rubinstein

if he was pleased with this gift. Rubinstein replied bluntly, to the

crowd's horror, "Your Imperial Majesty, if I gave you a beautiful

cannon, all mounted and embossed, with no ammunition, would you like

it?"

Louis Moreau Gottschalk (May 8, 1829 – December 18, 1869) was an American composer and pianist, best known as a virtuoso performer of his own romantic piano works. He spent most of his working career outside of the United States.

Gottschalk was born to a Jewish businessman from London and a Creole mother in New Orleans, where he was exposed to a variety of musical traditions. He had six brothers and sisters, five of whom were half siblings by his father's mulatto mistress. His family lived for a time in a tiny cottage at Royal and Esplanade in the Vieux Carré. Louis later moved in with relatives at 518 Conti Street; his maternal grandmother Buslé and his nurse Sally had both been born in Saint - Domingue (known later as Haiti). Gottschalk played the piano from an early age and was soon recognized as a wunderkind by the New Orleans bourgeois establishment. In 1840, he gave his informal public debut at the new St. Charles Hotel.

Only two years later at the age of 13, Gottschalk left the United States and sailed to Europe, as he and his father realized a classical training was required to fulfill his musical ambitions. The Paris Conservatoire, however, rejected his application without hearing him on the grounds of his nationality; Pierre Zimmermann, head of the piano faculty, commented that "America is a country of steam engines". Gottschalk gradually gained access to the musical establishment through family friends.

After Gottschalk returned to the United States in 1853, he traveled extensively; a sojourn in Cuba during 1854 was the beginning of a series of trips to Central and South America. By the 1860s, Gottschalk had established himself as the best known pianist in the New World. Although born and reared in New Orleans, he was a supporter of the Union cause during the American Civil War. He returned to his native city only occasionally for concerts, but Gottschalk always introduced himself as a New Orleans native.

In May 1865, he was mentioned in a San Francisco newspaper as having "traveled 95,000 miles by rail and given 1,000 concerts". However, he was forced to leave the United States later that year because of a scandalous affair with a student at the Oakland Female Seminary in Oakland, California. He never returned to the U.S.

Gottschalk chose to travel to South America, where he continued to give frequent concerts. During one of these concerts, in Rio de Janeiro on November 24, 1869, he collapsed from having contracted malaria. Just before his collapse, he had finished playing his romantic piece Morte!! (interpreted as "she is dead"), although the actual collapse occurred just as he started to play his celebrated piece Tremolo. Gottschalk never recovered from the collapse.

Three weeks later, on December 18, 1869, at the age of 40, he died at his hotel in Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, probably from an overdose of quinine. [According to an essay by Jeremy Nicholas for the booklet accompanying the recording "Gottschalk Piano Music," performed by Philip Martin on the Hyperion label, "He died . . . of empyema, the result of a ruptured abscess in the abdomen."]

In 1870 his remains were returned to the United States and were interred at the Green - Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. His burial spot was originally marked by a magnificent marble monument, topped by an "Angel of Music" statue, which disappeared some time during the mid 20th century. The Green - Wood Cemetery is seeking donations to restore the monument in his honor, the cost of which they estimate at $200,000.

His grand nephew Louis Ferdinand Gottschalk was a notable composer of silent film and musical theatre scores.

Gottschalk's music was very popular during his lifetime, and his earliest compositions created a sensation in Europe. Early pieces like "Le Bananier" and "Bamboula" were based on Gottschalk's memories of the music he heard during his youth in Louisiana. In this context, some of Gottschalk's work, such as the 13 minute opera Escenas campestres, retains a wonderfully innocent sweetness and charm.

Various pianists later recorded his piano music. The first important recordings of his orchestral music, including the symphony A Night in the Tropics, were made for Vanguard Records by Maurice Abravanel and the Utah Symphony Orchestra. Vox Records issued a multi - disc collection of his music, which was later reissued on CD. This included world premiere recordings of the original orchestrations of both symphonies and other works, which were conducted by Igor Buketoff and Samuel Adler. More recently, Philip Martin has recorded most of the complete extant piano music for Hyperion Records.

Author Howard Breslin wrote a historical novel about Gottschalk titled Concert Grand in 1963.