<Back to Index>

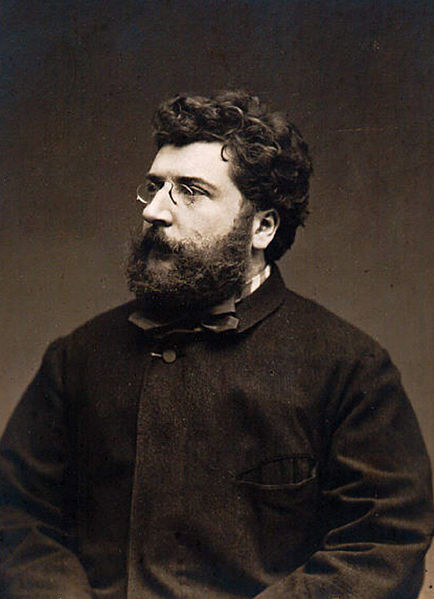

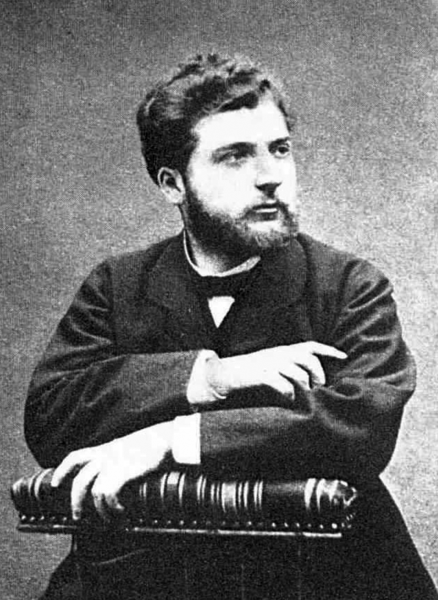

- Composer Georges Bizet, 1838

- Composer Max Christian Friedrich Bruch, 1838

- Composer Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, 1839

PAGE SPONSOR

Georges Bizet, formally Alexandre César Léopold Bizet, (25 October 1838 – 3 June 1875) was a French composer, mainly of operas. In a career cut short by his early death, he achieved few successes before his final work, Carmen, became one of the most popular and frequently performed works in the entire opera repertory.

During a brilliant student career at the Conservatoire de Paris, Bizet won many prizes, including the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1857. He was recognized as an outstanding pianist, though he chose not to capitalize on this skill and rarely performed in public. Returning to Paris after almost three years in Italy, he found that the main Parisian opera theaters preferred the established classical repertoire to the works of newcomers. His keyboard and orchestral compositions were likewise largely ignored; as a result, his career stalled, and he earned his living mainly by arranging and transcribing the music of others. Restless for success, he began many theatrical projects during the 1860s, most of which were abandoned. Neither of the two operas that reached the stage — Les pêcheurs de perles and La jolie fille de Perth — was immediately successful.

After the Franco - Prussian War of 1870 – 71, in which Bizet served in the National Guard, he had little success with his one act opera Djamileh, though an orchestral suite derived from his incidental music to Alphonse Daudet's play L'Arlésienne was instantly popular. The production of Bizet's final opera Carmen was delayed through fears that its themes of betrayal and murder would offend audiences. After its premiere on 3 March 1875, Bizet was convinced that the work was a failure; he died of a heart attack three months later, unaware that it would prove a spectacular and enduring success.

Bizet's marriage to Geneviève Halévy was intermittently happy and produced one son. After his death, his work, apart from Carmen,

was generally neglected. Manuscripts were given away or lost, and

published versions of his works were frequently revised and adapted by

other hands. He founded no school and had no obvious disciples or

successors. After years of neglect, his works began to be performed more

frequently in the 20th century. Later commentators have acclaimed him

as a composer of brilliance and originality whose premature death was a

significant loss to French musical theater.

Georges Bizet was born in Paris on 25 October 1838. He was registered as Alexandre César Léopold, but baptized as "Georges" on 16 March 1840, and was known by this name for the rest of his life. His father, Adolphe Bizet, had been a hairdresser and wigmaker before becoming a singing teacher despite his lack of formal training. He also composed a few works, including at least one published song. In 1837 Adolphe married Aimée Delsarte, against the wishes of her family who considered him a poor prospect; the Delsartes, though impoverished, were a cultured and highly musical family. Aimée was an accomplished pianist, while her brother François Delsarte was a distinguished singer and teacher who performed at the courts of both Louis Philippe and Napoleon III. François Delsarte's wife Rosine, a musical prodigy, had been an assistant professor of solfège at the Conservatoire de Paris at the age of 13.

Georges, an only child, showed early aptitude for music and quickly picked up the basics of musical notation from his mother, who probably gave him his first piano lessons. By listening at the door of the room where Adolphe conducted his classes, Georges learned to sing difficult songs accurately from memory, and developed an ability to identify and analyze complex chordal structures. This precocity convinced his ambitious parents that he was ready to begin studying at the Conservatoire, even though he was still only nine years old (the minimum entry age was 10). Georges was interviewed by Joseph Meifred, the horn virtuoso who was a member of the Conservatoire's Committee of Studies. Meifred was so struck by the boy's demonstration of his skills that he waived the age rule and offered to take him as soon as a place became available.

Bizet was admitted to the Conservatoire on 9 October 1848, two weeks before his 10th birthday. He made an early impression; within six months he had won first prize in solfège, a feat that impressed Pierre - Joseph - Guillaume Zimmermann, the Conservatoire's former professor of piano. Zimmermann gave Bizet private lessons in counterpoint and fugue, which continued until the old man's death in 1853. Through these classes Bizet met Zimmermann's son - in - law, the composer Charles Gounod,

who became a lasting influence on the young pupil's musical

style — although their relationship was often strained in later years. Under the tuition of Antoine François Marmontel,

the Conservatoire's professor of piano, Bizet's pianism developed

rapidly; he won the Conservatoire's second prize for piano in 1851, and

first prize the following year. Bizet would later write to Marmontel:

"In your class one learns something besides the piano; one becomes a

musician".

Bizet's first preserved compositions, two wordless songs for soprano, date from around 1850. In 1853 he joined Fromental Halévy's composition class, and began to produce works of increasing sophistication and quality. Two of his songs, "Petite Marguerite" and "La Rose et l'abeille", were published in 1854. In 1855 he wrote an ambitious overture for a large orchestra, and prepared four - hand piano versions of two of Gounod's works: the opera La nonne sanglante and the Symphony in D. Bizet's work on the Gounod symphony inspired him, shortly after his seventeenth birthday, to write his own symphony, which bore a close resemblance to Gounod's — note for note in some passages. Bizet's symphony was subsequently lost, rediscovered in 1933 and finally performed in 1935.

In 1856 Bizet competed for the prestigious Prix de Rome. His entry was not successful, but nor were any of the others; the musician's prize was not awarded that year. After this rebuff Bizet entered an opera competition which Jacques Offenbach had organized for young composers, with a prize of 1,200 francs. The challenge was to set the one act libretto of Le docteur Miracle by Léon Battu and Ludovic Halévy. The prize was awarded jointly to Bizet and Charles Lecocq, a compromise which years later Lecocq criticized on the grounds of the jury's manipulation by Fromental Halévy in favor of Bizet. As a result of his success Bizet became a regular guest at Offenbach's Friday evening parties, where among other musicians he met the aged Gioachino Rossini, who presented the young man with a signed photograph. Bizet was a great admirer of Rossini's music, and wrote not long after their first meeting that "Rossini is the greatest of them all, because like Mozart, he has all the virtues".

For his 1857 Prix de Rome entry Bizet, with Gounod's enthusiastic approval, chose to set the cantata Clovis et Clotilde by Amédée Burion. Bizet was awarded the prize after a ballot of the members of the Académie des Beaux - Arts overturned the judges' initial decision, which was in favor of the oboist Charles Colin.

Under the terms of the award, Bizet received a financial grant for five

years, the first two to be spent in Rome, the third in Germany and the

final two in Paris. The only other requirement was the submission each

year of an "envoi", a piece of original work to the satisfaction of the

Académie. Before his departure for Rome in December 1857, Bizet's prize

cantata was performed at the Académie to an enthusiastic reception.

On 27 January 1858 Bizet arrived at the Villa Medici, a 16th century palace that since 1803 had housed the French Académie in Rome and which he described in a letter home as "paradise". Under its director, the painter Jean - Victor Schnetz, the villa provided an ideal environment in which Bizet and his fellow laureates could pursue their artistic endeavors. Bizet relished the convivial atmosphere, and quickly involved himself in the distractions of its social life; in his first six months in Rome his only composition was a Te Deum written for the Rodrigues Prize, a competition for a new religious work open to Prix de Rome winners. This piece failed to impress the judges, who awarded the prize to Adrien Barthe, the only other entrant. Bizet was discouraged to the extent that he vowed to write no more religious music. His Te Deum remained forgotten and unpublished until 1971.

Through the winter of 1858 – 59 Bizet worked on his first envoi, an opera buffa setting of Carlo Cambiaggio's libretto Don Procopio. Under the terms of his prize, Bizet's first envoi was supposed to be a mass, but following his Te Deum

experience he was averse to writing religious music. He was

apprehensive about how this breach of the rules would be received at the

Académie, but their response to Don Procopio was initially positive, with praise for the composer's "easy and brilliant touch" and "youthful and bold style."

For his second envoi, not wishing to test the Académie's tolerance too far, Bizet proposed to submit a quasi - religious work in the form of a secular mass on a text by Horace. This work, entitled Carmen Saeculare, was intended as a song to Apollo and Diana. No trace exists, and it is unlikely that Bizet ever started it. A tendency to conceive ambitious projects, only to quickly abandon them, became a feature of Bizet's Rome years; in addition to Carmen Saeculare he considered and discarded at least five opera projects, two attempts at a symphony, and a symphonic ode on the theme of Ulysses and Circe. After Don Procopio Bizet completed only one further work in Rome, the symphonic poem Vasco da Gama. This replaced Carmen Saeculare as his second envoi, and was well received by the Académie, though swiftly forgotten thereafter.

In the summer of 1859 Bizet and several companions traveled in the mountains and forests around Anagni and Frosinone. They also visited a convict settlement at Anzio; Bizet sent an enthusiastic letter to Marmontel, recounting his experiences. In August he made an extended journey south to Naples and Pompeii,

where he was unimpressed with the former but delighted with the latter:

"Here you live with the ancients; you see their temples, their

theaters, their houses in which you find their furniture, their kitchen

utensils..."

Bizet began sketching a symphony based on his Italian experiences, but

made little immediate headway; the project, which became his Roma symphony, was not finished until 1868.

On his return to Rome Bizet successfully requested permission to extend

his stay in Italy into a third year, rather than going to Germany, so

that he could complete "an important work" (which has not been

identified). In September 1860, while visiting Venice with his friend and fellow laureate Ernest Guiraud, Bizet received news that his mother was gravely ill in Paris, and made his way home.

Back in Paris with two years of his grant remaining, Bizet was temporarily secure financially, and could ignore for the moment the difficulties that other young composers faced in the city. The two state - subsidized opera houses, the Opéra and the Opéra - Comique, each presented traditional repertoires that tended to stifle and frustrate new homegrown talent; only eight of the 54 Prix de Rome laureates between 1830 and 1860 had had works staged at the Opéra. Although French composers were better represented at the Opéra - Comique, the style and character of productions had remained largely unchanged since the 1830s. A number of smaller theaters catered for operetta, a field in which Offenbach was then paramount, while the Théâtre Italien specialized in second rate Italian opera. The best prospect for aspirant opera composers was the Théâtre Lyrique company which, despite repeated financial crises, operated intermittently in various premises under its resourceful manager Léon Carvalho. This company had staged the first performances of Gounod's Faust and his Roméo et Juliette, and of a shortened version of Berlioz's Les Troyens.

On 13 March 1861 Bizet attended the Paris premiere of Wagner's opera Tannhäuser, a performance greeted by audience riots that were stage managed by the influential Jockey - Club de Paris.

Despite this distraction, Bizet revised his opinions of Wagner's music,

which he had previously dismissed as merely eccentric. He now declared

Wagner "above and beyond all living composers". Thereafter, accusations of "Wagnerism" were often laid against Bizet, throughout his compositional career.

As a pianist, Bizet had showed considerable skill from his earliest

years. A contemporary asserted that he could have assured a future on

the concert platform, but chose to conceal his talent "as though it were

a vice". In May 1861 Bizet gave a rare demonstration of his virtuoso skills when, at a dinner party at which Liszt

was present, he astonished everyone by playing on sight, flawlessly,

one of the maestro's most difficult pieces. Liszt commented: "I thought

there were only two men able to surmount the difficulties ... there are

three, and ... the youngest is perhaps the boldest and most brilliant".

Bizet's third envoi was delayed for nearly a year by the prolonged illness and eventual death, in September 1861, of his mother. He eventually submitted a trio of orchestral works: an overture entitled La Chasse d'Ossian, a scherzo and a funeral march. The overture has been lost; the scherzo was later absorbed into the Roma symphony, and the funeral march music was adapted and used in Les pêcheurs de perles. In 1862 Bizet fathered a child with the family's housekeeper, Marie Reiter. The boy was brought up to believe that he was Adolphe Bizet's child; only on her deathbed in 1913 did Reiter reveal her son's true paternity.

Bizet's fourth and final envoi, which occupied him for much of 1862, was a one act opera, La guzla de l'émir.

As a state subsidised theater, the Opéra - Comique was obliged from time

to time to stage the works of Prix de Rome laureates, and La guzla duly went into rehearsal in 1863. However, in April Bizet received an offer, which originated from Count Walewski, to write a three act opera, Les pêcheurs de perles, using a libretto by Michel Carré and Eugène Cormon.

Because a condition of the offer was that the opera should be the

composer's first publicly staged work, Bizet hurriedly withdrew La guzla from production and incorporated parts of its music into the new opera. The first performance of Les pêcheurs de perles,

by the Théâtre Lyrique company, was on 30 September. Critical opinion

was generally hostile, though Berlioz praised the work, writing that it

did "does M. Bizet the greatest honor". Public reaction was lukewarm, and the opera's run ended after 18 performances. It was not performed again until 1886.

When his Prix de Rome grant expired, Bizet soon found he could not make a living from writing music. He accepted piano pupils and some composition students, two of whom, Edmond Galabert and Paul Lacombe, became his close friends. He also worked as an accompanist at rehearsals and auditions for various staged works, including Berlioz's oratorio L'enfance du Christ and Gounod's opera Mireille. However, his main work in this period was as an arranger of others' works. He made piano transcriptions for hundreds of operas and other pieces, and prepared vocal scores and orchestral arrangements for all kinds of music. He was also, briefly, a music critic for La Revue Nationale et Étrangère, under the assumed name of "Gaston de Betzi". Bizet's single contribution in this capacity appeared on 3 August 1867, after which he quarreled with the magazine's new editor and resigned.

Since 1862 Bizet had been working intermittently on Ivan IV, an opera based on the life of Ivan the Terrible. Carvalho failed to deliver on his promise to produce it, so in December 1865 Bizet offered it to the Opéra, which rejected it; the work remained unperformed until 1946. In July 1866 Bizet signed another contract with Carvalho, for La jolie fille de Perth, the libretto for which, by J.H. Vernoy de Saint - Georges after Sir Walter Scott, is described by Bizet's biographer Winton Dean as "the worst Bizet was ever called upon to set". Problems over the casting and other issues delayed its premiere for a year before it was finally performed by the Théâtre Lyrique on 26 December 1867. Its press reception was more favorable than that for any of Bizet's other operas; Le Ménestral's critic hailed the second act as "a masterpiece from beginning to end". Despite the opera's success, Carvalho's financial difficulties meant a run of only 18 performances.

While La jolie fille was in rehearsal, Bizet worked with three other composers, each of whom contributed a single act to a four act operetta Marlborough s'en va-t-en guerre.

When the work was performed at the Théâtre de

l'Athénée on 13 December 1867 it was a great success, and

the Revue et Gazette Musicale's

critic lavished particular praise on Bizet's act: "Nothing could be

more stylish, smarter and, at the same time, more distinguished". Bizet also found time to finish his long gestating Roma

symphony, and wrote numerous keyboard works and songs. Nevertheless,

this period of Bizet's life was marked by significant disappointments.

At least two projected operas were abandoned with little or no work

done. Several competition entries, including a cantata and a hymn composed for the Paris Exhibition of 1867 were unsuccessful. La Coupe du Roi de Thulé,

his entry for an opera competition, was not placed in the first five;

from the fragments of this score that survive, analysts have discerned

pre-echoes of Carmen. On 28 February 1869 the Roma symphony was performed at the Cirque Napoléon, under Jules Pasdeloup. Afterwards Bizet informed Galabert that on the basis of proportionate applause, hisses and catcalls, the work was a success.

Not long after Fromental Halévy's death in 1862, Bizet had been approached on behalf of Mme. Halévy about completing his old tutor's unfinished opera Noé. Although no action was taken at that time, Bizet remained on friendly terms with the Halévy family. Fromental had left two daughters; the elder, Esther, died in 1864, an event which so traumatized Mme. Halévy that she could not tolerate the company of her younger daughter Geneviève, who from the age of 15 lived with other family members. It is unclear when she and Bizet became emotionally attached, but in October 1867 he informed Galabert: "I have met an adorable girl whom I love! In two years she will be my wife!". The pair became engaged, although the Halévy family initially disallowed the match. According to Bizet they considered him an unsuitable catch: "penniless, left wing, anti - religious and Bohemian", which Dean observes are odd grounds of objection from "a family bristling with artists and eccentrics". By summer 1869 their objections had been overcome, and the wedding took place on 3 June 1869. Ludovic Halévy wrote in his journal: "Bizet has spirit and talent. He should succeed".

As a belated homage to his late father - in - law, Bizet took up the Noé manuscript and completed it. Parts of his moribund Vasco da Gama and Ivan IV

were incorporated into the score, but a projected production at the

Théâtre Lyrique failed to materialize when Carvalho's company finally

went bankrupt, and Noé remained unperformed until 1885.

Bizet's marriage was initially happy, but was affected by

Geneviève's nervous instability (inherited from both her

parents), her difficult relations with her mother and by Mme. Halévy's interference in the couple's affairs. Despite this, Bizet kept on good terms with his mother - in - law and maintained an extensive correspondence with her.

In the year following the marriage he considered plans for at least

half a dozen new operas, and began to sketch the music for two of them: Clarissa Harlowe based on Samuel Richardson's novel Clarissa, and Grisélidis with a libretto from Victorien Sardou. However, his progress on these projects was brought to a halt in July 1870, with the outbreak of the Franco - Prussian War.

After a series of perceived provocations from Prussia, culminating in the offer of the Spanish crown to the Prussian Prince Leopold of Hohenzollern, the French emperor Napoleon III declared war on 15 July 1870. Initially this step was supported by an outbreak of patriotic fervor and confident expectations of victory. Bizet, along with other composers and artists, joined the National Guard and began training. He was critical of the antiquated equipment with which he was supposed to fight; his unit's guns, he said, were more dangerous to themselves than to the enemy. The national mood was soon depressed by news of successive reverses; at Sedan on 2 September the French armies suffered an overwhelming defeat; Napoleon was captured and deposed, and the Second Empire came to a sudden end.

Bizet greeted with enthusiasm the proclamation in Paris of the Third Republic. The new government did not sue for peace, and by 17 September the Prussian armies had surrounded Paris. Unlike Gounod, who fled to England, Bizet rejected opportunities to leave the besieged city: "I can't leave Paris! It's impossible! It would be quite simply an act of cowardice", he wrote to Mme Halévy. Life in the city became frugal and harsh, although by October there were efforts to re-establish normality. Pasdeloup resumed his regular Sunday concerts, and on 5 November the Opéra reopened with excerpts from works by Gluck, Rossini and Meyerbeer.

An armistice was signed on 26 January 1871, but the departure of the Prussian troops from Paris in March presaged a period of confusion and civil disturbance. Following an uprising, the city's municipal authority was taken over by dissidents who established the Paris Commune. Bizet decided that he was no longer safe in the city, and he and Geneviève escaped to Compiègne. Later they moved to Le Vésinet where they sat out the two months of the Commune, within hearing distance of the gunfire that resounded as government troops gradually crushed the uprising: "The cannons are rumbling with unbelievable violence", Bizet wrote to his mother - in - law on 12 May. By 25 May hostilities had ended; it was later estimated that during the Commune and in the reprisals which followed, around 25,000 lives had been lost.

As life in Paris returned to normal, in June 1871 Bizet's appointment as

chorus master at The Opéra was seemingly confirmed by its director, Émile Perrin.

Bizet was due to begin his duties in October, but on 1 November the

post was assumed by Hector Salomon. In her biography of Bizet, Mina

Curtiss surmises that he either resigned or refused to take up the

position as a protest against what he thought was the director's

unjustified closing of Ernest Reyer's opera Erostrate after only two performances. Bizet resumed work on Clarissa Harlowe and Grisélidis,

but plans for the latter to be staged at the Opéra - Comique fell

through, and neither work was finished; only fragments of their music

survive. Bizet's other completed works in 1871 were the piano duet entitled Jeux d'enfants, and a one act opera, Djamileh,

which opened at the Opéra - Comique in May 1872. It was poorly staged and

incompetently sung; at one point the leading singer missed 32 bars of

music. It closed after 11 performances, not to be heard again until

1938. On 10 July Geneviève gave birth to the couple's only child, a son, Jacques.

Bizet's next major assignment came from Carvalho, now managing Paris's Vaudeville theater, who wanted incidental music for Alphonse Daudet's play L'Arlésienne. When the play opened on 1 October the music was dismissed by critics as too complex for popular taste. However, encouraged by Reyer and Massenet, Bizet fashioned a four movement suite from the music, which was performed under Pasdeloup on 10 November to an enthusiastic reception. In the winter of 1872 – 73, Bizet supervised preparations for a revival of the still absent Gounod's Roméo et Juliette at the Opéra - Comique. Relations between the two had been cool for some years, but Bizet responded positively to his former mentor's request for help, writing: "You were the beginning of my life as an artist. I spring from you".

In June 1872 Bizet informed Galabert: "I have just been ordered to

compose three acts for the Opéra - Comique. [Henri] Meilhac and [Ludovic]

Halévy are doing my piece". The subject chosen for this project was Prosper Mérimée's short novel Carmen. Bizet began the music in the summer of 1873, but the Opéra - Comique's

management was concerned about the suitability of this risqué story for a

theater that generally provided wholesome entertainment, and work was

suspended. Bizet then began composing Don Rodrigue, an adaptation of the El Cid story by Louis Gallet and Édouard Blau. He played a piano version to a select audience that included the Opéra's principal baritone Jean - Baptiste Faure, hoping that the singer's approval might influence the directors of the Opéra to stage the work.

However, on the night of 28 – 29 October, the Opéra burned to the

ground; the directors, amid other pressing concerns, set Don Rodrigue aside. It was never completed; Bizet later adapted a theme from its final act as the basis of his 1875 overture, Patrie.

Adolphe de Leuven, the co-director of the Opéra - Comique most bitterly opposed to the Carmen project, resigned early in 1874, removing the main barrier to the work's production. Bizet finished the score during the summer, and was pleased with the outcome: "I have written a work that is all clarity and vivacity, full of color and melody". The renowned mezzo - soprano Célestine Galli - Marié (known professionally as "Galli - Marié"), was engaged to sing the title role. According to Dean she was as delighted by the part as Bizet was by her suitability for it. There were rumors that he and the singer pursued a brief affair; his relations with Geneviève were strained at this time, and they lived apart for several months.

When rehearsals began in October 1874 the orchestra had difficulties with the score, finding some parts unplayable. The chorus likewise declared some of their music impossible to sing, and were dismayed by having to act as individuals, smoking and fighting onstage rather than merely standing in line. Bizet also had to counter further attempts at the Opéra - Comique to modify parts of the action which they deemed improper. Only when the leading singers threatened to withdraw from the production did the management give way. Resolving these issues delayed the first night until 3 March 1875 on which morning, by chance, Bizet's appointment as a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor was announced.

Among leading musical figures at the premiere were Jules Massenet, Camille Saint - Saëns and Charles Gounod. Geneviève, suffering from an abscess in her right eye, was unable to be present. The opera's first performance extended to four - and - a - half hours; the final act did not begin until after midnight.

Afterwards, Massenet and Saint - Saëns were congratulatory, Gounod less

so. According to one account he accused Bizet of plagiarism: "Georges

has robbed me! Take the Spanish airs and mine out of the score and there

remains nothing to Bizet's credit but the sauce that masks the fish".

Much of the press comment was negative, expressing consternation that

the heroine was an amoral seductress rather than a woman of virtue. Galli - Marié's performance was described by one critic as "the very incarnation of vice". Others complained of a lack of melody, and made unfavorable comparisons with the traditional Opéra - Comique fare of Auber and Boieldieu. Léon Escudier in L'Art Musical called the music "dull and obscure ... the ear grows weary of waiting for the cadence that never comes". There was, however, praise from the poet Théodore de Banville, who applauded Bizet for presenting a drama with real men and women instead of the usual Opéra - Comique "puppets". The public's reaction was lukewarm, and Bizet soon became convinced of its failure: "I foresee a definite and hopeless flop".

For most of his life Bizet had suffered from a recurrent throat complaint. A heavy smoker, he may have further undermined his health by overwork during the mid 1860s, when he toiled over publishers' transcriptions for up to 16 hours a day. In 1868 he informed Galabert that he had been very ill with abscesses in the windpipe: "I suffered like a dog". In 1871, and again in 1874 while completing Carmen, he had been disabled by severe bouts of what he described as "throat angina", and suffered a further attack in late March 1875. At that time, depressed by the evident failure of Carmen, Bizet was slow to recover and fell ill again in May. At the end of the month he went to his holiday home at Bougival and, feeling a little better, went for a swim in the Seine. On the next day, 1 June, he was afflicted by high fever and pain, which was followed by an apparent heart attack. He seemed temporarily to recover, but in the early hours of 3 June, his wedding anniversary, he suffered a fatal second attack.

The suddenness of Bizet's death, and awareness of his depressed mental state, fueled rumors of suicide. Although the exact cause of death was never settled with certainty, physicians discounted such theories and eventually determined the cause as "a cardiac complication of acute articular rheumatism". News of the death stunned Paris's musical world; as Galli - Marié was too upset to appear, that evening's performance of Carmen was canceled and replaced with Boieldieu's La Dame blanche.

At the funeral on 5 June at the Église de la Sainte - Trinité in Monmartre, more than 4,000 people were present. Adolphe Bizet led the mourners, who included Gounod, Thomas, Ludovic Halévy, Léon Halévy and Massenet. An orchestra under Pasdeloup played Patrie, and the organist improvised a fantasy on themes from Carmen. At the burial which followed at the Père Lachaise Cemetery, Gounod gave the eulogy. He said that Bizet had been struck down just as he was becoming recognized as a true artist. Towards the end of his address Gounod broke down, and was unable to deliver his final peroration. After a special performance of Carmen at the Opéra - Comique that night, the press which had almost universally condemned the piece three months earlier now declared Bizet a master.

Bizet's earliest compositions, chiefly songs and keyboard pieces written

as exercises, give early indications of his emergent power and his

gifts as a melodist. Dean sees evidence in the piano work Romance sans parole, written before 1854, of "the conjunction of melody, rhythm and accompaniment" that is characteristic of Bizet's mature works. Bizet's first orchestral piece was an overture written in 1855 in the manner of Rossini's Guillaume Tell. Critics have found it unremarkable, but the Symphony in C of the same year has been warmly praised by later commentators who have made favorable comparisons with Mozart and Schubert. In Dean's view the symphony has "few rivals and perhaps no superior in the work of any composer of such youth". The critic Ernest Newman

suggests that Bizet may at this time thought that his future lay in the

field of instrumental music, before an "inner voice" (and the realities

of the French musical world) turned him towards the stage.

After his early Symphony in C, Bizet's purely orchestral output is sparse. The Roma symphony over which he labored for more than eight years compares poorly, in Dean's view, with its juvenile predecessor. The work, says Dean, owes something to Gounod, and contains passages that recall Weber and Mendelssohn. However, Dean contends that the work suffers from poor organization and an excess of pretentious music; he calls it a "misfire". Bizet's other mature orchestral work, the overture Patrie, is similarly dismissed: "an awful warning of the danger of confusing art with patriotism". The musicologist Hugh Macdonald argues that Bizet's best orchestral music is found in the suites that he derived respectively from the piano work Jeux d'enfants and the incidental music for L'Arlésienne. In these he demonstrates a maturity of style that, had he lived longer, might have been the basis for future great orchestral works.

Bizet's piano works have not entered the concert pianist's

repertoire, and are generally too difficult for amateurs to attempt. An

exception is the set of 12 pieces evoking the world of children's games,

Jeux d'enfants, written for four hands. Here, Bizet avoided the virtuoso passages which tend to dominate his solo works. The earlier solo pieces bear the influence of Chopin; later works, such as the Variations Chromatiques and the Chasse Fantastique, owe more to Liszt.

Most of Bizet's songs were written in the period 1866 – 68. Dean defines

the main weaknesses in these songs as an unimaginative repetition of the

same music for each verse, and a tendency to write for the orchestra

rather than the voice. Much of Bizet's larger scale vocal music is lost; the early Te Deum,

which survives in full, is rejected by Dean as "a wretched work [that]

merely illustrates Bizet's unfitness to write religious music."

Bizet's early one act opera Le docteur Miracle provides the first clear signs of his promise in this genre, its sparkling music including, according to Dean, "many happy touches of parody, scoring and comic characterization". Newman perceives evidence of Bizet's later achievements in many of his earliest works: "[A]gain and again we light upon some touch or other in them that only a musician with a dramatic root of the matter in him could have achieved." Until Carmen, however, Bizet was not essentially an innovator in the musical theatre. He wrote most of his operas in the traditions of Italian and French opera established by such as Donizetti, Rossini, Berlioz, Gounod and Thomas. Macdonald suggests that, technically, he surpassed all of these, with a feeling for the human voice that compares with that of Mozart.

In Don Procopio Bizet followed the stock devices of Italian opera as typified by Donizetti in Don Pasquale, a work which it closely resembles. However, the familiar idiom is interspersed with original touches in which Bizet's fingerprints emerge unmistakably. In his first significant opera, Les pêcheurs de perles, Bizet was hampered by a dull libretto and a laborious plot; nevertheless, the music in Dean's view rises at times "far above the level of contemporary French opera". Its many original flourishes include the introduction to the cavatina Comme autrefois dans la nuit sombre played by two French horns over a cello background, an effect which in the words of analyst Hervé Lacombe, "resonates in the memory like a fanfare lost in a distant forest". While the music of Les pêcheurs is atmospheric and deeply evocative of the opera's Eastern setting, in La jolie fille de Perth Bizet made no attempt to introduce Scottish colour or mood, though the scoring includes highly imaginative touches such as a separate band of woodwind and strings during the opera's Act III seduction scene.

From Bizet's unfinished works, Macdonald highlights La coupe du roi de Thulé as giving clear signs of the power that would reach a pinnacle in Carmen, and suggests that had Clarissa Harlowe and Grisélidis been completed, Bizet's legacy would have been "infinitely richer". As Bizet moved away from the accepted musical conventions of French opera he encountered critical hostility. In the case of Djamileh, the accusation of "Wagnerism" was raised again, as audiences struggled to understand the score's originality; many found the music pretentious and monotonous, lacking in both rhythm and melody. By contrast, modern critical opinion as expressed by Macdonald is that Djamileh is "a truly enchanting piece, full of inventive touches, especially of chromatic color."

Ralph P. Locke, in his study of Carmen's origins, draws attention to Bizet's successful evocation of Andalusian Spain. Grout, in his History of Western Music,

praises the music's extraordinary rhythmic and melodic vitality, and

Bizet's ability to obtain the maximum dramatic effect in the most

economical fashion. Among the opera's early champions were Tchaikovsky, Brahms, and particularly Wagner, who commented: "Here, thank God, at last for a change is somebody with ideas in his head." Another champion of the work was Friedrich Nietzsche,

who claimed to know it by heart; "It is music that makes no pretensions

to depth, but it is delightful in its simplicity, so unaffected and

sincere". By broad consent, Carmen represents the fulfillment of Bizet's development as a master of music drama, and the culmination of the genre of opéra comique.

After Bizet's death many of his manuscripts were lost; works were revised by other hands, and published in these unauthorized versions so that it is often difficult to establish what is authentic Bizet. Even Carmen was altered into grand opera format by the replacement of its dialogue with recitatives written by Guiraud, and by other amendments to the score. The music world did not immediately acknowledge Bizet as a master and, apart from Carmen and the L'Arlésienne suite, few of his works were performed in the years immediately following his death. However, the 20th century saw an increase of interest. Don Procopio was revived in Monte Carlo in 1906; An Italian version of Les pêcheurs de perles was performed at the Metropolitan Opera in New York on 13 November 1916, with Caruso in the leading tenor role; it has since become a staple at many opera houses. After its first performance in Switzerland in 1935, the Symphony in C entered the concert repertory, and has been recorded by, among many others, Sir Thomas Beecham. Excerpts from La coupe du roi de Thulé, edited by Winton Dean, were broadcast by the BBC on 12 July 1955, and Le docteur Miracle was revived in London on 8 December 1957 by the Park Lane Group. Items from Vasco da Gama and Ivan IV have been recorded, as have numerous songs and the complete piano music. Carmen, after its lukewarm initial Paris run of 45 performances, became a worldwide popular success after performances in Vienna (1875) and London (1878). It has been hailed as the first opera of the verismo school, in which sordid and brutal subjects are emphasised, with art reflecting life — "not idealised life but life as actually lived."

Schonberg surmises that had Bizet lived, he might have revolutionised French opera; as it is, verismo was taken up mainly by Italians, notably Puccini who, according to Dean, developed the idea "till it became threadbare". Bizet founded no specific school, though Dean names Chabrier and Ravel as composers influenced by him. Dean also suggests that a fascination with Bizet's tragic heroes — Frédéri in L'Arlésienne, José in Carmen — is reflected in Tchaikovsky's late symphonies, particularly the B minor "Pathetique". Macdonald writes that Bizet's legacy is limited by the shortness of his life and by the false starts and lack of focus that persisted until his final five years. "The spectacle of great works unwritten either because Bizet had other distractions, or because no one asked him to write them, or because of his premature death, is infinitely dispiriting, yet the brilliance and the individuality of his best music is unmistakable. It has greatly enriched a period of French music already rich in composers of talent and distinction".

Of Bizet's family circle, his father Adolphe died in 1886. Bizet's son Jacques committed suicide in 1922 after an unhappy love affair. Jean Reiter, Bizet's elder son, had a successful career as press director of Le Temps, became an Officer of the Legion of Honor, and died in 1939 at the age of 77. In 1886 Geneviève married Émile Straus, a rich lawyer; she became a famous Parisian society hostess and a close friend of, among others, Marcel Proust. She showed little interest in her first husband's musical legacy, made no effort to catalogue Bizet's manuscripts and gave many away as souvenirs. She died in 1926; in her will she established a fund for a Georges Bizet prize, to be awarded annually to a composer under 40 who had "produced a remarkable work within the previous five years". Winners of the prize include Tony Aubin, Jean - Michel Damase, Henri Dutilleux and Jean Martinon.

In 1930 composer and biographer Marc Delmas published a biography of Bizet entitled Georges Bizet, 1838 - 1875.

Max Christian Friedrich Bruch (6 January 1838 – 2 October 1920), also known as Max Karl August Bruch, was a German Romantic composer and conductor who wrote over 200 works, including three violin concertos, the first of which has become a staple of the violin repertoire.

Bruch was born in Cologne, Rhine Province, where he received his early musical training under the composer and pianist Ferdinand Hiller, to whom Robert Schumann dedicated his piano concerto. Ignaz Moscheles recognized his aptitude. Bruch had a long career as a teacher, conductor and composer, moving among musical posts in Germany: Mannheim (1862 - 1864), Koblenz (1865 - 1867), Sondershausen, (1867 - 1870), Berlin (1870 - 1872), and Bonn, where he spent 1873 - 78 working privately. At the height of his reputation he spent three seasons as conductor of the Liverpool Philharmonic Society (1880 - 83). There he met his wife, Clara Tuczek. He taught composition at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik from 1890 until his retirement in 1910. Bruch died in his house in Berlin - Friedenau.

His complex and well structured works, in the German romantic musical tradition, placed him in the camp of Romantic classicism exemplified by Johannes Brahms, rather than the opposing "New Music" of Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner. In his time, he was known primarily as a choral composer.

His Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 26 (1866) is one of the most popular Romantic violin concertos. It uses several techniques from Felix Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto in E minor. These include the linking of movements, and a departure from the customary orchestral exposition and rigid form of earlier concertos. It is a singularly melodic composition which many critics have said represents the apex of the romantic tradition.

Other pieces which are also well known and widely played include the Scottish Fantasy for violin and orchestra, which includes an arrangement of the tune "Hey Tuttie Tatie", best known for its use in the song Scots Wha Hae by Robert Burns. Bruch also wrote Kol Nidrei, Op. 47, a popular work for cello and orchestra (its subtitle is "Adagio on Hebrew Melodies for Violoncello and Orchestra"). This piece was based on Hebrew melodies, principally the melody of the Kol Nidre incantation from the Jewish Yom Kippur service, which gives the piece its name.

The success of this work has made many assume that Bruch himself had Jewish ancestry - indeed, under the National Socialist Party his music ceased to be programmed because of the possibility of his being a Jew; as a result of this, his music was completely forgotten in German speaking countries - but there is no evidence for his being Jewish. As far as can be ascertained, none of his ancestors were Jews, and Bruch himself was raised Rhenish - Catholic.

He wrote the Concerto in A flat minor for Two Pianos and Orchestra, Op. 88a, in 1912 for the American duo pianists Rose and Ottilie Sutro, but they never played the original version; they only ever played the work twice, in two different versions of their own. The score was withdrawn in 1917 and discovered only after Ottilie Sutro's death in 1970. The Sutro sisters also had a major part to play in the fate of the manuscript of the Violin Concerto No. 1. Bruch sent it to them to be sold in the United States, but they kept it and sold it for profit themselves.

Other works include two other concerti for violin and orchestra, No. 2 in D minor and No. 3 in D minor (which Bruch himself regarded as at least as fine as the famous first); and a Concerto for Clarinet, Viola and Orchestra. There are also 3 symphonies, which, while not displaying any originality in form or structure, nevertheless show Bruch at his best as a composer of fine melodic talent and a gift for orchestration, firmly in the tradition of the Romantics. He wrote a number of chamber works, including a set of eight pieces for piano, clarinet, and viola; and a string octet.

The violinists Joseph Joachim and Willy Hess advised Bruch on composing for strings, and Hess performed the premieres of a number of works by Bruch, including the Concert Piece for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 84, which was composed for him.

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (Russian: Моде́ст Петро́вич Мýсoргский; 21 March [O.S. 9 March] 1839 – 28 March [O.S. 16 March] 1881) was a Russian composer, one of the group known as "The Five". He was an innovator of Russian music in the romantic period. He strove to achieve a uniquely Russian musical identity, often in deliberate defiance of the established conventions of Western music.

Many of his works were inspired by Russian history, Russian folklore, and other nationalist themes. Such works include the opera Boris Godunov, the orchestral tone poem Night on Bald Mountain, and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition.

For many years Mussorgsky's works were mainly known in versions

revised or completed by other composers. Many of his most important

compositions have recently come into their own in their original forms,

and some of the original scores are now also available.

Mussorgsky was born in Karevo, Toropets, Pskov region, Imperial Russia, 400 km (250 mi) south of Saint Petersburg. His wealthy and land owning family, the noble family of Mussorgsky, is reputedly descended from the first Ruthenian ruler, Rurik, through the sovereign princes of Smolensk. At age six Mussorgsky began receiving piano lessons from his mother, herself a trained pianist. His progress was sufficiently rapid that three years later he was able to perform a John Field concerto and works by Franz Liszt for family and friends. At 10, he and his brother were taken to Saint Petersburg to study at the elite Peterschule (St. Peter's School). While there, Modest studied the piano with the noted Anton Gerke. In 1852, the 12 year old Mussorgsky published a piano piece titled "Porte - enseigne Polka" at his father's expense.

Mussorgsky's parents planned the move to Saint Petersburg so that both their sons would renew the family tradition of military service. To this end, Mussorgsky entered the Cadet School of the Guards at age 13. Sharp controversy had arisen over the educational attitudes at the time of both this institute and its director, a General Sutgof. All agreed the Cadet School could be a brutal place, especially for new recruits. More tellingly for Mussorgsky, it was likely where he began his eventual path to alcoholism. According to a former student, singer and composer Nikolai Kompaneisky, Sutgof "was proud when a cadet returned from leave drunk with champagne."

Music remained important to him, however. Sutgof's daughter was also a

pupil of Herke, and Mussorgsky was allowed to attend lessons with her. His skills as a pianist made him much in demand by fellow cadets; for them he would play dances interspersed with his own improvisations.

In 1856 Mussorgsky – who had developed a strong interest in history and

studied German philosophy – successfully graduated from the Cadet

School. Following family tradition he received a commission with the Preobrazhensky Regiment, the foremost regiment of the Russian Imperial Guard.

In October 1856 the 17 year old Mussorgsky met the 22 year old Alexander Borodin while both men served at a military hospital in Saint Petersburg. The two were soon on good terms. Borodin later remembered,

His little uniform was spic and span, close - fitting, his feet turned outwards, his hair smoothed down and greased, his nails perfectly cut, his hands well groomed like a lord's. His manners were elegant, aristocratic: his speech likewise, delivered through somewhat clenched teeth, interspersed with French phrases, rather precious. There was a touch — though very moderate — of foppishness. His politeness and good manners were exceptional. The ladies made a fuss of him. He sat at the piano and, throwing up his hands coquettishly, played with extreme sweetness and grace (etc) extracts from Trovatore, Traviata, and so on, and around him buzzed in chorus: "Charmant, délicieux!" and suchlike. I met Modest Petrovich three or four times at Popov's in this way, both on duty and at the hospital."

More portentous was Mussorgsky's introduction that winter to Alexander Dargomyzhsky, at that time the most important Russian composer after Mikhail Glinka. Dargomyzhsky was impressed with Mussorgsky's pianism. As a result, Mussorgsky became a fixture at Dargomyzhsky's soirées. There, critic Vladimir Stasov later recalled, he began "his true musical life."

Over the next two years at Dargomyzhsky's, Mussorgsky met several figures of importance in Russia's cultural life, among them Stasov, César Cui (a fellow officer), and Mily Balakirev. Balakirev had an especially strong impact. Within days he took it upon himself to help shape Mussorgsky's fate as a composer. He recalled to Stasov, "Because I am not a theorist, I could not teach him harmony (as, for instance Rimsky - Korsakov now teaches it) ... [but] I explained to him the form of compositions, and to do this we played through both Beethoven symphonies [as piano duets] and much else (Schumann, Schubert, Glinka, and others), analyzing the form." Up to this point Mussorgsky had known nothing but piano music; his knowledge of more radical recent music was virtually non - existent. Balakirev started filling these gaps in Mussorgsky's knowledge.

In 1858, within a few months of beginning his studies with Balakirev, Mussorgsky resigned his commission to devote himself entirely to music. He also suffered a painful crisis at this time. This may have had a spiritual component (in a letter to Balakirev the young man referred to "mysticism and cynical thoughts about the Deity"), but its exact nature will probably never be known. In 1859, the 20 year old gained valuable theatrical experience by assisting in a production of Glinka's opera A Life for the Tsar on the Glebovo estate of a former singer and her wealthy husband; he also met Anatoly Lyadov and enjoyed a formative visit to Moscow – after which he professed a love of "everything Russian".

In spite of this epiphany, Mussorgsky's music still leaned more toward foreign models; a four hand piano sonata which he produced in 1860 contains his only movement in sonata form. Nor is any 'nationalistic' impulse easily discernible in the incidental music for Serov's play Oedipus in Athens, on which he worked between the ages of 19 and 22 (and then abandoned unfinished), or in the Intermezzo in modo classico for piano solo (revised and orchestrated in 1867). The latter was the only important piece he composed between December 1860 and August 1863: the reasons for this probably lie in the painful re-emergence of his subjective crisis in 1860 and the purely objective difficulties which resulted from the emancipation of the serfs the following year – as a result of which the family was deprived of half its estate, and Mussorgsky had to spend a good deal of time in Karevo unsuccessfully attempting to stave off their looming impoverishment.

By this time, Mussorgsky had freed himself from the influence of Balakirev and was largely teaching himself. In 1863 he began an opera – Salammbô – on which he worked between 1863 and 1866 before losing interest in the project. During this period he had returned to Saint Petersburg and was supporting himself as a low grade civil servant while living in a six man "commune". In a heady artistic and intellectual atmosphere, he read and discussed a wide range of modern artistic and scientific ideas – including those of the provocative writer Chernyshevsky, known for the bold assertion that, in art, "form and content are opposites". Under such influences he came more and more to embrace the ideal of artistic realism and all that it entailed, whether this concerned the responsibility to depict life "as it is truly lived"; the preoccupation with the lower strata of society; or the rejection of repeating, symmetrical musical forms as insufficiently true to the unrepeating, unpredictable course of "real life".

"Real life" affected Mussorgsky painfully in 1865, when his mother died; it was at this point that the composer had his first serious bout of either alcoholism or dipsomania. The 26 year old was, however, on the point of writing his first realistic songs (including "Hopak" and "Darling Savishna", both of them composed in 1866 and among his first "real" publications the following year). 1867 was also the year in which he finished the original orchestral version of his Night on Bald Mountain (which, however, Balakirev criticized and refused to conduct, with the result that it was never performed during Mussorgsky's lifetime).

Mussorgsky's career as a civil servant was by no means stable or secure:

though he was assigned to various posts and even received a promotion

in these early years, in 1867 he was declared 'supernumerary' –

remaining 'in service', but receiving no wages. Decisive developments

were occurring in his artistic life, however. Although it was in 1867

that Stasov first referred to the 'kuchka'

('The Five') of Russian composers loosely grouped around Balakirev,

Mussorgsky was by then ceasing to seek Balakirev's approval and was

moving closer to the older Alexander Dargomyzhsky .

Since 1866 Dargomïzhsky had been working on his opera The Stone Guest, a version of the Don Juan story with a Pushkin text that he declared would be set "just as it stands, so that the inner truth of the text should not be distorted", and in a manner that abolished the 'unrealistic' division between aria and recitative in favor of a continuous mode of syllabic but lyrically heightened declamation somewhere between the two.

Under the influence of this work (and the ideas of Georg Gottfried Gervinus,

according to whom "the highest natural object of musical imitation is

emotion, and the method of imitating emotion is to mimic speech"),

Mussorgsky in 1868 rapidly set the first eleven scenes of Nikolai Gogol's The Marriage (Zhenitba),

with his priority being to render into music the natural accents and

patterns of the play's naturalistic and deliberately humdrum dialogue.

This work marked an extreme position in Mussorgsky's pursuit of

naturalistic word setting: he abandoned it unorchestrated after reaching

the end of his 'Act 1', and though its characteristically

'Mussorgskyian' declamation is to be heard in all his later vocal music,

the naturalistic mode of vocal writing more and more became merely one

expressive element among many.

A few months after abandoning Zhenitba, the 29 year old Mussorgsky was encouraged to write an opera on the story of Boris Godunov. This he did, assembling and shaping a text from Pushkin's play and Karamzin's history. He completed the large scale score the following year while living with friends and working for the Forestry Department. In 1871, however, the finished opera was rejected for theatrical performance, apparently because of its lack of any 'prima donna' role. Mussorgsky set to work producing a revised and enlarged 'second version'. During the next year, which he spent sharing rooms with Rimsky - Korsakov, he made changes that went beyond those requested by the theatre. In this version the opera was accepted, probably in May 1872, and three excerpts were staged at the Mariinsky Theatre in 1873. It is often asserted that in 1872 the opera was rejected a second time, but no specific evidence for this exists.

By the time of the first production of Boris Godunov in February 1874, Mussorgsky had taken part in the ill fated Mlada project (in the course of which he had made a choral version of his Night on Bald Mountain) and had begun Khovanshchina. Though far from being a critical success – and in spite of receiving only a dozen or so performances – the popular reaction in favor of Boris made this the peak of Mussorgsky's career.

From this peak a pattern of decline becomes increasingly apparent. Already the Balakirev circle was disintegrating. Mussorgsky was especially bitter about this. He wrote to Vladimir Stasov, "[T]he mighty Koocha has degenerated into soulless traitors." In drifting away from his old friends, Mussorgsky had been seen to fall victim to 'fits of madness' that could well have been alcoholism related. His friend Viktor Hartmann had died, and his relative and recent roommate Arseny Golenishchev - Kutuzov (who furnished the poems for the song cycle Sunless and would go on to provide those for the Songs and Dances of Death) had moved away to get married.

While alcoholism was Mussorgsky's personal weakness, it was also a behavior pattern considered typical for those of Mussorgsky's generation who wanted to oppose the establishment and protest through extreme forms of behavior. One contemporary notes, "an intense worship of Bacchus was considered to be almost obligatory for a writer of that period. It was a showing off, a 'pose,' for the best people of the [eighteen-] sixties." Another writes, "Talented people in Russia who love the simple folk cannot but drink." Mussorgsky spent day and night in a Saint Petersburg tavern of low repute, the Maly Yaroslavets, accompanied by other bohemian dropouts. He and his fellow drinkers idealized their alcoholism, perhaps seeing it as ethical and aesthetic opposition. This bravado, however, led to little more than isolation and eventual self - destruction.

For a time Mussorgsky was able to maintain his creative output: his compositions from 1874 include Sunless, the Khovanschina Prelude, and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition (in memory of Hartmann); he also began work on another opera based on Gogol, The Fair at Sorochyntsi (for which he produced another choral version of Night on Bald Mountain).

In the years that followed, Mussorgsky's decline became increasingly steep. Although now part of a new circle of eminent personages that included singers, medical men and actors, he was increasingly unable to resist drinking, and a succession of deaths among his closest associates caused him great pain. At times, however, his alcoholism would seem to be in check, and among the most powerful works composed during his last 6 years are the four Songs and Dances of Death. His civil service career was made more precarious by his frequent 'illnesses' and absences, and he was fortunate to obtain a transfer to a post (in the Office of Government Control) where his music loving superior treated him with great leniency – in 1879 even allowing him to spend 3 months touring 12 cities as a singer's accompanist.

The decline could not be halted, however. In 1880 he was finally dismissed from government service. Aware of his destitution, one group of friends organized a stipend designed to support the completion of Khovanschina; another group organized a similar fund to pay him to complete The Fair at Sorochyntsi. However, neither work was completed (although Khovanschina, in piano score with only two numbers uncomposed, came close to being finished).

In early 1881 a desperate Mussorgsky declared to a friend that there was 'nothing left but begging', and suffered four seizures in rapid succession. Though he found a comfortable room in a good hospital – and for several weeks even appeared to be rallying – the situation was hopeless. Repin painted the famous red nosed portrait in what were to be the last days of the composer's life: a week after his 42nd birthday, he was dead. He was interred at the Tikhvin Cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg.

Mussorgsky, like others of 'The Five', was perceived as extremist by the Emperor and much of his court. This may have been the reason Tsar Alexander III personally crossed off Boris Godunov from the list of proposed pieces for the Imperial Opera in 1888.

Mussorgsky's works, while strikingly novel, are stylistically Romantic and draw heavily on Russian musical themes. He has been the inspiration for many Russian composers, including most notably Dmitri Shostakovich (in his late symphonies) and Sergei Prokofiev (in his operas).

In 1868-9 he composed the opera Boris Godunov, about the life of the Russian tsar, but it was rejected by the Mariinsky Opera. Mussorgsky thus edited the work, making a final version in 1874. The early version is considered darker and more concise than the later version, but also more crude. Nikolai Rimsky - Korsakov re-orchestrated the opera in 1896 and revised it in 1908. The opera has also been revised by other composers, notably Shostakovich, who made two versions, one for film and one for stage.

Khovanshchina, a more obscure opera, was unfinished and unperformed when Mussorgsky died, but it was completed by Rimsky - Korsakov and received its premiere in 1886 in Saint Petersburg. This opera, too, was revised by Shostakovich. The Fair at Sorochyntsi, another opera, was left incomplete at his death but a dance excerpt, the Gopak, is frequently performed.

Mussorgsky's most imaginative and frequently performed work is the cycle of piano pieces describing paintings in sound called Pictures at an Exhibition. This composition, best known through an orchestral arrangement by Maurice Ravel, was written in commemoration of his friend, the architect Viktor Hartmann.

One of Mussorgsky's most striking pieces is the single movement orchestral work Night on Bald Mountain. The work enjoyed broad popular recognition in the 1940s when it was featured, in tandem with Schubert's 'Ave Maria', in the Disney film Fantasia.

Among the composer's other works are a number of songs, including three song cycles: The Nursery (1872), Sunless (1874) and Songs and Dances of Death (1877); plus Mephistopheles' Song of the Flea and many others. Important early recordings of songs by Mussorgsky were made by tenor Vladimir Rosing in the 1920s and 30s. Other recordings have been made by Boris Christoff between 1951 and 1957 and by Sergei Leiferkus in 1993.

Contemporary opinions of Mussorgsky as a composer and person varied from positive to ambiguous to negative. Mussorgsky's eventual supporters, Stasov and Balakirev, initially registered strongly negative impressions of the composer. Stasov wrote Balakirev, in an 1863 letter, "I have no use whatever for Mussorgsky. All in him is flabby and dull. He is, I think, a perfect idiot. Were he left to his own devices and no longer under your strict supervision, he would soon run to seed as all the others have done. There is nothing in him."

Balakirev agreed: "Yes, Mussorgsky is little short of an idiot."

Mixed impressions are recorded by Rimsky - Korsakov and Tchaikovsky, colleagues of Mussorgsky who, unlike him, made their living as composers. Both praised his talent while expressing disappointment with his technique. About Mussorgsky's scores Rimsky - Korsakov wrote, "They were very defective, teeming with clumsy, disconnected harmonies, shocking part - writing, amazingly illogical modulations or intolerably long stretches without ever a modulation, and bad scoring. ...what is needed is an edition for practical and artistic purposes, suitable for performances and for those who wish to admire Mussorgsky's genius, not to study his idiosyncrasies and sins against art."

Rimsky - Korsakov's own editions of Mussorgsky's works met with some criticism of their own. Rimsky - Korsakov's student, Anatoly Lyadov, found them to be lacking, writing "It is easy enough to correct Mussorgsky's irregularities. The only trouble is that when this is done, the character and originality of the music are done away with, and the composer's individuality vanishes."

Tchaikovsky, in a letter to his patroness Nadezhda von Meck was also critical of Mussorgsky: "Mussorgsky you very rightly call a hopeless case. In talent he is perhaps superior to all the [other members of The Five], but his nature is narrow minded, devoid of any urge towards self perfection, blindly believing in the ridiculous theories of his circle and in his own genius. In addition, he has a certain base side to his nature which likes coarseness, uncouthness, roughness.... He flaunts ... his illiteracy, takes pride in his ignorance, mucks along anyhow, blindly believing in the infallibility of his genius. Yet he has flashes of talent which are, moreover, not devoid of originality."

Not all of the criticism of Mussorgsky was negative. In a letter to Pauline Viardot, Ivan Turgenev recorded his impressions of a concert he attended in which he met Mussorgsky and heard two of his songs and excerpts from Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina): "Today I was invited to have dinner in old Petrov's house: I gave him a copy of your song, which pleased him greatly [...] Petrov still admires you as enthusiastically as in the past. In his drawing room there's a bust of you, crowned with laurels, which still bears a strong resemblance to you. I also met his wife (the contralto) [Anna Vorobyova - Petrova, who created the role of Vanya in Glinka's A Life for the Tsar]. She is sixty years old... After dinner she sang two quite original and touching romances by Musorgsky (the author of Boris Godunov, who was also present), in a voice that is still young and charming and has a very expressive timbre. She sang them wonderfully! I was moved to tears, I assure you. Then Mussorgsky played for us and sang, with a rather hoarse voice, some excerpts from his opera and the other one that he is composing now – and the music seemed to me very characteristic and interesting, upon my honor! Old Petrov sang the role of the old profligate and vagabond monk [Varlaam's song about Ivan the Terrible] – it was splendid! I am starting to believe that there really is a future in all of this. Outwardly, Mussorgsky reminds one of Glinka – it is just that his nose is all red (unfortunately, he is an alcoholic), he has pale but beautiful eyes, and fine lips which are squeezed into a fat face with flabby cheeks. I liked him: he is very natural and unaffected, and does not put on any airs. He played us the introduction to his second opera [Khovanshchina]. It is a bit Wagnerian, but full of feeling and beautiful. Forward, forward! Russian artists!!"

Western perceptions of Mussorgsky changed with the European premiere of Boris Godunov in 1908. Before the premiere, he was regarded as an eccentric in the west. Critic Edward Dannreuther, wrote, in the 1905 edition of The Oxford History of Music, "Mussorgsky, in his vocal efforts, appears wilfully eccentric. His style impresses the Western ear as barbarously ugly."

However, after the premiere, views on Mussorgsky's music changed drastically. Gerald Abraham, a musicologist, and an authority on Mussorgsky: "As a musical translator of words and all that can be expressed in words, of psychological states, and even physical movement, he is unsurpassed; as an absolute musician he was hopelessly limited, with remarkably little ability to construct pure music or even a purely musical texture."