<Back to Index>

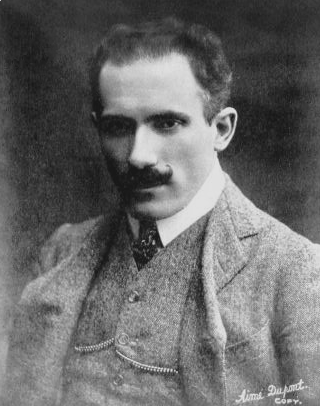

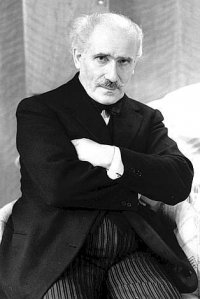

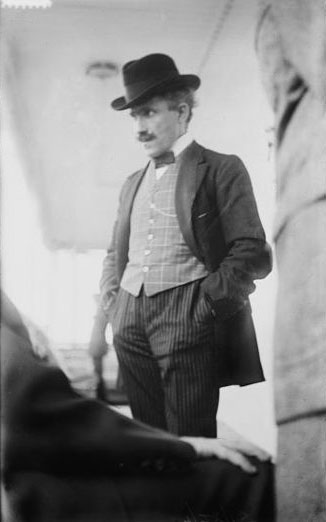

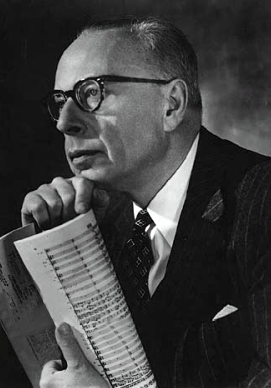

- Conductor Arturo Toscanini, 1867

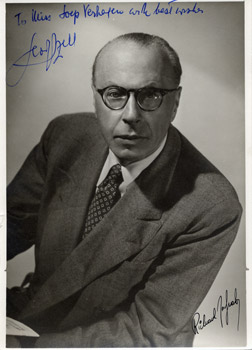

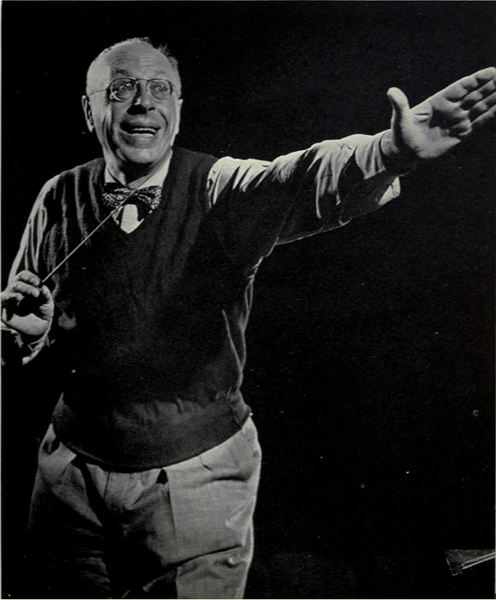

- Conductor and Composer George Szell, 1897

PAGE SPONSOR

Arturo Toscanini (March 25, 1867 – January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. One of the most acclaimed musicians of the late 19th and 20th century, he was renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orchestral detail and sonority, and his photographic memory. As music director of the NBC Symphony Orchestra he became a household name (especially in the U.S.) through his radio and television broadcasts and many recordings of the operatic and symphonic repertoire.

Toscanini was born in Parma, Emilia - Romagna, and won a scholarship to the local music conservatory, where he studied the cello. He joined the orchestra of an opera company, with which he toured South America in 1886. While presenting Aida in Rio de Janeiro, Leopoldo Miguez, the locally hired conductor, reached the summit of a two month escalating conflict with the performers due to his rather poor command of the work, to the point that the singers went on strike and forced the company's general manager to seek a substitute conductor. Carlo Superti and Aristide Venturi tried unsuccessfully to finish the work. In desperation, the singers suggested the name of their assistant Chorus Master, who knew the whole opera from memory. Although he had no conducting experience, Toscanini was eventually convinced by the musicians to take up the baton at 9:15 P.M., and led a performance of the two - and - a - half hour opera. The public was taken by surprise, at first by the youth and sheer aplomb of this unknown conductor, then by his solid mastery. The result was astounding acclaim. For the rest of that season Toscanini conducted eighteen operas, all with absolute success. Thus began his career as a conductor, at age 19.

Upon returning to Italy, Toscanini set out on a dual path for some

time. He continued to conduct, his first appearance in Italy being at

the Teatro Carignano in Turin, on November 4, 1886, in the world premiere of the revised version of Alfredo Catalani's Edmea (it had had its premiere in its original form at La Scala, Milan,

on 27 February of that year). This was the beginning of Toscanini's

life long friendship and championing of Catalani; he even named his

first daughter Wally after the heroine of Catalani's opera La Wally. However, he also returned to his chair in the cello section, and participated as cellist in the world premiere of Verdi's Otello (La Scala, Milan,

1887) under the composer's supervision. Verdi, who habitually

complained that conductors never seemed interested in directing his

scores the way he had written them, was impressed by reports from Arrigo Boito

about Toscanini's ability to interpret his scores. The composer was

also impressed when Toscanini consulted him personally about the Te

Deum, suggesting an allargando

where it was not set out in the score. Verdi said that he had left it

out for fear that "certain interpreters would have exaggerated the

marking".

Gradually the young musician's reputation as an operatic conductor of unusual authority and skill supplanted his cello career. In the following decade he consolidated his career in Italy, entrusted with the world premieres of Puccini's La bohčme and Leoncavallo's Pagliacci. In 1896, Toscanini conducted his first symphonic concert (in Turin, with works by Schubert, Brahms, Tchaikovsky and Wagner). He exhibited a considerable capacity for hard work: in 1898 he conducted 43 concerts in Turin. By 1898 he was principal conductor at La Scala, where he remained until 1908, returning as Music Director, 1921 - 1929. He took the Scala Orchestra to the United States on a concert tour in 1920 - 21; it was during that tour that Toscanini made his first recordings (for the Victor Talking Machine Company).

Outside of Europe, he conducted at the Metropolitan Opera in New York (1908 – 1915) as well as the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (1926 – 1936). He toured Europe with the New York Philharmonic in 1930; he and the musicians were acclaimed by critics and audiences wherever they went. Toscanini was the first non - German conductor to appear at Bayreuth (1930 – 1931), and the New York Philharmonic was the first non - German orchestra to play there. In the 1930s he conducted at the Salzburg Festival (1934 – 1937) and at the inaugural concert in 1936 of the Palestine Orchestra (later renamed the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra) in Tel Aviv, and later performed with them in Jerusalem, Haifa, Cairo and Alexandria.

During his career, Toscanini worked with such legendary artists as

Enrico Caruso, Feodor Chaliapin, Ezio Pinza, Jussi Björling and

Geraldine Farrar. Although he also worked with Wagnerian heldentenor

Lauritz Melchior, he would not work with Melchior's frequent partner

Kirsten Flagstad after her political sympathies became suspect during

World War II; it was Helen Traubel who sang with Melchior instead of

Flagstad at the Toscanini concerts.

In 1919, Toscanini ran unsuccessfully as a Fascist parliamentary candidate in Milan. He had been called "the greatest conductor in the world" by Fascist leader Benito Mussolini. However, he became disillusioned with fascism and repeatedly defied the Italian dictator after the latter's ascent to power in 1922. He refused to display Mussolini's photograph or conduct the Fascist anthem Giovinezza at La Scala. He raged to a friend, "If I were capable of killing a man, I would kill Mussolini."

At a memorial concert for Italian composer Giuseppe Martucci on May 14, 1931 at the Teatro Comunale in Bologna, he was ordered to begin by playing Giovinezza but he refused even though the fascist foreign minister Galeazzo Ciano

was present in the audience. Afterwards he was, in his own words,

"attacked, injured and repeatedly hit in the face" by a group of blackshirts. Mussolini, incensed by the conductor's refusal, had his phone tapped,

placed him under constant surveillance and took away his passport. The

passport was returned only after a world outcry over Toscanini's

treatment.

On the outbreak of the Second World War, Toscanini left Italy. He would

return seven years later to conduct a concert at the restored La Scala

Opera House, which was destroyed by bombs during the war.

Toscanini returned to the United States where the NBC Symphony Orchestra was created for him in 1937. He conducted his first NBC broadcast concert on December 25, 1937, in NBC Studio 8-H in New York City's Rockefeller Center. The acoustics of the specially built studio were very dry; some remodeling in 1939 added a bit more reverberation. (In 1950, the studio was further remodeled for television productions; today it is used by NBC for Saturday Night Live. In 1980, it was used by Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in a series of special televised NBC concerts called "Live From Studio 8H", the first one being a tribute to Toscanini, punctuated by clips from his television concerts.)

The NBC broadcasts were preserved on large transcription discs, recorded at both 78 rpm and 33 1/3 rpm, until NBC began using magnetic tape in 1947. NBC used special RCA high fidelity microphones both for the broadcasts and for recording them; these microphones can be seen in some photographs of Toscanini and the orchestra. Some of Toscanini's recording sessions for RCA Victor were mastered on sound film in a process developed about 1941, as detailed by RCA producer Charles O'Connell in his memoirs, On and Off The Record. In addition, hundreds of hours of Toscanini's rehearsals with the NBC were preserved and are now housed in the Toscanini Legacy archive at The New York Public Library.

Toscanini was often criticized for neglecting American music; however, on November 5, 1938, he conducted the world premieres of two orchestral works by Samuel Barber, Adagio for Strings and Essay for Orchestra. In 1945, he led the orchestra in recording sessions of the Grand Canyon Suite by Ferde Grofé in Carnegie Hall (supervised by Grofé) and An American in Paris by George Gershwin in NBC's Studio 8-H. Both works had earlier been performed in broadcast concerts. He also conducted broadcast performances of Copland's El Salón México; Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue with soloists Earl Wild and Benny Goodman and Piano Concerto in F with pianist Oscar Levant; and music by other American composers, including marches of John Philip Sousa. He even wrote his own orchestral arrangement of The Star - Spangled Banner, which was incorporated into the NBC Symphony's performances of Verdi's Hymn of the Nations. (Earlier, while music director of the New York Philharmonic, he conducted music by Abram Chasins, Bernard Wagenaar, and Howard Hanson.)

In 1940, Toscanini took the orchestra on a "goodwill" tour of South America. Later that year, Toscanini had a disagreement with NBC management over their use of his musicians in other NBC broadcasts. This, among other reasons, resulted in a letter which Toscanini wrote on March 10, 1941 to RCA's David Sarnoff. He stated that he now wished "to withdraw from the militant scene of Art" and thus declined to sign a new contract for the up-coming winter season, but left the door open for an eventual return "if my state of mind, health and rest will be improved enough". So Leopold Stokowski was engaged on a three year contract instead and served as the NBC Symphony's music director from 1941 until 1944. Toscanini's state of mind soon underwent a change and he returned as Stokowski's co-conductor for the latter's second and third seasons resuming full control in 1944.

One of the more remarkable broadcasts was in July 1942, when Toscanini conducted the American premiere of Dmitri Shostakovich's Symphony No. 7. Due to World War II, the score was microfilmed in the Soviet Union and brought by courier to the United States. Stokowski had previously given the US premieres of Shostakovich's 1st, 3rd and 6th Symphonies in Philadelphia, and in December 1941 urged NBC to obtain the score of the 7th as he wanted to conduct its premiere as well. But Toscanini coveted this for himself and there were a number of remarkable letters between the two conductors (reproduced by Harvey Sachs in his biography) before Stokowski agreed to let Toscanini have the privilege of conducting the first performance. Unfortunately for New York listeners, a major thunderstorm virtually obliterated the NBC radio signals there, but the performance was heard elsewhere and preserved on transcription discs. It was later issued by RCA Victor in the 1967 centennial boxed set tribute to Toscanini, which included a number of NBC broadcasts never released on discs. In Testimony Shostakovich himself expressed a dislike for the performance, after he heard a recording of the broadcast. In Toscanini's later years the conductor expressed dislike for the work and amazement that he had actually conducted it.

In the summer of 1950, Toscanini led the orchestra on an extensive transcontinental tour. It was during that tour that the well known photograph of Toscanini riding the ski lift at Sun Valley, Idaho, was taken. Toscanini and the musicians traveled on a special train chartered by NBC.

The NBC concerts continued in Studio 8-H until the fall of 1950. They were then held in Carnegie Hall, where many of the orchestra's recording sessions had been held, due to the dry acoustics of Studio 8-H. The final broadcast performance, an all Wagner program, took place on April 4, 1954, in Carnegie Hall. During this concert Toscanini suffered a memory lapse reportedly caused by a transient ischemic attack, although some have attributed the lapse to having been secretly informed that NBC intended to end the broadcasts and disband the NBC orchestra. He never conducted live in public again. That June, he participated in his final recording sessions, remaking portions of two Verdi operas so they could be commercially released. Toscanini was 87 years old when he retired. After his retirement, the NBC Symphony was reorganized as the Symphony of the Air, making regular performances and recordings, until it was disbanded in 1963.

On radio, he conducted seven complete operas, including La bohčme, La traviata, and Otello,

all of which were eventually released on records and CD, thus enabling

the modern listening public to have at least some idea of what an opera

conducted by Toscanini sounded like.

With the help of his son Walter, Toscanini spent his remaining years editing tapes and transcriptions of his performances with the NBC Symphony. The "approved" recordings were issued by RCA Victor, which also has issued his recordings with the La Scala Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Philadelphia Orchestra. His recordings with the BBC Symphony Orchestra (1937 – 39) and the Philharmonia Orchestra (1952) were issued by EMI. Various companies have issued recordings on compact discs of a number of broadcasts and concerts that he did not officially approve. Among these are stereophonic recordings of his last two NBC broadcast concerts.

Sachs and other biographers have documented the numerous conductors, singers, and musicians who visited Toscanini during his retirement. He was a big fan of early television, especially boxing and wrestling telecasts, as well as comedy programs.

Toscanini died on January 16, 1957 at the age of 89 at his home in the Riverdale section of the Bronx in New York City. His body was returned to Italy and was buried in the Cimitero Monumentale in Milan. His epitaph is taken from one account of his remarks concluding the 1926 premiere of Puccini's unfinished Turandot: "Qui finisce l'opera, perché a questo punto il maestro č morto" ("Here the opera ends, because at this point the maestro died"). During his funeral service, Leyla Gencer sang an aria from Verdi's Requiem.

In his will, he left his baton to his protégée Herva Nelli, who sang in the broadcasts of Otello, Aďda, Falstaff, the Verdi Requiem, and Un ballo in maschera.

Toscanini was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1987.

Toscanini married Carla De Martini on June 21, 1897, when she was not yet 20 years old. Their first child, Walter, was born on March 19, 1898. A daughter, Wally, was born on January 16, 1900. Carla gave birth to another boy, Giorgio, in September 1901, but he died of diphtheria on June 10, 1906. Then, that same year, Carla gave birth to their second daughter, Wanda.

Toscanini worked with many great singers and musicians throughout his career, but few impressed him as much as Vladimir Horowitz. They worked together a number of times and even recorded Brahms' second piano concerto and Tchaikovsky's first piano concerto with the NBC Symphony for RCA. Horowitz also became close to Toscanini and his family. In 1933, Wanda Toscanini married Horowitz, with the conductor's blessings and warnings. It was Wanda's daughter, Sonia, who was once photographed by Life playing with the conductor.

During World War II, Toscanini lived in Wave Hill, a historic home in Riverdale.

Despite the reported infidelities revealed in Toscanini's letters

documented by Harvey Sachs, he remained married to Carla until she died

on June 23, 1951.

At La Scala, which had what was then the most modern stage lighting system installed in 1901 and an orchestral pit installed in 1907, Toscanini pushed through reforms in the performance of opera. He insisted on dimming the house lights during performances. As his biographer Harvey Sachs wrote: "He believed that a performance could not be artistically successful unless unity of intention was first established among all the components: singers, orchestra, chorus, staging, sets and costumes."

Toscanini favored the traditional orchestral seating plan with the first violins and cellos on the left, the violas on the near right, and the second violins on the far right.

Toscanini conducted the world premieres of many operas, four of which have become part of the standard operatic repertoire: Pagliacci, La bohčme, La fanciulla del West and Turandot; he took an active role in Alfano's completion of Puccini's Turandot. He also conducted the first Italian performances of Siegfried, Götterdämmerung, Salome, Pelléas et Mélisande, and Euryanthe, as well as the South American premieres of Tristan und Isolde and Madama Butterfly and the North American premiere of Boris Godunov. He also conducted the world premiere of Samuel Barber's most famous work, the Adagio for Strings.

Toscanini made his first recordings in December 1920 with the La Scala Orchestra in the Trinity Church studio of the Victor Talking Machine Company in Camden, New Jersey, and his last with the NBC Symphony Orchestra in June 1954 in Carnegie Hall. His entire catalog of commercial recordings was issued by RCA Victor, save for two single sided recordings for Brunswick in 1926 with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and a series of excellent recordings with the BBC Symphony Orchestra from 1937 to 1939 for EMI's HMV label (which was RCA Victor's European affiliate). Besides the 1926 recordings with the New York Philharmonic (his first with the electrical process), Toscanini made a series of recordings with them for Victor, in Carnegie Hall, in 1929 and 1936. He also recorded with the Philadelphia Orchestra for RCA Victor in Philadelphia's Academy of Music in 1941 and 1942. All of the RCA Victor recordings have been digitally re-mastered and released on CD. There are also recorded concerts with various European orchestras, especially with La Scala Orchestra and the Philharmonia Orchestra. In April 2012, Sony Masterworks will release an 84 CD boxed set of Toscanini's complete RCA Victor recordings and original HMV recordings with the BBC Symphony.

In some of his recordings, Toscanini can be heard singing or humming. This is especially true in RCA's recording of La bohčme, recorded during broadcast concerts in NBC Studio 8-H in 1946. Tenor Jan Peerce later said that Toscanini's deep involvement in the performances helped him to achieve the necessary emotions, especially in the final moments of the opera when the beloved Mimi (played by Licia Albanese) is dying. During the "Tuba mirum" section of the January 1951 live recording of Verdi's Requiem, Toscanini can be heard on the disc shouting as the brass blares. In his recording of Richard Strauss' Death and Transfiguration, Toscanini sighed loudly near the end of the music; RCA Victor left this in the released recording.

He was especially famous for his performances of Beethoven, Brahms, Wagner, Richard Strauss, Debussy and his own compatriots Rossini, Verdi, Boito and Puccini. He made many recordings, especially towards the end of his career, which are still in print. In addition, there are many recordings available of his broadcast performances, as well as his remarkable rehearsals with the NBC Symphony.

Charles O'Connell, who produced many of Toscanini's RCA Victor recordings in the 1930s and early 1940s, said that RCA quickly decided to record the NBC Symphony Orchestra in Carnegie Hall, whenever possible, after being disappointed with the dull sounding early recordings in Studio 8-H in 1938 and 1939. (Nevertheless, there were a few recording sessions in Studio 8-H as late as June 1950, probably because of improvements to the acoustics in 1939, including installation of an acoustical shell.) O'Connell, and others, often complained that Toscanini was little interested in recording and, as Harvey Sachs wrote, Toscanini was frequently disappointed that the microphones failed to pick up everything he heard during the recording sessions. O'Connell even complained of Toscanini's failure to cooperate with RCA during the sessions. Toscanini himself was often disappointed that the 78 rpm discs failed to fully capture all of the instruments in the orchestra; those fortunate to attend Toscanini's concerts later said the NBC string section was especially outstanding.

O'Connell also extensively documented RCA's technical problems

with the

Philadelphia Orchestra recordings of 1941 - 42, which required extensive

electronic editing before they could be released (well after Toscanini's

death, beginning in 1963, with the rest following in the 1970s). Harvey

Sachs also recounts that the masters were damaged, possibly due to the

use of somewhat inferior materials imposed by wartime restrictions.

Unfortunately, a Musicians Union recording ban from 1942 to 1944

prevented immediate retakes; by the time the ban ended, the Philadelphia

Orchestra had left RCA Victor for Columbia Records and RCA apparently was hesitant to promote the orchestra any further.

Eventually, Toscanini recorded all of the same music with the NBC

Symphony. In 1968, the Philadelphia Orchestra returned to RCA and the

company was more favorable toward issuing all of the discs. As for the

historic recordings, even on the CD versions, first released in 1991,

some of the sides have considerable surface noise and some distortion,

especially during the louder passages. The best sounding of the

recordings is the Schubert Symphony No. 9 (The "Great"),

which had been restored by RCA first (in 1963) and released on LP. The

rest of the recordings were not issued until 1977 and, as Sachs noted,

by that time some of the masters may have deteriorated further.

Nevertheless, despite the occasional problems, the entire set is an

impressive document of Toscanini's collaboration with the Philadelphia

musicians. A 2006 RCA reissue, makes more use of digital processing in

an attempt to produce better sound. Longtime Philadelphia director

Eugene Ormandy expressed his appreciation for what Toscanini achieved

with the orchestra.

In the late 1940s when magnetic tape replaced direct wax disc recording and high fidelity long playing records were introduced, the conductor said he was much happier making recordings. Sachs wrote that an Italian journalist, Raffaele Calzini, said Toscanini told him, "My son Walter sent me the test pressing of the [Beethoven] Ninth from America; I want to hear and check how it came out, and possibly to correct it. These long playing records often make me happy."

NBC had recorded all of Toscanini's broadcast performances on transcription discs from the start of the broadcasts in 1937. The use of high fidelity sound film was common for recording sessions, as early as 1941. By 1948, when RCA began using magnetic tape on a regular basis, high fidelity became the norm for Toscanini's, and all other commercial recordings. With RCA's experiments in stereo in early 1954, stereo tapes were made of Toscanini's final two broadcast concerts, as well as the rehearsals, as documented by Samuel Antek in This Was Toscanini. The microphones were placed relatively close to the orchestra and with limited separation, so the stereo effects were not as dramatic as the commercial "Living Stereo" recordings which RCA Victor began to make about the same time with the Boston Symphony Orchestra and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The two Toscanini concerts recorded in stereo have been issued on LP and CD and have also been offered for download in digitally enhanced sound by Pristine Classical, a company which produces digitally enhanced versions of older classical recordings.

One more example of Toscanini and the NBC Symphony in stereo now also exists. It is of the January 27, 1951 concert devoted to the Verdi Requiem, previously recorded and released in high fidelity monophonic sound by RCA Victor. Recently a separate recording of the same performance, using a different microphone in a different location, was acquired by Pristine Audio. Using modern digital technology the company constructed a stereophonic version of the performance from the two recordings which it made available in 2009. The company calls this an example of "accidental stereo".

Many hundreds of hours of Toscanini's rehearsals were recorded. Some of these have circulated in limited edition recordings. Many broadcast recordings with orchestras other than the NBC have also survived, including: The New York Philharmonic from 1933 – 36, 1942, and 1945; The BBC Symphony Orchestra from 1935 – 1939; The Lucerne Festival Orchestra; and broadcasts from the Salzburg Festival in the late 1930s. Documents of Toscanini's guest appearances with the La Scala Orchestra from 1946 until 1952 include a live recording of Verdi's Requiem with the young Renata Tebaldi. Toscanini's ten NBC Symphony telecasts from 1948 until 1952 were preserved in kinescope films of the live broadcasts. These films, issued by RCA on VHS tape and laser disc and on DVD by Testament, provide unique video documentation of the passionate yet restrained podium technique for which he was well known.

A guide to Toscanini's recording career can be found in Mortimer H.

Frank's "From the Pit to the Podium: Toscanini in America" in International Classical Record Collector (1998, 15 8-21) and Christopher Dyment's "Toscanini's European Inheritance" in International Classical Record Collector

(1998, 15 22-8). Frank and Dyment also discuss Maestro Toscanini's

performance history in the 50th anniversary issue of Classic Record

Collector (2006, 47) Frank with 'Toscanini – Myth and Reality' (10–14)

and Dyment 'A Whirlwind in London' (15–21) This issue also contains

interviews with people who performed with Toscanini – Jon Tolansky

'Licia Albanese – Maestro and Me' (22-6) and 'A Mesmerising Beat: John

Tolansky talks to some of those who worked with Arturo Toscanini, to

discover some of the secrets of his hold over singers, orchestras and

audiences.' (34-7). There is also a feature article on Toscanini's

interpretation of Brahms's First Symphony – Norman C. Nelson, 'First

Among Equals [...] Toscanini's interpretation of Brahms's First Symphony

in the context of others' (28–33)

In 1969, Clyde J. Key acted on a dream he had of meeting Toscanini by starting the Arturo Toscanini Society to release a number of "unapproved" live performances by Toscanini. As Time Magazine reported, Key scoured the U.S. and Europe for off - the - air transcriptions of Toscanini broadcasts, acquiring almost 5,000 transcriptions (all transferred to tape) of previously unreleased material — a complete catalog of broadcasts by the Maestro between 1933 and 1954. It included about 50 concerts that were never broadcast, but which were recorded surreptitiously by engineers supposedly testing their equipment.

A private, nonprofit club based in Dumas, Texas, it offered members five or six LPs annually for a $25 - a - year membership fee. Key's first package offering included Brahms' German Requiem, Haydn's Symphonies Nos. 88 and 104, and Richard Strauss' Ein Heldenleben, all NBC Symphony broadcasts dating from the late 1930s or early 1940s. In 1970, the Society releases included Sibelius' Symphony No. 4, Mendelssohn's "Scottish" Symphony, dating from the same NBC period; and a Rossini - Verdi - Puccini LP emanating from the post War reopening of La Scala on May 11, 1946 with the Maestro conducting. That same year it released a Beethoven bicentennial set that included the 1935 Missa Solemnis with the Philharmonic and LPs of the 1948 televised concert of the ninth symphony taken from an FM radio transcription, complete with Ben Grauer's comments. (In the early 1990s, the kinescopes of these and the other televised concerts were released by RCA with soundtracks dubbed in from the NBC radio transcriptions; in 2006, they were re-released by Testament on DVD.)

Additional releases included a number of Beethoven symphonies recorded with the New York Philharmonic during the 1930s, a performance of Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 27 on February 20, 1936, at which Rudolf Serkin made his New York debut, and one of the most celebrated underground Toscanini recordings of all, the legendary 1940 broadcast version of Beethoven's Missa Solemnis, which has better soloists (Zinka Milanov, Jussi Bjoerling, both in their prime) and a more powerful style than the 1953 RCA studio recording, although the microphone placement was kinder to the soloists in 1953.

Because the Arturo Toscanini Society was nonprofit, Key said he believed he had successfully bypassed both copyright restrictions and the maze of contractual ties between RCA and the Maestro's family. However, RCA's attorneys were soon looking into the matter to see if they agreed. As long as it stayed small, the Society appeared to offer little real competition to RCA. But classical LP profits were low enough even in 1970, and piracy by fly - by - night firms so prevalent within the industry (an estimated $100 million in tape sales for 1969 alone), that even a benevolent buccaneer outfit like the Arturo Toscanini Society had to be looked at twice before it could be tolerated.

Magazine and newspaper reports subsequently detailed legal action

taken against Key and the Society, presumably after some of the LPs

began to appear in retail stores. Toscanini fans and record collectors

were dismayed because, although Toscanini had not approved the release

of these performances in every case, many of them were found to be

further proof of the greatness of the Maestro's musical talents. One

outstanding example of a remarkable performance not approved by the

Maestro was his December 1948 NBC broadcast of Dvořák's Symphonic Variations,

released on an LP by the Society. (A kinescope of the same performance,

from the television simulcast, has been released on VHS and laser disc

by RCA/BMG and on DVD by Testament.) There was speculation that, the

Toscanini family itself, prodded by his daughter Wanda, sought to defend

the Maestro's original decisions, made mostly during his last years, on

what should be released. Walter Toscanini later admitted that his

father probably rejected performances that were okay. Whatever the real

reasons, the Arturo Toscanini Society was forced to disband and cease

releasing any further recordings.

Arturo Toscanini was one of the first conductors to make extended appearances on live television. Between 1948 and 1952, he conducted ten concerts telecast on NBC, including a two part concert performance of Verdi's complete opera Aida starring Herva Nelli and Richard Tucker, and the first complete telecast of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony. All of these were simulcast on radio. These concerts were all shown only once during that four year span, but they were preserved on kinescopes.

The telecasts began on March 20, 1948, with an all Wagner program, including the Prelude to Act III of Lohengrin; the overture and bacchanale from Tannhäuser; "Forest Murmurs" from Siegfried; "Dawn and Siegfried's Rhine Journey" from Götterdämmerung; and "The Ride of the Valkyries" from Die Walküre. Beethoven's Ninth Symphony was telecast on April 3, 1948. On November 13, 1948, there was an all Brahms program, including the Concerto for Violin, Cello, and Orchestra in A minor (Mischa Mischakoff, violin; Frank Miller, cello); Liebeslieder - Walzer, Op. 52 (with two pianists and a small chorus); and Hungarian Dance No. 1 in G minor. On December 3, 1948, Toscanini conducted Mozart's Symphony No. 40 in G minor; Dvořák's Symphonic Variations; and Wagner's original overture to Tannhäuser.

There were two telecasts in 1949, both devoted to the performance of Verdi's Aida from studio 8H. Acts I and II were telecast on March 26 and III and IV on April 2. Portions of the audio were rerecorded in June 1954 for the commercial release on LP records. As the video shows, the soloists were placed close to Toscanini, in front of the orchestra, while the robed members of the Robert Shaw Chorale were on risers behind the orchestra.

There were no telecasts in 1950, but they resumed from Carnegie Hall on November 3, 1951, with Weber's overture to Euryanthe and Brahms' Symphony No. 1. On December 29, 1951, there was another all Wagner program that included the two excerpts from Siegfried and Die Walküre featured on the March 1948 telecast, plus the Prelude to Act II of Lohengrin; the Prelude and Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde; and "Siegfried's Death and Funeral Music" from Götterdämmerung.

On March 15, 1952, Toscanini conducted the Symphonic Interlude from Franck's Rédemption; Sibelius's En Saga; Debussy's "Nuages" and "Fetes" from Nocturnes; and the overture of Rossini's William Tell. The final telecast, on March 22, 1952, included Beethoven's Symphony No. 5, and Respighi's The Pines of Rome.

The NBC cameras were often left on Toscanini for extended periods, documenting not only his baton techniques but his deep involvement in the music. At the end of a piece, Toscanini generally nodded rather than bowed and exited the stage quickly. Although NBC continued to broadcast the orchestra on radio until April 1954, telecasts were abandoned after March 1952.

As part of a restoration project initiated by the Toscanini family in

the late 1980s, the kinescopes were fully restored and issued by RCA on

VHS and laser disc

beginning in 1989. The audio portion of the sound was taken, not from

the noisy kinescopes, but from 33 1/3 rpm 16 inch transcription disc and

high fidelity

audio tape recordings made simultaneously by RCA technicians during the

televised concerts. The hi-fi audio was synchronized with the kinescope

video for the home video release. Original introductions by NBC's

longtime announcer Ben Grauer were replaced with new commentary by

Martin Bookspan. The entire group of Toscanini videos has since been

reissued by Testament on DVD, with further improvements to the sound.

In 1943, Toscanini made a 31 minute film for the United States Office of War Information called Hymn of the Nations, directed by Alexander Hammid. It was mostly filmed in NBC's Studio 8-H and consists of Toscanini conducting the NBC Symphony in a performance of Verdi's Overture to La Forza del Destino and Verdi's "Hymn of the Nations" (Inno delle nazioni), which contains national anthems of England, France and Italy (the World War I allied nations), to which Toscanini added the Soviet "Internationale" and "The Star Spangled Banner". Tenor Jan Peerce and the Westminster Choir performed in the latter work and the film was narrated by Burgess Meredith.

The film was released by RCA/BMG on DVD in 2004. By this time the "Internationale" had been cut from the 1943 film, but the complete "Hymn of the Nations" can still be heard in the audio recording which accompanied the DVD on a CD. Hymn of the Nations was nominated for a 1944 Academy Award for Best Documentary Short.

Toscanini: The Maestro is a 1985 documentary made for cable television. The film features archival footage of the conductor and interviews with musicians who worked with him. This film was released on VHS and in 2004 on the same DVD with Hymn of the Nations.

Toscanini is the subject of the 1988 fictionalized biography Il giovane Toscanini (Young Toscanini), starring C. Thomas Howell and Dame Elizabeth Taylor, and directed by Franco Zeffirelli.

It received scathing reviews and was never officially released in the

United States. The film is a fictional recounting of the events that led

up to Toscanini making his conducting debut in Rio de Janeiro in 1886.

Although nearly all of the plot is embellished, the events surrounding

the sudden and unexpected conducting debut are based on fact.

Throughout his career, Toscanini was virtually idolized by the critics (a notable exception being Virgil Thomson), as well as by most fellow musicians and the public alike. He enjoyed the kind of consistent critical acclaim during his life that few other musicians have had. He was featured three times on the cover of Time magazine, in 1926, 1934, and again in 1948. In the magazine's history, he is the only conductor to have been so honored. On March 25, 1989, the United States Postal Service issued a 25 cent postage stamp in his honor. While online critics such as Peter Gutmann have dismissed much of what was written about Toscanini during his lifetime as "adoring puffery", it nevertheless remains a fact that composers and others who worked with the Maestro readily acknowledged what they felt was his greatness, and audio interviews containing the praise of such luminaries as Aaron Copland still exist.

Over the past thirty years or so, however, as a new generation has appeared, there has been an increasing amount of revisionist criticism directed at Toscanini. These critics contend that Toscanini was ultimately a detriment to American music rather than an asset because of the tremendous marketing of him by RCA as the greatest conductor of all time and his preference to perform mostly older European music. According to Harvey Sachs, Mortimer Frank, and B.H. Haggin, this criticism can be traced to the lack of focus on Toscanini as a conductor rather than his legacy. Frank, in his recent book Toscanini: The NBC Years, rejects this revisionism quite strongly, and cites the author Joseph Horowitz (author of Understanding Toscanini) as perhaps the most extreme of these critics. Frank writes that this revisionism has unfairly influenced younger listeners and critics, who may have not heard as many of Toscanini's performances as older listeners, and as a result, Toscanini's reputation, extraordinarily high in the years that he was active, has suffered a decline. Conversely, Joseph Horowitz contends that those who keep the Toscanini legend alive are members of a "Toscanini cult", an idea not altogether refuted by Frank, but not embraced by him, either.

Some contemporary critics, particularly Virgil Thomson, also took Toscanini to task for not paying enough attention to the "modern repertoire" (i.e., 20th century composers, of which Thomson was one). It may be speculated, knowing Toscanini's antipathy toward much 20th century music, that perhaps Thomson had a feeling that the conductor would never have played any of his (Thomson's) music, and that perhaps because of this, Thomson bore a resentment against him. During Toscanini's middle years, however, such now widely accepted composers as Claude Debussy, whose music the conductor held in very high regard, were considered to be radical and modern.

Another criticism leveled at Toscanini stems from the constricted sound quality that comes from many of his recordings, notably those made in NBC's Studio 8-H. Studio 8-H was foremost a radio and later a television studio, not a true concert hall. Its dry acoustics lacking in much reverberation, while ideal for broadcasting, were unsuited for symphonic concerts and opera. However, it is widely believed that Toscanini favored it because its close miking enabled listeners to hear every instrumental strand in the orchestra clearly, something that the conductor strongly believed in.

Toscanini has also been criticized for lack of nuance and metronomic (rhythmically too rigid) performances:

"Others attacked the conductor on the ground that he was a slave to the metronome. They said that his beat was inexorable, that his rhythms were rigid, that he was an enemy of Italian song and a wrecker of the art of bel canto."

"When he was young as a conductor, it was complained of Toscanini that he held the tempo and rhythm of the music firmly to its course and that it had the mechanical exactitude of a metronome. [...]"—The Maestro: The Life Of Arturo Toscanini (1951) by Howard Taubman

Others state (and there is some evidence from the recordings) that Toscanini's tempos, quite flowing in his earlier recordings, became stricter as he got older, although this is not to be taken as a literally true statement. His 1953 recording of Pictures at an Exhibition, for instance, and his 1950 La Mer, are considered masterpieces by many.

Beginning in 1963, NBC Radio broadcast a weekly series of programs entitled Toscanini: The Man Behind The Legend, commemorating Toscanini's years with the NBC Symphony Orchestra. The show, hosted by NBC announcer Ben Grauer, who had also hosted many of the original Toscanini broadcasts, featured interviews with members of the conductor's family, as well as musicians of the NBC Symphony, David Sarnoff, and noted classical musicians who had worked with the conductor, such as Giovanni Martinelli. It spotlighted partial or complete rebroadcasts of many of Toscanini's recordings. The program ran for at least three years, and did not feature any of the revisionist commentary about the conductor one finds so often today in magazines such as American Record Guide.

In 1986, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts purchased the bulk of Toscanini's papers, scores and sound recordings from his heirs. Named The Toscanini Legacy, this vast collection contains thousands of letters, programs and various documents, over 1,800 scores and more than 400 hours of sound recordings. A finding aids for the scores and sound recordings is available on the library's website. In house finding aids are available for other parts of the collection.

The Library also has many other collections that have Toscanini materials in them, such as the Bruno Walter papers, the Fiorello H. La Guardia papers, and a collection of material from Rose Bampton.

- Of German composer Richard Strauss, whose political behavior during World War II was arguably very questionable: "To Strauss the composer I take off my hat; to Strauss the man I put it back on again."

- "The conduct of my life has been, is, and will always be the echo and reflection of my conscience."

- "Gentlemen, be democrats in life but aristocrats in art."

- Referring to the first movement of the Eroica: "To some it is Napoleon, to some it is a philosophical struggle. To me it is allegro con brio."

- At the point where Puccini left off writing the finale of his unfinished opera, Turandot: "Here Death triumphed over art". (Toscanini then left the opera pit, the lights went up and the audience left in silence.).

- Toscanini was invited in the year 1940 to visit a movie set at the Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studios. There he said with tears in his eyes, "I will remember three things in my life: the sunset, the Grand Canyon and Eleanor Powell's dancing."

George Szell (June 7, 1897 – July 30, 1970), originally György Széll, György Endre Szél, or Georg Szell, was a Hungarian born American conductor and composer. He is remembered today for his long and successful tenure as music director of the Cleveland Orchestra, and for the recordings of the standard classical repertoire he made in Cleveland and with other orchestras.

Szell came to Cleveland in 1946 to take over a respected if

undersized orchestra, which was struggling to recover from the

disruptions of World War II.

By the time of his death he was credited, to quote the critic Donal

Henahan, with having built it into "what many critics regarded as the

world's keenest symphonic instrument."

Through his recordings, Szell has remained a presence in the classical

music world long after his death, and his name remains synonymous with

that of the Cleveland Orchestra. While on tour with the Orchestra in the

late 1980s, then Music Director Christoph von Dohnányi remarked, "We

give a great concert, and George Szell gets a great review."

Szell was born in Budapest but grew up in Vienna. He began his formal music training as a pianist, studying with Richard Robert. One of Robert's other students was Rudolf Serkin; Szell and Serkin became lifelong friends and musical collaborators. In addition to the piano, Szell studied composition with Eusebius Mandyczewski (a personal friend of Brahms), and with Max Reger for a brief period. Although his work as a composer is virtually unknown today, when he was fourteen Szell signed a ten year exclusive publishing contract with Universal Edition in Vienna. In addition to writing original pieces, he arranged Bedřich Smetana's String Quartet No. 1, From My Life, for orchestra.

At age eleven, Szell began touring Europe as a pianist and composer,

making his London debut at that age. Newspapers declared him "the next Mozart."

Throughout his teenage years he performed with orchestras in this dual

role, eventually making appearances as composer, pianist and conductor,

as he did with the Berlin Philharmonic at age seventeen.

Szell quickly realized that he was never going to make a career out of being a composer or pianist, and that he much preferred the artistic control he could achieve as a conductor. He made an unplanned public conducting debut when he was seventeen, while vacationing with his family at a summer resort. The Vienna Symphony's conductor had injured his arm, and Szell was asked to substitute. Szell quickly turned to conducting full time. Though he abandoned composing, throughout the rest of his life he occasionally played the piano with chamber ensembles and as an accompanist. Despite his rare appearances as a pianist after his teens, he remained in good form. During his Cleveland years he occasionally would demonstrate to guest pianists how he thought they should play a certain passage.

In 1915, at the age of 18, Szell won an appointment with Berlin's Royal Court Opera (now known as the Staatsoper). There, he was befriended by its Music Director, Richard Strauss. Strauss instantly recognized Szell's talent and was particularly impressed with how well the teenager conducted Strauss's music. Strauss once said that he could die a happy man knowing that there was someone who performed his music so perfectly. In fact, Szell ended up conducting part of the world premiere recording of Don Juan for Strauss. The composer had arranged for Szell to rehearse the orchestra for him, but having overslept, showed up an hour late to the recording session. Since the recording session was already paid for, and only Szell was there, Szell conducted the first half of the recording (since no more than four minutes of music could fit onto one side of a 78, the music was broken up into four sections). Strauss arrived as Szell was finishing conducting the second part; he exclaimed that what he heard was so good that it could go out under his own name. Strauss went on to record the last two parts, leaving the Szell conducted half as part of the full world premiere recording of Don Juan.

Szell credited Strauss as being a major influence on his conducting style. Much of his baton technique, the Cleveland Orchestra’s lean, transparent sound, and Szell's willingness to be an orchestra builder all came from Strauss. The two remained friends after Szell left the Royal Court Opera in 1919; even after World War II, when Szell had settled in the United States, Strauss kept track of how his protégé was doing.

In the fifteen years during and after World War I Szell worked with opera houses and orchestras in Europe: in Berlin, Strasbourg — where he succeeded Otto Klemperer at the Municipal Theatre — Prague, Darmstadt, Düsseldorf, and Glasgow, before becoming principal conductor, in 1924, of the Berlin Staatsoper, which had replaced the Royal Opera. In 1930, Szell made his United States debut with the Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra. At this time he was better known as an opera conductor than an orchestral one.

At the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, Szell was returning via the

U.S. from an Australian tour; he ended up settling with his family in

New York City.

After spending a year teaching, Szell began to receive frequent guest

conducting invitations. Important among these invitations was a series

of four concerts with Arturo Toscanini’s NBC Symphony Orchestra in 1941.

In 1942 he made his Metropolitan Opera debut; he conducted the company

regularly for the next four years. In 1943 he made his New York

Philharmonic debut. In 1946 he became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

In 1946, Szell was asked to become the Music Director of the Cleveland Orchestra. At the time the Cleveland Orchestra was a highly regarded regional American orchestra (the top tier American orchestras were Philadelphia Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic and NBC Symphony Orchestra). For Szell, working in Cleveland would represent an opportunity to create his own personal ideal orchestra, one which would combine the virtuosity of the best American ensembles, with the homogeneity of tone of the best European orchestras. Szell made it clear to the trustees of the Orchestra that if they wanted him to be their next conductor, they would have to agree to give him total artistic control of the Orchestra; they agreed. He held this post until his death.

The next decade was spent firing musicians, carefully hiring replacements, increasing the orchestra's roster to over one hundred players, and relentlessly drilling the orchestra. Szell's rehearsals were legendary for their intensity. Absolute perfection was demanded from every player. Musicians would be dismissed on the spot for making too many mistakes or simply questioning Szell's authority. Although Szell was not alone in this practice — Toscanini was nothing if not dictatorial — such firings would not happen today: musicians' unions are much stronger now than they were then. If Szell heard a player practicing backstage before a concert and did not like what he heard, he would not hesitate to berate the musician and give detailed notes on how the music should be played, despite the concert being minutes away. Szell’s autocratic style extended to giving suggestions to the Severance Hall janitorial staff on mopping technique and what brand of toilet paper to use in the restrooms.

Szell proudly boasted: "the Cleveland Orchestra gives seven concerts a week and the public is invited to two." Some critics found the Orchestra to sound over - rehearsed in concert, lacking spontaneity. Szell conceded this critique, saying that the orchestra did much of its best work during rehearsals. But Szell's high standards paid off. According to music critic Ted Libbey, "Szell's formidable musicianship and paternal authority commanded equal measures of respect from the Cleveland players, who under his baton achieved what was probably the highest executant standard of any orchestra in the world."

By the end of the 1950s it became clear to the world that the

Cleveland Orchestra, noted for its flawless precision and chamber like

sound, had taken its place alongside the greatest orchestras in America

and Europe. In addition to taking the Orchestra on annual tours to

Carnegie Hall and the East Coast, Szell led the orchestra on its first

international tours to Europe, the Soviet Union, Australia and Japan.

Szell's manner in rehearsal was that of an autocratic taskmaster. He meticulously prepared for rehearsals and could play the entire score on the piano from memory. Preoccupied with phrasing, transparency, balance and architecture, Szell also insisted upon hitherto unheard of rhythmic discipline from his players. The result was often a level of precision and ensemble playing normally found only in the best string quartets. For all Szell's absolutist methods, many of the orchestra's players were proud of the musical integrity to which he aspired. Video footage also shows that Szell took care to explain what he wanted and why, expressed delight when the orchestra produced what he was aiming for, and avoided over - rehearsing parts that were in good shape. His left hand, which he used to shape each sound, was often called the most graceful in music.

As a result of Szell's exactitude and very thorough rehearsals, some critics (such as Donald Vroon, editor of American Record Guide) have censured Szell's music making as lacking emotion. In response to such criticism, Szell expressed this credo: "The borderline is very thin between clarity and coolness, self discipline and severity. There exist different nuances of warmth — from the chaste warmth of Mozart to the sensuous warmth of Tchaikovsky, from the noble passion of Fidelio to the lascivious passion of Salome. I cannot pour chocolate sauce over asparagus." He further stated: "It is perfectly legitimate to prefer the hectic, the arhythmic, the untidy. But to my mind, great artistry is not disorderliness."

He has been described as a "literalist", playing only what is in the score. However, Szell was quite prepared to play music in unconventional ways if he thought the music needed these; and, like most other conductors before and since, he made many small modifications to orchestrations and even notes in the works of Beethoven, Schubert and others. His recordings of the four Schumann symphonies contain changes to the composer's orchestration (slight changes, admittedly, and fewer than most other prominent conductors have made).

A stickler for perfection, Szell could at times seem almost absurdly stubborn, but he always aimed only to get the best results. His great expertise regarding instrumental techniques assisted him in this respect.

Cloyd Duff, timpanist with the Cleveland

Orchestra, once recalled how Szell had insisted that he play the snare

drum part in Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra, an instrument which he was

not supposed to play. A month after having recorded the concerto in

Cleveland (October 1959), it was to be performed at Carnegie Hall, as

part of an annual two week tour of the Eastern United States along with

Prokofiev's Symphony No. 5. Szell had begun getting increasingly

irritated about the side drum part in the second movement and by the time they reached New York,

Szell's escalation was going off the scale. "Starting with the one who

had played on the recording, Szell tried out each of the staff

percussionists on the side drum part. He made them so nervous that, one

by one, they all stumbled. Finally Szell turned to timpanist Cloyd

Duff."

- This is the story as Duff tells it:

| “ | Szell came to me and said to me, "Cloyd I want you to play the snare drum part. I remember how you played these things in Philadelphia [over twenty years earlier at the Robin Hood Dell when Szell was guest conductor and Duff was a student at Curtis]." He had an awfully good memory, he liked my percussion playing. He said, "I want you to play the part," and I really blew my lid. I said, "You're ruining the whole section. Nobody can make a diminuendo to please you because they're so nervous. Every one of those men is capable of doing that." He said, "Even so, I want you to play the part." I said, "Do you realize how silly that will look, to see me get up from the timpani to go over to the snare drum and then back to the timpani and back to the snare drum at the end?" I said, "It's really uncalled for," or words to that effect. But, he said, "OK, but I want you to play that part. It's very important that we do it just right." I said, "OK, I'll play it for you, but don't you dare look at me." So when I played it, I played it louder than they had played it before so I had more room to make a diminuendo. Everybody was a little bit shocked that I had played it as loudly as I did. But Szell, true to his word, looked away, didn't look at me once and I didn't look at him under the circumstances. | ” |

Szell's reputation as a perfectionist was well known, but his knowledge of instruments was deep and in - depth. The Cleveland trumpeter Bernard Adelstein recounted Szell's knowledge of the trumpet:

| “ | He knew all the fingerings on the trumpet. For example, on the C-trumpet, the "E" on the fourth space is played open, with no valve, and it's a flat note. But there are two other options on the C-trumpet. You can play the same note with the first and second valves or the third valve. Both of them sound sharp. The third valve is a little sharp and the first and second valves together sounds even sharper. And he knew that. He called me in once when we were playing an octave in Don Juan. He said. "The 'E' is a flat note on the C-trumpet." I said, "Yes, that's why I play it on one and two." He said, "But one and two is sharp, isn't it?" I said, "Yes, but I make an adjustment, by lengthening the first slide a little bit." And he said, "Ah, yes, but it's still out of tune." | ” |

Szell primarily conducted works from the core Austro - German classical and romantic repertoire, from Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, through Mendelssohn, Schumann and Brahms, and on to Bruckner, Mahler and Strauss. He said once that as he got older he consciously narrowed his repertoire, feeling it was "actually my task to do those works which I thought I'm best qualified to do, and for which a certain tradition is disappearing with the disappearance of the great conductors who were my contemporaries and my idols and my unpaid teachers." He did however program contemporary music; he gave numerous world premieres in Cleveland, and he was particularly associated with such composers as Dutilleux, Walton, Prokofiev, Hindemith and Bartók. Szell also helped initiate the Cleveland Orchestra's long association with composer - conductor and avant garde icon Pierre Boulez. At the same time, Szell championed the music of Haydn and Mozart in a period when those composers were little represented in concert programs.

After World War II Szell became closely associated with the Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam, where he was a frequent guest conductor and made a number of recordings. He also regularly appeared with the London Symphony Orchestra, the Vienna Philharmonic, and at the Salzburg Festival. From 1942 to 1955, he was an annual guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic and served as Musical Advisor and senior guest conductor of that orchestra in the last year of his life.

Szell married twice. The first, in 1920 to Olga Band, ended in divorce in 1926. His second marriage, in 1938 to Helene Schultz Teltsch, originally from Prague, was much happier, and lasted until his death. When not making music, he was a gourmet cook and an automobile enthusiast. He regularly refused the services of the orchestra's chauffeur and drove his own Cadillac to rehearsal until almost the end of his life. He died from bone marrow cancer in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1970. His body was cremated, and his ashes were buried, in Atlanta, along with his wife upon her death in 1990.

Most of Szell's recordings were made with the Cleveland Orchestra for Epic / Columbia Masterworks (now Sony Classical). He also made recordings with the New York Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. Few of his mono recordings have been reissued. Many live stereo recordings of repertoire Szell never conducted in the studio exist, both with the Cleveland Orchestra and other orchestras.