<Back to Index>

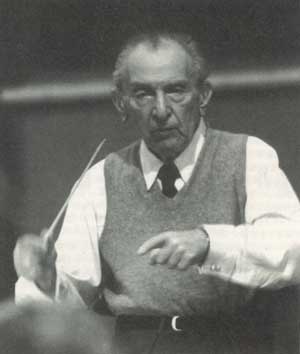

- Conductor Frederick Martin "Fritz" Reiner, 1888

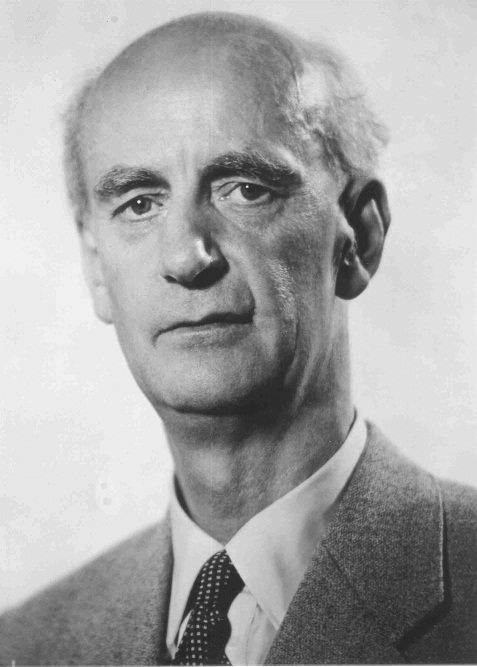

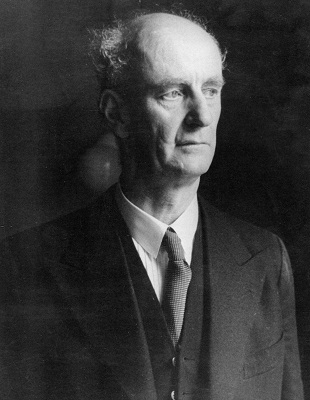

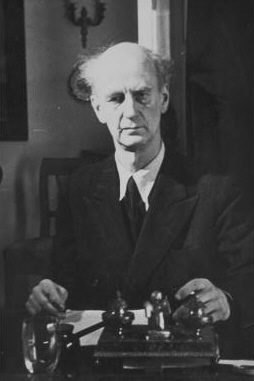

- Conductor and Composer Wilhelm Furtwängler, 1886

PAGE SPONSOR

Frederick Martin “Fritz” Reiner (December 19, 1888 – November 15, 1963) was a prominent conductor of opera and symphonic music in the twentieth century. Hungarian born and trained, he emigrated to the United States, in 1922, where he rose to prominence as a conductor with several orchestras. He reached the pinnacle of his career, while music director with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in the 1950s and early 1960s.

Reiner was born in Budapest, Hungary, to a secular Jewish family that resided in the Pest area of the city. After preliminary studies in law at his father’s urging, Reiner pursued the study of piano, piano pedagogy, and composition at the Franz Liszt Academy. During his last two years there his piano teacher was the young Béla Bartók. After early engagements at opera houses in Budapest and Dresden where he worked closely with Richard Strauss, he moved to the United States of America in 1922 to take the post of Principal Conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. He remained until 1931, having become a naturalized citizen in 1928, then began to teach at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where his pupils included Leonard Bernstein and Lukas Foss. He conducted the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra from 1938 to 1948 and made a few recordings with them for Columbia Records, then spent several years at the Metropolitan Opera, where he conducted a historic production of Strauss's Salome in 1949, with the Bulgarian soprano Ljuba Welitsch in the title role, and the American premiere of Igor Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress in 1951. He also conducted and made a recording of the famous 1952 Metropolitan Opera production of Bizet's Carmen, starring Rise Stevens. The production was telecast on closed circuit television that year. At the time of his death he was preparing the Met's new production of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung.

In 1947, Reiner appeared on camera in the film Carnegie Hall, in which he conducted the New York Philharmonic Orchestra as they accompanied violinist Jascha Heifetz in an abbreviated version of the first movement of Tchaikovsky's violin concerto. Ten years later, Heifetz and Reiner recorded the full Tchaikovsky concerto in stereo for RCA Victor in Chicago.

Reiner's music making had been largely American - focused since his arrival in Cincinnati, but after the Second World War he began markedly increasing his European activity. When he became music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in 1953 he had a completely international reputation. By common consent, the ten years that he spent in Chicago mark the pinnacle of his career, and are best remembered today through the many recordings he made in Chicago's Orchestra Hall for RCA Victor from 1954 to 1963. The first of these — of Ein Heldenleben by Richard Strauss — occurred on March 6, 1954 and was among RCA's first to use stereophonic sound. His last concerts in Chicago took place in the spring of 1963.

One of his last recordings, released in a special Reader's Digest boxed set, was a performance of Brahms' Fourth Symphony, recorded with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in October 1962 in London's Kingsway Hall. This recording was later reissued on LP by Quintessence and on CD by Chesky. On September 13 and 16, 1963, Reiner conducted a group of New York musicians in Haydn's Symphony No. 101 in D minor; this was followed by September 18 and 20, 1963, sessions devoted to Haydn's Symphony No. 95 in C minor.

He also appeared with members of the Chicago Symphony in a series of telecasts on Chicago's WGN-TV in 1953 - 54, and a later series of nationally syndicated programs called Music from Chicago. Some of these performances have been issued on DVD. The videos clearly show his stern, disciplined demeanor, but at the conclusion of a piece, Reiner would turn to the audience and smile at them as he bowed.

Reiner was married three times (one of them to a daughter of Etelka Gerster) and had three daughters. His health deteriorated after a heart attack in October 1960. He died in New York City on November 15, 1963, at the age of 74.

Reiner was especially noted as an interpreter of Strauss and Bartók and was often seen as a modernist in his musical taste; he and his compatriot Joseph Szigeti convinced Serge Koussevitzky to commission the Concerto for Orchestra from Bartók. In reality, he had a very wide repertory and was known to admire Mozart's music above all else.

Reiner’s conducting technique was defined by its precision and economy, in the manner of Arthur Nikisch and Arturo Toscanini. It typically employed quite small gestures - it has been said that the

beat indicated by the tip of his baton could be contained in the area of

a postage stamp - although from the perspective of the players it was

extremely expressive. The response he drew from orchestras was one of

astonishing richness, brilliance, and clarity of texture. Igor Stravinsky

called the Chicago Symphony under Reiner "the most precise and flexible

orchestra in the world"; it was more often than not achieved with

tactics that bordered on the personally abusive. Chicago musicians have spoken of Reiner's autocratic methods; trumpeter Adolph Herseth told National Public Radio that Reiner often tested him and other musicians.

Wilhelm Furtwängler (January 25, 1886 – November 30, 1954) was a German conductor and composer. He is widely considered to have been one of the greatest symphonic and operatic conductors of the 20th century. By the 1930s he had built a reputation as one of the leading conductors in Europe, and he was the leading conductor who remained in Germany during the Second World War. Although he was never a member of the Nazi party, the morality of his decision to remain working in Germany during this period has been continually debated since his death. However even today, many musicians, critics and record collectors still revere him for his very subjective conducting style, which is often compared and contrasted to the more objective style of Arturo Toscanini, who was probably the most famous conductor at the time. Like Toscanini, Furtwängler was a major influence on many later conductors, and his name is often mentioned when discussing their interpretive style.

Furtwängler was born in Berlin into a prominent family. His father Adolf was an archaeologist, his mother a painter. Most of his childhood was spent in Munich, where his father taught at the city's Ludwig Maximilian University. He was given a musical education from an early age, and developed an early love of Ludwig van Beethoven, a composer with whom he remained closely associated throughout his life. Though his chief posthumous fame rests on his work as a conductor, he was also a composer and regarded himself first and foremost as such, having in fact first taken up the baton in order to perform his own works.

By the time of Furtwängler's conducting debut at the age of twenty, he had written several pieces of music. However, they were not well received, and that - combined with the financial insecurity of a career as a composer - led him to concentrate on conducting. At his first concert, he led the Kaim Orchestra (now the Munich Philharmonic) in Anton Bruckner's Ninth Symphony. He subsequently held posts at Munich, Strasbourg, Lübeck, Mannheim, Frankfurt and Vienna, before securing a job at the Berlin Staatskapelle in 1920, and in 1922 at the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra where he succeeded Arthur Nikisch, and concurrently at the prestigious Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra.

Furtwängler also made a number of appearances as a conductor abroad. He made his London debut in 1924, and continued to appear there as late as 1938 to conduct a cycle of Richard Wagner's Ring. In 1925 he appeared as guest conductor of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, and made return visits in the following two years.

Towards the end of the Second World War, under extreme pressure from the Nazi Party, Furtwängler fled to Switzerland. It was during this troubled period that he composed what is largely considered his most significant work, the Symphony No. 2 in E minor. Work on the symphony was begun in 1944, and carried on into 1945. It was given its premiere in 1948 by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under Furtwängler's direction. Furtwängler and the Philharmonic recorded the symphony for Deutsche Grammophon; the music was much in the tradition of Bruckner and Gustav Mahler, composed on a grand scale for very large orchestra with romantic, dramatic themes. Another important work is the Symphonic Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, completed and premiered in 1937 and revised in 1954. Many themes from this work were also incorporated into Furtwängler's unfinished Symphony No. 3 in C sharp minor.

He resumed performing and recording following the war, and remained a popular conductor in Europe, although always under something of a shadow. He died in 1954 in Ebersteinburg, close to Baden - Baden. He is buried in the Heidelberg Bergfriedhof. The tenth anniversary of his death was marked by a concert in the Royal Albert Hall, London, conducted by his biographer Hans - Hubert Schönzeler.

Furtwängler is most famous for his performances of Beethoven, Brahms,

Bruckner and Wagner. However, he was also a champion of modern music,

notably the works of Paul Hindemith and Arnold Schoenberg, and conducted the world premiere of Sergei Prokofiev's Fifth Piano Concerto (with the composer at the piano) on October 31, 1932 as well as performances of Béla Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra.

Furtwängler's relationship with — and attitude towards — Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party was a matter of much controversy. Because of his international renown, he was appointed as the first vice - president of the Reichsmusikkammer. In 1934 he was banned from conducting the premiere of Hindemith's opera Mathis der Maler, and subsequently resigned from the RMK and the Berlin Opera. Some sources maintain that Furtwängler resigned from his posts at the Berlin Opera and Reichsmusikkammer in protest; Frederic Spotts states that he was forced to either resign all his positions or be dismissed. In 1936 it seemed possible that he might follow Erich Kleiber's footsteps into exile when he was offered the principal conductor's post at the New York Philharmonic Orchestra, where he would have succeeded Arturo Toscanini. Toscanini's biographer Harvey Sachs wrote that Toscanini recommended Furtwängler for the position, one of the few times Toscanini expressed admiration for a fellow conductor. There is every possibility that Furtwängler would have accepted the post, but a report from the Berlin branch of the Associated Press, possibly ordered by Hermann Göring, said that he was willing to take up his post at the Berlin Opera once more. This caused the mood in New York to turn against him; from their point of view, it seemed that Furtwängler was now a full supporter of the Nazi Party.

However, Furtwängler never joined the Nazi Party nor did he really approve of them, much like the composer Richard Strauss, who made no secret of his dislike of the Nazis. Furtwängler always refused to give the Nazi salute.

Furtwängler was treated relatively well by the Nazis; he had a high profile, and was an important cultural figure, as evidenced by his inclusion in the Gottbegnadeten list ("God - gifted List") of September 1944. Furtwängler in turn conducted several concerts for the direct benefit of the Nazis: in February 1938 he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic at a concert held for the Hitler Youth, and that same year conducted a performance of Wagner's Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg in celebration of Hitler's birthday. Further, contrary to the claims of some writers that he refused to conduct in occupied countries during the war, he conducted in Prague in May and November 1940, and again in March 1944 in a concert marking the fifth anniversary of the German occupation. His concerts were often broadcast to German troops to raise morale, though he was limited in what he was allowed to perform by the authorities. He later said he tried to protect German culture from the Nazis; it is now known that he used his influence to help Jewish musicians and non musicians escape the Third Reich. He managed, for example, to have Max Zweig, a nephew of conductor Fritz Zweig, released from Dachau concentration camp. Others, from an extensive list of Jews he helped, included Carl Flesch, Josef Krips and the composer Arnold Schönberg. In spite of this, some sources claim his motives were not as pure as those of, e.g., Oskar Schindler.

Albert Speer claimed that in December 1944 Furtwängler asked whether Germany had any chance of winning the war. Speer replied in the negative, and advised the conductor to flee to Switzerland from possible Nazi retribution. Furtwängler did in fact escape to Switzerland shortly after a concert in Vienna with the Vienna Philharmonic on January 28, 1945. At that concert he conducted an account of Brahms's Second Symphony that was caught on tape and is considered one of his greatest recordings.

At his denazification trial, Furtwängler was charged with supporting Nazism by remaining in Germany, performing at Nazi party functions and with making an anti - semitic remark against the part - Jewish conductor Victor de Sabata. However, he was eventually cleared on all these counts.

As part of his closing remarks at his denazification trial, Furtwängler said,

- "I knew Germany was in a terrible crisis; I felt responsible for German music, and it was my task to survive this crisis, as much as I could. The concern that my art was misused for propaganda had to yield to the greater concern that German music be preserved, that music be given to the German people by its own musicians. These people, the compatriots of Bach and Beethoven, of Mozart and Schubert, still had to go on living under the control of a regime obsessed with total war. No one who did not live here himself in those days can possibly judge what it was like.

- "Does Thomas Mann [who was critical of Furtwängler's actions] really believe that in 'the Germany of Himmler' one should not be permitted to play Beethoven? Could he not realize that people never needed more, never yearned more to hear Beethoven and his message of freedom and human love, than precisely these Germans, who had to live under Himmler’s terror? I do not regret having stayed with them."

(quoted from John Ardoin's The Furtwängler Record)

The violinist Yehudi Menuhin was among the few musicians in the Jewish community and the United States who had a positive view of Furtwängler. In 1933 he had refused to play with him, but in the late 1940s after a personal investigation of Furtwängler, he became supportive of him, and performed and recorded alongside him.

In 1949 Furtwängler accepted the position of principal conductor of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. However the orchestra was forced to rescind the offer under the threat of a boycott from several prominent musicians including Vladimir Horowitz, Arthur Rubinstein, Isaac Stern and Alexander Brailowsky. According to a New York Times report, Horowitz said that he "was prepared to forgive the small fry who had no alternative but to remain and work in Germany." But Furtwängler "was out of the country on several occasions and could have elected to keep out". Rubinstein likewise wrote in a telegram, "Had Furtwängler been firm in his democratic convictions he would have left Germany".

British playwright Ronald Harwood's play Taking Sides (1995), set in 1946 in the American zone of occupied Berlin,

is about U.S. accusations against Furtwängler of having served the Nazi

regime. In 2001 the play was made into a motion picture directed by István Szabó and starring Harvey Keitel and featuring Stellan Skarsgård in the role of Furtwängler.

Furtwängler had a unique conducting technique. He saw symphonic music as creations of nature that could only be realized subjectively into sound. This is why composers such as Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner were so central to Furtwängler's repertoire, because he identified them as great forces of nature. He disliked Toscanini's approach to the German repertoire. He walked out of a Toscanini concert once, calling him "a mere time - beater!".

Neville Cardus wrote in the Manchester Guardian in 1954 of Furtwängler's conducting style:

"He did not regard the printed notes of the score as a final statement, but rather as so many symbols of an imaginative conception, ever changing and always to be felt and realized subjectively... Not since Nikisch, of whom he was a disciple, has a greater personal interpreter of orchestral and opera music than Furtwängler been heard."

Many commentators and critics regard him as the greatest conductor in history. However, on the website Classics Today, critic David Hurwitz, a spokesman for modern literalism and precision, sharply criticizes what he terms "the Furtwangler wackos" who "will forgive him virtually any lapse, no matter how severe", and characterizes the conductor himself as "occasionally incandescent but criminally sloppy".

Conductor and pianist Christoph Eschenbach has said of Furtwängler that he was a "formidable magician, a man capable of setting an entire ensemble of musicians on fire, sending them into a state of ecstasy".

Furtwängler was famous for his exceptional inarticulacy. His pupil Sergiu Celibidache remembered that the best he could say was, "Well, just listen" (to the music). Carl Brinitzer from the German BBC service tried to interview him, and thought he had an imbecile before him. A live recording of a rehearsal with a Stockholm orchestra documents hardly anything intelligible, only hums and mumbling. On the other hand, a collection of his essays, On Music, reveals deep thought. Still, Furtwängler remained highly respected amongst musicians. Even Arturo Toscanini,

usually regarded as Furtwängler's complete antithesis (and sharply

critical of Furtwängler on political grounds), once said – when asked to

name the world's greatest conductor apart from himself – "Furtwängler!"

One of Furtwängler's protegés was pianist Karlrobert Kreiten. He was also an important influence on the pianist / conductor Daniel Barenboim, of whom Furtwängler's widow, Elisabeth Furtwängler, said, "Er furtwänglert" ("He furtwänglers"). Barenboim has conducted a recording of Furtwängler's 2nd Symphony, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Other conductors known to speak of Furtwängler in reverent tones include Valery Gergiev, Claudio Abbado, Sergiu Celibidache, Christoph Eschenbach, Alexander Frey, Eugen Jochum, Zubin Mehta, Kurt Masur and Christian Thielemann. George Szell, whose precise and martinet like musicianship was in many ways antithetical to Furtwängler's, always kept a picture of his older colleague in his dressing room. Herbert von Karajan, who in his early years was Furtwängler's most detested rival, maintained throughout his life that Furtwängler was one of the great influences on his music making, even though his cool, objective modern style had little in common with Furtwängler's white hot Romanticism. The conductor who probably most clearly represented a continuity with Furtwängler's incandescent style was Jascha Horenstein, who had worked as an assistant to Furtwängler in Berlin during the 1920s.

Furtwängler's performances of Beethoven, Wagner, Bruckner and Brahms remain important reference points today, as do his interpretations of other works such as Haydn's 88th Symphony, Schubert's Ninth Symphony and Schumann's Fourth Symphony. His performances are grounded in the spontaneous flexibility that Wagner referred to as the "elastic phrase."

There are a huge number of Furtwängler recordings currently

available, mostly live. Many of these were made during World War II

using experimental tape technology. After the war they were confiscated

by the Soviet Union

for decades, and have only recently become widely available, often on

multiple legitimate and illegitimate labels. In spite of their

limitations, the recordings from this era are widely admired by

Furtwängler devotees.