<Back to Index>

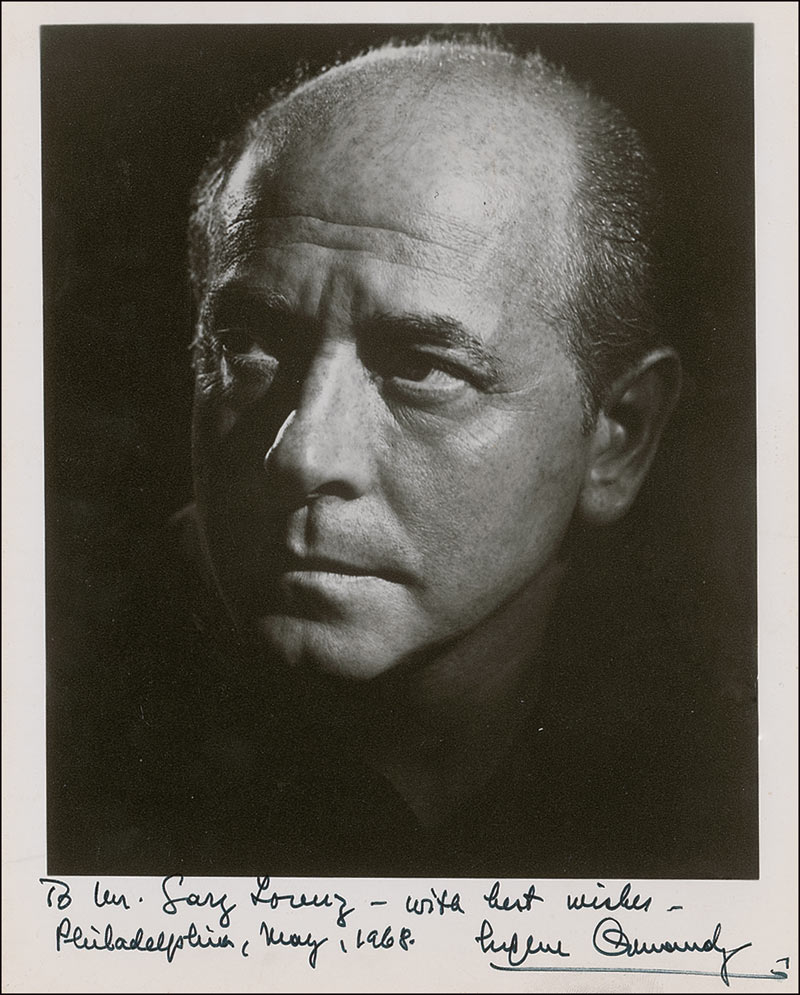

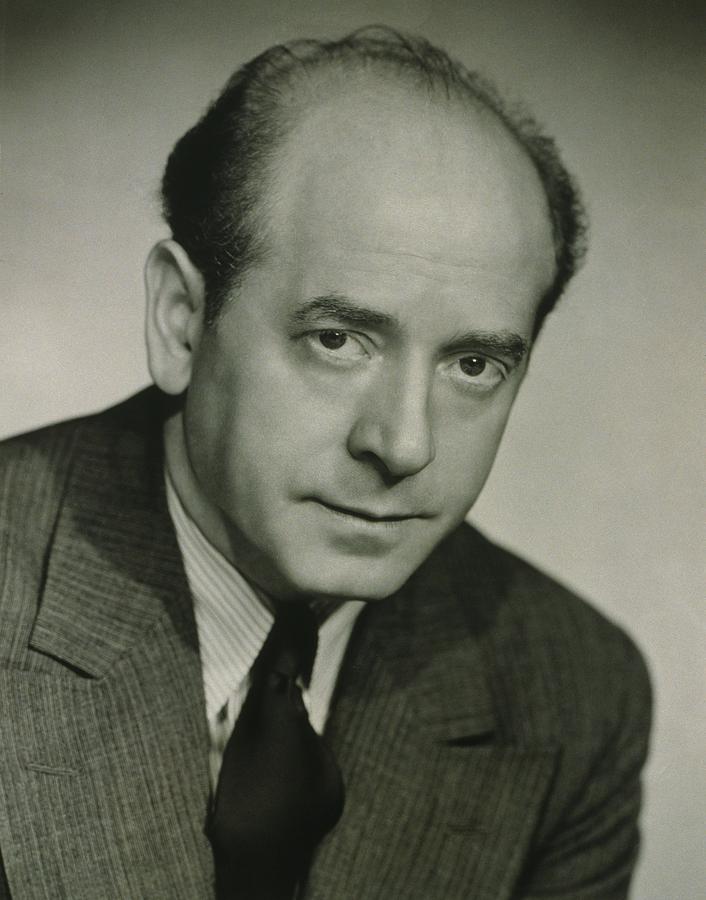

- Conductor and Violinist Eugene Ormandy, 1899

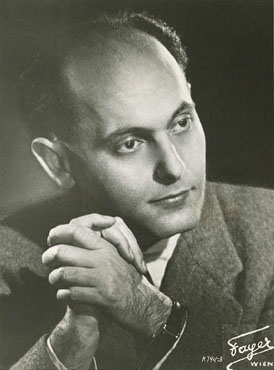

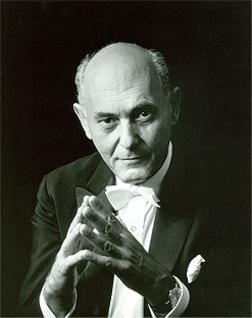

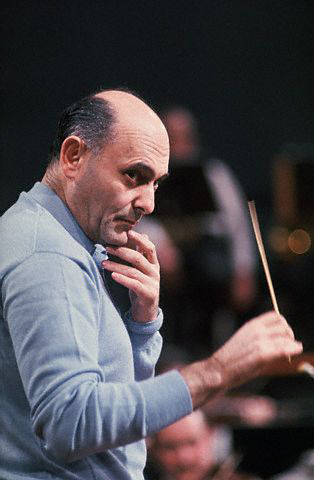

- Conductor Georg Solti, 1912

PAGE SPONSOR

Eugene Ormandy (November 18, 1899 – March 12, 1985) was a Hungarian born conductor and violinist.

Born Jenő Blau in Budapest, Hungary, Ormandy began studying violin at the Royal National Hungarian Academy of Music (now the Franz Liszt Academy of Music) at the age of five. He gave his first concerts as a violinist at age seven and, studying with Jenő Hubay, graduated at 14 with a master's degree. In 1920, he obtained a university degree in philosophy. In 1921, he moved to the United States of America. Around this time Blau changed his name to "Eugene Ormandy," "Eugene" being the equivalent of the Hungarian "Jenő." Accounts differ on the origin of "Ormandy"; it may have either been Blau's own middle name at birth, or his mother's. He was first engaged by conductor Erno Rapee, a former Budapest friend and fellow Academy graduate, as a violinist in the orchestra of the Capitol Theatre in New York City, a 77 player ensemble which accompanied silent movies. He became the concertmaster within five days of joining and soon became one of the conductors of this group. Ormandy also made 16 recordings as a violinist between 1923 and 1929, half of them using the acoustic process.

Arthur Judson, the most powerful manager of American classical music during the 1930s, greatly assisted Ormandy's career. When Arturo Toscanini was too ill to conduct the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1931, Judson asked Ormandy to stand in. This led to Ormandy's first major appointment as a conductor, in Minneapolis.

Ormandy served until 1936 as conductor of the Minneapolis Symphony

Orchestra, now the Minnesota Orchestra. During the depths of the Great

Depression, RCA Victor

contracted Ormandy and the Minneapolis Symphony for many recordings. A

clause in the musicians' contract required them to earn their salaries

by performing a certain number of hours each week (whether it be

rehearsals, concerts, broadcasts or recording). Since Victor did not

need to pay the musicians, it could afford to send its best technicians

and equipment to record in Minneapolis. Recordings were made between

January 16, 1934, and January 16, 1935. There were several premiere

recordings made in Minneapolis: John Alden Carpenter's Adventures in a Perambulator; Zoltán Kodály's Háry János Suite; Arnold Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht and a specially commissioned recording of Roy Harris's American Overture

based on "When Johnny Comes Marching Home". Ormandy's recordings also

included readings of Anton Bruckner's Symphony No. 7 and Mahler's

Symphony No. 2, which became extremely well known.

Ormandy's 44 year tenure with the Philadelphia Orchestra began in 1936 and became the source of much of his lasting reputation and fame. Two years after his appointment as associate conductor under Leopold Stokowski, he became its music director. (Stokowski continued to conduct some concerts in Philadelphia until 1941; he returned as a guest conductor in 1960.) As music director, Ormandy conducted from 100 to 180 concerts each year in Philadelphia. Upon his retirement in 1980, he was made conductor laureate.

Ormandy was a quick learner of scores, often conducting from memory and without a baton. He demonstrated exceptional musical and personal integrity, exceptional leadership skills, and a formal and reserved podium manner in the style of his idol and friend, Arturo Toscanini. One orchestra musician complimented him by saying: "He doesn't try to conduct every note as some conductors do." Under Ormandy's direction the Philadelphia Orchestra continued the lush, legato style originated by Stokowski and for which the orchestra was well known. Ormandy's conducting style was praised for its opulent sound, but also was criticized for supposedly lacking any real individual touch.

Ormandy was particularly noted for conducting late Romantic and early 20th century music. He particularly favored Bruckner, Debussy, Dvořák, Ravel, Richard Strauss, Tchaikovsky, Sibelius and transcriptions of Bach. His performances of Beethoven, Brahms, Haydn, and Mozart were considered less successful by some critics, especially when he applied the lush, so - called "Philadelphia Sound" to them. On the other hand, Donald Peck, principal flute of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, reports that a fellow flutist was won over when Ormandy conducted the Chicago in Beethoven's Ninth Symphony; he told Peck that it was the greatest Ninth he had ever heard. He was particularly noted as a champion of Sergei Rachmaninoff's music, conducting the premiere of his Symphonic Dances and leading the orchestra in the composer's own recordings of three of his piano concertos in 1939 - 40. He also directed the American premiere of several symphonies by Dmitri Shostakovich. He made the first recording of Deryck Cooke's first performing edition of the complete Mahler Tenth Symphony, which many critics praised. His recording of Camille Saint - Saëns' Third Symphony received stellar reviews and is held in high regard. He also performed a great deal of American music and gave many premičres of works by Samuel Barber, Paul Creston, David Diamond, Howard Hanson, Walter Piston, Ned Rorem, William Schuman, Roger Sessions, Virgil Thompson and Richard Yardumian.

The conductor Kenneth Woods ranked Ormandy 14th of the "Real Top 20 of Conducting," saying, "Critics hate Ormandy. It must be the first “fact” they teach at critic school - always work in an Ormandy slam into every article your write. Record collectors hate him, too. I just don’t get it. The film of him looks pretty impressive - classical and classy conducting technique, not at all showy. His Philadelphia Orchestra was the only real rival to Karajan’s Berlin for sonic beauty in the 50s - 70s, but was also a tighter and more versatile band."

In 1947, Ormandy appeared in the feature film Night Song in which he conducted Leith Stevens' Piano Concerto, with Arthur Rubinstein as soloist.

The Philadelphia Orchestra under Ormandy's direction frequently performed outside of Philadelphia, in New York and other American cities, and undertook a number of foreign tours. During a 1955 tour of Finland, Ormandy and many of the Orchestra's members visited the elderly composer Jean Sibelius at his country estate; Ormandy was photographed with Sibelius and the picture later appeared on the cover of his 1962 stereo recording of the composer's first symphony. During a 1973 tour of the People's Republic of China, the Orchestra performed to enthusiastic audiences that had been isolated from Western classical music for many decades.

Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, as well as smaller ensembles composed of its members, often collaborated with Richard P. Condie (and later Jerold Ottley) and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir to produce many recordings still considered definitive today, most notably the Grammy winning recording of the Peter Wilhousky arrangement of the Battle Hymn of the Republic.

After Ormandy officially retired as music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1980, he served as a guest conductor of other orchestras and made a few recordings.

Ormandy died in Philadelphia on March 12, 1985. His papers, including his marked scores and complete arrangements, fill 501 boxes in the archives of the University of Pennsylvania Library.

He also appeared as a guest conductor with many other orchestras. In

November 1966, he recorded a highly memorable and idiomatic rendition of

Antonín Dvořák's New World Symphony with the London Symphony

Orchestra. This and a recording in July 1952, which he conducted

anonymously with the Prades Festival Orchestra with Pablo Casals in the

Robert Schumann Cello Concerto, represented his only commercial

recordings made outside the U.S. In December 1950 he directed New York's

Metropolitan Opera in a fondly remembered production of Johann Strauss'

Die Fledermaus in English, which also was recorded. In 1978, he

conducted the New York Philharmonic in a performance of Sergei

Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 3, with Vladimir Horowitz as soloist

for a live recording.

- In honor of Ormandy's vast influence on American music and the Philadelphia performing arts community, on December 15, 1972 he was awarded the prestigious University of Pennsylvania Glee Club Award of Merit. Beginning in 1964, this award "established to bring a declaration of appreciation to an individual each year that has made a significant contribution to the world of music and helped to create a climate in which our talents may find valid expression."

- The Presidential Medal of Freedom by Richard M. Nixon in 1970

- The Ditson Conductor's Award for championing American music in 1977

- Appointed by Queen Elizabeth II an honorary Knight of the British Empire in 1976

- Awarded the Kennedy Center Honors in 1982

- He was a recipient of Yale University's Sanford Medal.

Eugene Ormandy's many recordings spanned the acoustic to the electrical to the digital age. From 1936 until his death, Ormandy made hundreds of recordings with the Philadelphia Orchestra, spanning almost every classical music genre. Writing in Audoin (1999), Richard Freed wrote: "Ormandy came about as close as any conductor anywhere to recording the "Complete Works of Everybody," with more than a few works recorded three and four times to keep up with advances in technology and / or to accommodate a new soloist or to commemorate a move to a new label."

Thomas Frost, the producer of many of Ormandy's Columbia recordings, called Ormandy "...the easiest conductor I've ever worked with — he has less of an ego problem than any of them... Everything was controlled, professional, organized. We recorded more music per hour than any other orchestra ever has." In one day, March 11, 1962, Ormandy and the Philadelphia recorded Sibelius's Symphony No. 1; the Semyon Bogatyryov arrangement of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 7 (for which Ormandy had given the Western hemisphere premiere performance); and Delius's On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring.

Curiously, the orchestra's performing venue at the Academy of Music (Philadelphia) was seldom employed for recording, because record producers believed that its dry acoustics were less than ideal. Moreover, Ormandy felt that the remodeling of the Academy of Music in the mid 1950s had ruined its acoustics. The Philadelphia Orchestra instead recorded in the ballroom of Philadelphia's Broadwood Hotel / Philadelphia Hotel, the Philadelphia Athletic Club at Broad and Race Streets, and in Town Hall / Scottish Rite Cathedral on North Broad Street near the Franklin Parkway. The latter venue featured a 1692 seat auditorium with bright resonant acoustics that made for impressive sounding "high fidelity" recordings. A fourth venue was the Old Met (Metropolitan Opera House) used for later RCA recording sessions.

Recordings were produced for the following record labels: RCA Victor Red Seal (1936 to 1942), Columbia Masterworks Records (1944 to 1968), RCA Victor Red Seal (1968 to 1980) and EMI / Angel Records (1977 - on). Three very late albums were also recorded for Telarc (1980) and Delos (1981) His first digital recording was an April 16, 1979 performance of Bela Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra for RCA.

He recorded for RCA in Minneapolis (in 1934 and 1935), too, and continued with the label until 1942, when an American Federation of Musicians ban on recordings caused the Philadelphia Orchestra to switch to Columbia, which had reached an agreement with the union in 1944, before RCA did so. Among his first recordings for Columbia was a spirited performance of Borodin's Polovtsian Dances. Ormandy conducted his first stereophonic recordings in 1957; these were not the orchestra's first stereo recordings because Leopold Stokowski had conducted experimental sessions in the early 1930s and multi - track recordings for the soundtrack of Walt Disney's 1940 feature film Fantasia. In 1968, Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra returned to RCA; among their first projects was a new performance of Tchaikovsky's Sixth symphony, the Pathetique.

His recordings of Camille Saint - Saëns' Symphony No. 3 'Organ' are considered among the best ever produced. Fanfare Magazine made this remark of the recording with renowned organist Virgil Fox: "This beautifully played performance outclasses all versions of this symphony." The Telarc recording of the symphony with Michael Murray (organist) is also highly praised.

Ormandy was also famous for being an unfailingly sensitive concerto

collaborator. His recorded legacy includes numerous first - rate

collaborations with Arthur Rubinstein, Claudio Arrau, Vladimir

Ashkenazy, Vladimir Horowitz, Rudolf Serkin, David Oistrakh, Isaac

Stern, Leonard Rose, Itzhak Perlman, Emil Gilels, Van Cliburn, Emanuel

Feuermann, Robert Casadesus, Yo-Yo Ma, Sergei Rachmaninoff and others.

World premiere recordings made by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Ormandy's baton included:

- Gustav Mahler, Symphony No. 10. Columbia, November 1965. First commercial recording of all five movements, using Deryck Cooke's performing version;

- Sergei Prokofiev, Alexander Nevsky, Jennie Tourel (mezzo - soprano), Westminster Choir. RCA Victor, May 1945;

- Prokofiev, Symphony No. 6. Columbia, January 1950;

- Prokofiev, Symphony No. 7. Columbia, April 1953;

- Dmitri Shostakovich, Cello Concerto No. 1, Mstislav Rostropovich (cello). Columbia, November 1959.

Ormandy also conducted the premiere American recordings of Paul Hindemith's Mathis der Maler symphony, Carl Orff's Catulli Carmina (which won the Grammy Award for Best Classical Choral Performance in 1968), Shostakovich's Symphonies 4, 13, 14, and 15, Carl Nielsen's Symphonies 1 & 6, Anton Webern's Im Sommerwind, Krzysztof Penderecki's Utrenja, and Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 10.

Ormandy also commissioned a version of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition

which he and the Philadelphia Orchestra could call their own, since the

Ravel arrangement was at that time still very much the property of Serge Koussevitzky,

who had commissioned it, made its first recording with the Boston

Symphony, and published the score. So Ormandy asked Lucien Cailliet

(1891 – 1984), the Philadelphia Orchestra's 'house arranger' and a

member

of its woodwind section, to provide a new orchestration of Pictures at an Exhibition

and he conducted its premiere on 5 February 1937, recording it for RCA

Victor later that same year.

However, Ormandy eventually returned to the Ravel arrangement and

recorded it three times (1953, 1966 and 1973).

Sir Georg Solti, KBE (21 October 1912 – 5 September 1997) was an orchestral and operatic conductor, best known for his appearances with opera companies in Munich, Frankfurt and London, and as a long serving music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Born in Hungary, he studied in Budapest with Béla Bartók, Leo Weiner and Ernő Dohnányi. In the 1930s, he was a répétiteur at the Hungarian State Opera and worked at the Salzburg Festival for Arturo Toscanini. His career was interrupted by the rise of the Nazis, and as a Jew he fled the increasingly restrictive anti - semitic laws in 1938. After conducting a season of Russian ballet in London at the Royal Opera House he found refuge in Switzerland, where he remained during the Second World War. He was not permitted to conduct there, but earned a living as a pianist.

After the war Solti was appointed musical director of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich from 1946. In 1952 he moved to the Frankfurt Opera, where he remained in charge for nine years. He took German citizenship in 1953. In 1961 he became musical director of the Covent Garden Opera Company in London, where in his ten year term he raised standards to the highest international levels. Under his musical directorship the status of the company was recognized with the grant of the title "the Royal Opera". He became a British subject in 1972.

In 1969 Solti took up his longest lasting appointment, as music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, a post he held for 22 years, becoming the orchestra's music director laureate on his retirement in 1991. He restored the orchestra's reputation after it had been in decline for most of the previous decade. During his time with the Chicago orchestra, he also had shorter spells in charge of the Orchestre de Paris and the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Known in his early years for the intensity of his music making, Solti was widely considered to have mellowed as a conductor in later years. He recorded many works two or three times at various stages of his career, and was a prolific recording artist, making more than 250 recordings, including 45 complete opera sets. The most famous of his recordings is probably Decca's complete set of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, made between 1958 and 1965. It has twice been voted the greatest recording ever made, in polls for Gramophone magazine in 1999 and the BBC's Music Magazine in 2012.

Solti was born György Stern (Hungarian: Stern György)

in Vérmező utca, in the Buda district of Budapest, the younger of the

two children of Móricz ("Mor") Stern and his wife Teréz, née

Rosenbaum.

In the aftermath of the First World War it became the accepted practice

in Hungary for citizens with Germanic surnames to adopt Hungarian ones.

A series of "Hungarianization" laws were passed by the right wing

regime of Admiral Horthy, including a requirement that state employees

with foreign sounding names must change them. Mor Stern, a self employed

merchant, felt no need to change his surname, but thought it prudent to

change that of his children. He renamed them after Solt, a small town in central Hungary. His son's given name, György, was acceptably Hungarian and was not changed.

Solti described his father as "a kind, sweet man who trusted everyone. He shouldn't have, but he did. Jews in Hungary were tremendously patriotic. In 1914, when war broke out, my father invested most of his money in a war loan to help the country. By the time the bonds matured, they were worthless." Mor Stern was a religious man, but his son was less so. Late in life Solti recalled, "I often upset him because I never stayed in the synagogue for longer than ten minutes." Teréz Stern was from a musical family, and encouraged her daughter Lilly, eight years the elder of the children, to sing, and György to accompany her at the piano. Solti remembered, "I made so many mistakes, but it was invaluable experience for an opera conductor. I learnt to swim with her." He was not a diligent student of the piano: "My mother kept telling me to practice, but what ten year old wants to play the piano when he could be out playing football?"

Solti enrolled at the Ernö Fodor School of Music in Budapest at the age of ten, transferring to the more prestigious Franz Liszt Academy two years later. When he was 12 he heard a performance of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony conducted by Erich Kleiber, which gave him the ambition to become a conductor. His parents could not afford to pay for years of musical education, and his rich uncles did not consider music a suitable profession; from the age of 13 Solti paid for his education by giving piano lessons.

The faculty of the Franz Liszt Academy included some of the most eminent Hungarian musicians, including Béla Bartók, Leo Weiner, Ernő Dohnányi and Zoltán Kodály. Solti studied under the first three, for piano, chamber music and composition respectively. Some sources state that he also studied with Kodály, but in his memoirs Solti recalled that Kodály, whom he would have preferred, turned him down, leaving him to study composition first with Albert Siklós and then with Dohnányi. Not all the Academy's tutors were equally distinguished: Solti remembered with little pleasure the conducting classes run by Ernö Unger, "who instructed his pupils to use rigid little wrist motions. I attended the class for only two years, but I needed five years of practical conducting experience before I managed to unlearn what he had taught me".

After graduating from the Academy in 1930 Solti was appointed to

the staff of the Hungarian State Opera. He found that working as a

répétiteur,

coaching singers in their roles and playing at rehearsals, was a more

fruitful preparation than Unger's classes for his intended career as a

conductor.

In 1932 he went to Karlsruhe in Germany as assistant to Josef Krips,

but within a year, Krips, anticipating the imminent rise to power of

Hitler and the Nazis, insisted that Solti should go home to Budapest,

where at that time Jews were not in danger.

Other Jewish and anti - Nazi musicians also left Germany for Budapest.

Among other musical exiles with whom Solti worked there were Otto Klemperer, Fritz Busch, and Kleiber. Before Austria fell under Nazi control, Solti was assistant to Arturo Toscanini at the 1937 Salzburg Festival:

Toscanini was the first great musical impression in my life. Before I heard him live in 1936, I had never heard a great opera conductor, not in Budapest, and it was like a lightning flash. I heard his Falstaff in 1936 and the impact was unbelievable. It was the first time I heard an ensemble singing absolutely precisely. It was fantastic. Then I never expected to meet Toscanini. It was a chance in a million. I had a letter of recommendation from the director of the Budapest Opera to the president of the Salzburg Festival. He received me and said: "Do you know Magic Flute, because we have an influenza epidemic and two of our repetiteurs are ill? Could you play this afternoon for the stage rehearsals?"

After further work as a répétiteur at the opera in Budapest, and with his standing enhanced by his association with Toscanini, Solti was given his first chance to conduct, on 11 March 1938. The opera was The Marriage of Figaro. During that evening, news came of the German invasion of Austria. Many Hungarians feared that Hitler would next invade Hungary; he did not do so, but Horthy, to strengthen his partnership with the Nazis, instituted anti - semitic laws, mirroring the Nuremberg Laws, restricting Hungary's Jews from engaging in professions. Solti's family urged him to move away. He went first to London, where he made his Covent Garden debut, conducting the London Philharmonic for a Russian ballet season. The reviewer in The Times was not impressed with Solti's efforts, finding them "too violent, for he lashed at the orchestra and flogged the music so that he endangered the delicate, evocative atmosphere." At about this time Solti dropped the name "György" in favor of "Georg".

After his appearances in London Solti went to Switzerland to seek out Toscanini, who was conducting in Lucerne. Solti hoped that Toscanini would help find him a post in the US. He was unable to do so, but Solti found work and security in Switzerland as vocal coach to the tenor Max Hirzel, who was learning the role of Tristan in Wagner's opera. Throughout the Second World War, Solti remained in Switzerland. He did not see his father again: Mor Stern died of diabetes in a Budapest hospital in 1943. Solti was reunited with his mother and sister after the war. In Switzerland he could not obtain a work permit as a conductor, but earned his living as a piano teacher. After he won the 1942 Geneva International Piano Competition he was permitted to give piano recitals, but was still not allowed to conduct. During his exile, he met Hedwig (Hedi) Oeschli, daughter of a lecturer at Zürich University. They married in 1946. In his memoirs he wrote of her, "She was very elegant and sophisticated. ... Hedi gave me a little grace and taught me good manners – although she never completely succeeded in this. She also helped me enormously in my career".

With the end of the war Solti's luck changed dramatically. He

was appointed musical director of the Bavarian State Opera in Munich in

1946.

In normal circumstances this prestigious post would have been an

unthinkable appointment for a young and inexperienced conductor, but the

leading German conductors such as Wilhelm Furtwängler, Clemens Krauss

and Herbert von Karajan were prohibited from conducting pending the

conclusion of denazification proceedings against them.

Under Solti's direction, the company rebuilt its repertoire and began

to recover its pre-war eminence. He benefited from the encouragement of

the elderly Richard Strauss, in whose presence he conducted Der Rosenkavalier. Strauss was reluctant to discuss his own music with Solti, but gave him advice about conducting.

In addition to the Munich appointment Solti gained a recording contract in 1946. He signed for Decca Records, not as a conductor but as a piano accompanist. He made his first recording in 1947, playing Brahms's First Violin Sonata with the violinist Georg Kulenkampff. He was insistent that he wanted to conduct, and Decca gave him his first recording sessions as a conductor later in the same year, with the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra in Beethoven's Egmont overture. Twenty years later Solti said, "I'm sure it's a terrible record, because the orchestra was not very good at that time and I was so excited. It is horrible, surely horrible – but by now it has vanished." He had to wait two years for his next recording as a conductor. It was in London, Haydn's Drum Roll symphony, in sessions produced by John Culshaw, with whose career Solti's became closely linked over the next two decades. Reviewing the record, The Gramophone said, "The performance of the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Georg Solti (a fine conductor who is new to me) is remarkable for rhythmic playing, richness of tone, and clarity of execution." The Record Guide compared it favorably with EMI's rival recording by Sir Thomas Beecham and the Royal Philharmonic.

In 1951 Solti conducted at the Salzburg Festival for the first time, partly through the influence of Furtwängler, who was impressed by him. The work was Idomeneo, which had not been given there before. In Munich Solti achieved critical and popular success, but for political reasons his position at the State Opera was never secure. The view persisted that a German conductor should be in charge; pressure mounted, and after five years Solti accepted an offer to move to Frankfurt in 1952 as musical director of the Frankfurt Opera. The city's opera house had been destroyed in the war, and Solti undertook to build a new company and repertoire for its recently completed replacement. He also conducted the symphony concerts given by the opera orchestra. Frankfurt was a less prestigious house than Munich and he initially regarded the move as a demotion. However, he found the post fulfilling and remained at Frankfurt from 1952 to 1961, presenting 33 operas, 19 of which he had not conducted before. Frankfurt, unlike Munich, could not attract many of the leading German singers. Solti recruited many rising young American singers such as Claire Watson and Sylvia Stahlman, to the extent that the house acquired the nickname "Amerikanische Oper am Main". In 1953 the West German government offered Solti German citizenship, which, being effectively stateless as a Hungarian exile, he gratefully accepted. He believed he could never return to Hungary, by then under communist rule. He remained a German citizen for two decades.

During his Frankfurt years Solti made appearances with other opera companies and orchestras. He conducted in the Americas for the first time in 1952, giving concerts in Buenos Aires. In the same year he made his debut at the Edinburgh Festival as a guest conductor with the visiting Hamburg State Opera. The following year he was a guest at the San Francisco Opera with Elektra, Die Walküre and Tristan und Isolde. In 1954 he conducted Don Giovanni at the Glyndebourne Festival. The reviewer in The Times said that no fault could be found in Solti's "vivacious and sensitive" conducting. In the same year Solti made his first appearance with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, at the Ravinia Festival.

In the recording studios Solti's career took off after 1956, when

John Culshaw was put in charge of Decca's classical recording program.

Culshaw believed Solti to be "the great Wagner conductor of our time", and was determined to record the four operas of Der Ring des Nibelungen with Solti and the finest Wagner singers available.

The cast Culshaw assembled for the cycle included Kirsten Flagstad,

Hans Hotter, Birgit Nilsson and Wolfgang Windgassen. Apart from Arabella

in 1957, in which he substituted when Karl Böhm withdrew, Solti had

made no complete recording of an opera until the sessions for Das Rheingold, the first of the Ring

tetralogy, in September and October 1958. In their respective memoirs

Culshaw and Solti told how Walter Legge of Decca's rival EMI predicted

that Das Rheingold would be a commercial disaster ("'Very nice,' he said, 'Very interesting. But of course you won't sell any.'") The success of the recording took the record industry by surprise. It featured for weeks in the Billboard

charts, the sole classical album alongside best sellers by Elvis

Presley and Pat Boone, and brought Solti's name to international

prominence. He appeared with leading orchestras in New York, Vienna and

Los Angeles, and at Covent Garden he conducted Der Rosenkavalier and Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream.

In 1960 Solti signed a three year contract to be music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic from 1962. Before he took up the post the Philharmonic's autocratic president Dorothy Chandler breached his contract by appointing a deputy music director without Solti's approval. Although he admired the chosen deputy, Zubin Mehta, Solti felt he could not have his authority undermined from the outset, and he withdrew from his appointment. He accepted an offer to become musical director of the Covent Garden Opera Company in London. When first sounded out about the post he had declined it. After 14 years of experience at Munich and Frankfurt he was uncertain that he wanted a third successive operatic post. Moreover, founded only 15 years earlier, the Covent Garden company was not yet the equal of the best opera houses in Europe. However, Bruno Walter convinced Solti that it was his duty to take Covent Garden on.

The biographer Montague Haltrecht suggests that Solti seized the breach of his Los Angeles contract as a convenient pretext to abandon the Philharmonic in favor of Covent Garden. However, in his memoirs Solti wrote that he wanted the Los Angeles position very much indeed. He originally considered holding both posts in tandem, but later acknowledged that he had had a lucky escape, as he could have done justice to neither post had he attempted to hold both simultaneously.

Solti took up the musical directorship of Covent Garden in August 1961.

The press gave him a cautious welcome, but there was some concern that

under him there might be a drift away from the company's original policy

of opera in English. Solti, however, was an advocate of opera in the

vernacular, and he promoted the development of British and Commonwealth

singers in the company, frequently casting them in his recordings and

important productions in preference to overseas artists. He demonstrated his belief in vernacular opera with a triple bill in English of L'heure espagnole, Erwartung and Gianni Schicchi.

As the decade went on, however, more and more productions had to be

sung in the original language to accommodate international stars.

Like his predecessor Rafael Kubelík, and his successor Colin Davis, Solti found his early days as musical director marred by vituperative hostility from a small clique in the Covent Garden audience. Rotten vegetables were thrown at him, and his car was vandalized outside the theater, with the words "Solti must go!" scratched on its paintwork. Some press reviews were strongly critical; Solti was so wounded by a review in The Times of his conducting of The Marriage of Figaro that he almost left Covent Garden in despair. The chief executive of the Opera House, Sir David Webster, persuaded him to stay with the company, and matters improved, helped by changes on which Solti insisted. The chorus and orchestra were strengthened, and in the interests of musical and dramatic excellence, Solti secured the introduction of the stagione system of scheduling performances, rather than the traditional repertory system. By 1967 The Times considered that "Patrons of Covent Garden today automatically expect any new production, and indeed any revival, to be as strongly cast as anything at the Met in New York, and as carefully presented as anything in Milan or Vienna".

The company's repertory in the 1960s combined the standard operatic works with less familiar pieces. Among the most celebrated productions during Solti's time in charge was Schoenberg's Moses and Aaron in the 1965 – 66 and 1966 – 67 seasons. In 1970, Solti led the company to Germany, where they gave Don Carlos, Falstaff and Victory, a new work by Richard Rodney Bennett. The public in Munich and Berlin were, according to the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, "beside themselves with enthusiasm".

Solti's bald head and demanding rehearsal style earned him the nickname "The Screaming Skull". A music historian called him "the bustling, bruising Georg Solti – a man whose entire physical and mental attitude embodied the words 'I'm in charge'." Singers such as Peter Glossop described him as a bully, and after working with Solti, Jon Vickers refused to do so again. Nevertheless, under Solti, the company was recognized as having achieved parity with the greatest opera houses in the world. Queen Elizabeth II conferred the title "the Royal Opera" on the company in 1968. By this point Solti was, in the words of his biographer Paul Robinson, "after Karajan, the most celebrated conductor at work". By the end of his decade as music director at Covent Garden Solti had conducted the company in 33 operas by 13 composers.

In 1964 Solti separated from his wife. He moved into the Savoy Hotel,

where not long afterwards he met Valerie Pitts, a British television

presenter, sent to interview him.

She too was married, but after pursuing her for three years, Solti

persuaded her to divorce her husband. Solti and Pitts married on 11

November 1967. They had two daughters.

In 1967 Solti was invited to become music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. It was the second time he had been offered the post. The first had been in 1963 after the death of the orchestra's conductor, Fritz Reiner, who made its reputation in the previous decade. Solti told the representatives of the orchestra that his commitments at Covent Garden made it impossible to give Chicago the eight months a year they sought. He suggested giving them three and a half months a year and inviting Carlo Maria Giulini to take charge for a similar length of time. The orchestra declined to proceed on these lines. When Solti accepted the orchestra's second invitation it was agreed that Giulini should be appointed to share the conducting. Both conductors signed three year contracts with the orchestra, effective from 1969.

One of the members of the Chicago Symphony described it to Solti as "the best provincial orchestra in the world." Many players remained from its celebrated decade under Reiner, but morale was low, and the orchestra was $5m in debt. Solti concluded that it was essential to raise the orchestra's international profile. He ensured that it was engaged for many of his Decca sessions, and he and Giulini led it in a European tour in 1971, playing in ten countries. It was the first time in its 80 year history that the orchestra had played outside the US. The orchestra received plaudits from European critics, and was welcomed home at the end of the tour with a ticker - tape parade.

The orchestra's principal flute player, Donald Peck, commented that

the relationship between a conductor and an orchestra is difficult to

explain: "some conductors get along with some orchestras and not others.

We had a good match with Solti and he with us."

Peck's colleague, the violinist Victor Aitay said, "Usually conductors

are relaxed at rehearsals and tense at the concerts. Solti is the

reverse. He is very tense at rehearsals, which makes us concentrate, but

relaxed during the performance, which is a great asset to the

orchestra.

Peck recalled Solti's constant efforts to improve his own technique and

interpretations, at one point experimentally dispensing with a baton,

drawing a "darker and deeper, much more relaxed" tone from the players.

As well as raising the orchestra's profile and helping it return to prosperity Solti considerably expanded its repertoire. Under him the Chicago Symphony gave its first cycles of the symphonies of Bruckner and Mahler. He introduced new works commissioned for the orchestra, such as Lutosławski's Third Symphony, and Tippett's Fourth Symphony, which was dedicated to Solti. Another new work was Tippett's Byzantium, an orchestral song cycle, premiered by Solti and the orchestra with the soprano Jessye Norman. Solti frequently programmed works by American composers, including Charles Ives and Elliott Carter.

Solti's recordings with the Chicago Symphony included the complete symphonies of Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner and Mahler. Most of his operatic recordings were with other orchestras, but his recordings of The Flying Dutchman (1976), Fidelio (1979), Moses und Aron (1984) and his second recordings of Die Meistersinger (1995) and Verdi's Otello (1991) were made with the Chicago players.

After retiring as music director in 1991 Solti continued to conduct the orchestra, and was given the title of music director laureate. He conducted 999 concerts with the orchestra. His 1,000th concert was scheduled for October 1997, around the time of his 85th birthday.

In addition to his tenure in Chicago Solti was music director of the Orchestre de Paris from 1972 to 1975.

From 1979 until 1983 he was also principal conductor of the London

Philharmonic Orchestra. He continued to expand his repertoire. With the

London Philharmonic he performed many of Elgar's major works in concert

and on record.

Before performing Elgar's two symphonies, Solti studied the composer's

own recordings made more than 40 years earlier, and was influenced by

their brisk tempi and impetuous manner. A critic in The Guardian wrote that Solti "conveys the authentic frisson of the great Elgarian moment more vividly than ever before on record."

Late in his career he became enthusiastic about the music of

Shostakovich, whom he admitted he failed to appreciate fully during the

composer's lifetime. He made commercial recordings of seven of

Shostakovich's fifteen symphonies.

In 1983 Solti conducted for the only time at the Bayreuth Festival. By this stage in his career he no longer liked abstract productions of Wagner, or modernistic reinterpretations, such as Patrice Chéreau's 1976 Bayreuth Ring, which he found grew boring on repetition. Together with the director Sir Peter Hall and the designer William Dudley, he presented a Ring cycle that aimed to represent Wagner's intentions. The production was not well received by German critics, who expected radical reinterpretation of the operas. Solti's conducting was praised, but illnesses and last minute replacements of leading performers affected the standard of singing. He was invited to return to Bayreuth for the following season, but was unwell and withdrew on medical advice before the 1984 festival began.

In 1991 Solti collaborated with the actor and composer Dudley Moore to create an eight part television series, Orchestra!, which was designed to introduce audiences to the symphony orchestra. In 1994 he directed the "Solti Orchestral Project" at Carnegie Hall, a training workshop for young American musicians. The following year, to mark the 50th anniversary of the United Nations, he formed the World Orchestra for Peace, which consisted of 81 musicians from 40 nations. The orchestra has continued to perform after his death, under the conductorship of Valery Gergiev.

Solti regularly returned to Covent Garden as a guest conductor in the years after he relinquished the musical directorship, greeted with "an increasingly boisterous hero's welcome". From 1972 to 1997 he conducted ten operas, some of them in several seasons. Five were operas he had not conducted at the Royal Opera House before: Carmen, Parsifal, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Simon Boccanegra and a celebrated production of La traviata (1994) which propelled Angela Gheorghiu to stardom. On 14 July 1997 he conducted the last operatic music to be heard in the old house before it closed for more than two years for rebuilding. The previous day he had conducted what proved to be his last symphony concert. The work was Mahler's Fifth Symphony; the orchestra was the Zurich Tonhalle, with whom he had made his first orchestral recording 50 years earlier.

Solti died suddenly, in his sleep, on 5 September 1997 while on

holiday in Antibes in the south of France. He was 84. After a state

ceremony in Budapest, his ashes were interred beside the remains of

Bartók in Farkasréti Cemetery.

Solti recorded throughout his career for the Decca Record Company. He made more than 250 recordings, including 45 complete opera sets. During the 1950s and 1960s Decca had an alliance with RCA Records, and some of Solti's recordings were first issued on the RCA label.

Solti was one of the first conductors who came to international fame as a recording artist before being widely known in the concert hall or opera house. Gordon Parry, the Decca engineer who worked with Solti and Culshaw on the Ring recordings, observed, "Many people have said 'Oh well, of course John Culshaw made Solti.' This is not true. He gave him the opportunity to show what he could do."

Solti's first recordings were as a piano accompanist, playing at sessions in Zurich for the violinist Georg Kulenkampff in 1947. Decca's senior producer, Victor Olof did not much admire Solti as a conductor (nor did Walter Legge, Olof's opposite number at EMI's Columbia Records), but Olof's younger colleague and successor, Culshaw, held Solti in high regard. As Culshaw, and later James Walker, produced his recordings, Solti's career as a recording artist flourished from the mid 1950s. Among the orchestras with whom Solti recorded were the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the London Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, London Symphony and Berlin Philharmonic orchestras. Soloists in his operatic recordings included Joan Sutherland, Régine Crespin, Plácido Domingo, Gottlob Frick, Carlo Bergonzi, Kiri Te Kanawa and José van Dam. In concerto recordings, Solti conducted for, among others, Julius Katchen, Clifford Curzon, Vladimir Ashkenazy and Kyung - Wha Chung.

Solti's most celebrated recording was Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen

made in Vienna, produced by Culshaw, between 1958 and 1965. It has

twice been voted the greatest recording ever made, the first poll being

among readers of Gramophone magazine in 1999, and the second of professional music critics in 2011, for the BBC's Music Magazine.

Honors awarded to Solti included the British CBE (honorary), 1968, and an honorary knighthood (KBE), 1971, which became a substantive knighthood when he took British citizenship in 1972, after which he was known as Sir Georg Solti. He received honors from other countries, including Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Portugal and the US. He received honorary fellowships or degrees from the Royal College of Music and Baden - Württemberg, DePaul, Furman, Harvard, Leeds, London, Oxford, Surrey and Yale universities.

In celebration of his 75th birthday in 1987, a bronze bust of Solti by Dame Elisabeth Frink was dedicated in Lincoln Park, Chicago, outside the Lincoln Park Conservatory. The bust was first displayed temporarily at London's Royal Opera House. Frink, one of Britain's foremost 20th century sculptors, here "demonstrate[s] her extraordinary talent," although, it is perhaps Solti "in his severest glaring mode." The sculpture was moved to Grant Park in 2006, placed in a new Solti Garden, near Orchestra Hall in Symphony Center. In 1997, to commemorate the 85th anniversary of his birth, the City of Chicago renamed the block of East Adams Street adjacent to Symphony Center as "Sir Georg Solti Place" in his memory.

Record industry awards to Solti included the Grand Prix Mondiale du Disque (14 times) and 32 Grammy Awards (including a special Trustees' Grammy Award for his recording of the Ring and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award). He won more Grammys than any other recording artist, whether classical or popular. In September 2007, as a tribute on the 10th anniversary of his death, Decca published a recording of his final concert.

After Solti's death his widow and daughters set up the Solti Foundation to assist young musicians. Solti's memoirs, written with the assistance of Harvey Sachs, were published the month after his death. They appeared in the UK under the title Solti on Solti, and in the US as Memoirs. Solti's life was also documented in a 1997 film by Peter Maniura, Sir Georg Solti: The Making of a Maestro. In 2007 Valerie Solti was appointed a Cultural Ambassador of Hungary, an honorary title granted by the Hungarian state.

In 2012 a series of events under the banner of "Solti @ 100" was announced, to mark the centenary of Solti's birth. Among the events announced were concerts in New York and Chicago, and commemorative exhibitions in London, Chicago, Vienna and New York.