<Back to Index>

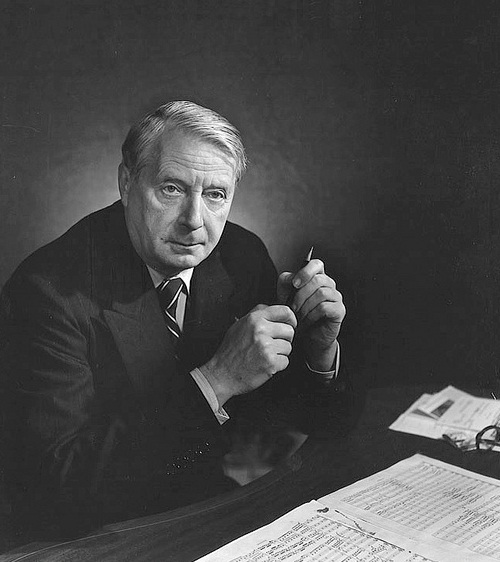

- Conductor and Violinist Charles Münch, 1891

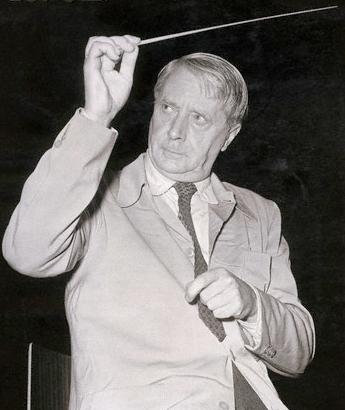

- Conductor Seiji Ozawa, 1935

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles Munch (born Charles Münch) (September 26, 1891 – November 6, 1968) was an Alsatian symphonic conductor and violinist. Noted for his mastery of the French orchestral repertoire, he is best known as music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Munch was born in Strasbourg, Alsace - Lorraine, German Empire (now France, since 1919). The son of organist and choir director Ernst Münch, he was the fifth in a family of six children. He was the brother of conductor Fritz Münch and the cousin of conductor and composer Hans Münch. Although his first ambition was to be a locomotive engineer, he studied violin at the Strasbourg Conservatoire. His father Ernst was a professor of organ at the Conservatoire and performed at the cathedral; he also directed an orchestra with his son Charles in the second violins.

After receiving his diploma in 1912, Charles studied with Carl Flesch in Berlin and Lucien Capet at the Conservatoire de Paris. He was conscripted into the German army in World War I, serving as a sergeant gunner. He was gassed at Péronne and wounded at Verdun.

In 1920, he became professor of violin at the Strasbourg Conservatoire and assistant concertmaster of the Strasbourg Philharmonic Orchestra under Joseph Guy Ropartz, who directed the conservatory. In the early 1920s he was concertmaster for Hermann Abendroth's Gürzenich Orchestra in Cologne. He then served as concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra under Wilhelm Furtwängler and Bruno Walter from 1926 to 1933.

At the age of 41, Munch made his conducting debut in Paris on November 1, 1932. Munch's fiancée, Geneviève Maury, granddaughter of a founder of the Nestlé Chocolate Company, rented the hall and hired the Walther Straram Concerts Orchestra. She was also an accomplished translator of Thomas Mann. Munch also studied conducting with Czech conductor Fritz Zweig who had fled Berlin during his tenure at Berlin's Krolloper.

Following this success, he conducted the Concerts Siohan, the Lamoureux Orchestra, the new Orchestre Symphonique de Paris, the Biarritz Orchestra (Summer 1933), the Société Philharmonique de Paris (1935 to 1938), and the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire (1937 to 1946). He became known as a champion of Hector Berlioz, and befriended Arthur Honegger, Albert Roussel, and Francis Poulenc. During these years, Munch gave first performances of works by Honegger, Jean Roger - Ducasse, Joseph Guy Ropartz, Roussel, and Florent Schmitt. He became director of the Société Philharmonique de Paris in 1938 and taught conducting at the Conservatoire de Paris from 1937 to 1945.

He remained in France conducting the Conservatoire Orchestra during the German occupation,

believing it best to maintain the morale of the French people. He

refused conducting engagements in Germany and also refused to perform

contemporary German works. He protected members of his orchestra from

the Gestapo and contributed from his income to the French Resistance. For this, he received the Légion d'honneur with the red ribbon in 1945 and the degree of Commandeur in 1952.

Munch made his début with the Boston Symphony Orchestra on December 27, 1946. He was its Music Director from 1949 to 1962. Munch was also Director of the Berkshire Music Festival and Berkshire Music Center (Tanglewood) from 1951 through 1962. He led relaxed rehearsals which orchestra members appreciated after the authoritarian Serge Koussevitzky. Munch also received honorary degrees from Boston College, Boston University, Brandeis University, Harvard University, and the New England Conservatory of Music.

He excelled in the modern French repertoire, especially Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, and was considered to be an authoritative performer of Hector Berlioz. However, Munch's programs also regularly featured works by composers such as Bach, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, and Wagner. His thirteen year tenure in Boston included 39 world premieres and 58 American first performances, and offered audiences 168 contemporary works. Fourteen of these premieres were works commissioned by the Boston Symphony and the Koussevitzky Music Foundation to celebrate the Orchestra's 75th Anniversary in 1956. (A 15th commission was never completed.)

Munch invited former Boston Symphony music director Pierre Monteux to guest conduct, record, and tour with the orchestra after an absence of more than 25 years. Under Munch, guest conductors became an integral part of the Boston Symphony's programming, both in Boston and at Tanglewood.

Munch led the Boston Symphony on its first transcontinental tour of the United States in 1953. He became the first conductor to take them on tour overseas: Europe in 1952 and 1956, and East Asia and Australia in 1960. During the 1956 tour, the Boston Symphony was the first American orchestra to perform in the Soviet Union.

The Boston Symphony under Munch made a series of recordings for RCA Victor from 1949 to 1953 in monaural sound and from 1954 to 1962 in both monaural and stereophonic versions.

Selections from Boston Symphony rehearsals under Leonard Bernstein, Koussevitzky, and Munch were broadcast nationally on the NBC Radio Network from 1948 - 1951. NBC carried portions of the Orchestra's performances from 1955 - 1957. Beginning in 1951, the BSO was broadcast over local radio stations in the Boston area. Starting in 1957, Boston Symphony performances under Munch and guest conductors were disseminated regionally, nationally, and internationally through the Boston Symphony Transcription Trust. And, under Munch, the Boston Symphony first appeared on television.

Munch returned to France and in 1963 became president of the École Normale de Musique. He was also named president of the Guilde Française des Artistes Solistes.

During the 1960s, Munch appeared regularly as a guest conductor

throughout America, Europe, and Japan. In 1967, at the request of

France's Minister of Culture, André Malraux, he founded the first full time salaried French orchestra, the Orchestre de Paris, and conducted its first concert on November 14, 1967. The following year, he died of a heart attack suffered at his hotel in Richmond, Virginia, while on an American tour with his new orchestra. His remains were returned to France where he is buried in the Cimetière de Louveciennes. EMI recorded his final sessions, including Ravel's Piano Concerto in G, with this orchestra, and released them posthumously.

In 1955, Oxford University Press published "I Am a Conductor" by Munch in a translation by Leonard Burkat. It was originally issued in 1954 in French as "Je suis chef d'orchestre." The work is a collection of Munch's thoughts on conducting and the role of a conductor.

D. Kern Holoman wrote Munch's first biography in English, "Charles Munch." It was published by Oxford University Press in 2011.

Munch's discography is extensive, both in Boston on RCA Victor and at his various European posts and guest conducting assignments on various labels, including English Decca, EMI, Nonesuch, Erato and Audivis - Valois.

He began making records in Paris before the war, for EMI. Munch then made a renowned series of Decca Full Frequency Range Recordings (FRRR) in the late 1940s. After several recordings with the New York Philharmonic for Columbia, Munch began making recordings for RCA Victor soon after his arrival in Boston as Music Director. These included memorable Berlioz, Honegger, Roussel, and Saint - Saëns tapings.

His first stereophonic recording with the Boston Symphony, in Boston's Symphony Hall in February 1954, was devoted to a complete version of The Damnation of Faust by Hector Berlioz and was made simultaneously in monaural and experimental stereophonic sound, although only the complete score was released in monaural version. The stereo tape survives only fragmentarily. The monaural version of this recording was added to the Library of Congress's national registry of sound. Among his final recordings in Boston was a 1962 performance of César Franck's symphonic poem Le chasseur maudit.

Upon Munch's return to Paris, he made Erato disks with the Orchestre Lamoureux, and with the Orchestre de Paris he again recorded for EMI. He also made recordings for a number of other companies including Decca / London.

A number of Munch's recordings have been available continuously since their original releases such as Saint - Saëns's Organ Symphony and Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe. RCA reissued Munch Conducts Berlioz in a multi - disc set, including everything they had. BMG / Japan has issued two different editions of Munch's recordings on CD, 1998 and 2006. The latter was 41 CDs and encompassed all but a handful of Munch recordings with the Boston Symphony. It made available a number of recordings from the first ten years of Munch's tenure in Boston for the first time in more than 50 years.

The Boston Symphony appeared on television with Munch locally on WGBH-TV, Boston, and nationally through a syndicated series. NHK

broadcast throughout Japan the opening concert of the Boston Symphony's

tour of Japan in 1960. Munch also appeared on film or television with

the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Czech Philharmonic, the Hungarian

Radio and Television Orchestra, the Orchestre National de l'ORTF, and

the Orchestre de Radio - Canada.

Seiji Ozawa (小澤 征爾 Ozawa Seiji, born September 1, 1935) is a Japanese conductor, particularly noted for his interpretations of large scale late Romantic works. He is most known for his work as music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and principal conductor of the Vienna State Opera.

Seiji Ozawa was born on September 1, 1935 to Japanese parents in the city of Mukden, Manchukuo, in what is now northeastern China. When his family returned to Japan in 1944, he began studying piano with Noboru Toyomasu, heavily studying the works of Johann Sebastian Bach. After graduating from the Seijo Junior High School in 1950, Ozawa sprained his finger in a rugby game. Unable to continue studying the piano, his teacher at the Toho Gakuen School of Music (Hideo Saito), brought Ozawa to a life changing performance of Beethoven's Symphony No. 5, which ultimately shifted his musical focus from piano performance to conducting.

Almost a decade after the sports injury, Ozawa won the first prize at the International Competition of Orchestra Conductors in Besançon, France. His success in France led to an invitation by Charles Münch, then the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, to attend the Berkshire Music Center (now the Tanglewood Music Center). In 1960, shortly after his arrival, Ozawa won the Koussevitzky Prize for outstanding student conductor, Tanglewood's highest honor. Receiving a scholarship to study conducting with famous Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan, Ozawa moved to West Berlin. Under the tutelage of von Karajan, Ozawa caught the attention of prominent conductor Leonard Bernstein. Bernstein then appointed him as assistant conductor of the New York Philharmonic where he remained for the next four years. While with the New York Philharmonic, he made his first professional concert appearance with the San Francisco Symphony in 1962.

In December 1962 Ozawa was involved in a controversy with the prestigious Japanese NHK Symphony Orchestra when certain players, unhappy with his style and personality, refused to play under him. Ozawa went on to conduct the rival Japan Philharmonic Orchestra instead. From 1964 to 1971, Seiji Ozawa served as the first music director of the Ravinia Festival, the summer home of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

He was music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra from 1965 to 1970 and of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra from 1969 to 1976. In 1972, he led the San Francisco Symphony in its

first commercial recordings in a decade, recording music inspired by William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet.

In 1973, he took the San Francisco orchestra on a European tour, which

included a Paris concert that was broadcast via satellite in stereo to

San Francisco station KKHI. He left San Francisco after a dispute with a players committee over granting tenure

to two young musicians Ozawa had selected. From 1977 to 1979, he was

the resident conductor for the Singapore Philharmonic Orchestra. He

returned to San Francisco as a guest conductor, including a 1978 concert

featuring music from Tchaikovsky's ballet Swan Lake.

Between the years of 1964 and 1973, he directed various orchestras until he became music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1973. His tenure at the BSO was maintained for 29 years, the longest tenure of any music director, surpassing the 25 years held by Serge Koussevitzky. Ozawa won his first Emmy Award in 1976, for the Boston Symphony Orchestra's PBS television series, "Evening at Symphony." In 1994, the BSO dedicated its new Tanglewood concert hall "Seiji Ozawa Hall" in honor of his 20th season with the orchestra. In 1994, he was awarded his second Emmy for Individual Achievement in Cultural Programming for "Dvořák in Prague: A Celebration."

An effort to merge all Japanese orchestras and performers with international artists, Ozawa, along with Kazuyoshi Akiyama, founded the Saito Kinen Orchestra in 1992. Since its creation, the orchestra has gained a prominent position in the international music community. In the same year, he also made his debut with the Metropolitan Opera in New York. He has additionally conducted the Berlin Philharmonic and Vienna Philharmonic on a regular basis. Ozawa can be seen in concert with the New Japan Philharmonic, the London Symphony, the Orchestre National de France, La Scala in Milan and the Vienna Staatsoper.

Ozawa caused controversy from 1996 – 1997 with sudden demands for change at the Tanglewood Music Center, which caused Gilbert Kalish and Leon Fleisher to resign in protest. Toward the end of Ozawa's tenure, he received strong criticism from the American critic and composer Greg Sandow, which led to controversy in the Boston press. Other critical commentary on Ozawa's tenure in Boston has been aired.

Ozawa has been an advocate of 20th century classical music, giving the premieres of a number of works including György Ligeti's San Francisco Polyphony in 1975 and Olivier Messiaen's opera Saint François d'Assise

in 1983. He is noted to have somewhat of a photographic memory, as he

is able to memorize the scores of large works such as the Mahler

Symphonies.

In 2001, Ozawa was recognized by the Japanese government as a Person of Cultural Merit.

In 2002, he continued to follow in Herbert von Karajan's footsteps, as he became principal conductor of the Vienna State Opera. Ozawa continues to play a key role as a teacher and administrator at the Tanglewood Music Center, the Boston Symphony Orchestra's summer music home that has programs for young professionals and high school students.

On New Year's Day 2002, Ozawa conducted an all Strauss concert with the Vienna Philharmonic, programming the concert so it would have a nice flow and keep everyone's interest as they ushered in the New Year. In 2005, he conducted the Tokyo Opera Nomori's debut of Richard Strauss’ Elektra. Ozawa has received a significant amount of criticism, especially from Boston music critic Greg Sandow, as he reports that some BSO members claim that Ozawa gives "no specific leadership in matters of tempo and rhythm", providing no "expression of care about sound quality." Despite the criticism, Ozawa serves a musical role model: an Asian performer who has not only attained fame in the West but has also devoted his life to fostering a global community within classical music.

On February 1, 2006, the Vienna State Opera announced that he had to cancel all his 2006 conducting engagements because of illness, including pneumonia and shingles. He returned to conducting in March 2007 at the Tokyo Opera Nomori.

Ozawa stepped down from his post at the Vienna State Opera in 2010, to be succeeded by Franz Welser - Möst.

In October 2008, Ozawa was honored with Japan's Order of Culture; and an awards ceremony for the Order of Culture will be held at the Imperial Palace. He is a recipient of the 34th Suntory Music Award (2002) and the International Center in New York's Award of Excellence.

On January 7, 2010, Ozawa announced that he was canceling all engagements for six months in order to undergo treatments for esophageal cancer. The doctor with Ozawa at the time of the announcement said it was detected at an early stage.

He returned to work on July 26, 2010, but promptly suffered further setbacks with a lumbar hernia. In August 2011 he conducted Bartok's Blubeard's Castle with the Saito Kinen orchestra in Matsumoto, prior to a tour of China. After a single, successful performance, he withdrew once more with pneumonia. Doctors were hopeful of a prompt recovery.

Seiji Ozawa holds honorary doctorate degrees from Harvard University, the New England Conservatory, the University of Massachusetts, and Wheaton College.

Ozawa became famous not only for his conducting mannerisms, but also his sartorial style: he wore the traditional formal dress with a white turtleneck rather than the usual starched shirt, waistcoat, and white tie.