<Back to Index>

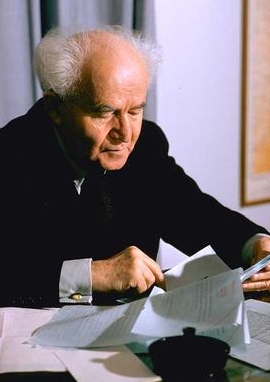

- 1st Prime Minister of Israel David Ben - Gurion, 1886

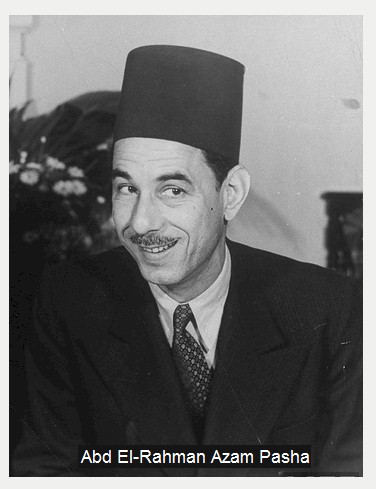

- 1st Secretary General of the Arab League Abdul Rahman Hassan Azzam, 1893

PAGE SPONSOR

David Ben-Gurion (Hebrew: דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן, Arabic: دافيد بن غوريون Dafeed Bin Ghuriyyun, born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was a founder and the first Prime Minister of Israel.

Ben-Gurion's passion for Zionism, which began early in life, led him to become a major Zionist leader and Executive Head of the World Zionist Organization in 1946. As head of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, and later president of the Jewish Agency Executive, he became the de facto leader of the Jewish community in Palestine, and largely led the struggle for an independent Jewish state in Palestine. On 14 May 1948, he formally proclaimed the establishment of the State of Israel, and was the first to sign the Israeli Declaration of Independence. Ben-Gurion led the provisional government of Israel during the 1948 Arab - Israeli War, and united the various Jewish militias into the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

Following the war, Ben Gurion served as Israel's first Prime Minister. As Prime Minister, he helped build the state institutions, presiding over various national projects aimed at the development of the country. He also oversaw the absorption of vast numbers of Jews from all over the world. A centerpiece of his foreign policy was improving relationships with the West Germans. He worked very well with Konrad Adenauer's government in Bonn and West Germany provided large sums in compensation for Germany's mistreatment of Jews in the Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany.

In 1954, he resigned and served as Minister of Defense, before returning to office in 1955. Under his leadership, Israel responded aggressively to Arab guerilla attacks, and in 1956, invaded Egypt along with British and French forces after Egypt nationalized the Suez Canal.

He stepped down from office in 1963, and retired from political life

in 1970. He then moved to Sde Boker, a kibbutz in the Negev desert,

where he lived until his death. Posthumously, Ben-Gurion was named one

of Time magazine's 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century.

David Ben Gurion was born in Płońsk, Congress Poland, which was then part of the Russian Empire. His father, Avigdor Grün, was a lawyer and a leader in the Hovevei Zion movement. His mother, Scheindel, died when he was 11 years old. Aged 14 he and two friends formed a youth club, Ezra, promoting Hebrew studies and emigration to the Holy Land.

In 1905, as a student at the University of Warsaw, he joined the Social - Democratic Jewish Workers' Party - Poalei Zion. He was arrested twice during the Russian Revolution

of 1905. In 1906 he emigrated to Ottoman Palestine. A month after his

arrival he was elected to the central committee of the newly formed

branch of Poali Zion in Jaffa,

becoming chairman of the party's platform committee. He advocated a

more nationalist program than other more leftist / Marxist members of

the

committee. The following year he complained about the Russian domination

of the group. At the time the Jewish population in Palestine was around

55,000 - of whom 40,000 held Russian citizenship.

In 1907, having been working picking oranges at Petah Tikvah, Ben Gurion moved to the settlements in Galilee where he worked as an agricultural laborer and withdrew from politics. In 1908 he joined an armed group acting as watchmen at Sejera.

On 12 April 1909, following an attempted robbery in which an Arab from Kfar Kanna was killed, Ben Gurion was involved in fighting in which one of the watchmen and a farmer from Sejera were killed.

In 1909 he volunteered with HaShomer, a force of volunteers who helped guard isolated Jewish agricultural communities. On 7 November 1911, Ben Gurion arrived in Thessaloniki in order to learn Turkish for his law studies. The city, which had a large Jewish community, impressed Ben Gurion who called it "a Jewish city that has no equal in the world." He also realized there that "the Jews were capable of all types of work," from rich businessmen and professors, to merchants, craftsmen and porters.

In 1912, he moved to Istanbul, the Ottoman capital, to study law at

Istanbul University together with Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, and adopted the

Hebrew name Ben-Gurion, after the medieval historian Yosef ben Gurion.

He also worked as a journalist. Ben Gurion saw the future as dependent

on the Ottoman regime. He was living in Jerusalem at the start of the First World War

where he and Ben Zvi recruited forty Jews into a Jewish militia to

assist the Ottoman Army. Despite this he was deported to Egypt in March

1915. From there he made his way to the United States where he remained

for three years. On his arrival he and Ben Zvi went on a tour of 35

cities in an attempt to raise a pioneer army, Hechalutz, of 10,000 men

to fight on Turkey's side. Settling in New York City in 1915, he met

Russian born Paula Munweis. They were married in 1917, and had three

children. He joined the British Army in 1918 as part of the 38th

Battalion of the Jewish Legion (following the Balfour Declaration in

November 1917). He and his family returned to Palestine after World War I

following its capture by the British from the Ottoman Empire.

After the death of theorist Ber Borochov, the left wing and right wing of Poale Zion split in 1919 with Ben Gurion and his friend Berl Katznelson leading the right faction of the Labor Zionist movement. The Right Poale Zion formed Ahdut HaAvoda with Ben Gurion as leader in 1919. In 1920 he assisted in the formation and subsequently became general secretary of the Histadrut, the Zionist Labor Federation in Palestine. At Ahdut HaAvoda's 3rd Congress, held in 1924 at Ein Harod, Shlomo Kaplansky, a veteran leader from Poalei Zion, proposed that the party should support British Mandatory authorities plans for setting up an elected legislative council in Palestine. He argued that a Parliament, even with an Arab majority, was the way forward. Ben Gurion, already emerging as the leader of the Yishuv, succeeded in getting Kaplansky's ideas rejected.

In 1930, Hapoel Hatzair (founded by A.D. Gordon in 1905) and Ahdut HaAvoda joined forces to create Mapai, the more right wing Zionist labor party (it was still a left wing organization, but not as far left as other factions) under Ben Gurion's leadership. In the 1940s the left wing of Mapai broke away to form Mapam. Labor Zionism became the dominant tendency in the World Zionist Organization and in 1935 Ben Gurion became chairman of the executive committee of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, a role he kept until the creation of the state of Israel in 1948.

Ben Gurion believed that the sparsely populated and barren Negev desert offered a great opportunity for the Jews to settle in Palestine with minimal obstruction of the Arab population, and set a personal example by settling in kibbutz Sde Boker at the center of the Negev.

During the 1936 – 1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, Ben Gurion instigated a policy of restraint ("Havlagah") in which the Haganah and other Jewish groups did not retaliate for Arab attacks against Jewish civilians, concentrating only on self defense. In 1937, the Peel Commission recommended partitioning Palestine into Jewish and Arab areas and Ben Gurion supported this policy. This led to conflict with Ze'ev Jabotinsky who opposed partition and as a result Jabotinsky's supporters split with the Haganah and abandoned Havlagah.

The Ben Gurion House, where he lived from 1931 on, and for part of each year after 1953, is now a museum in Tel Aviv.

Ben Gurion published two volumes setting out his views on relations between Zionists and the Arab world: We and Our Neighbors, published in 1931, and My Meetings with Arab Leaders published in 1967.

Ben Gurion believed in the equal rights of Arabs who remained in and would become citizens of Israel. He was quoted as saying, "We must start working in Jaffa. Jaffa must employ Arab workers. And there is a question of their wages. I believe that they should receive the same wage as a Jewish worker. An Arab has also the right to be elected president of the state, should he be elected by all."

Ben Gurion recognized the strong attachment of Palestinian Arabs to the land but hoped that this would be overcome in time. In an address to the United Nations and the British Mandate, he also doubted the likelihood of peace with the future Arab nations:

This is our native land; it is not as birds of passage that we return to it. But it is situated in an area engulfed by Arabic speaking people, mainly followers of Islam. Now, if ever, we must do more than make peace with them; we must achieve collaboration and alliance on equal terms. Remember what Arab delegations from Palestine and its neighbors say in the General Assembly and in other places, talk of Arab - Jewish amity sound fantastic, for the Arabs do not wish it, they will not sit at the same table with us, they want to treat us as they do the Jews of Bagdad, Cairo, and Damascus.

Nahum Goldmann criticized Ben Gurion for what he viewed as Ben Gurion's confrontational approach to the Arab world. Goldmann wrote that "Ben Gurion is the man principally responsible for the anti - Arab policy, because it was he who molded the thinking of generations of Israelis."

The view that Ben Gurion's assessment of Arab feelings led him to emphasize the need to build up Jewish military strength is supported by Simha Flapan, who quoted Ben Gurion as stating in 1938: "I believe in our power, in our power which will grow, and if it will grow agreement will come..."

In 1909 Ben Gurion attempted to learn Arabic but gave up. He later

became fluent in Turkish. The only other languages he was able to use

when in discussions with Arab leaders were English, and to a lesser

extent, French.

The British 1939 White paper stipulated that Jewish immigration to Palestine was to be limited to 15,000 a year for the first five years, and would subsequently be contingent on Arab consent. Restrictions were also placed on the rights of Jews to buy land from Arabs. After this Ben Gurion changed his policy towards the British, stating: "Peace in Palestine is not the best situation for thwarting the policy of the White Paper". Ben Gurion believed a peaceful solution with the Arabs had no chance and soon began preparing the Yishuv for war. According to Teveth 'through his campaign to mobilize the Yishuv in support of the British war effort, he strove to build the nucleus of a "Hebrew army", and his success in this endeavor later brought victory to Zionism in the struggle to establish a Jewish state.'

During the Second World War, Ben Gurion encouraged the Jews of Palestine to volunteer for the British Army. He famously told Jews to "support the British as if there is no White Paper and oppose the White Paper as if there is no war". About 10% of the Jewish population of Palestine volunteered for the British Army, including many women. At the same time Ben Gurion assisted the illegal immigration of thousands of European Jewish refugees to Palestine during a period when the British placed heavy restrictions on Jewish immigration.

In 1946, Ben Gurion agreed that the Haganah could cooperate with Menachem Begin's Irgun in fighting the British, who continued to restrict Jewish immigration. Ben Gurion initially agreed to Begin's plan to carry out the 1946 King David Hotel bombing, with the intent of embarrassing (rather than killing) the British military stationed there. However, when the risks of mass killing became apparent, Ben Gurion told Begin to call the operation off; Begin refused.

Illegal Jewish migration led to pressure on the British to either allow Jewish migration (as required by the League of Nations Mandate) or quit – they did the latter in 1948, not changing their restrictions,

on the heels of a United Nations resolution partitioning the territory

between the Jews and Arabs.

Ben Gurion had stated to the Mapai Council on 8 February 1948 that "From your entry into Jerusalem, through Lifta, Romema [East Jerusalem]. . . there are no Arabs. One hundred percent Jews. Since Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans, it has not been Jewish as it is now. In many Arab neighborhoods in the west one sees not a single Arab. I do not assume that this will change. . . . What had happened in Jerusalem. . . . is likely to happen in many parts of the country. . . in the six, eight, or ten months of the campaign there will certainly be great changes in the composition of the population in the country." (Benny Morris, Expulsion of the Palestinians)

He had also stated in a speech addressing the Zionist Action

Committee regarding the 'Arab Demographic Problem' that "We will not be

able to win the war if we do not, during the war, populate upper and

lower, eastern and western Galilee, the Negev and Jerusalem area, even

if only in an artificial way, in a military way. . . . I believe that

war will also bring in its wake a great change in the distribution of

Arab population."

In September 1947 Ben Gurion reached a status quo agreement with the Orthodox Agudat Yisrael party. He sent a letter to Agudat Yisrael stating that while he is committed to establishing a non-theocratic state with freedom of religion he is promising that Shabbat would be Israel's official day of rest, that in State provided kitchens there will be access to Kosher food, that every effort will be made to provide a single jurisdiction for Jewish family affairs, and that each sector would be granted autonomy in the sphere of education, provided minimum standards regarding the curriculum are observed.

To a large extent this letter (or agreement) provided a framework for

religious affairs in Israel (e.g., no civil marriages, just as in

Mandate times) and is often a benchmark to which the status is compared.

During the 1948 Arab - Israeli War Ben Gurion oversaw the nascent state's military operations. During the first weeks of Israel's independence, he ordered all militias to be replaced by one national army, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). To that end, Ben Gurion used a firm hand during the Altalena Affair, a ship carrying arms purchased by the Irgun. He insisted that all weapons be handed over to the IDF. When fighting broke out on the Tel Aviv beach he ordered it be taken by force and to shell the ship. Sixteen Irgun fighters and three IDF soldiers were killed in this battle. Following the policy of a unified military force, he also ordered that the Palmach headquarters be disbanded and its units be integrated with the rest of the IDF, to the chagrin of many of its members. His attempts to reduce the number of Mapam members in the senior ranks led to the "Generals' Revolt" in June 1948.

As head of the Jewish Agency,

Ben Gurion was de facto leader of Palestine's Jews even before the

state was declared. In this position, Ben Gurion played a major role in

the 1948 Arab Israeli War and the resulting Palestinian exodus.

When the IDF archives and others were opened in the late 1980s,

scholars started to reconsider the events and the role of Ben Gurion.

On 14 May, on the last day of the British Mandate, Ben Gurion declared the independence of the state of Israel. In the Israeli declaration of independence, he stated that the new nation would "uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens, without distinction of religion, race."

In his War Diaries in February 1948, Ben Gurion wrote: "The war shall

give us the land. The concepts of 'ours' and 'not ours' are peace

concepts only, and they lose their meaning during war."

Also later he confirmed this by stating that, "In the Negev we shall

not buy the land. We shall conquer it. You forget that we are at war."

After leading Israel during the 1948 Arab - Israeli War, Ben Gurion was elected Prime Minister of Israel when his Mapai (Labour) party won the largest number of seats in the first national election, held on 14 February 1949. He would remain in that post until 1963, except for a period of nearly two years between 1954 and 1955. As Prime Minister, he oversaw the establishment of the state's institutions. He presided over various national projects aimed at the rapid development of the country and its population: Operation Magic Carpet, the airlift of Jews from Arab countries, the construction of the National Water Carrier, rural development projects and the establishment of new towns and cities. In particular, he called for pioneering settlement in outlying areas, especially in the Negev. Ben Gurion saw the struggle to make the Negev desert bloom as an area where the Jewish people could make a major contribution to humanity as a whole.

During this period, Palestinian fedayeen repeatedly infiltrated into Israel from Arab territory and attacked Israelis. Initially, small scale infiltrations were mounted by refugees, often for economic reasons, but they were quickly adopted by the militaries of the neighboring Arab states, which organized them into semi - formal brigades. From 1954 onwards, the fedayeen began carrying out larger scale guerilla actions. Thousands of attacks were launched, causing hundreds of Israeli casualties. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) could not effectively respond to these infiltrations. In 1953, after a handful of unsuccessful retaliatory actions, Ben Gurion charged Ariel Sharon, then security chief of the northern region, with setting up a new commando unit designed to respond to fedayeen infiltrations. Ben Gurion told Sharon that "the Palestinians must learn that they will pay a high price for Israeli lives." Sharon formed Unit 101, a small commando unit answerable directly to the IDF General Staff tasked with retaliating for fedayeen raids. During its five months of existence, the unit launched repeated raids against military targets and villages used as bases by the fedayeen. These attacks became known as the Retribution operations.

In his "retribution operations as a means to ensure the peace" speech, Ben Gurion described his intentions: "We do not have the power to ensure that the water pipe lines won't be exploded or that the trees won't be uprooted. We do not have the power to prevent the murders of orchard workers or families while they are asleep, but we have the power to set a high price for our blood, a price which would be too high for the Arab communities, the Arab armies and the Arab governments to bear".

In October 1953, a raid by Unit 101 in the West Bank village of Qibya resulted in the deaths of 69 Arab civilians. The event became known as the Qibya massacre. The raid was universally condemned by the international community. Unit 101 was subsequently disbanded and merged into the Paratroopers Brigade. IDF units, especially the Paratroopers Brigade, continued to carry out retaliatory actions against Arab targets.

In 1953, Ben Gurion announced his intention to withdraw from government and was replaced by Moshe Sharett, who was elected the second Prime Minister of Israel in January 1954. However, Ben Gurion temporarily served as acting prime minister when Sharett visited the United States in 1955. During Ben Gurion's tenure as acting prime minister, the IDF carried out Operation Olive Leaves, a successful attack on fortified Syrian emplacements near the northeastern shores of the Sea of Galilee. The operation was a response to Syrian attacks on Israeli fishermen. Ben Gurion had ordered the operation without consulting the Israeli cabinet and seeking a vote on the matter, and Sharett would later bitterly complain that Ben Gurion had exceeded his authority.

Ben Gurion returned to government in 1955. He assumed the post of Defense Minister and was soon re-elected prime minister. When Ben-Gurion returned to government, Israeli forces began responding more aggressively to Egyptian sponsored Palestinian guerilla attacks from Gaza — still under Egyptian rule. The growing cycle of violence led Egypt's President Gamal Abdel Nasser to build up his arms with the help of the Soviet Union. The Israelis responded by arming themselves with help from France. Nasser blocked the passage of Israeli ships through the Red Sea and Suez Canal. In July 1956, the United States and Britain withdrew their offer to fund the Aswan High Dam project on the Nile and a week later, Nasser ordered the nationalization of the French and British controlled Suez Canal. Ben Gurion collaborated with the British and French to plan the 1956 Sinai War in which Israel invaded and occupied Gaza and the Sinai Peninsula, thus giving British and French forces a pretext to militarily intervene against Egypt in order to secure the Suez Canal. Intervention by the United States and the United Nations forced the British and French to back down and Israel to withdraw from Sinai in return for promises of free navigation through the Red Sea and Suez Canal. A UN force was stationed between Egypt and Israel.

Ben Gurion stepped down as prime minister for what he described as

personal reasons in 1963, and chose Levi Eshkol as his successor. A year

later a rivalry developed between the two on the issue of the Lavon

Affair,

an Israeli covert operation in Egypt. Ben Gurion broke with the party

in June 1965 over Eshkol's handling of the Lavon Affair and formed a new

party, Rafi which won ten seats in the Knesset.

In May 1967, Egypt began deploying forces in the Sinai after expelling UN peacekeepers and closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping. This, together with the actions of other Arab states, caused Israel to begin preparing for war. The situation lasted until the outbreak Six - Day War broke out on June 5. In Jerusalem, there were calls for a unity government or an emergency government. During this period, Ben Gurion met with his old rival Menachem Begin in Sde Boker. Begin asked Ben Gurion to join Eshkol's unity government. Although Eshkol's Mapai party initially opposed the widening of its government, it eventually changed its mind. On May 23, IDF Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin met with Ben Gurion to ask for reassurance. Ben Gurion, however, accused Rabin of putting Israel in mortal danger by mobilizing the reserves and openly preparing for war with an Arab coalition. Ben Gurion told Rabin that at the very least, he should have obtained the support of a foreign power, as he had done during the Suez Crisis. Rabin was shaken by the meeting and took to bed for 36 hours.

On June 5, the Six - Day War began with preemptive Israeli air that decimated the Egyptian, Syrian, and Jordanian air forces. Israel then captured the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip from Egypt, the West Bank and East Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria in a series of ground offensives. Following the war, Ben Gurion was in favor of returning all the captured territories apart from East Jerusalem, the Golan Heights and Mount Hebron as part of a peace agreement.

On June 11, Ben Gurion met with a small group of supporters in his home. During the meeting, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan proposed autonomy for the West Bank, the transfer of Gazan refugees to Jordan, and a united Jerusalem serving as Israel's capital. Ben Gurion agreed with him, but foresaw problems in transferring Palestinian refugees from Gaza to Jordan, and recommended that Israel insist on direct talks with Egypt, favoring withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula in exchange for peace and free navigation through the Straits of Tiran. The following day, he met with Jerusalem mayor Teddy Kollek in his Knesset office. Despite occupying a lower executive position, Ben Gurion treated Kollek like a subordinate.

On June 13, Ben Gurion asked and was granted permission by General Chaim Herzog, East Jerusalem's military governor, to visit the Old City, Bethlehem and Hebron. While on his way to the Western Wall, he noticed Arab residents who had been ordered to face the wall while the vehicle passed, and was told that this precaution was taken after Arabs had attacked passers by, apparently Jews on their way to pray at the wall. Ben Gurion called it "a disgraceful sight", and claimed that to "shame and humiliate" people in that way "degrades us as well". In front of the wall, he noticed a tile sign reading "Al-Burak Road" in English and Arabic, and had it pried off. As the surrounding crowd cheered, Ben Gurion exclaimed, "this is the greatest moment of my life since I came to Israel." However, Ben Gurion was furious when he saw candles being lit, feeling that this custom marred the wall and should be prohibited. Ben Gurion also visited the Mount Scopus campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron. On the way back, he visited the site of the Etzion bloc. Returning to Jerusalem, he met again with Kollek. Ben Gurion suggested to Kollek that Arab homes in the Jewish Quarter be rebuilt and repopulated with Jews, Arabs evicted during the process be resettled in West Jerusalem, and that any vacant homes in the city be given to Jews.

Following the Six - Day War, Ben Gurion repeatedly brought up the issue of government activity in Jerusalem, and harshly criticized what he saw as the government's apathy towards the construction and development of the city. To ensure that a united Jerusalem remained in Israeli hands, he advocated a massive Jewish settlement program for the Old City and the hills surrounding the city, as well as the establishment of large industries in the Jerusalem area to attract Jewish migrants. He argued that no Arabs would have to be evicted in the process. Ben Gurion also urged extensive Jewish settlement in Hebron.

In 1968, when Rafi merged with Mapai to form the Alignment,

Ben Gurion refused to reconcile with his old party. He favored

electoral reforms in which a constituency based system would replace

what he saw as a chaotic proportional representation method. He formed

another new party, the National List, which won four seats in the 1969 election.

Ben Gurion retired from politics in 1970 and spent his last years living in a modest home on the kibbutz, though in 1971, he visited Israeli positions along the Suez Canal during the War of Attrition.

Ben Gurion died of a brain hemorrhage on 1 December 1973, shortly after the end of the Yom Kippur War.

His body lay in state in the Knesset compound before being flown by

helicopter to Sde Boker. Sirens sounded across the entire country to

mark his death. He was buried in a simple funeral alongside his wife

Paula at Midreshet Ben Gurion.

- In both 1951 and 1971, Ben Gurion was awarded the Bialik Prize for Jewish thought.

In 2005, he was voted the 2nd greatest Israeli of all time, in a poll by the Israeli news website Ynet to determine whom the general public considered the 200 Greatest Israelis.

Abdul Rahman Hassan Azzam (Arabic: عبد الرحمن حسن عزام) (1893 – 1976), also known as Azzam Pasha, was an Egyptian diplomat, with family origins in Egypt. He served as the first secretary general of the Arab League between 1945 and 1952.

Azzam also had a long career as an ambassador and parliamentarian.

He was an Egyptian nationalist and one of the foremost proponents of

pan - Arab idealism – viewpoints he did not see as contradictory - and was

passionately opposed to the partition of Palestine.

Abd al-Rahman Azzam's father, Hassan Bey, was born into an Arab family that rose to prominence in the first half of the nineteenth century in Shubak al-Gharbi, a village near the city of Helwan, located south of Cairo. His grandfather, Salim Ali Azzam, was one of the first Arabs to become director of southern Giza, and his father, Hassan Salim Azzam, was likewise active in many governing bodies of the region. Azzam's mother, Nabiha, was descended from no less distinguished a family. Her father, Khalaf al-Saudi, was a land proprietor as well as a shaykh while her mother's family descended from various tribes of the Arabian Peninsula.

As biographer Ralph Coury notes, scholars and others have often

concluded that Azzam's "Peninsular" origins explain his later assumption

of an Arab identity. As early as 1923, one British official wrote that

"The Azzam family, though settled in Egypt for some generations, come of

good old Arab stock, and have always clung tenaciously to Arab

traditions and ideals of life," adding that "in estimating Abdul

Rahman's character, his early up-bringing and his Arab blood must never

be forgotten." However, as Coury has shown, the Azzams were in fact completely

assimilated to village life and did not see themselves as set apart from

other Egyptians. Azzam himself even once asserted that "we were not

brought up with a strong consciousness of Bedouin descent. We were Arabs because we were 'sons' or 'children' of the

Arabs' in contrast to the Turks, but the term 'Arab' as such was used

for the Bedouin and we would not apply it to one another."

Abd al-Rahman Azzam, the eighth of twelve children, was born on March 8, 1893 in Shubak al-Gharbi. His family were fellahin dhwati ("notable peasants") whose position was determined by the possession of land, wealth, and political power. The Azzam household was frequently home to gatherings of the village elite and was where Azzam developed his interest in politics at an early age. According to his brother, Abd al-Aziz Azzam, Azzam was a "born politician" who often would stand at the top of the stairs as a child and give political speeches to his siblings.

In 1903, the Azzam family moved to Helwan in order to eliminate Hassan Bey's traveling to and from the city for government meetings. The various effendis that had been frequent visitors to Shubak were now neighbors of the Azzams, and the friendship that quickly developed between the effendi children and Azzam led him to insist on attending secular primary school (ibtidaiyyah) instead of studying at the Azhar. Azzam remained in Helwan through secondary school and upon graduating decided to next study medicine. Of his decision, Azzam explained, "I wanted to be active in politics and I thought that I could practice medicine wherever that struggle might lead." In 1912, Azzam left Egypt for London where he enrolled in St. Thomas’s Hospital Medical School.

While in London, Azzam joined the Sphinx Society, a political grouping where Azzam quickly grew to prominence. However, after his first year of study, Azzam became increasingly concerned with the recent developments in the Balkans and felt compelled to contribute in some way to the Ottoman cause. Unsure of how he could personally contribute, Azzam decided to leave London and head for the Balkans, spending considerable time in Istanbul, Albania and Anatolia. Throughout his travels, Azzam made various connections with like - minded political activists. He also had the opportunity to meet and talk with many non-Egyptian Arabs.

Once back in Egypt, Azzam was banned by the occupation authorities

from returning to England because of his nationalist activities in both

England and Egypt. Instead, arrangements were made for Azzam to attend the Cairo Medical School of Qasr al-Ayni. While studying in Cairo, Azzam became greatly disaffected by the British Occupation which revived his desire to leave the country and join the Ottomans.

Azzam actively participated in the Libyan resistance against the Italians from 1915 - 1923. In December 1915, Azzam left Egypt to join Nuri Bery and a group of Ottoman officers who were leading a Sanusi army in fighting against the British. After the fighting ceased and Sayyid Idris and the British signed a peace treaty in 1917, Nuri Bey and Azzam transferred to Tripolitania where they hoped to build up a centralized authority. On November 18, 1918, leaders met at al-Qasabat and proclaimed the founding of a Tripolitanian Republic. Following numerous negotiations between the Italians and Tripolitanian chiefs, on June 1, 1919, the Fundamental Law of Tripolitania was enacted, granting the natives full Italian nationality with all civil and political rights pertaining to it. Despite the agreement, the Italians refused to implement the law which consequently led to the formation of a National Reform Party. Led by Azzam, this group was formed in order to pressure the Italians to put the law into effect. The Italians refused to concede, and in January 1923, Azzam accompanied Sayyid Idris into exile in Egypt. By 1924, opposition in Tripolitania had sufficiently waned and the Italians remained militarily victorious.

Azzam's tenure spent participating in the Libyan Resistance is

credited for his turn to Arabism. In 1970, Azzam noted: "When I was a

boy, I was an Egyptian Muslim. Being an Egyptian and Muslim didn't

change. But from 1919 on, with Syria and Iraq gone, I started talking of

Arabism. Living with the bedouin, etc. worked gradually to make me a

supporter for something Arabic. The Tripolitanian Republic decisively

marked the shift to Arabism."

Azzam's return to Egypt coincided with the numerous debates taking place between the Wafd, the Palace, and the British regarding the new constitution. Hoping to reestablish himself in Egypt, Azzam ran for office in 1924 and was elected to parliament as a member of the Wafd. As a parliamentarian, Azzam rose to prominence through his articulate writings for the party's newspaper.

Due to his time spent in Libya, the Wafd often chose Azzam to represent the party at official meetings and international conferences. His most important trip made as an Egyptian - Wafd representative was to the General Islamic Conference in Jerusalem in 1931. Because members of the Azhar and Sidqi ministry were strongly opposed to two of the conference's main agenda items - the idea of creating a new Islamic University in Jerusalem and restoration of the Caliphate - the Egyptian government refused to send an official delegate to the meeting. Still, Azzam and several other members of the Egyptian opposition attended the conference. Azzam took an active role in the proceedings and was elected to the Executive Committee of the Congress which discussed the question of Arab nationalism at length. This conference is one of the first instances in which Arab nationalists included Egypt as part of the Arab nation.

In November 1932, Azzam made a decisive break along with several other party members from the Wafd. While some viewed him as a traitor, Azzam maintained that changes in his own opinions were to blame. By this point, Azzam's reputation for knowledge of Arab affairs was highly valued and he soon became a member of the Palace entourage that gathered around King Faruq.

After breaking with the Wafd, Azzam joined the elite ranks of liberals -

all Wafd and Liberal Constitutionalist dissidents - who had supported

Liberal proposals for a coalition government in 1932. In 1936, 'Ali

Mahir appointed Azzam as Egyptian Minister to Iraq and Iran, and in

1937, the Nahhas ministry increased Azzam's diplomatic role to include

that of Egyptian Minister of Saudi Arabia.

In 1945, Azzam was selected to be the first Secretary General of the Arab League. One of Azzam's first acts as secretary general was to condemn anti - Jewish rioting in Egypt of November 2–3, 1945 during which Jewish and other non-Muslim owned shops were destroyed and the Ashkenazi synagogue in Cairo's Muski quarter was set aflame.

On March 2, 1946, in an address to The Anglo - American Committee of Inquiry into the Problems of European Jewry and Palestine, Azzam explained the Arab League’s attitude towards the Palestine question and rejected the Zionist claim to Palestine:

- Our brother has gone to Europe and to the West and come back something else. He has come back with a totally different conception of things, West and not Eastern. That doesn’t mean that we are necessarily quarreling with anyone who comes from the West. But the Jew, our old cousin, coming back with imperialistic ideas, with materialistic ideas, with reactionary or revolutionary ideas and trying to implement them first by British pressure and then by American pressure, and then by terrorism on his own part – he is not the old cousin and we do not extend to him a very good welcome. The Zionist, the new Jew, wants to dominate and he pretends that he has got a particular civilizing mission with which he returns to a backward, degenerate race in order to put the elements of progress into an area which wants no progress. Well, that has been the pretension of every power that wanted to colonize and aimed at domination. The excuse has always been that the people are backward and that he has got a human mission to put them forward. The Arabs simply stand and say NO. We are not reactionary and we are not backward. Even if we are ignorant, the difference between ignorance and knowledge is ten years in school. We are a living, vitally strong nation, we are in our renaissance; we are producing as many children as any nation in the world. We still have our brains. We have a heritage of civilization and of spiritual life. We are not going to allow ourselves to be controlled either by great nations or small nations or dispersed nations. (Richard H.S. Crossman, Palestine Mission: A Personal Record, 1947)"

On May 11, 1948 Azzam warned the Egyptian government that owing to

public pressure and strategic issues it would be difficult for Arab

leaders to avoid intervention in the Palestine War, and that Egypt could

find itself isolated if it did not act in concert with its neighbors.

Azzam believed that King Abdullah of Jordan

had decided to move his forces into Palestine on 15 May regardless of

what the other Arabs did and would occupy the Arab part of Palestine

whilst blaming other Arab states for failure. King Farouk of Egypt

resolved to contain Abdullah and prevent him from gaining further

influence and power in the Arab arena. Six days after the Arab intervention

in the conflict began, Azzam told reporters "We are fighting for an

Arab Palestine. Whatever the outcome the Arabs will stick to their offer

of equal citizenship for Jews in Arab Palestine and let them be as

Jewish as they like. In areas where they predominate they will have

complete autonomy."

One day after the State of Israel declared itself as an independent nation (May 14, 1948), Lebanese, Syrian, Iraqi, Egyptian, and Transjordanian troops, supported by Saudi and Yemenite troops, attacked the nascent Jewish state, triggering the 1948 Arab - Israeli War. A regularly cited claim is that Azzam declared on that day or on the eve of the war:

| “ | "This will be a war of extermination and a momentous massacre which will be spoken of like the Mongolian massacres and the Crusades." | ” |

The source of the quotation is usually given as a press conference in Cairo, which some versions say was broadcast by the BBC. An Egyptian writer in 1961 maintained that the quotation was "completely out of context". He wrote that "Azzam actually said that he feared that if the people of Palestine were to be forcibly and against all right dispossessed, a tragedy comparable to the Mongol invasions and the Crusades might not be avoidable. ..... The reference to the Crusaders and the Mongols aptly describes the view of the foreign Zionist invaders shared by most Arabs."

In 2010, doubt over the provenance of the quotation was voiced by Joffe and Romirowsky and by Morris.

The truth about the quotation was reported on Wikipedia late in 2010 and was later the subject of an article published by David Barnett and Efraim Karsh. Azzam's words were found to have come from a time several months earlier, in a October 11, 1947 interview in the Egyptian newspaper Akhbar el-Yom.

In that interview he is reported as saying:

| “ | "Personally I hope the Jews do not force us into this war because it will be a war of elimination and it will be a dangerous massacre which history will record similarly to the Mongol massacre or the wars of the Crusades. I think the number of volunteers from outside Palestine will exceed the Palestinian population." | ” |

At the time Azzam gave the interview, the United Nations UNSCOP commission had presented its report recommending that Palestine be partitioned into an Arab State, a Jewish State, and a special regime for Jerusalem. However, no decision had yet been made by the UN, and no Arab state had yet decided to intervene in Palestine with its regular armed forces. After the partition resolution had been passed, the comparison of the Zionists to the Mongols and the Crusaders was repeated when Azzam told a rally of students in Cairo in early December of that year that, "The Arabs conquered the Tartars and the Crusaders and they are now ready to defeat the new enemy," echoing sentiments he had expressed to a journalist the previous day.

The Akhbar el-Yom quotation, without its initial caveat, appeared in English in a Jewish Agency memorandum in February 1948. During the next few years, the same partial sentence appeared in its correct 1947 setting in several books. However, by 1952, many publications, including one published by the Israeli government, had moved its date to 1948. In this incorrect setting, it has appeared in hundreds of books and thousands of websites.

According to historians Israel Gershoni and James Jankowski, Azzam

denied that the Egyptian nation was a continuation of Pharaonic Egypt.

Instead he believed that "modern Egypt had been shaped primarily by

'Arab religion, customs, language, and culture.'" Accordingly, he asserted a racial basis for Egyptian identification with the Arabs.

Vincent Sheean points out in his introduction to the book The Eternal Message of Muhammad, (published by Azzam in Arabic in 1938 under the title The Hero of Heroes or the most Prominent Attribute of the Prophet Muhammad), "In Damascus as well as in Djakarta, Istanbul and Baghdad, this man is known for valor of spirit and elevation of mind... he combines in the best Islamic mode, the aspects of thought and action, like the Muslim warriors of another time who are typified for us Westerners by the figure of Saladin." In the book Azzam extols the Prophet’s virtues of bravery, love, the ability to forgive, and eloquence in pursuit of the diplomatic resolution of conflict and argues that Islam is incompatible with racism or fanatical attachment to "tribe, nation, color, language, or culture".

Malcolm X’s reading of The Eternal Message of Muhammad and his meeting with Azzam Pasha are vividly recounted in his autobiography. These events marked the point in his life at which Malcolm X turned towards orthodox traditional Islam.