<Back to Index>

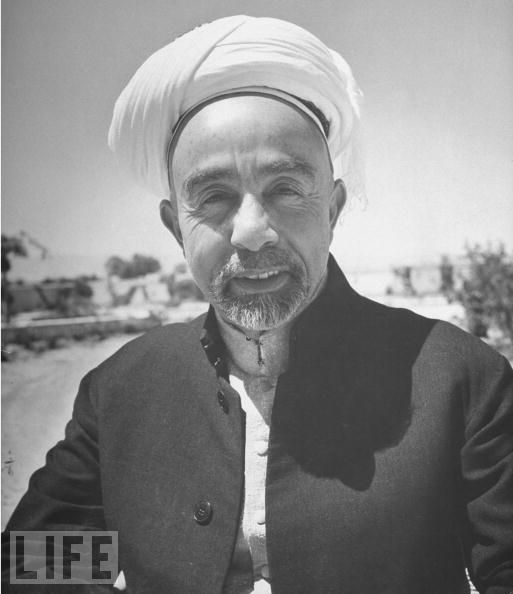

- King of Jordan Abdullah I bin al-Hussein, 1882

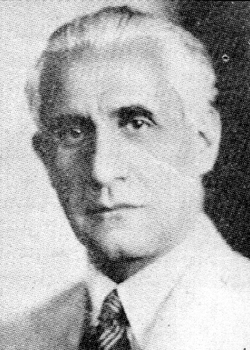

- Prime Minister of Iraq Muzahim al-Pachachi, 1890

- Dictator of Syria Husni al-Za'im, 1897

PAGE SPONSOR

Abdullah I bin al-Hussein, King of Jordan (February 1882 – 20 July 1951) (Arabic) عبد الله الأول بن الحسين born in Mecca, Second Saudi State, (in modern day Saudi Arabia) was the second of three sons of Sherif Hussein bin Ali, Sharif and Emir of Mecca and his first wife Abdiyya bint Abdullah (d. 1886). He was educated in Istanbul (Constantinople), Turkey and Hijaz. From 1909 to 1914, Abdullah sat in the Ottoman legislature, as deputy for Mecca, but allied with Britain during World War I. Between 1916 to 1918, working with the British guerrilla leader T.E. Lawrence, he played a key role as architect and planner of the Great Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule, leading guerrilla raids on garrisons. He was the ruler of Transjordan and its successor state, Jordan, from 1921 to 1951 — first as Emir under a British Mandate from 1921 to 1946, then as King of an independent nation from 1946 until his assassination.

In 1910 Abdullah persuaded his father to stand, successfully, for Grand Sharif of Mecca, a post for which Hussein acquired British support. In the following year he became deputy for Mecca in the parliament established by the Young Turks, acting as an intermediary between his father and the Ottoman government. In 1914, Abdullah paid a secret visit to Cairo to meet Lord Kitchener in a bid to drum up British support for his father's ambitions in Arabia.

Abdullah maintained contact with the British throughout the First

World War and in 1915 encouraged his father to enter into correspondence

with Sir Henry McMahon, British high commissioner in Egypt, about Arab

independence from Turkish rule. (McMahon - Hussein Correspondence). During the Arab Revolt of 1916 – 18, Abdullah commanded the Arab Eastern Army.

Abdullah began his role in the Revolt by attacking the Ottoman garrison

at Ta’if on June 10, 1916. The garrison consisted of 3,000 men with ten

75-mm Krupp

guns. Abdullah led a force of 5,000 tribesmen but they did not have the

weapons or discipline for a full attack. Instead he laid siege to the

town.

In July he received reinforcements from Egypt in the form of howitzer

batteries manned by Egyptian personnel. On 16 July his artillery began

shelling the defenders but it was not until September 22, 1916, that the

garrison surrendered. He then joined the siege of Medina commanding a

force of 4,000 men based to the east and north - east of the town. In

early 1917, Abdullah ambushed an Ottoman convoy in the desert, and

captured £20,000 worth of gold coins that were intended to bribe the

Bedouin into loyalty to the Sultan. In August 1917, Abdullah worked

closely with the French Captain Muhammand Ould Ali Raho in sabotaging

the Hejaz Railway. Abdullah's relations with the British Captain T.E.

Lawrence were not good, and as a result, Lawrence spent most of his time

in the Hejaz serving with Abdullah's brother Faisal who commanded the

Arab Northern Army.

When French forces captured Damascus at the Battle of Maysalun and expelled his brother Faisal, Abdullah moved his forces from Hejaz into Transjordan with a view to liberating Damascus, where his brother had been proclaimed King in 1918. Having heard of Abdullah's plans, Winston Churchill invited Abdullah to a famous "tea party" where he convinced Abdullah to stay put and not attack Britain's allies, the French. Churchill told Abdullah that French forces were superior to his and that the British did not want any trouble with the French. Abdullah acquiesced and was rewarded when the British created a protectorate for him, which later became a state; Transjordan. He embarked on negotiations with the British to gain independence, resulting in the announcement of the Emirate of Transjordan’s independence on 25 May 1946 as the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan (renamed simply Jordan in 1949). This date is Jordan’s official independence day. His brother Faisal became King of Iraq.

Abdullah set about the task of building Transjordan with the help of a reserve force headed by Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Peake, who was seconded from the Palestine police in 1921. The force, renamed the Arab Legion, in 1923 was led by Glubb Pasha (Sir John Bagot Glubb) between 1930 and 1956.

Although Abdullah established a legislative council in 1928 its role remained advisory leaving him to rule as an autocrat.

During the Second World War Abdullah was a faithful ally of the British, maintaining strict order within Transjordan, and helping to suppress a pro - Axis uprising in Iraq.

Prime Ministers under Abdullah formed 18 governments during the 23 years of the Emirate.

Abdullah, alone among the Arab leaders of his generation, was considered a moderate by the West. It is possible that he might have been willing to sign a separate peace agreement with Israel, but for the Arab League's militant opposition. Because of his dream for a Greater Syria comprising the borders of what was then Transjordan, Syria, Lebanon and the British Mandate for Palestine under a Hashemite dynasty with "a throne in Damascus," many Arab countries distrusted Abdullah and saw him as both "a threat to the independence of their countries and they also suspected him of being in cahoots with the enemy" and in return, Abdullah distrusted the leaders of other Arab countries.

Abdullah supported the Peel Commission in 1937, which proposed that Palestine be split up into a small Jewish state (20 percent of the British Mandate for Palestine) and the remaining land be annexed into Transjordan. The Arabs within Palestine and the surrounding Arab countries objected to the Peel Commission while the Jews accepted it reluctantly. Ultimately, the Peel Commission was not adopted.

In 1946 – 1948, Abdullah actually supported partition in order that the Arab allocated areas of the British Mandate for Palestine could be annexed into Transjordan. Abdullah went so far as to have secret meetings with the Jewish Agency (future Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir was among the delegates to these meetings) that came to a mutually agreed upon partition plan independently of the United Nations in November 1947. On November 17, 1948 in a secret meeting with Meir, Abdullah stated that he wished to annex all of the Arab parts as a minimum, and would prefer to annex all of Palestine. This idea of secret Zionist - Hashemite negotiations in 1947 was expanded upon by New Historian Avi Shlaim in his book Collusion Across The Jordan: King Abdullah, the Zionist Movement, and the Partition of Palestine. This partition plan was supported by British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin who preferred to see Abdullah's territory increased at the expense of the Palestinians rather than risk the creation of a Palestinian state headed by the Mufti of Jerusalem Mohammad Amin al-Husayni.

The claim has, however, been strongly disputed by Israeli historian Efraim Karsh. In an article in Middle East Quarterly,

he alleged that "extensive quotations from the reports of all three

Jewish participants [at the meetings] do not support Shlaim's

account... the report of Ezra Danin and Eliahu Sasson

on the Golda Meir meeting (the most important Israeli participant and

the person who allegedly clinched the deal with Abdullah) is

conspicuously missing from Shlaim's book, despite his awareness of its

existence".

According to Karsh, the meetings in question concerned "an agreement

based on the imminent U.N. Partition Resolution, [in Meir's words] "to

maintain law and order until the UN could establish a government in that

area"; namely, a short lived law enforcement operation to implement the

UN Partition Resolution, not obstruct it".

On May 4, 1948 Abdullah, as a part of the effort to seize as much of Palestine as possible, sent in the Arab Legion to attack the Israeli settlements in the Etzion Bloc. Less than a week before the outbreak of the 1948 Arab - Israeli War, Abdullah met with Meir for one last time on May 11, 1948. Abdullah told Meir, "Why are you in such a hurry to proclaim your state? Why don't you wait a few years? I will take over the whole country and you will be represented in my parliament. I will treat you very well and there will be no war". Abdullah proposed to Meir the creation "of an autonomous Jewish canton within a Hashemite kingdom," but "Meir countered back that in November, they had agreed on a partition with Jewish statehood." Depressed by the unavoidable war that would come between Jordan and the Yishuv, one Jewish Agency representative wrote, "[Abdullah] will not remain faithful to the 29 November [UN Partition] borders, but [he] will not attempt to conquer all of our state [either]." Abdullah too found the coming war to be unfortunate, in part because he "preferred a Jewish state [as Transjordan's neighbor] to a Palestinian Arab state run by the mufti."

The Palestinian Arabs, the neighboring Arab states, the promise of the expansion of territory and the goal to conquer Jerusalem finally pressured Abdullah into joining them in an "all - Arab military intervention" against the newly created State of Israel on 15 May 1948, which he used to restore his prestige in the Arab world, which had grown suspicious of his relatively good relationship with Western and Jewish leaders. Abdullah was especially anxious to take Jerusalem as compensation for the loss of the guardianship of Mecca, which had traditionally held by the Hashemites until Ibn Saud had seized the Hejaz in 1925. Abdullah's role in this war became substantial. He distrusted the leaders of the other Arab nations and thought they had weak military forces; the other Arabs distrusted Abdullah in return. He saw himself as the "supreme commander of the Arab forces" and "persuaded the Arab League to appoint him" to this position. His forces under their British commander Glubb Pasha did not approach the area set aside for the new Israel, though they clashed with the Yishuv forces around Jerusalem, intended to be an international zone. According to Abdullah el Tell it was the King's personal intervention that led to the Arab Legion entering the Old City against Glubb's wishes.

After conquering the West Bank and East Jerusalem

at the end of the war, King Abdullah tried to suppress any trace of a

Palestinian Arab national identity. Abdullah annexed the conquered

Palestinian territory and granted the Palestinian Arab residents in

Jordan Jordanian citizenship. In 1949, Abdullah entered secret peace

talks with Israel, including at least five with Moshe Dayan, the

Military Governor of West Jerusalem and other senior Israelis.

News of the negotiations provoked a strong reaction from other Arab

States and Abdullah agreed to discontinue the meetings in return for

Arab acceptance of the West Bank's annexation into Jordan.

On 20 July 1951, Abdullah, while visiting Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, was shot dead by "a Palestinian from the Husseini clan." On 16 July, Riad Bey al-Solh, a former Prime Minister of Lebanon, had been assassinated in Amman, where rumors were circulating that Lebanon and Jordan were discussing a joint separate peace with Israel. The assassin passed through apparently heavy security. Abdullah was in Jerusalem to give a eulogy at the funeral and for a prearranged meeting with Reuven Shiloah and Moshe Sasson. Abdullah was shot while attending Friday prayers at the Dome of the Rock in the company of his grandson, Prince Hussein. The Palestinian gunman, motivated by fears that the old king would make a separate peace with Israel, fired three fatal bullets into the King's head and chest. Abdullah's grandson, Prince Hussein, was at his side and was hit too. A medal that had been pinned to Hussein's chest at his grandfather's insistence deflected the bullet and saved his life. Once Hussein became king, the assassination of Abdullah was said to have influenced Hussein not to enter peace talks with Israel in the aftermath of the Six - Day War in order to avoid a similar fate.

The assassin was a 21 year old tailor's apprentice, Mustafa Ashu, who according to Alec Kirkbride, the British Resident in Amman, was a "former terrorist", Zakariya Okkeh, a livestock dealer and butcher. Ten conspirators were accused of plotting the assassination and were brought to trial in Amman. The prosecution named Colonel Abdullah el Tell, ex-Military Governor of Jerusalem, and Dr. Musa Abdullah Husseini as the chief plotters of "the most dastardly crime Jordan ever witnessed." The Jordanian prosecutor asserted that Col. Tell, who had been living in Cairo since January 1950, had given instructions that the killer, made to act alone, be slain at once thereafter to shield the instigators of the crime. Jerusalem sources added that Col. Tell had been in close contact with the former Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Amin al-Husayni, and his adherents in Arab Palestine. Tell and Dr. Husseini, and three co-conspirators from Jerusalem were sentenced to death. On 6 September 1951 Dr. Musa Ali Husseini, 'Abid and Zakariyya Ukah, and Abd-el-Qadir Farhat were executed by hanging.

Abdullah was succeeded by his son Talal; however, since Talal was

mentally ill, Talal's son Prince Hussein became the effective ruler as King Hussein at the age of seventeen. In 1967 Abdullah el Tell received a full pardon from King Hussein.

Muzahim al-Pachachi (September 22, 1891 – September 23, 1982), Iraqi politician and diplomat was the Prime Minister of Iraq at the time of 1948 Arab - Israeli war.

Born to a prominent family and graduated from the Baghdad School of Law he organized the Arab nationalist Cultural Club in Baghdad in 1912; its members included Hamdi al-Pachachi, Talib al-Naqib and Muhammad Ridha. In 1924, al-Pachachi was elected a member of the Constituent Assembly, charged with drafting the Constitution of Iraq. He held a number of cabinet and diplomatic positions. He served as Minister of Works (1924 - 25) before becoming a member of parliament (1925 - 27). He was appointed ambassador to Britain (1927 - 28) and was briefly Minister of the Interior (1930).

Al-Pachachi opposed the 1930 Anglo - Iraqi Treaty because it failed to meet nationalist demands. He held a succession of ambassadorial posts: ambassador to the League of Nations (1933 - 35), to Italy (1935 - 39), and to France (1939 - 42). During the occupation of France in World War II, al-Pachachi stayed in Switzerland. He became active in the 1930s and 1940s in pro-Palestinian activities and opposed the 1948 United Nations truce in Palestine. The prime ministers of Iraq in 1948 were Sayyid Muhammad as-Sadr (January - June) and Muzahim al-Pachachi (June 1948 - January 1949), both were distinguished personalities who were not part of the pro-British political circle and whose governments included ministers who identified with the anti - British elements. It was under the leadership of Pachachi that Iraq sent 15,000 to 18,000 troops to defend Palestine in the 1948 Arab - Israeli War, it was also during this time that Iraq led the Arab Liberation Army. However after the Arabs were defeated and Palestine was partitioned, his cabinet fell in January 1949. He was later appointed deputy Prime Minister (1949 - 50) and Minister of Foreign Affairs (1949 - 50). Al-Pachachi opposed the 1951 law that allowed Iraqi Jews to leave the country, although he himself left Iraq that year, returning after the 14 July Revolution in 1958. His son Adnan later served as a cabinet minister and diplomat.

Husni al-Za'im (May 11, 1897 – August 14, 1949) (Arabic: حسني الزعيم) was a Syrian military man and politician. Husni al-Za'im, whose family is of Kurdish ancestry, had been an officer in the Ottoman Army. After France instituted its colonial mandate over Syria after the First World War, he became an officer in the French Army. After Syria's independence he was made Chief of Staff, and led the Syrian Army into war with the Israeli Army in the 1948 Arab - Israeli War. The defeat of the Arab forces in that war shook Syria and undermined confidence in the country's chaotic parliamentary democracy.

On April 11, 1949, al-Za'im seized power in a bloodless coup d'état. The coup, according to declassified records and statements by former CIA agents, was sponsored by the United States CIA. Syria's President, Shukri al-Kuwatli, was briefly imprisoned, but then released into exile in Egypt. Al-Za'im also imprisoned many political leaders, such as Munir al-Ajlani, whom he accused of conspiring to overthrow the republic. The coup was carried out with discreet backing of the American embassy, and possibly assisted by the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, although al-Za'im himself is not known to have been a member. Among the officers that assisted al-Za'ims takeover was Adib al-Shishakli and Sami al-Hinnawi, both of whom would later become military leaders of the country.

Al-Za'im's takeover, the first military coup in the history of Syria, would have lasting effects, as it shattered the country's fragile and flawed democratic rule, and set off a series of increasingly violent military revolts. Two more would follow in 1949.

While his rule was relatively mild, with no executions of political opponents and few arrests of dissenters, al-Za'im quickly made enemies. His secular policies and proposals for the emancipation of women through granting them the vote and suggesting they should give up the Islamic practice of veiling, created a stir among Muslim religious leaders (Women's suffrage was only achieved during the third civilian administration of Hashim al-Atassi, a staunch opponent of military rule). Raising taxes also aggrieved businessmen, and Arab nationalists were still smouldering over his signing of a cease - fire with Israel, as well as his deals with US oil companies for building the Trans - Arabian Pipeline. He made a peace overture to Israel offering to settle 300,000 Palestinian refugees in Syria, in exchange for border modifications along the cease fire line and half of Israel's Lake Tiberias. Settling the refugees was made conditional on sufficient outside assistance for the Syrian economy. The overture was answered very slowly by Jerusalem and not treated seriously.

Lacking popular support, al-Za'im was overthrown after just four and a

half months by his colleagues, al-Shishakli and al-Hinnawi. As

al-Hinnawi took power as leader of a military junta, Husni al-Za'im was

swiftly spirited away to Mezze prison in Damascus, and executed along with Prime Minister Muhsin al-Barazi.

al-Za'im worked hard to abolish wearing the fez, claiming that it was outdated headwear taken from the days of the Ottoman Empire. He is credited for giving women the right to vote and run for public office in Syria. The law had been debated at the Syrian Parliament since 1920 and no leader dared push it through, except Zaim. Once, senior Muslim clerics demanded an audience with the president, objecting to the increasingly liberal lifestyle being promoted by Syrian women. One issue of particular concern was the mixing of men and women at the Grand Hotel in Bludan.

Zaim said yes, granting them an audience at the same hotel. When the

clerics walked in that evening, he had them seated around a dining

table, then snapped at one of the waiters, "Please prepare dinner, bring

the whiskey, and call in the dancing girls!" Zaim looked back at his

guests, who were horrified at his attitude, and no longer dared demand

enforcement of Islamic codes. During the 137 days of his rule in Syria,

however, Husni al-Zaim never executed anybody. He did have creative ways

of punishing those who disobeyed him, however. When the quality of

bread dropped to unacceptable levels, Zaim ordered all bakers to walk on

the gravel, barefoot, until blood flowed from their feet.

Husni al-Za’im's wife Nouran, was the first lady of Syria from April to August 1949. The marriage took place in 1947, two years before Husni al-Zaim became President of the Republic. In order to please his young wife, Zaim asked her 11 year old sister Kariman to live with them in Damascus. He treated her as a sister as well, and sent her to the Lycee Laique (one of the finest preparatory high schools in town). Another sister Orfan, would visit them often, and took up the habit of playing with a guard, Abdel Hamid Sarraj (the chief of security at the president's office who went on to become head of the intelligence bureau and minister of interior during the union years with Egypt 1958 - 1961).

During the incidence of al-Za'im's arrest, and when the guards came to arrest him, Zaim got dressed and said goodbye to his pregnant wife. "Relax" he asked her, "I will be back soon to receive our first baby together!" Niveen (his daughter) said, "My mother and aunt told me that the couch they had been sitting on was riddled with bullets. Sarraj knew in advance that an attack was coming and told them to go upstairs to keep them from harm's way." Less than a week before the coup — which led to the execution of Zaim and his Prime Minister Muhsen al-Barazi — Nouran's cousins came to him, saying that they had confirmed intelligence information, saying that Sami al-Hinnawi (his comrade from the war of 1948) was planning to have him killed. Zaim summoned Hinnawi and directly asked, "Sami, my brothers - in - law are telling me you want to kill me?" Hinnawi replied, "Impossible. How can I kill my leader and friend?" After the president was arrested on August 14, Nouran and her sister were kept under house arrest for an entire week. "No food was brought into the house" said Niveen. A Senegalese guard tried helping them by passing his own food through the window.