<Back to Index>

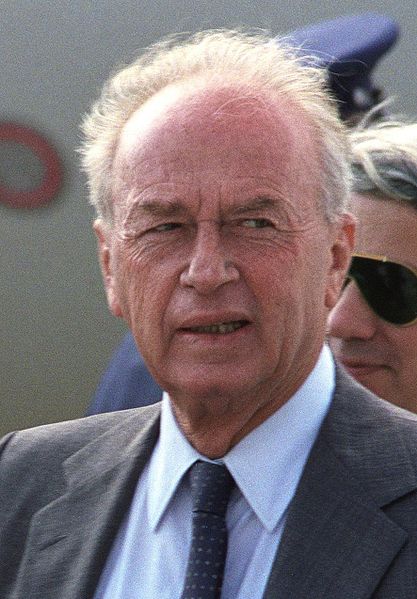

- Commander of the Harel Brigade Yitzhak Rabin, 1922

- Commander of the Arab Liberation Army Fawzi al-Qawuqji, 1890

PAGE SPONSOR

Yitzhak Rabin (help·info) (Hebrew: יִצְחָק רַבִּין; March 1, 1922 – November 4, 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the fifth Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974 – 77 and 1992 until his assassination in 1995.

In 1994, Rabin won the Nobel Peace Prize together with Shimon Peres

and Yasser Arafat. He was assassinated by right wing Israeli radical

Yigal Amir, who was opposed to Rabin's signing of the Oslo Accords.

Rabin was the first native born prime minister of Israel, the only prime

minister to be assassinated and the second to die in office after Levi

Eshkol.

Rabin was born in Jerusalem, British Mandate of Palestine, to Nehemiah and Rosa (née Cohen), two immigrants of the Third Aliyah, the third wave of Jewish immigration to Israel from Europe. Nehemiah Rubitzov was born in the Ukrainian village Sydorovychi near Ivankiv in 1886. His father died when he was a child, and he worked to support his family from a young age. At the age of 18, he emigrated to the United States, where he joined the Poale Zion party and changed his surname to Rabin. In 1917, Nehemiah went to the British Mandate of Palestine with a group of volunteers from the Jewish Legion.

Yitzhak's mother, Rosa Cohen, was born in 1890 in Mohilev in Belarus. Her father, a rabbi, opposed the Zionist movement and sent Rosa to a Christian high school for girls in Homel, enabling her to acquire a broad general education. Early on, Rosa took an interest in political and social causes. In 1919, she sailed to the region on the S.S. Ruslan, the bellwether of the Third Aliyah. After working on a kibbutz on the shores of the Sea of Galilee, she moved to Jerusalem.

Rabin grew up in Tel Aviv, where the family relocated when he was one year old. In 1940, he graduated with distinction from the Kadoori Agricultural High School and hoped to be an irrigation engineer. However, apart from several courses in military strategy in the United Kingdom later on, he never pursued a degree.

Rabin married Leah Rabin (born Schlossberg) during the 1948 Arab - Israeli War.

Leah Rabin was working at the time as a reporter for a Palmach

newspaper. They had two children, Dalia and Yuval. Rabin was non -

religious; according to American diplomat Dennis Ross, Rabin was the

most secular Jew he had met in Israel.

In 1941, during his practical training at kibbutz Ramat Yohanan, Rabin joined the Palmach section of the Haganah, under the influence of Yigal Allon. The first operation he participated in was assisting the allied invasion of Lebanon, then held by Vichy French forces (the same operation in which Moshe Dayan lost his eye) in June – July 1941.

After the end of the war the relationship between the Palmach and the British authorities

became strained, especially with respect to the treatment of Jewish

immigration. In October 1945 Rabin was in charge of planning and later

executing an operation for the liberation of interned immigrants from

the Atlit detainee camp for Jewish illegal immigrants. In the Black

Shabbat, a massive British operation against the leaders of the Jewish

Establishment in British Mandate Palestine,

Rabin was arrested and detained for five months. After his release he

became the commander of the second Palmach battalion and rose to the

position of Chief Operations Officer of the Palmach in October 1947.

During the 1948 Arab - Israeli War Rabin directed Israeli operations in Jerusalem and fought the Egyptian army in the Negev. During the beginning of the war he was the commander of the Harel Brigade, which fought on the road to Jerusalem from the coastal plain, including the Israeli "Burma Road", as well as many battles in Jerusalem, such as securing the southern side of the city by recapturing kibbutz Ramat Rachel.

During the First truce he participated in the altercation between the IDF and the Irgun on the beach of Tel Aviv as part of the Altalena Affair.

In the following period he was the deputy commander of Operation Danny, the largest scale operation to that point, which involved four IDF brigades. The cities of Ramle and Lydda were captured, as well as the major airport in Lydda, as part of the operation. Following the capture of the two towns there was an exodus of their Arab population, their expulsion order being signed by Rabin. Later, Rabin was Chief of Operations for the Southern Front and participated in the major battles ending the fighting there, including Operation Yoav and Operation Horev.

In the beginning of 1949 he was a member of the Israeli delegation to the armistice talks with Egypt that were held on the island of Rhodes. The result of the negotiations were the 1949 Armistice Agreements which ended the official hostilities of the 1948 Arab - Israeli War. Following the demobilization at the end of the war he was the most senior (former) member of the Palmach that remained in the IDF.

In 1964 he was appointed Chief of Staff of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) by Levi Eshkol who replaced David Ben Gurion and, like him, served as Prime Minister and Minister of Defense. Since Eshkol did not have much military experience, Rabin had a relatively free hand.

Under his command, the IDF achieved victory over Egypt, Syria and Jordan in the Six Day War in 1967. After the Old City of Jerusalem was captured by the IDF, Rabin was among the first to visit the Old City, and delivered a famous speech on Mount Scopus, at the Hebrew University. In the days leading up to the war, it was reported that Rabin suffered a nervous breakdown and was unable to function. After this short hiatus, he resumed full command over the IDF.

Following his retirement from the IDF he became ambassador to the United

States beginning in 1968, serving for five years. In this period the US

became the major weapon supplier of Israel and in particular he managed

to get the embargo on the F-4 Phantom fighter jets lifted. During the 1973 Yom Kippur war

he served in no official capacity and in the elections held at the end

of 1973 he was elected to the Knesset as a member of the Alignment. He

was appointed Israeli Minister of Labor in March 1974 in Golda Meir's

short lived government.

Following Golda Meir's resignation in April 1974, Rabin was elected party leader, after he defeated Shimon Peres. The rivalry between these two labor leaders remained fierce and they competed several times in the next two decades for the leadership role. Rabin succeeded Golda Meir as Prime Minister of Israel on 3 June 1974. This was a coalition government, including Ratz, the Independent Liberals, Progress and Development and the Arab List for Bedouins and Villagers. This arrangement, with a bare parliamentary majority, held for a few months and was one of the few periods in Israel's history where the religious parties were not part of the coalition. The National Religious Party joined the coalition on 30 October 1974 and Ratz left on 6 November.

In foreign policy, the major development at the beginning of Rabin's term was the Sinai Interim Agreement between Israel and Egypt, signed on 1 September 1975. Both countries declared that the conflict between them and in the Middle East shall not be resolved by military force but by peaceful means. This agreement followed Henry Kissinger's shuttle diplomacy and a threatened ‘reassessment’ of the United States’ regional policy and its relations with Israel. Rabin notes it was, ”an innocent sounding term that heralded one of the worst periods in American - Israeli relations.” The agreement was an important step towards the Camp David Accords of 1978 and the peace treaty with Egypt signed in 1979.

Operation Entebbe was perhaps the most dramatic event during Rabin's first term of office. On his orders, the IDF performed a long range undercover raid to rescue passengers of an airliner hijacked by militants belonging to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine's Wadie Haddad faction and the German Revolutionary Cells (RZ), and had been brought to Idi Amin's Uganda. The operation was generally considered a tremendous success, and its spectacular character has made it the subject of much continued comment and study.

Towards the end of 1976 his coalition government with the religious parties suffered a crisis: A motion of no confidence had been brought by Agudat Israel over a breach of the Sabbath on an Israeli Air Force base when four F-15 jets were delivered from the US and the National Religious Party had abstained. Rabin dissolved his government and decided on new elections, which were to be held in May 1977.

Following the March 1977 meeting between Rabin and U.S. President Jimmy Carter,

Rabin publicly announced that the U.S. supported the Israeli idea of

defensible borders; Carter then issued a clarification. A "fallout" in

U.S. / Israeli relations ensued. It is thought that the fallout

contributed to the Israeli Labor Party's defeat in the May 1977

elections. At the same time, it was revealed that his wife, Leah, continued to hold a US dollar account

from the days that Rabin was ambassador to the United States. According

to Israeli currency regulations at the time, it was illegal for

citizens to maintain foreign bank accounts without prior authorization.

In the wake of this disclosure, Rabin handed in his resignation from the

party leadership and candidacy for prime minister, an act that earned

him praise as a man of integrity.

Following his resignation and Labor Party defeat at the elections, Likud's Menachem Begin was elected in 1977. Until 1984 Rabin was a member of Knesset and sat on the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee. From 1984 to 1990, he served as Minister of Defense in several national unity governments led by prime ministers Yitzhak Shamir and Shimon Peres.

When Rabin came to office, Israeli troops were still deep in Lebanon. Rabin ordered their withdrawal to a "Security Zone" on the Lebanese side of the border. The South Lebanon Army was active in this zone, along with the Israeli Defense Forces.

When the first Intifada broke out, Rabin adopted harsh measures to stop the demonstrations, even authorizing the use of "Force, might and beatings," on the demonstrators. Rabin the "bone breaker" was used as an International image. The combination of the failure of the "Iron Fist" policy, Israel's deteriorating international image and Jordan cutting legal and administrative ties to the West Bank with the U.S.'s recognition of the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people forced Rabin to seek an end to the violence through negotiation and dialogue with the PLO.

In 1990 to 1992, Rabin again served as a Knesset member and sat on the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee.

In 1992 Rabin was elected as chairman of the Labor Party, winning against Shimon Peres. In the elections that year his party, strongly focusing on the popularity of its leader, managed to win a clear victory over the Likud of incumbent Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir. However the left wing bloc in the Knesset only won an overall narrow majority, facilitated by the disqualification of small nationalist parties that did not manage to pass the electoral threshold. Rabin formed the first Labor led government in fifteen years, supported by a coalition with Meretz, a left wing party, and Shas, a Mizrahi ultra - orthodox religious party.

Rabin played a leading role in the signing of the Oslo Accords, which created the Palestinian National Authority and granted it partial control over parts of the Gaza Strip and West Bank. Prior to the signing of the accords, Rabin received a letter from PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat renouncing violence and officially recognizing Israel, and on the same day, 9 September 1993, Rabin sent Arafat a letter officially recognizing the PLO.

After the announcement of the Oslo Accords there were many protest demonstrations in Israel objecting to the Accords. As these protests dragged on, Rabin insisted that as long as he had a majority in the Knesset he would ignore the protests and the protesters. In this context he said, "they (the protesters) can spin around and around like propellers" but he would continue on the path of the Oslo Accords. Rabin's parliamentary majority rested on non - coalition member Arab support. Rabin also denied the right of American Jews to object to his plan for peace, calling any dissent "chutzpah".

After the historical handshake with Yasser Arafat, Rabin said, on

behalf of the Israeli people: "We who have fought against you, the

Palestinians, we say to you today, in a loud and a clear voice, enough

of blood and tears ... enough!" During this term of office, Rabin also oversaw the signing of the Israel - Jordan Treaty of Peace in 1994.

For his role in the creation of the Oslo Accords, Rabin was awarded the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize, along with Yasser Arafat and Shimon Peres. The Accords greatly divided Israeli society, with some seeing Rabin as a hero for advancing the cause of peace and some seeing him as a traitor for giving away land they viewed as rightfully belonging to Israel. Many Israelis on the right wing often blame him for Jewish deaths in terror attacks, attributing them to the Oslo agreements.

Rabin was also awarded the 1994 Ronald Reagan Freedom Award by the former president's wife, former First Lady

Nancy Reagan. The award is only given to "those who have made

monumental and lasting

contributions to the cause of freedom worldwide," and who "embody

President Reagan's lifelong belief that one man or woman truly can make a

difference.".

On the evening of November 4, 1995 (12th of Heshvan on the Hebrew Calendar), Rabin was assassinated by Yigal Amir, a radical right wing Orthodox Jew who opposed the signing of the Oslo Accords. Rabin had been attending a mass rally at the Kings of Israel Square (Now Rabin Square) in Tel Aviv, held in support of the Oslo Accords. When the rally ended, Rabin walked down the city hall steps towards the open door of his car, at which point Amir fired three shots at Rabin with a semi - automatic pistol. Two shots hit Rabin, and the third lightly injured Yoram Rubin, one of Rabin's bodyguards. Rabin was rushed to nearby Ichilov Hospital, where he died on the operating table of blood loss and a punctured lung within 40 minutes. Amir was immediately seized by Rabin's bodyguards. He was later tried, found guilty, and sentenced to life imprisonment. After an emergency cabinet meeting, Israel's foreign minister, Shimon Peres, was appointed as acting Israeli prime minister.

Rabin's assassination came as a great shock to the Israeli public and much of the rest of the world. Hundreds of thousands of Israelis thronged the square where Rabin was assassinated to mourn his death. Young people, in particular, turned out in large numbers, lighting memorial candles and singing peace songs. Rabin's funeral was attended by many world leaders, among them U.S. president Bill Clinton, Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating, Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak and King Hussein of Jordan. Clinton delivered a eulogy whose final words were in Hebrew – "Shalom, Haver" (Hebrew: שלום חבר, lit. Goodbye, Friend).

The square where he was assassinated, Kikar Malkhei Yisrael (Kings of Israel Square), was renamed Rabin Square in his honor. Many other streets and public institutions in Israel have also subsequently been named after him. After his assassination, Rabin was hailed as a national symbol and came to embody the Israeli peace camp ethos, despite his military career and hawkish views earlier in life. He is buried on Mount Herzl. In November 2000, his wife Leah died and was buried alongside him.

There is much debate regarding the background of Rabin's assassination. There are a number of conspiracy theories related to the assassination of Rabin.

After Rabin's assassination, his daughter Dalia Rabin - Pelossof

entered into politics and was elected to the Knesset in 1999 as part of

the Center Party. In 2001, she served as Israel's Deputy Minister of Defense.

The Knesset has set the 12th of Heshvan, the murder date according to the Hebrew calendar, as the official memorial day of Rabin. An unofficial but widely followed memorial date is 4 November, the date according to the Gregorian calendar.

In 1995 the Israeli Postal Authority issued a commemorative Rabin stamp.

The Yitzhak Rabin Center was founded in 1997 by an act of the Knesset, to create "[a] Memorial Center for Perpetuating the Memory of Yitzhak Rabin." It carries out extensive commemorative and educational activities emphasizing the ways and means of democracy and peace.

Mechinat Rabin, an Israeli pre-army preparatory program for training recent high school graduates in leadership prior to their IDF service, was established in 1998.

Many cities and towns in Israel have named streets, neighborhoods, schools, bridges and parks after Rabin. Also two government office complexes and two synagogues are named after Yitzhak Rabin. Outside Israel, there are streets named after him in Bonn, Berlin and New York and parks in Montreal, Paris, Rome and Lima. The community Jewish high school in Ottawa is also named after him.

The Cambridge University Israel Society host its annual academic lecture in honor of Yizhak Rabin.

Reggae singer Alpha Blondy has recorded a single called "Yitzhak Rabin" in memory of the Israeli prime minister.

In 2005, he was voted the greatest Israeli of all time, in a poll by the Israeli news website Ynet to determine whom the general public considered the 200 Greatest Israelis.

Fawzi al-Qawuqji (Arabic: فوزي القاوقجي; January 19, 1890 – June 5, 1977) was a leading Arab nationalist military figure in the interwar period, based in Germany, and allied to Nazi Germany during World War II, who served as the Arab Liberation Army (ALA) field commander during the 1948 Palestine War.

Fawzi al-Qawuqji was born in 1890 into a Turkmen family in the city

of Tripoli, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire.

In 1912, he graduated from the military academy in Istanbul. Gilbert

Achcar calls him "Arab nationalism's leading military figure in the

interwar period... served as a commander in all the Arab national

battles of the period."

He served as a captain (Yuzbashi) in the 12th Ottoman corps garrison

in Mosul, and in several battles during the First World War, including

at Qurna in Iraq and at Beersheba in Ottoman Palestine. He was decorated

with the Ottoman Majidi Medal for his role in these battles. He was

also awarded the German Iron Cross, second class, for his service

fighting alongside General Otto von Kreiss' Prussians, who had opposed

the British in Palestine during World War I.

The Ottoman Empire collapsed after World War I. Al-Qawuqji supported

the independence of the short-lived Arab Kingdom of Syria. In 1920, he

fought at the Battle of Maysalun, serving in the army of King Faisal as a

captain (ra'is khayyal) in a squadron commanded by Taha al-Hashimi.

After the unsuccessful outcome of the campaign to establish the Arab

Kingdom of Syria, Syria became a French Mandate. Al-Qawuqji then joined

the 'Syrian Legion' (also known as the French - Syrian Army) which had

been created by the French mandatory authorities. Al-Qawuqji received

formal training at the French École spéciale militaire de Saint-Cyr.

He became commander of a cavalry squadron in Hama.

During the rebellion of 1925 – 1927, he deserted the French Army to join

the rebellion, leading the uprising in Hama in early October 1925. Al-Qawuqji remained an outlaw thereafter.

Shakib Arslan brought al-Qawuqji to the Hejaz to help train the army of

Saudi monarch Abdul - Aziz. Al-Qawuqji relates that he was unimpressed

with Abdul - Aziz, depicting him as self-infatuated and suspicious, who

disappointingly attempted to justify his collaboration with the

British.

In 1936, al-Qawuqji began fighting the British and the Jewish

population in Mandatory Palestine in actions that would become known as

the 1936 – 39 Arab revolt in Palestine. He represented the Iraqi Society

for the Defense of Palestine, which was separate from forces under the

control of Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Haj Amin Husseini. Al-Qawuqji

resigned his commission in the Iraqi army and his position at the Royal

Military College to lead approximately fifty armed guerrillas into

Mandatory Palestine. In June he contacted Fritz Grobba, who was

acting as German ambassador to Iraq. This was probably al-Qawuqji's

first encounter with a representative of Nazi Germany. In August, he

commanded about 200 volunteers from Iraq, Syria, Transjordan, and the

Samaria region of Palestine. His title was 'Supreme Commander of the

Arab Revolution in South - Syrian Palestine.' He operated four units,

(Iraqi, Syrian, Druze and Palestinian) in the Nablus - Tulkaram - Jenin

triangle until the end of October. The military performance of

al-Qawuqji's troops became hampered by internal dissensions and

animosity between him and Grand Mufti Husseini, the Arab Higher

Committee, and the Mufti's kinsman Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni, who

commanded forces that were active in the area around Jerusalem. On

26 October 1936, al-Qawuqji crossed the Jordan River with his troops

into Transjordan. A few weeks later he returned to Iraq.

Although al-Qawuqji and Grand Mufti al-Husseini had periods of

considerable friction and discord, particularly during the 1936 – 39 Arab

revolt in Palestine, the two men subsequently reached a

rapprochement. Al-Qawuqji followed the Mufti from Lebanon to Iraq in

October 1939, along with other members of the Mufti's entourage,

including Jamal al-Husayni, Rafiq al-Tamimi, and Sheikh Hasan Salama.

Al-Qawuqji became the Mufti's military advisor in the 'Arab Committee'

that Haj Amin Husseini formed in Baghdad. Husseini's group, including,

al-Qawuqji, played critical roles in the pro-Axis coup. His

frequently demonstrated prowess won him fame among the Arab population

and the esteem of Haj Amin Husseini. His popular following, however, was

not altogether to the Mufti's liking. He was prominent in the

Kingdom of Iraq during the Rashid Ali coup of 1941 and, during the

subsequent Anglo - Iraqi War, he again fought against the British.

Al-Qawuqji led approximately 500 "irregulars" in the area between Rutbah

and Ramadi. He established a reputation as bold fighter. He was

also known to either execute or mutilate his prisoners. After the

Rashid Ali regime collapsed, al-Qawuqji and his irregular forces were

targeted for destruction by the Mercol flying column and were chased out

of Iraq. While still in Iraq, a British plane strafed and almost killed

him.

After suffering serious wounds fighting the British in Iraq,

al-Qawuqji was transported to Vichy French-held Syria, and then made his

way to Nazi Germany. He remained in Germany for the remainder of

World War II, recuperated from his wounds, and married a German

woman.

Al-Qawuqji's sojourn in Germany has been the subject of considerable

controversy. Gilbert Achcar recounts stories of conflicts during his

Berlin period:

In his memoirs, he tells how, during his stay in

hospital, he came under heavy pressure from German civilian and military

officials to declare his allegiance to the Führer. He even had an

altercation with an SS officer who proffered threats when al-Qawuqji

insisted that Germany first formally acknowledge the Arab's right to

independence. The next day, his son died of poisoning. al-Qawuqji,

convinced that the Nazis had murdered the young man, refused to take

part in the funeral they organized.

Dr. Achcar reports that al-Qawuqji was as bewildered by rivalries

between competing Arab leaders (Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini and

exiled Iraqi former Prime Minister Rashid Ali) as by the Axis

foot dragging over support for Arab nationalist goals. He opposed

incorporating Arab units into the Axis armed forces, since he preferred

their formation into an independent Arab nationalist army.

In May 1942, after the Axis powers signed secret documents to support

the Arab nationalists, al-Qawuqji expressed dissatisfaction with the

results, commenting that they were "just symbolic and not an

agreement."

He was awarded the rank of a colonel of the Wehrmacht (German Army),

and given a captain to act as his aide, along with a chauffeured car,

and an apartment near the clinic at Hansa. His expenses were paid by

Wehrmacht High Command and by Rashid Ali's Foreign Minister. The Germans

used al-Qawuqji's name and reputation extensively in their

propaganda.

In Germany al-Qawuqji continued to oppose the Allies in cooperation with

other Arabs who were allied with the Axis powers, including the two

competing leaders of the pro-Nazi Arab factions, Grand Mufti Husseini

and former Iraqi Prime Minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani. In June 1941,

Wehrmacht High Führer Directive No. 30 and the "Instructions for Special

Staff F" (Sonderstab F) designated the Wehrmacht's central agency for

all issues that affected the Arab world. General der Flieger Hellmuth

Felmy, who was appointed central authority for all Arab affairs

concerning the Wehrmacht under the terms of this "Directive No. 30",

wrote about al-Qawuqji's 'active interest' and support of the military

training of Arabs by the Nazis:

Thus a number of the volunteers had already secretly

contacted Fauzi Kaikyi, the Syrian army leader. After his escape by

plane from the British, Fauzi had established himself in Berlin and

begun to take an active interest in the Arabs at Sunium.

In July 1941 al-Qawuqji wrote a memorandum addressed to General

Felmy. This memorandum's subject was the need for German - Arab

alliance in Iraq, and included discussions of geography, desert warfare,

and combined propaganda efforts directed against Jews. Al-Qawuqji

was officially transferred to Sonderstab F after he was fully recovered

from the wounds he received fighting against the British in Iraq.

Gen. Felmy's memoirs (written after the war when he was a prisoner of

the allies and published by the US Army) mention the political conflicts

between the 'chieftains' (Grand Mufti Husseini and former Iraqi Prime

Minister Rashid Ali) among Arab receiving military training in Greece,

and their consequent contact with al-Qawuqji. He consistently

campaigned for the formation of an independent Arab nationalist army

that would fight as German allies, rather than incorporate Arabs under

the German command structure. On 4 September 1941 al-Qawuqji told a

comrade in Syria "I will come with Arab and German troops to help

you."

In 1945, he was captured by Soviet forces, and reportedly held prisoner until February 1947.

In 1947 al-Qawuqji traveled to Egypt via France, and proclaimed that he was "at the disposition of the Arab people should they call on [him] to take up arms again." In August he threatened that, should the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine vote go the wrong way, “we will have to initiate total war. We will murder, wreck and ruin everything standing in our way, be it English, American or Jewish"

After the UN Partition vote, the Arab League

appointed him to be field commander of the Arab Liberation Army (ALA)

in the 1948 Palestine War. This appointment was opposed by Haj Amin

Husseini, who had appointed his own kinsman Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni as the commander of the Army of the Holy War.

The execution of the 1948 Palestine War was marked by the personal,

family, and political rivalry between al-Qawuqji (who fought mainly in

northern Palestine) and al-Husayni, who fought mostly in the Jerusalem

area.

In early March 1948, al-Qawuqji moved some of his forces from the

Damascus area and crossed (unmolested by British troops) into Palestine

over the Allenby Bridge, leading hundreds of Arab and Bosnian

volunteers in a column of twenty-five trucks. The British

troops' inaction infuriated General Sir Gordon MacMillan, who stated

that al-Qawudji should not be allowed "to go openly rampaging over

territory in which Britain considered herself a sovereign power."

General MacMillan did not want to confront al-Qawudji's force, however,

since he saw "no point in getting a lot of British soldiers killed in

that kind of operation."

Inside Mandatory Palestine al-Qawuqji commanded a few thousand armed men

who had infiltrated the area. They were grouped into several regiments

concentrated in Galilee and around Nablus. Al-Qawuqji told his

troops that the purpose was "ridding Palestine of the Zionist

plague". According to Collins and LaPierre, he anticipated a short

campaign, and announced:

"I have come to Palestine to stay and fight until

Palestine is a free and united Arab country or until I am killed and

buried here," ... His aim, he declared, borrowing the slogan that was

becoming the leitmotiv of the Arab leadership, was "to drive all the

Jews into the sea."

In April 1948, the ALA mounted a major attack on the kibbutz Mishmar

HaEmek which sat near the strategic road that connected Haifa to Jenin,

and was surrounded by Arab villages. On 4 April al-Qawuqji initiated

the first use of artillery during the war by directing his seven 75 and

105 mm field guns to fire on the kibbutz for a 36-hour barrage. During

this battle al-Qawuqji issued a number of announcements that were

subsequently proven false. In the first 24-hours he announced victory,

on 8 April he announced he had taken Mishmar HaEmek, and after the

battle was lost he claimed the Jews had been assisted by non-Jewish

Soviet troops and bombers. Copies of these mendacious telegrams are

preserved in the Jordanian archives. The Haganah and Palmach

counter-attacked and the ALA were routed. The battle was over by 16

April, and most of the Arabs in the area fled, disheartened by the

defeat of the ALA or demoralized by the Jewish victory. The remaining

minority were expelled from the surrounding Arab villages by Jewish

forces.

In July, al-Qawuqji launched a rolling offensive of counterattacks,

focusing on Ilaniya (Sejera), a Jewish settlement deep in ALA territory.

Although he deployed armored cars and a battery of 75 mm artillery to

support the ALA infantry, his troops suffered from lack of artillery

ammunition and host of other deficiencies. The opposing Golani Twelfth

Battalion withstood the attack, inflicting heavy losses on the ALA. The

battle ended on 18 July, with the ALA losing the Arab village of Lubiya,

which had been their main base in Central Eastern Galilee.

The ALA established control of upper central Galilee, from the

Sakhnin – Arabe – Deir Hanna line through Majd al-Krum up to the Lebanese

border until October 1948. On 22 October, the date of the third UN

Security Council ceasefire order, the ALA attacked Sheikh Abd,a hilltop

overlooking Kibbutz Manara and put the kibbutz under siege. Al-Qawudji

told the UN observers that he demanded depopulation of nearby Kibbutz

Yiftah forces, and a diminution of the Jewish forces in Manara. The

Jewish forces responded by demanding that ALA withdraw from its

positions. Al-Qawuqji rejected these counter-demands. The Jewish forces

then informed the United Nations that in view of al-Qawuqji's actions it

did not feel encumbered by the UN's cease-fire order, and on 24 October

launched Operation Hiram. Historian Benny Morris concludes that

although the Israelis had planned for Operation Hiram, they may not have

launched this campaign without the justification provided by

al-Qawuqji's military provocations. The result was that the ALA were

driven from their positions by force, and the Arab forces lost all of

upper Galilee, even though this had been assigned to the Arabs by the UN

Partition Plan. On 30 October the Jewish Carmeli Brigade retook Sheikh

Abd from the ALA, who had abandoned the position. Shortly thereafter the

last of the ALA forces were driven out of the Galilee and al-Qawuqji

escaped to Lebanon.

After the end of the war, al-Qawuqji moved to Syria and lived in Damascus, Beirut and Tripoli.