<Back to Index>

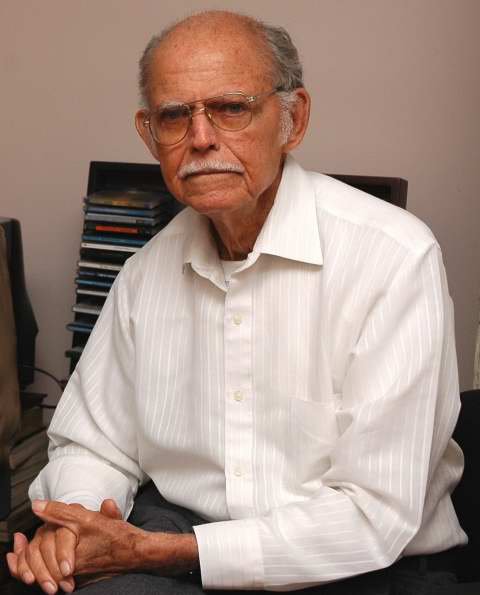

- Cuban Revolutionary Huber Matos Benítez, 1918

PAGE SPONSOR

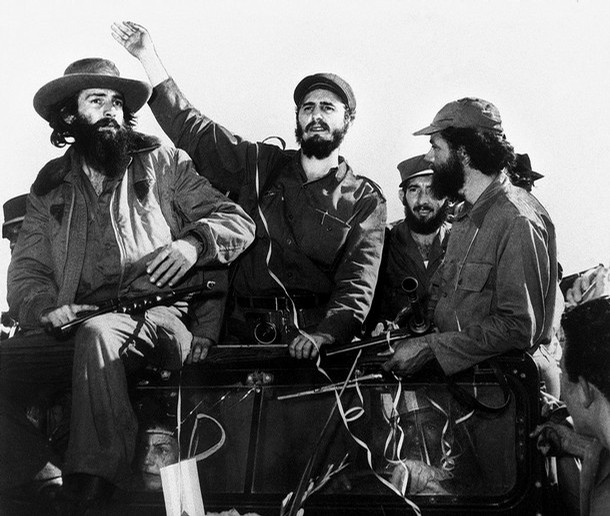

Huber Matos Benítez (November 26, 1918 - February 27, 2014) was a Cuban revolutionary who assisted Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and members of the 26th of July Movement in successfully overthrowing the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista as part of the Cuban Revolution.

He had opposed Batista since the general's effective coup in 1952,

which he regarded as unconstitutional, but became increasingly critical

of the movement's shift towards Marxist

principles, and closening ties with leaders of the Communist Party of

Cuba.

Convicted of "treason and sedition" by the new Castro regime, he would

spend 20 years in prison (1959 – 1979) before being released in 1979. He

then divided his time between Miami, Florida, and Costa Rica while

continuing to protest the policies of the Cuban government.

He was born in Yara, in Oriente Province.

In July 1959, Matos made public denunciations of the direction the revolution was taking, with openly anti - communist speeches in Camagüey. This led to a series of disputes between Castro, at that time Prime Minister of Cuba, and President Manuel Urrutia Lleó. Shortly thereafter, Castro replaced Urrutia with the Minister of Revolutionary Laws, Osvaldo Dorticós Torrado. Given his past concerns, Matos found the move troubling and decided to tender his resignation in a letter to Castro. On July 26, Castro and Matos met at the Hilton Hotel in Havana. The revolutionary leader was in a rather upbeat mood, as over a million people, including several thousand peasants, had flocked to the capital to celebrate the passage of the Agrarian Reform Law.

According to Matos, Castro told him, "'Your resignation is not acceptable at this point. We still have too much work to do,' he said. 'I admit that Raúl and Che are flirting with Marxism... but you have the situation under control... Forget about resigning... But if in a while you believe the situation is not changing, you have the right to resign.'"

In September 1959, Matos wrote, "Communist influence in the

government has continued to grow. I have to leave power as soon as

possible. I have to alert the Cuban people as to what is happening." On

October 19, he sent a second letter of resignation to Castro. Two days

later, Castro sent fellow revolutionary Camilo Cienfuegos

to arrest Matos. During the subsequent meeting between Cienfuegos and

Matos, who had grown close during the revolution, Matos says he warned

his young colleague that he believed he had been sent to make the arrest

so that forces allied with Matos might kill Camilo Cienfuegos. The

young revolutionary had become quite popular in the months following the

march on Havana, as such, Matos says it was Castro's intent to

eliminate any perceived competition.

Cienfuegos, however, is recorded as having supported the arrest of

Matos, which is why he had been sent. Cienfuegos mysteriously

disappeared en-route back to Havana after the securing of Matos and his

military adjutants in late October 1959. Some people hint at foul play

by either Castro or Matos, but most historians agree it was probably an

accident. Communists would later claim Matos was working in conjunction with persons such as Tony Varona, Carlos Prío,

and Manuel Artime with the plans for a counter - revolution organized

by the American Central Intelligence Agency under Frank Sturgis. After

the capture of Matos, the operation eventually evolved into the Bay of

Pigs Invasion.

The same day Matos was arrested, Miami Cuban exile Pedro Luis Díaz Lanz, former air force chief of staff under Castro, dropped leaflets into Havana that called for the removal of all Communists from the government. In response, Castro called for a show of hands at a political rally in favor of executing the two dissidents. The crowd responded with "Paredón" ("To the wall.")

Following the rally, Castro called a government meeting to determine Matos's fate. Che and Raúl favored execution, and three ministers who questioned Castro's version of events were immediately replaced by government loyalists. In the end, however, Castro decided against execution, explaining that "I don't want to turn him into a martyr."

A trial that began on December 11, 1959, found Matos guilty of "treason and sedition" and sentenced him to twenty years imprisonment, most of which were spent at the Isla de la Juventud, where Castro had been imprisoned in 1953. According to Matos, "prison was a long agony from which I emerged alive because of God's will. I had to go on hunger strikes, mount other types of protests. Terrible. On and off, I spent a total of sixteen years in solitary confinement, constantly being told that I was never going to get out alive, that I had been sentenced to die in prison. They were very cruel, to the fullest extent of the word... I was tortured on several occasions, I was subjected to all kinds of horrors, all kinds, including the puncturing of my genitals. Once during a hunger strike a prison guard tried to crush my stomach with his boot... Terrible things."

Matos was released from prison on October 21, 1979, having served out

his full term. He was reunited with his wife and children, who had left

Cuba during the 1960s, in Costa Rica.

They then moved to Miami. Mr. Matos, and

his son Huber Matos Jr., became active participants in the U.S. based

opposition to the Castro regime. He wrote a book about his experiences, Cómo llegó la noche (How the Night Came). The book is available in Spanish and in French (Et la nuit est tombée).

In October 1993 Huber Matos' son, Huber Matos Jr., was indicted along

with 11 other individuals in a $3.3 million medicare fraud case

involving a Miami clinic, Florida Medical & Diagnostic Center Inc.,

co-owned by Matos Jr. and Juana Mayda Perez Batista. Matos Sr. denounced

the charges against his son as a "lie to discredit me, my son and CID".

Matos Jr. lived in Costa Rica and as a Costa Rican citizen could not be

extradited to the U.S. for trial. In 1995, the 11 co-defendants plead

guilty to a variety of fraud charges.

Matos founded the Huber Matos Foundation for Democracy, a Jacksonville,

Florida-based organization whose goal is to "foster democratic rule,

human rights, social justice and education in Latin America". Most of

the organization's efforts and resources are invested in "promoting

democracy in Cuba".

Matos died at the age of 95 in Miami, Florida.