<Back to Index>

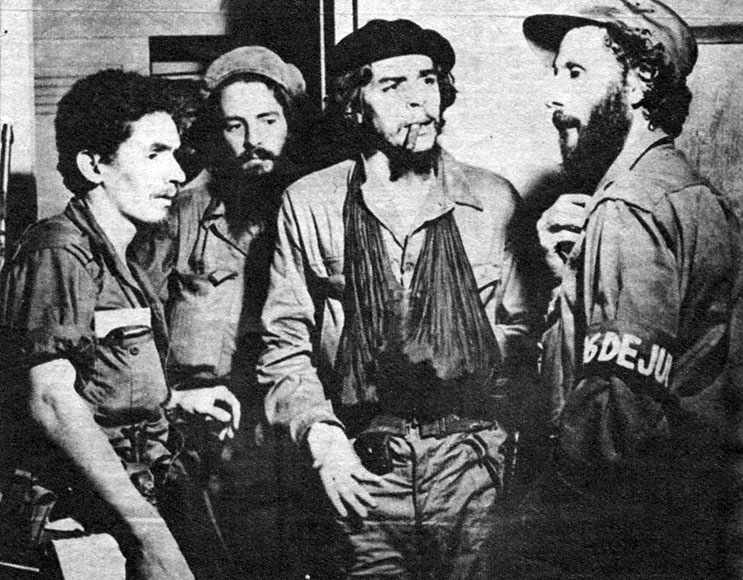

- Editor of the "Revolución" Carlos Franqui, 1921

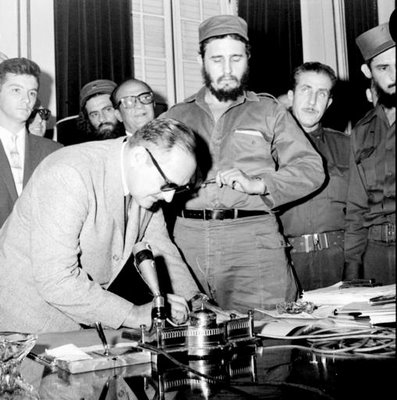

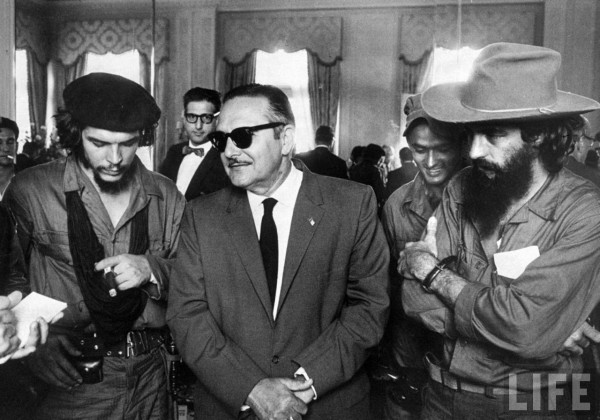

- President of Cuba Manuel Urrutia Lleó, 1901

PAGE SPONSOR

Carlos Franqui (December 4, 1921 – April 16, 2010) was a Cuban writer, poet, journalist, art critic and political activist. After the Fulgencio Batista coup in 1952, he became involved with the "Movimiento 26 de Julio" which was directed by Fidel Castro. Upon the success of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, he was placed in charge of Revolución, which became an official paper. After differences with the regime, he left Cuba with his family and in 1968 officially broke with the government when he signed a letter condemning the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. He became a vocal critic of the Castro government, writing frequently until his death on April 16, 2010.

Born in a cane field, he was able to enter a vocational school, where he joined the Communist Party of Cuba. He gave up the opportunity to enter the University of Havana to become a professional organizer for the party at the age of 20. After successfully organizing the party in several small towns, he broke with the organization and became an unaffiliated leftist.

He turned to journalism to make a living, where his voracious reading

provided him with a much better education than he would have received

in the university. During this time Franqui became involved in several

literary and artistic movements and developed friendships with Cuban

artists, including writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante and painter Wifredo Lam.

Franqui broke ranks with the Cuban Communist Party in the late 1940s, but he remained an unaffiliated leftist. After the Fulgencio Batista coup in 1952, he became involved with the "Movimiento 26 de Julio" which was directed by Fidel Castro. His contribution to the movement included co-editing the underground newspaper Revolución in Havana, for which he was in charge of public information. One article in particular reported the landing of the Granma and the confirmation of Fidel Castro's safety in the Sierra Maestra. He was jailed and tortured by the police. On his release, he went into exile in Mexico and Florida, but was soon drafted by Castro into the Sierra Maestra to continue work on Revolución, the guerrilla movement's clandestine newspaper and Radio Rebelde, their clandestine radio station. He published a book of interviews, letters and personal thoughts, "Diary of the Cuban Revolution", in 1980.

Upon the success of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, he was placed in charge of Revolución, which became an official paper. During his tenure as editor, he maintained a degree of independence from the official line and emphasized the arts and literature, starting the literary supplement "Lunes de Revolución", which was directed by Guillermo Cabrera Infante and where high quality work by Cuban and international authors was featured. His position allowed him to travel extensively outside of Cuba. During his European travels, he met artists and intellectuals, such as Pablo Picasso, Miró, Calder, Jean - Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Julio Cortázar and many others. A significant number of these artists traveled to Cuba. One of the most memorable visits was that of Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, which is recounted in his book.

Due to his critical attitude, Franqui had frequent disagreements with

the government, which eventually led to his resignation from

"Revolución". The paper was closed a few months later. After his

resignation, Franqui dedicated himself to art, organizing the famous

"Salón de Mayo" exhibit in Havana (1967), where all leading artists in the world were represented.

Because of his dissident attitude, he continued to have problems with the Cuban government. Eventually, he was allowed to leave Cuba with his family and settled in Italy as an unpaid cultural representative of Cuba. In 1968, he officially broke with the Cuban government when he signed a letter condemning the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.

After his definitive exile, his literary production markedly increased. Franqui penned several major historical accounts of the Cuban Revolution, including, "El Libro de los Doce" (The Book about the Twelve) and "Diario de la Revolución Cubana" (The Diary of the Cuban Revolution). Yet, another facet of his literary opus were a number of poetry and graphic arts collections (for which he collaborated with Joan Miró, Antoni Tàpies, Alexander Calder, and others), several books of poetry, as well as several narrative works on art (some edited in Italian under pen names).

He continued to campaign against repression in Cuba and other countries. He was officially branded as a traitor by the Cuban government, which accused him of CIA ties. Also, many Cuban exiles shun Franqui because of his active role in the Cuban revolution.

In the early 1990s he moved to Puerto Rico, where he lived in semi - retirement. In 1996, he founded Carta de Cuba,

a quarterly journal featuring high quality work produced in Cuba by

independent journalists and writers. Franqui continued to edit the

publication until his death, which occurred on April 16, 2010 in Puerto

Rico.

Manuel Urrutia Lleó (December 8, 1901, Yaguajay, Las Villas, Cuba – 5 July 1981, Queens, New York, United States) was a liberal Cuban lawyer and politician. Urrutia campaigned against the Gerardo Machado government and the second presidency of Fulgencio Batista during the 1950s, before serving as president in the first revolutionary government of 1959. After only six months, Urrutia resigned his position due to a series of disputes with revolutionary leader Fidel Castro and emigrated to the United States shortly after.

Urrutia was a leading figure in the civic resistance movement against Batista's government during the Cuban Revolution, and was the agreed choice of future president among Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement as early as April 1958. In 1957 Urrutia had presided in court over a case in which members of the movement had been charged with "anti - government activities", ruling that the defendants had been acting within their rights. A year later, Urrutia visited the U.S. to gain support for the Cuban revolution, successfully lobbying for a halt of weapons shipments to Batista's forces. It was considered that the choice of Urrutia, an educated liberal and Christian, as president would be welcomed by the United States.

The Cuban Revolution gained victory on January 1, 1959, and Urrutia returned from exile in Venezuela to take up residence in the presidential palace. Urrutia's new revolutionary government consisted largely of Cuban political veterans and pro-business liberals including José Miró, who was appointed as Urrutia's prime minister.

Once in power, Urrutia swiftly began a program of closing all brothels, gambling outlets and the national lottery, arguing that these had long been a corrupting influence on the state. The measures drew immediate resistance from the large associated workforce. The disapproving Castro, then commander of Cuba's new armed forces, intervened to request a stay of execution until alternative employment could be found.

Disagreements also arose in the new government concerning pay cuts which were imposed on all public officials on Castro's demand. The disputed cuts included a reduction of the $100,000 a year presidential salary Urrutia had inherited from Batista. By February Castro had assumed the role of prime minister following the surprise resignation of Miró, strengthening his power and rendering Urrutia increasingly a figurehead president. As Urrutia's participation in the legislative process declined, other unresolved disputes between the two leaders continued to fester. Urrutia's belief in the restoration of elections was rejected by Castro, who felt that they would usher in a return to the old discredited system of corrupt parties and fraudulent balloting which marked the Batista era.

Urrutia was then accused by the Avance newspaper of buying a luxury villa, which was portrayed as a frivolous betrayal of the revolution and led to an outcry from the general public. Urrutia denied the allegation issuing a writ against the newspaper in response. The story further increased tensions between the various factions in the government, though Urrutia asserted publicly that he had "absolutely no disagreements" with Fidel Castro. Urrutia attempted to distance the Cuban government (including Castro) from the growing influence of the Communists within the administration, making a series of critical public comments against the latter group. Whilst Castro had not openly declared any affiliation with the Cuban communists, Urrutia had been a declared anti - Communist since they had refused to support the insurrection against Batista, stating in an interview, "If the Cuban people had heeded those words, we would still have Batista with us ... and all those other war criminals who are now running away".

On July 17, 1959, Conrado Bécquer, the sugar workers' leader demanded Urrutia's resignation. Castro himself resigned as Prime Minister of Cuba in protest, but later that day appeared on television to deliver a lengthy denouncement of Urrutia, claiming that Urrutia "complicated" government, and that his "fevered anti - Communism" was having a detrimental effect. Castro's sentiments received widespread support as organized crowds surrounded the presidential palace demanding Urrutia's resignation, which was duly received. On July 23, Castro resumed his position as premier and appointed Osvaldo Dorticós as the new president.

After leaving his post Urrutia sought asylum in the embassy of Venezuela before settling in Queens, New York, United States. Urrutia worked as a high school Spanish teacher until his death in 1981.