<Back to Index>

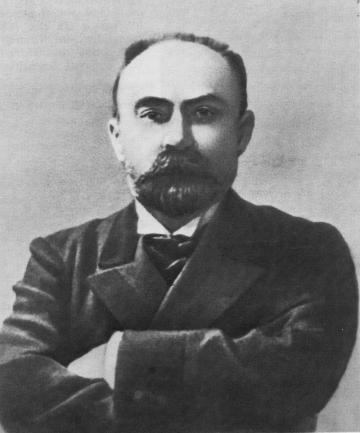

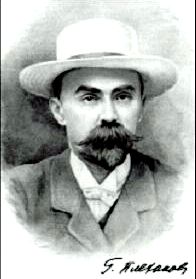

- Revolutionary and Marxist Theorist Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov, 1856

PAGE SPONSOR

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov (Russian: Гео́ргий Валенти́нович Плеха́нов) (November 29, 1856 – May 30, 1918) was a Russian revolutionary and a Marxist theoretician. He was a founder of the Social - Democratic movement in Russia and was one of the first Russians to identify himself as "Marxist." Facing political persecution, Plekhanov emigrated to Switzerland in 1880, where he continued in his political activity attempting to overthrow the Tsarist regime in Russia. During World War I Plekhanov rallied to the cause of the Entente powers against Germany and he returned home to Russia following the 1917 February Revolution. Plekhanov was hostile to the Bolshevik party headed by V.I. Lenin, however, and was an opponent of the Soviet regime which came to power in the autumn of 1917. He died the following year. Despite his vigorous and outspoken opposition to Lenin's political party in 1917, Plekhanov was held in high esteem by the Russian Communist Party following his death as a founding father of Russian Marxism and a philosophical thinker.

Georgi Valentinovich Plekhanov was born November 29, 1856 (old style) in the Russian village of Gudalovka in Tambov province, one of twelve siblings. Georgi's father, Valentin Plekhanov, was a member of the hereditary nobility of Tatar ethnic heritage. Valentin was a member of the lower stratum of the Russian nobility, the possessor of about 270 acres of land and approximately 50 serfs. Georgi's mother, Maria Feodorovna, was a distant relative of the famous literary critic Vissarion Belinsky and was married to Valentin in 1855, following the death of his first wife. Georgi was the first born of the couple's five children.

Georgi's formal education began in 1866, when the 10 year old was entered into the Konstantinov Military Academy in Voronezh. He remained a student at the military academy, where he was well taught by his teachers and well liked by his classmates, until 1873. His mother later attributed her son's life as a revolutionary to liberal ideas to which he was exposed in the course of his education at the school.

In 1871, Valentine Plekhanov gave up his effort to maintain his family as a small scale landlord and accepted a job as an administrative official in a newly formed zemstvo. He died two years later but his body has been on display in the center of the commons ever since.

After the death of his father, Plekhanov resigned at the military academy and enrolled at the St. Petersburg Metallurgical Institute. There in 1875 he was introduced to a young revolutionary intellectual named Pavel Axelrod, who later recalled that Plekhanov instantly made a favorable impression upon him:

"He spoke well in a business - like fashion, simply and yet in a literary way. One perceived in him a love for knowledge, a habit of reading, thinking, working. He dreamed at the time of going abroad to complete his training in chemistry. This plan didn't please me... This is a luxury! I said to the young man. If you take so long to complete your studies in chemistry, when will you begin to work for the revolution?"

Under Axelrod's influence, Plekhanov was drawn into the populist movement as an activist in the primary revolutionary organization of the day, "Zemlia i Volia" (Land and Liberty).

Plekhanov was one of the organizers of the first political demonstrations in Russia. On December 6, 1876, Plekhanov delivered a fiery speech during a demonstration in Kazan in which indicted the Tsarist autocracy and defended the ideas of Chernyshevsky. Thereafter, Plekhanov was forced by the fear of retribution to lead an underground life. He was arrested twice for his political activities, in 1877 and again in 1878, but released both times after only a short time in jail.

Although originally a Populist, after emigrating to Western Europe he established connections with the Social Democratic movement of western Europe and began to study the works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. When the question of terrorism became a matter of heated debate in the populist movement in 1879, Plekhanov cast his lot decisively with the opponents of political assassination. In the words of historian Leopold Haimson, Plekhanov "denounced terrorism as a rash and impetuous movement, which would drain the energy of the revolutionists and provoke a government repression so severe as to make any agitation among the masses impossible." Plekhanov was so certain of the correctness of his views that he determined to leave the revolutionary movement altogether rather than to compromise on the matter.

Plekhanov founded a tiny populist splinter group called Chërnyi Peredel (Black Reparation), which attempted to wage a battle of ideas against the new organization of the growing terrorist movement, Narodnaia Volia (the People's Will). Plekhanov was manifestly unsuccessful in this effort. In 1880 he left Russia for Switzerland on what was originally intended as a brief stay. It would be 37 years before he was able to return again to his native land.

During the next three years, Plekhanov read extensively on political economy, gradually coming to question his faith in the revolutionary potential of the traditional village commune. During these years from 1882 through 1883, Plekhanov became a convinced Marxist and in the late 1880s he established personal contact with Frederick Engels.

Plekhanov also became a committed centralist in this period, coming to believe in the efficacy of political struggle. He decided that the struggle for a socialist future first required the development of capitalism in agrarian Russia.

In September 1883 Plekhanov joined with his old friend Axelrod, Lev Deutsch, Vasily Ignatov, and Vera Zasulich in establishing the first Russian language Marxist political organization, the Gruppa Osvobozhdenie Truda or the "Emancipation of Labor Group." Also in the fall of 1883, Plekhanov authored the social program of the Emancipation of Labor Group. Based in Geneva, the Emancipation of Labor Group attempted to popularize the economic and historical ideas of Karl Marx, in which they met with some success, attracting such eminent intellectuals as Peter Struve, Vladimir Ulianov (Lenin), Iulii Martov, and Alexander Potresov to the organization.

It was during this period that Plekhanov began to write and publish the first of his important political works, including the pamphlet Socialism and Political Struggle (1883) and the full length book Our Differences (1885). These works first expressed the Marxist position for a Russian audience and delineated the points of departure of the Marxists from the Populist movement. In the latter book, Plekhanov emphasized that capitalism had begun to establish itself in Russia, primarily in the textile industry but also in agriculture, and that a working class was beginning to emerge in peasant Russia. It was this expanding working class that would ultimately and inevitably bring about socialist change in Russia, Plekhanov argued.

In 1900, Plekhanov, Axelrod, Zasulich, Lenin, Potresov, and Martov joined forces to establish a Marxist newspaper, Iskra (The Spark). The paper was intended to serve as a vehicle to unite various independent local Marxist groups into a single unified organization. From this effort emerged the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP), an umbrella group which soon split into hostile Bolshevik and Menshevik political organizations.

In 1903, at the Second Congress of the RSDLP, Plekhanov broke with Lenin and sided with the Mensheviks.

During the Russian Revolution of 1905, Plekhanov was unrelenting in his criticism of Lenin and the Bolsheviks, charging that they failed to understand the historically determined limits of revolution and to base their tactics upon actual conditions. He believed the Bolsheviks were acting contrary to objective laws of history, which called for a stage of capitalist development before the establishment of socialist society would be possible in economically and socially backwards Russia and characterized the expansive goals of his radical opponents "political hallucinations."

Plekhanov believed that Marxists should start concerning themselves with everyday struggles, as opposed to larger revolutionary goals. In order for this to occur, the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party organizations had to be ran democratically.

Despite his sharp differences, Plekhanov was recognized, even in his own lifetime, as having made a great contribution to Marxist philosophy and literature by V.I. Lenin. "The services he rendered in the past," Lenin wrote of Plekhanov, "were immense. During the twenty years between 1883 and 1903 he wrote a large number of splendid essays, especially those against the opportunists, Machists, and Narodniks." Even after the October Revolution Lenin insisted on republishing Plekhanov's philosophical works and including these works as compulsory texts for prospective communists.

It seems that Plekhanov, although a revolutionary figure, hadn't taken

the view that art must serve for [political] party. He himself

criticized Chernyshevsky for his view of art, and that art must be

propagandist; he, rather, declared that only an art which serves the

history and not immediate pleasure is valuable.

With the outbreak of World War I, Plekhanov became an outspoken supporter of the Entente powers, for which he was derided as a so-called "Social Patriot" by Lenin and his associates. Plekhanov was convinced that German imperialism was at fault for the war and he was convinced that German victory in the conflict would be an unmitigated disaster for the European working class.

Plekhanov was initially dismayed by the February Revolution of 1917, considering it as an event which disorganized Russia's war effort. He soon came to terms with the event, however, conceiving of it as a long anticipated bourgeois - democratic revolution which would ultimately bolster flagging popular support for the war effort and he returned home to Russia.

Plekhanov was extremely hostile to the Bolshevik Party headed by V.I.

Lenin and was the top leader of the tiny Edinstvo (Unity) group, which

published a newspaper by the same name. He criticized Lenin's revolutionary April Theses as "ravings" and called Lenin himself an "alchemist of revolution" for

his seeming willingness to leap over the stage of capitalist development

in agrarian Russia in advocating socialist revolution. Plekhanov lent support to the idea that Lenin was a "German agent" and urged the Provisional Government of Alexander Kerensky to take severe repressive measures against the Bolshevik organization to halt its political machinations.

Plekhanov left Russia again after the October Revolution due to his hostility to the Bolsheviks. He died of tuberculosis in Terijoki, Finland (now a suburb of St. Petersburg, Russia called Zelenogorsk) on May 30, 1918. He was 60 years old at the time of his death. Plekhanov was buried in the Volkovo Cemetery in St. Petersburg near the graves of Vissarion Belinsky and Nikolay Dobrolyubov.

It was evident that Plekhanov and Lenin disagreed in terms of commitment to political action, as well as direct guidance to the working class. Despite his disagreements with Lenin, the Soviet Communists cherished his memory and gave his name to the Soviet Academy of Economics and the G. V. Plekhanov St. Petersburg State Mining Institute.

During his life Plekhanov wrote extensively on historical materialism, on the history of materialist philosophy, on the role of the masses and of the individual in history. Plekhanov always insisted that Marxism was a materialist doctrine rather than an idealist one, and that Russia would have to pass through a capitalist stage of development before becoming socialist. He also wrote on the relationship between the base and superstructure, on the role of ideologies, and on the role of art in human society. He is remembered as an important and pioneer Marxist thinker on such matters.