<Back to Index>

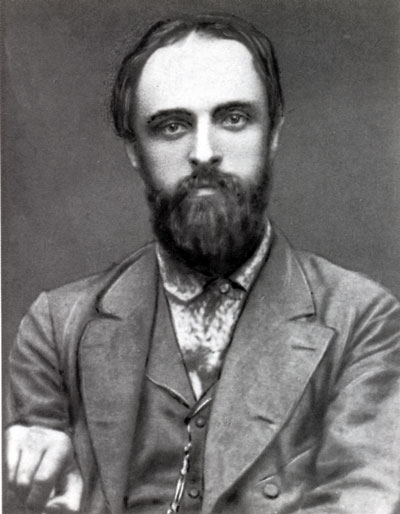

- Leader of the Mensheviks Alexander Nikolayevich Potresov, 1869

- Political Economist, Philosopher and Editor Pyotr Berngardovich Struve, 1870

PAGE SPONSOR

Alexander Nikolayevich Potresov (Russian: Александр Николаевич Потресов) (September 1(13), 1869, Moscow – July 11, 1934, Paris) was a Russian social democrat and one of the leaders of Menshevism. He was one of six original editors of the newspaper Iskra.

A.N. Potresov was born into a noble family; his father was a Major General. He studied physics, mathematics and law at the University of St. Petersburg. As a student he came into contact with revolutionary groups. In the early 1890s he converted from Populism to Marxism and joined the secret Social Democratic circles of P.B. Struve and I.O. Martov. In 1892 he contacted the exiled Emancipation of Labor group of G.V. Plekhanov and arranged for some of Plekhanov's writings to be published in Russia legally. The Russian government was at that time more concerned about the revolutionary populism of Narodnaya Volya (The People's Will) than about Plekhanov, whose group was opposed to populism.

In 1896 Potresov helped found the St. Petersburg Union of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, one of the nuclei of the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDRP). Other members of the St. Petersburg Union included Martov and V.I. Lenin. In 1897, Potresov was arrested and exiled to Vyatka province. After his release in 1900 he left Russia and lived mostly in Germany, where he had good contacts among the German Social Democrats and among the Russian exiles. He grew close to P.B. Akselrod and V.I. Zasulich.

In 1898, Potresov married his fellow exile, Ekaterina Tulinvoia ,

Together with Plekhanov, Akselrod, Zasulich, Lenin and Martov, Potresov launched the journal Iskra (The Spark), whose mission it was to defend orthodox Marxism (as Plekhanov understood it) against the various heresies of Economism and Revisionism that were then current among Russian Social Democrats. In 1898 Potresov helped found the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDRP). However, in 1901 - 02 Potresov fell seriously ill and could do little editorial work. Lenin proposed to reduce the editorial board to himself, Plekhanov and Martov, discarding the less productive Akselrod, Zasulich and Potresov. This caused some bad blood between Lenin and those he proposed to dismiss. In 1903, when the RSDRP split into Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, Potresov sided with the latter.

By the end of 1903 it was Lenin who had left Iskra, while Potresov was back on the editorial board. He was invaluable to the Mensheviks because of his good contacts to the German Social Democrats, and was largely responsible for the fact that most SPD leaders tended to sympathize with the Mensheviks (although officially they were studiously neutral). However, tensions soon developed between Potresov and Plekhanov. Plekhanov, who had voted with the Bolsheviks in 1903, was pressing for a reunification of the RSDRP. In this he had the support of the Germans. Potresov, supported by Zasulich, considered co-operation with Lenin impossible. Potresov and Zasulich left the Iskra board.

The Revolution of 1905 brought Potresov back to Russia, where he edited the Menshevik papers Nachalo (Beginning) and Nevskii Golos (New Voice). He also attended the Menshevik's' party congresses in 1906 and 1907. After the defeat of the Revolution, Potresov sympathized with the so-called 'Liquidators' who wanted to suspend illegal revolutionary work and concentrate on trade union work (legal since 1906) and elections to the Duma. This course was diametrically opposed by Lenin, but it also put him at odds with 'Party Mensheviks' like Martov. Nevertheless, Liquidationism was a strong current among Mensheviks, and Potresov, as editor of the Liquidationist journal Nacha Zariia (Our Charge), was one of its most prominent theoreticians. In addition to his journalism, Potresov wrote historical and sociological essays. He was one of the editors and contributors to the four volume The Social Movement in Russia in the Early 20th Century (1909 – 14).

In 1914, Potresov immediately adopted a Defensist position. He was supported by Plekhanov but abandoned by most Mensheviks, even most Menshevik Defensists, who were wary of Potresov's unqualified support for 'war to victory'. Potresov, however, argued that a victory of the Entente over the Central Powers would be a victory of Western democracy over Prussian militarism, and would benefit the socialist movement everywhere. He propagated these views in the journal Nache Delo (Our Cause). Potresov was nevertheless highly critical of the government for its incompetent conduct of the war. In 1915 this led to the closing of his journal and his exile from Petrograd. He was, however, allowed to live in Moscow and there continued his journalism. Potresov sought to assist the war effort by joining the Moscow Military Industrial Committee.

In 1917 he welcomed the February Revolution because it got rid of the Tsar's incompetent leadership. But Potresov's demand to continue the war effort at all costs alienated him from most Mensheviks. Even the Revolutionary Defensists who dominated the soviets kept him at arms' length. During preparations for the elections to the Constituent Assembly, Potresov threatened to withdraw from the RSDRP and head a separate list. Potresov vehemently opposed the October Revolution. In 1918 he withdrew from the RSRP and joined the Union for the Salvation of Russia, a group uniting right wing Mensheviks, SRs, Popular Socialists. He later regretted this collaboration.

In 1918 the Bolsheviks arrested Potresov for his involvement in that committee. In 1925 he was permitted to leave Soviet Russia for medical reasons. He lived first in Berlin and then in Paris, battling illness. Potresov viewed the Soviet Union not as a socialist state but as a thoroughly reactionary oligarchy, a point of view that alienated him from most Mensheviks. He contributed regularly to A.F. Kerensky's journal Dni (Day). He expected the imminent collapse of communism and urged all anti - Bolshevik forces to unite.

Potresov died in Paris on July 11, 1934, as a consequence of an operation.

Peter (or Pyotr or Petr) Berngardovich Struve (Пётр Бернгардович Струве; January 26, 1870, Perm – February 22, 1944, Paris) was a Russian political economist, philosopher and editor. He started out as a Marxist, later became a liberal and after the Bolshevik revolution joined the White movement. From 1920 he lived in exile in Paris, where he was a prominent critic of Russian Communism.

Peter Struve is probably the best known member of the Russian branch of the Struve family. Son of Bernhard Struve (Astrakhan and later Perm governor) and grandson of astronomer Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve, he entered the Natural Sciences Department of the University of Saint Petersburg in 1889 and transferred to its law school in 1890. While there, he became interested in Marxism, attended Marxist and narodniki (populist) meetings (where he met his future opponent Vladimir Lenin) and wrote articles for legally published magazines — hence the term Legal Marxism, whose chief proponent he became. In September 1893 Struve was hired by the Finance Ministry and worked in its library, but was fired on June 1, 1894 after an arrest and a brief detention in April – May of that year. In 1894 he also published his first major book, Kriticheskie zametki k voprosu ob ekonomicheskom razvitii Rossii (Critical Notes on the Economic Development of Russia) in which he defended the applicability of Marxism to Russian conditions against populist critics.

In 1895 Struve finished his degree and wrote an Open letter to Nicholas II on behalf of the Zemstvo. He then went abroad for further studies, where he attended the 1896 International Socialist Congress in London and befriended famous Russian revolutionary exile Vera Zasulich.

After returning to Russia Struve became one of the editors of the successive Legal Marxist magazines Novoye Slovo (The New Word, 1897), Nachalo (The Beginning, 1899) and Zhizn (1899 – 1901). Struve was also the most popular speaker at the Legal Marxist debates at the Free Economic Society in the late 1890s - early 1900s in spite of his often impenetrable - to - laymen arguments and unkempt appearance. In 1898 Struve wrote the Manifesto of the newly formed Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. However, as he later explained:

- Socialism, to tell the truth, never aroused the slightest emotion in me, still less attraction... Socialism interested me mainly as an ideological force -- which... could be directed either to the conquest of civil and political freedoms or against them

By 1900, Struve had become a leader of the revisionist, i.e., moderate, wing of Russian Marxists. Struve and Mikhail Tugan - Baranovsky represented the moderates during the negotiations with Julius Martov, Alexander Potresov and Vladimir Lenin, the leaders of the party's radical wing, in Pskov in March 1900. In late 1900, Struve went to Munich and again held lengthy talks with the radicals between December 1900 and February 1901. The two sides eventually reached a compromise which included making Struve the editor of Sovremennoe Obozrenie (Contemporary Review), a proposed supplement to the radicals' magazine Zaria (Dawn), in exchange for his help in securing financial support from Russian liberals. The plan was frustrated by Struve's arrest at the famous Kazan Square demonstration on March 4, 1901 immediately upon his return to Russia. Struve was banished from the capital and, like other demonstrators, was offered to choose his own place of exile. He chose Tver, a center of Zemstvo radicalism.

In 1902 Struve secretly left Tver and went abroad, but by then the radicals had abandoned the idea of a joint magazine and Struve's further evolution from socialism to liberalism would have made collaboration difficult anyway. Instead he founded an independent liberal semi - monthly magazine Osvobozhdenie (Liberation) with the help of liberal intelligentsia and the radical part of Zemstvo. The magazine was financed by D.E. Zhukovsky and was at first published in Stuttgart, Germany (July 1, 1902 – October 15, 1904). In mid 1903, after the founding of the liberal Soyuz Osvobozhdeniya (Union of Liberation), the magazine became the Union's official organ and was smuggled into Russia, where it enjoyed considerable success. When German police, under pressure from Okhrana, raided the premises in October 1904, Struve moved his operations to Paris and continued publishing the magazine for another year (October 15, 1904 – October 18, 1905) until the October Manifesto proclaimed freedom of the press in Russia.

In October 1905 Struve returned to Russia, and became a co-founder of the liberal Constitutional Democratic party and a member of its Central Committee. In 1907 he represented the party in the Second State Duma.

After the Duma's dissolution on June 3, 1907, Struve concentrated on his work at Russkaya Mysl (Russian Thought), a leading liberal newspaper, of which he had been publisher and de facto editor - in - chief since 1906.

Struve was the driving force behind Vekhi (Milestones, 1909), a groundbreaking and controversial anthology of essays critical of the intelligentsia and its rationalistic and radical traditions. As Russkaya Mysl editor, Struve rejected Andrey Bely's seminal novel Petersburg, which he apparently saw as a parody of revolutionary intellectuals.

With the outbreak of World War I

in 1914 Struve adopted a position of support for the government, and in

1916 he resigned from the Constitutional Democratic party's Central

Committee over what he saw as the party's excessive opposition to the

government in a time of war.

In May 1917, after the February Revolution of 1917 which overthrew monarchy in Russia, Struve was elected to the Russian Academy of Sciences, of which he would remain a member until a Bolshevik engineered expulsion in 1928.

Immediately after the October Revolution of 1917, Struve went to the South of Russia where he joined the Volunteer Army's Council.

In early 1918 he returned to Moscow, where he lived under an assumed name for most of the year, contributed to Iz Glubiny (variously translated as De Profundis, From the Deep or From the Depths, 1918), a follow up to Vekhi, and published several other notable articles on the causes of the revolution.

With the Russian Civil War raging and his life in danger Struve had to flee; and after a three month journey arrived in Finland, where he negotiated with Gen. Nikolai Yudenich and the Finnish leader Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim before leaving for Western Europe. Struve represented Gen. Anton Denikin's anti - Bolshevik government in Paris and London in 1919, before returning to Denikin controlled territories in the South of Russia, where he edited a leading newspaper of the White Movement. With Denikin's resignation after the Novorossisk debacle and Gen. Pyotr Wrangel's rise to the top in early 1920, Struve became Wrangel's foreign minister.

With the defeat of Wrangel's army in November 1920 Struve left for Bulgaria, where he relaunched Russkaya Mysl under the aegis of the emigre "Russko - Bolgarskoe knigoizdatel'stvo" publishing house, and then for Paris, where he remained until his death in 1944.

His children were prominent in the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia.

Peter Struve's son Gleb Struve' (1898 – 1985) was one of the most prominent Russian critics of the 20th century. He taught at the University of California, Berkeley, and befriended Vladimir Nabokov in the 1920s.

Pyotr's grandson, Nikita Struve (b. 1931), is a professor at a Paris university and an editor of several Russian language periodicals published in Europe.