<Back to Index>

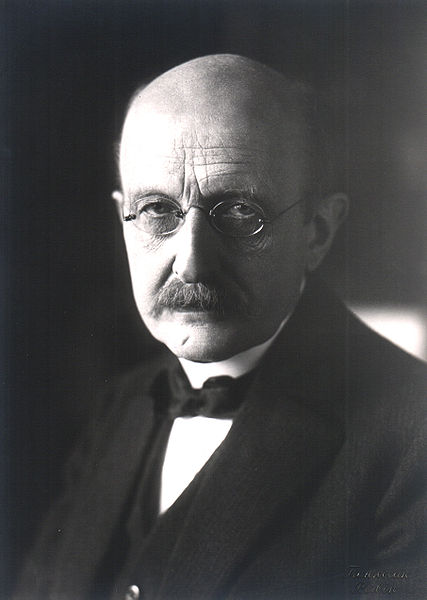

- Physicist Joseph John "J.J." Thomson, 1856

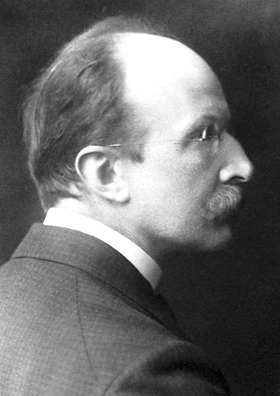

- Physicist Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck, 1858

PAGE SPONSOR

Sir Joseph John "J. J." Thomson, OM, FRS (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was a British physicist and Nobel laureate. He is credited with discovering electrons and isotopes, and inventing the mass spectrometer. Thomson was awarded the 1906 Nobel Prize in Physics for the discovery of the electron and for his work on the conduction of electricity in gases.

Joseph John Thomson was born in 1856 in Cheetham Hill, Manchester, England. His mother, Emma Swindells, came from a local textile family. His father, Joseph James Thomson, ran an antiquarian bookshop founded by a great - grandfather from Scotland (hence the Scottish spelling of his surname). He had a brother two years younger than he, Frederick Vernon Thomson.

His early education took place in small private schools where he demonstrated great talent and interest in science. In 1870 he was admitted to Owens College. Being only 14 years old at the time, he was unusually young. His parents planned to enroll him as an apprentice engineer to Sharp - Stewart & Co., a locomotive manufacturer, but these plans were cut short when his father died in 1873. He moved on to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1876. In 1880, he obtained his BA in mathematics (Second Wrangler and 2nd Smith's prize) and MA (with Adams Prize) in 1883. In 1884 he became Cavendish Professor of Physics. One of his students was Ernest Rutherford, who would later succeed him in the post. In 1890 he married Rose Elisabeth Paget, daughter of Sir George Edward Paget, KCB, a physician and then Regius Professor of Physic at Cambridge. He had one son, George Paget Thomson, and one daughter, Joan Paget Thomson, with her. One of Thomson's greatest contributions to modern science was in his role as a highly gifted teacher, as seven of his research assistants and his aforementioned son won Nobel Prizes in physics. His son won the Nobel Prize in 1937 for proving the wavelike properties of electrons.

He was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1906, "in recognition of the great merits of his theoretical and experimental investigations on the conduction of electricity by gases." He was knighted in 1908 and appointed to the Order of Merit in 1912. In 1914 he gave the Romanes Lecture in Oxford on "The atomic theory". In 1918 he became Master of Trinity College, Cambridge, where he remained until his death. He died on August 30, 1940 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, close to Sir Isaac Newton.

Thomson was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 12 June 1884 and was subsequently President of the Royal Society from 1915 to 1920.

Several scientists, such as William Prout and Norman Lockyer, had suggested that atoms were built up from a more fundamental unit, but they envisaged this unit to be the size of the smallest atom, hydrogen. Thomson, in 1897, was the first to suggest that the fundamental unit was over 1000 times smaller than an atom, suggesting the sub-atomic particles now known as electrons. Thomson discovered this through his explorations on the properties of cathode rays. Thomson made his suggestion on 30 April 1897 following his discovery that Lenard rays could travel much further through air than expected for an atomic - sized particle. He estimated the mass of cathode rays by measuring the heat generated when the rays hit a thermal junction and comparing this with the magnetic deflection of the rays. His experiments suggested not only that cathode rays were over 1000 times lighter than the hydrogen atom, but also that their mass was the same whatever type of atom they came from. He concluded that the rays were composed of very light, negatively charged particles which were a universal building block of atoms. He called the particles "corpuscles", but later scientists preferred the name electron which had been suggested by George Johnstone Stoney in 1894, prior to Thomson's actual discovery.

In April 1897 Thomson had only early indications that the cathode rays could be deflected electrically (previous investigators such as Heinrich Hertz had thought they could not be). A month after Thomson's announcement of the corpuscle he found that he could deflect the rays reliably by electric fields if he evacuated the discharge tubes to very low pressures. By comparing the deflection of a beam of cathode rays by electric and magnetic fields he was then able to get more robust measurements of the mass to charge ratio that confirmed his previous estimates. This became the classic means of measuring the charge and mass of the electron.

Thomson believed that the corpuscles emerged from the atoms of the trace gas inside his cathode ray tubes.

He thus concluded that atoms were divisible, and that the corpuscles

were their building blocks. To explain the overall neutral charge of the

atom, he proposed that the corpuscles were distributed in a uniform sea

of positive charge; this was the "plum pudding" model — the electrons

were embedded in the positive charge like plums in a plum pudding

(although in Thomson's model they were not stationary, but orbiting

rapidly).

In 1912, as part of his exploration into the composition of canal rays, Thomson and his research assistant F. W. Aston channeled a stream of ionized neon through a magnetic and an electric field and measured its deflection by placing a photographic plate in its path. They observed two patches of light on the photographic plate, which suggested two different parabolas of deflection, and concluded that neon is composed of atoms of two different atomic masses (neon-20 and neon-22), that is to say of two isotopes. This was the first evidence for isotopes of a stable element; Frederick Soddy had previously proposed the existence of isotopes to explain the decay of certain radioactive elements.

JJ Thomson's separation of neon isotopes by their mass was the first

example of mass spectrometry, which was subsequently improved and

developed into a general method by F. W. Aston and by A. J. Dempster.

In 1905 Thomson discovered the natural radioactivity of potassium.

In 1906 Thomson demonstrated that hydrogen had only a single electron per atom. Previous theories allowed various numbers of electrons.

Earlier, physicists debated whether cathode rays were immaterial like light ("some process in the aether") or had mass and were composed of particles. The aetherial hypothesis was vague, but the particle hypothesis was definite enough for Thomson to test.

Thomson first investigated the magnetic deflection of cathode rays.

Cathode rays were produced in the side tube on the left of the apparatus

and passed through the anode into the main bell jar, where they were

deflected by a magnet. Thomson detected their path by the fluorescence

on a squared screen in the jar. He found that whatever the material of

the anode and the gas in the jar, the deflection of the rays was the

same, suggesting that the rays were of the same form whatever their

origin.

While supporters of the aetherial theory accepted the possibility that negatively charged particles are produced in Crookes tubes, they believed that they are a mere byproduct and that the cathode rays themselves are immaterial. Thomson set out to investigate whether or not he could actually separate the charge from the rays.

Thomson constructed a Crookes tube

with an electrometer set to one side, out of the direct path of the

cathode rays. Thomson could trace the path of the ray by observing the

phosphorescent patch it created where it hit the surface of the tube.

Thomson observed that the electrometer registered a charge only when he

deflected the cathode ray to it with a magnet. He concluded that the

negative charge and the rays were one and the same.

In May – June 1897 Thomson investigated whether or not the rays could be deflected by an electric field. Previous experimenters had failed to observe this, but Thomson believed their experiments were flawed because their tubes contained too much gas.

Thomson constructed a Crookes tube with a near perfect vacuum. At the start of the tube was the cathode from which the rays projected. The rays were sharpened to a beam by two metal slits – the first of these slits doubled as the anode, the second was connected to the earth. The beam then passed between two parallel aluminum plates, which produced an electric field between them when they were connected to a battery. The end of the tube was a large sphere where the beam would impact on the glass, created a glowing patch. Thomson pasted a scale to the surface of this sphere to measure the deflection of the beam.

When the upper plate was connected to the negative pole of the

battery and the lower plate to the positive pole, the glowing patch

moved downwards, and when the polarity was reversed, the patch moved

upwards.

In his classic experiment, Thomson measured the mass - to - charge ratio of the cathode rays by measuring how much they were deflected by a magnetic field and comparing this with the electric deflection. He used the same apparatus as in his previous experiment, but placed the discharge tube between the poles of a large electromagnet. He found that the mass to charge ratio was over a thousand times lower than that of a hydrogen ion (H+), suggesting either that the particles were very light and/or very highly charged.

The details of the calculation are:

The electric deflection is given by Θ = Fel/mv2 where Θ is the angular electric deflection, F is applied electric intensity, e is the charge of the cathode ray particles, l is the length of the electric plates, m is the mass of the cathode ray particles and v is the velocity of the cathode ray particles.

The magnetic deflection is given by φ = Hel/mv where φ is the angular magnetic deflection and H is the applied magnetic field intensity.

The magnetic field was varied until the magnetic and electric deflections were the same, when Θ = φ and Fel/mv2= Hel/mv. This can be simplified to give m/e = H2l/FΘ. The electric deflection was measured separately to give Θ and H, F and l were known, so m/e could be calculated.

As the cathode rays carry a charge of negative electricity, are deflected by an electrostatic force as if they were negatively electrified, and are acted on by a magnetic force in just the way in which this force would act on a negatively electrified body moving along the path of these rays, I can see no escape from the conclusion that they are charges of negative electricity carried by particles of matter.—J. J. Thomson

As to the source of these particles, Thomson believed they emerged from the molecules of gas in the vicinity of the cathode.

If, in the very intense electric field in the neighbourhood of the cathode, the molecules of the gas are dissociated and are split up, not into the ordinary chemical atoms, but into these primordial atoms, which we shall for brevity call corpuscles; and if these corpuscles are charged with electricity and projected from the cathode by the electric field, they would behave exactly like the cathode rays.—J. J. Thomson

Thomson imagined the atom as being made up of these corpuscles

orbiting in a sea of positive charge; this was his plum pudding model.

This model was later proved incorrect when Ernest Rutherford showed that

the positive charge is concentrated in the nucleus of the atom.

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck, ForMemRS, (April 23, 1858 – October 4, 1947) was a German physicist who discovered quantum physics, initiating a revolution in natural science and philosophy. He is regarded as the founder of quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

Planck came from a traditional, intellectual family. His

paternal great - grandfather and grandfather were both theology

professors in Göttingen; his father was a law professor in Kiel and

Munich; and his paternal uncle was a judge.

Planck was born in Kiel, Holstein, to Johann Julius Wilhelm Planck and his second wife, Emma Patzig. He was baptized with the name of Karl Ernst Ludwig Marx Planck; of his given names, Marx (a now obsolete variant of Markus or maybe simply an error for Max, which is actually short for Maximilian) was indicated as the primary name. However, by the age of ten he signed with the name Max and used this for the rest of his life.

He was the sixth child in the family, though two of his siblings were from his father's first marriage. Among his earliest memories was the marching of Prussian and Austrian troops into Kiel during the Danish - Prussian war of 1864. In 1867 the family moved to Munich, and Planck enrolled in the Maximilians gymnasium school, where he came under the tutelage of Hermann Müller, a mathematician who took an interest in the youth, and taught him astronomy and mechanics as well as mathematics. It was from Müller that Planck first learned the principle of conservation of energy. Planck graduated early, at age 17. This is how Planck first came in contact with the field of physics.

Planck was gifted when it came to music. He took singing lessons and

played piano, organ and cello, and composed songs and operas. However,

instead of music he chose to study physics.

The Munich physics professor Philipp von Jolly advised Planck against going into physics, saying, "in this field, almost everything is already discovered, and all that remains is to fill a few holes." Planck replied that he did not wish to discover new things, but only to understand the known fundamentals of the field, and so began his studies in 1874 at the University of Munich. Under Jolly's supervision, Planck performed the only experiments of his scientific career, studying the diffusion of hydrogen through heated platinum, but transferred to theoretical physics.

In 1877 he went to Berlin for a year of study with physicists Hermann von Helmholtz and Gustav Kirchhoff and mathematician Karl Weierstrass. He wrote that Helmholtz was never quite prepared, spoke slowly, miscalculated endlessly, and bored his listeners, while Kirchhoff spoke in carefully prepared lectures which were dry and monotonous. He soon became close friends with Helmholtz. While there he undertook a program of mostly self study of Clausius's writings, which led him to choose heat theory as his field.

In October 1878 Planck passed his qualifying exams and in February 1879 defended his dissertation, Über den zweiten Hauptsatz der mechanischen Wärmetheorie (On the second law of thermodynamics). He briefly taught mathematics and physics at his former school in Munich.

In June 1880 he presented his habilitation thesis, Gleichgewichtszustände isotroper Körper in verschiedenen Temperaturen (Equilibrium states of isotropic bodies at different temperatures).

With the completion of his habilitation thesis, Planck became an unpaid private lecturer in Munich, waiting until he was offered an academic position. Although he was initially ignored by the academic community, he furthered his work on the field of heat theory and discovered one after another the same thermodynamical formalism as Gibbs without realizing it. Clausius's ideas on entropy occupied a central role in his work.

In April 1885 the University of Kiel appointed Planck as associate professor of theoretical physics. Further work on entropy and its treatment, especially as applied in physical chemistry, followed. He proposed a thermodynamic basis for Svante Arrhenius's theory of electrolytic dissociation.

Within four years he was named the successor to Kirchhoff's position

at the University of Berlin — presumably thanks to Helmholtz's

intercession — and by 1892 became a full professor. In 1907 Planck was

offered Boltzmann's position in Vienna,

but turned it down to stay in Berlin. During 1909, as University of

Berlin professor, eight of his lectures were used by the Ernest Kempton

Adams Fund for Physical Research in Theoretical Physics at Columbia

University in New York City for a series of lectures translated by

Columbia University professor A. P. Wills. He retired from Berlin on

January 10, 1926, and was succeeded by Erwin Schrödinger.

In March 1887 Planck married Marie Merck (1861 – 1909), sister of a school fellow, and moved with her into a sublet apartment in Kiel. They had four children: Karl (1888 – 1916), the twins Emma (1889 – 1919) and Grete (1889 – 1917), and Erwin (1893 – 1945).

After the apartment in Berlin, the Planck family lived in a villa in Berlin - Grunewald, Wangenheimstrasse 21. Several other professors of Berlin University lived nearby, among them theologian Adolf von Harnack, who became a close friend of Planck. Soon the Planck home became a social and cultural center. Numerous well known scientists, such as Albert Einstein, Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner were frequent visitors. The tradition of jointly performing music had already been established in the home of Helmholtz.

After several happy years, in July 1909 Marie Planck died, possibly from tuberculosis. In March 1911 Planck married his second wife, Marga von Hoesslin (1882 – 1948); in December his third son Hermann was born.

During the First World War Planck's second son Erwin was taken prisoner by the French in 1914, while his oldest son Karl was killed in action at Verdun. Grete died in 1917 while giving birth to her first child. Her sister died the same way two years later, after having married Grete's widower. Both granddaughters survived and were named after their mothers. Planck endured these losses stoically.

In January 1945, Erwin, to whom he had been particularly close, was sentenced to death by the Nazi Volksgerichtshof because of his participation in the failed attempt to assassinate Hitler in July 1944. Erwin was executed on 23 January 1945.

- Wives: Marie Merck (m. 1887), Marga von Hoesslin (m. 1910)

- Children: Karl (1888 – 1916), twins Emma (1889 – 1919) and Grete (1889 – 1917), Erwin (1893 – 1945), Hermann (1911 – 1954)

In Berlin, Planck joined the local Physical Society. He later wrote about this time: "In those days I was essentially the only theoretical physicist there, whence things were not so easy for me, because I started mentioning entropy, but this was not quite fashionable, since it was regarded as a mathematical spook". Thanks to his initiative, the various local Physical Societies of Germany merged in 1898 to form the German Physical Society (Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft, DPG); from 1905 to 1909 Planck was the president.

Planck started a six semester course of lectures on theoretical physics, "dry, somewhat impersonal" according to Lise Meitner, "using no notes, never making mistakes, never faltering; the best lecturer I ever heard" according to an English participant, James R. Partington, who continues: "There were always many standing around the room. As the lecture room was well heated and rather close, some of the listeners would from time to time drop to the floor, but this did not disturb the lecture". Planck did not establish an actual "school"; the number of his graduate students was only about 20, among them:

- 1897 Max Abraham (1875 – 1922)

- 1904 Moritz Schlick (1882 – 1936)

- 1906 Walther Meissner (1882 – 1974)

- 1906 Max von Laue (1879 – 1960)

- 1907 Fritz Reiche (1883 – 1960)

- 1912 Walter Schottky (1886 – 1976)

- 1914 Walther Bothe (1891 – 1957)

In 1894 Planck turned his attention to the problem of black body radiation. He had been commissioned by electric companies to create maximum light from lightbulbs with minimum energy. The problem had been stated by Kirchhoff in 1859: "how does the intensity of the electromagnetic radiation emitted by a black body (a perfect absorber, also known as a cavity radiator) depend on the frequency of the radiation (i.e., the color of the light) and the temperature of the body?". The question had been explored experimentally, but no theoretical treatment agreed with experimental values. Wilhelm Wien proposed Wien's law, which correctly predicted the behavior at high frequencies, but failed at low frequencies. The Rayleigh – Jeans law, another approach to the problem, created what was later known as the "ultraviolet catastrophe", but contrary to many textbooks this was not a motivation for Planck.

Planck's first proposed solution to the problem in 1899 followed from what Planck called the "principle of elementary disorder", which allowed him to derive Wien's law from a number of assumptions about the entropy of an ideal oscillator, creating what was referred-to as the Wien – Planck law. Soon it was found that experimental evidence did not confirm the new law at all, to Planck's frustration. Planck revised his approach, deriving the first version of the famous Planck black body radiation law, which described the experimentally observed black body spectrum well. It was first proposed in a meeting of the DPG on October 19, 1900 and published in 1901. This first derivation did not include energy quantisation, and did not use statistical mechanics, to which he held an aversion. In November 1900, Planck revised this first approach, relying on Boltzmann's statistical interpretation of the second law of thermodynamics as a way of gaining a more fundamental understanding of the principles behind his radiation law. As Planck was deeply suspicious of the philosophical and physical implications of such an interpretation of Boltzmann's approach, his recourse to them was, as he later put it, "an act of despair ... I was ready to sacrifice any of my previous convictions about physics."

The central assumption behind his new derivation, presented to

the DPG

on 14 December 1900, was the supposition, now known as the Planck

postulate, that electromagnetic energy could be emitted only in

quantized form, in other words, the energy could only be a multiple of

an elementary unit  , where

, where  is Planck's constant, also known as Planck's action quantum (introduced already in 1899), and

is Planck's constant, also known as Planck's action quantum (introduced already in 1899), and  (the Greek letter nu, not the Roman letter v) is the frequency of the radiation. Note that the elementary units of energy discussed here are represented by

(the Greek letter nu, not the Roman letter v) is the frequency of the radiation. Note that the elementary units of energy discussed here are represented by  and not simply by

and not simply by  . Physicists now call these quanta photons, and a photon of frequency

. Physicists now call these quanta photons, and a photon of frequency  will have its own specific and unique energy. The amplitude of energy

at that frequency is then a function of the number of photons of that

frequency being produced per unit of time.

will have its own specific and unique energy. The amplitude of energy

at that frequency is then a function of the number of photons of that

frequency being produced per unit of time.

At first Planck considered that quantization was only "a purely formal assumption ... actually I did not think much about it..."; nowadays this assumption, incompatible with classical physics, is regarded as the birth of quantum physics and the greatest intellectual accomplishment of Planck's career (Ludwig Boltzmann had been discussing in a theoretical paper in 1877 the possibility that the energy states of a physical system could be discrete). Further interpretation of the implications of Planck's work was advanced by Albert Einstein in 1905 in connection with his work on the photoelectric effect — for this reason, the philosopher and historian of science Thomas Kuhn argued that Einstein should be given credit for quantum theory more so than Planck, since Planck did not understand in a deep sense that he was "introducing the quantum" as a real physical entity. Be that as it may, it was in recognition of Planck's monumental accomplishment that he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1918.

The discovery of Planck's constant enabled him to define a new universal set of physical units (such as the Planck length and the Planck mass), all based on fundamental physical constants.

Subsequently, Planck tried to grasp the meaning of energy quanta, but to no avail. "My unavailing attempts to somehow reintegrate the action quantum into classical theory extended over several years and caused me much trouble." Even several years later, other physicists like Rayleigh, Jeans, and Lorentz set Planck's constant to zero in order to align with classical physics, but Planck knew well that this constant had a precise nonzero value. "I am unable to understand Jeans' stubbornness — he is an example of a theoretician as should never be existing, the same as Hegel was for philosophy. So much the worse for the facts if they don't fit."

Max Born

wrote about Planck: "He was by nature and by the tradition of his

family conservative, averse to revolutionary novelties and skeptical

towards speculations. But his belief in the imperative power of logical

thinking based on facts was so strong that he did not hesitate to

express a claim contradicting to all tradition, because he had convinced

himself that no other resort was possible."

In 1905 the three epochal papers of the hitherto completely unknown Albert Einstein were published in the journal Annalen der Physik. Planck was among the few who immediately recognized the significance of the special theory of relativity. Thanks to his influence this theory was soon widely accepted in Germany. Planck also contributed considerably to extend the special theory of relativity.

Einstein's hypothesis of light quanta (photons), based on Philipp Lenard's 1902 discovery of the photoelectric effect, was initially rejected by Planck. He was unwilling to discard completely Maxwell's theory of electrodynamics. "The theory of light would be thrown back not by decades, but by centuries, into the age when Christian Huygens dared to fight against the mighty emission theory of Isaac Newton ..."

In 1910 Einstein pointed out the anomalous behavior of specific heat at low temperatures as another example of a phenomenon which defies explanation by classical physics. Planck and Nernst, seeking to clarify the increasing number of contradictions, organized the First Solvay Conference (Brussels 1911). At this meeting Einstein was able to convince Planck.

Meanwhile Planck had been appointed dean of Berlin University,

whereby it was possible for him to call Einstein to Berlin and establish

a new professorship for him (1914). Soon the two scientists became

close friends and met frequently to play music together.

At the onset of the First World War Planck endorsed the general excitement of the public, writing that, "Besides much that is horrible, there is also much that is unexpectedly great and beautiful: the smooth solution of the most difficult domestic political problems by the unification of all parties (and) ... the extolling of everything good and noble."

Nonetheless, Planck refrained from the extremes of nationalism. In 1915, at a time when Italy was about to join the Allied Powers, he voted successfully for a scientific paper from Italy, which received a prize from the Prussian Academy of Sciences, where Planck was one of four permanent presidents.

Planck also signed the infamous "Manifesto of the 93 intellectuals",

a pamphlet of polemic war propaganda (while Einstein retained a

strictly pacifistic attitude which almost led to his imprisonment, being

spared by his Swiss citizenship). But

in 1915 Planck, after several meetings with Dutch physicist Lorentz,

revoked parts of the Manifesto. Then in 1916 he signed a declaration

against German annexationism.

In the turbulent post war years, Planck, now the highest authority of German physics, issued the slogan "persevere and continue working" to his colleagues.

In October 1920 he and Fritz Haber established the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft (Emergency Organization of German Science), aimed at providing financial support for scientific research. A considerable portion of the monies the organization would distribute were raised abroad.

Planck also held leading positions at Berlin University, the Prussian Academy of Sciences, the German Physical Society and the Kaiser - Wilhelm - Gesellschaft (which in 1948 became the Max - Planck - Gesellschaft). During this time economic conditions in Germany were such that he was hardly able to conduct research.

During the interwar period, Planck became a member of the Deutsche Volks - Partei (German People's Party), the party of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Gustav Stresemann, which aspired to liberal aims for domestic policy and rather revisionistic aims for international politics.

Planck disagreed with the introduction of universal suffrage and later expressed the view that the Nazi dictatorship resulted from "the ascent of the rule of the crowds".

At the end of the 1920s Bohr, Heisenberg and Pauli had worked

out the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics, but it was

rejected by Planck, as well as Schrödinger, Laue, and Einstein. Planck

expected that wave mechanics

would soon render quantum theory — his own child — unnecessary. This

was

not to be the case, however. Further work only cemented quantum theory,

even against his and Einstein's philosophical revulsions. Planck

experienced the truth of his own earlier observation from his struggle

with the older views in his younger years: "A new scientific truth does

not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light,

but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation

grows up that is familiar with it."

When the Nazis seized power in 1933, Planck was 74. He witnessed many Jewish friends and colleagues expelled from their positions and humiliated, and hundreds of scientists emigrated from Germany. Again he tried the "persevere and continue working" slogan and asked scientists who were considering emigration to remain in Germany. He hoped the crisis would abate soon and the political situation would improve. There was also a deeper argument against emigration. Emigrating German non - Jewish scientists would need to look for academic positions abroad, but these positions better served Jewish scientists, who had no chance of continuing to work in Germany.

Hahn asked Planck to gather well known German professors in order to issue a public proclamation against the treatment of Jewish professors, but Planck replied, "If you are able to gather today 30 such gentlemen, then tomorrow 150 others will come and speak against it, because they are eager to take over the positions of the others." Under Planck's leadership, the Kaiser - Wilhelm - Gesellschaft (KWG) avoided open conflict with the Nazi regime, except concerning Fritz Haber. Planck tried to discuss the issue with Adolf Hitler but was unsuccessful. In the following year, 1934, Haber died in exile.

One year later, Planck, having been the president of the KWG since 1930, organized in a somewhat provocative style an official commemorative meeting for Haber. He also succeeded in secretly enabling a number of Jewish scientists to continue working in institutes of the KWG for several years. In 1936, his term as president of the KWG ended, and the Nazi government pressured him to refrain from seeking another term.

As the political climate in Germany gradually became more hostile, Johannes Stark, prominent exponent of Deutsche Physik ("German Physics", also called "Aryan Physics") attacked Planck, Sommerfeld and Heisenberg for continuing to teach the theories of Einstein, calling them "white Jews." The "Hauptamt Wissenschaft" (Nazi government office for science) started an investigation of Planck's ancestry, but all they could find out was that he was "1/16 Jewish."

In 1938 Planck celebrated his 80th birthday. The DPG held a celebration, during which the Max - Planck medal (founded as the highest medal by the DPG in 1928) was awarded to French physicist Louis de Broglie. At the end of 1938 the Prussian Academy lost its remaining independence and was taken over by Nazis (Gleichschaltung). Planck protested by resigning his presidency. He continued to travel frequently, giving numerous public talks, such as his talk on Religion and Science, and five years later he was sufficiently fit to climb 3,000 meter peaks in the Alps.

During the Second World War, the increasing number of Allied bombing campaigns against Berlin forced Planck and his wife to leave the city temporarily and live in the countryside. In 1942 he wrote: "In me an ardent desire has grown to persevere this crisis and live long enough to be able to witness the turning point, the beginning of a new rise." In February 1944 his home in Berlin was completely destroyed by an air raid, annihilating all his scientific records and correspondence. Finally, he got into a dangerous situation in his rural retreat because of the rapid advance of the Allied armies from both sides. After the end of the war he was brought to a relative in Göttingen.

Planck endured many personal tragedies after the age of 50. In 1909,

his first wife died after 22 years of marriage, leaving him with two

sons and twin daughters. Planck's oldest son, Karl, was killed in action

in 1916. His daughter Margarete died in childbirth in 1917, and another

daughter, Emma, married her late sister's husband and then also died in

childbirth, in 1919. During World War II, Planck's house in Berlin was

completely destroyed by bombs in 1944 and his youngest son, Erwin, was implicated in the attempt made on Hitler's life in the July 20 plot. Consequently, Erwin died at the hands of the Gestapo in 1945. Erwin's death destroyed Planck's will to live. By the end of the war, Planck, his second wife and his son by her, moved to Göttingen where he died on October 4, 1947.

Planck was very tolerant towards alternative views and religions. In a lecture on 1937 entitled "Religion und Naturwissenschaft" he suggested the importance of these symbols and rituals related directly with a believer's ability to worship God, but that one must be mindful that the symbols provide an imperfect illustration of divinity. He criticized atheism for being focused on the derision of such symbols, while at the same time warned of the over - estimation of the importance of such symbols by believers.

Max Planck said "All matter originates and exists only by virtue of a force which brings the particle of an atom to vibration and holds this most minute solar system of the atom together. We must assume behind this force the existence of a conscious and intelligent mind. This mind is the matrix of all matter" in 1944, indicating that he believed in some kind of God.

Planck regarded the scientist as a man of imagination and faith, "faith" interpreted as being similar to "having a working hypothesis". For example the causality principle isn't true or false, it is an act of faith. Thereby Planck may have indicated a view that points toward Imre Lakatos' research programs process descriptions, where falsification is mostly tolerable, in faith of its future removal.

On the other hand, Planck wrote, "... 'to believe' means 'to recognize as a truth,' and the knowledge of nature, continually advancing on incontestably safe tracks, has made it utterly impossible for a person possessing some training in natural science to recognize as founded on truth the many reports of extraordinary contradicting the laws of nature, of miracles which are still commonly regarded as essential supports and confirmations of religious doctrines, and which formerly used to be accepted as facts pure and simple, without doubt or criticism. The belief in miracles must retreat step by step before relentlessly and reliably progressing science and we cannot doubt that sooner or later it must vanish completely."

Six months before his death a rumor started that Planck had converted to Catholicism, but when questioned what had brought him to make this step, he declared that, although he had always been deeply religious, he did not believe "in a personal God, let alone a Christian God."