<Back to Index>

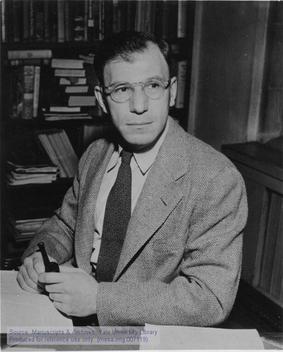

- Military Strategist Bernard Brodie, 1910

PAGE SPONSOR

Bernard Brodie (20 May 1910 – November 24, 1978) was an American military strategist well known for establishing the basics of nuclear strategy. Known as "the American Clausewitz," he was an initial architect of nuclear deterrence strategy and tried to ascertain the role and value of nuclear weapons after their creation.

Born in Chicago, Bernard Brodie was the third of four sons of Max and Esther (Bloch) Brodie, Jewish immigrants from the Russian Empire. His father was a fruit pedlar and Yiddish was the language of the household. Brodie graduated from the University of Chicago with a Ph.B. in 1932, and received a Ph.D. in 1940.

Brodie was an instructor at Dartmouth College from 1941 to 43. During World War II, he served in the U.S. Naval Reserve Bureau of Ordnance and at the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. He then taught at Yale University from 1945 to 1951, and worked at the RAND Corporation as a senior staff member between 1951 and 1966. Brodie was a full professor and taught Political Science and International Relations at UCLA from 1966 until his death in 1978.

He married Fawn McKay Brodie – who became a well known biographer of Richard Nixon, Joseph Smith, Thomas Jefferson and others – on August 28, 1936. They were the parents of three children.

Initially a theorist about naval power, Brodie shifted his focus to nuclear strategy after the creation of the nuclear bomb. His most important work, written in 1946, was entitled The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order, which laid down the fundamentals of nuclear deterrence strategy. He saw the usefulness of the atomic bomb was not in its deployment but in the threat of its deployment. In a now famous passage he said "Thus far, the chief purpose of our military establishment has been to win wars. From now on its chief purpose must be to avert them. It can have almost no other useful purpose." In the early fifties, he shifted out of academia and began work at the Rand Corporation where a stable of important strategists, Herman Kahn and others, developed the rudiments of nuclear strategy and war fighting theory.

While working at the RAND Corporation, Brodie wrote Strategy in the Missile Age (1959) which outlined the framework of deterrence. By arguing that preventative nuclear strikes would lead to escalation from limited to total war, Brodie concluded that deterrence through second strike capability would lead to a more secure outcome for both sides. Due to the virtual abandonment of first strike as a strategy, Brodie suggested investment in civil defense, which included the "hardening" of land based missile locations to ensure the strength of the second strike capability. The building of protected missile silos around the United States is a testament to this belief in second strike capability. It was also important for the second strike force to have first strike capabilities to provide the stasis necessary for deterrence. Brodie believed that the second strike force should not be targeted towards cities but towards military installations. This was meant to give the Soviets an opportunity to limit escalation and allow the United States to win the war. Brodie also advocated the funding of conventional military personnel as a means of ensuring communist containment through limited wars or to fight total war if deterrence fails.

Brodie, who had a fascination with Freud and psychoanalysis, sometimes used it to refer to his work in nuclear strategy. In an internally circulated memorandum at the RAND Corporation, Brodie compared his no cities / withhold plan to coitus interruptus, while the SAC plan was like "going all the way". Following those comments, fellow RAND scholar Herman Kahn told an assembled group of SAC officers "Gentlemen, you do not have a war plan. You have a Wargasm!". It is interesting to note that similar sexual imagery was liberally used in Stanley Kubrick's film Dr. Strangelove, a satire of Cold War nuclear strategy.

Brodie was also responsible, along with Michael Howard and Peter Paret,

for making the writings of Carl von Clausewitz more accessible to the

English speaking world. Brodie's incisive "A guide to the reading of On War"

in the Princeton translation of 1976 corrected most of the

misinterpretations of the Prussian's theory and provided students with

an accurate synopsis of this vital work.

- Sea Power in the Machine Age. Princeton University Press,1941 and 1943.

- A Layman’s Guide to Naval Strategy. Princeton University Press, 1942.

- The Absolute Weapon: Atomic Power and World Order. (editor and contributor), Harcourt, 1946.

- Strategy in the Missile Age. Princeton University Press, 1959.

- From Cross - Bow to H-Bomb. Dell, 1962; Indiana University Press (rev. ed.), 1973.

- Escalation and the Nuclear Option. Princeton University Press, 1966.

- Bureaucracy, Politics, and Strategy. University of California, 1968 (with Henry Kissinger).

- The Future of Deterrence in U.S. Strategy. Security Studies Project, University of California, 1968.

- War and Politics. Macmillan, 1973.

- A Guide to the Reading of "On War". Princeton University Press, 1976.