<Back to Index>

- Chief of the Okhrana Pyotr Ivanovich Rachkovsky, 1853

- Writer and Agent of the Okhrana Matvei Vasilyevich Golovinsky, 1865

PAGE SPONSOR

Pyotr Ivanovich Rachkovsky (Russian: Пётр Иванович Рачковский; 1853 – 1910) was chief of Okhrana, the secret service in Imperial Russia. He was based in Paris from March 1885 to November 1902.

After the assassination of Alexander II of Russia in 1881, the government moved against various revolutionary factions operating in emigration or hiding out in Russia. Rachkovsky's principal mission was to compromise Russia's growing revolutionary movement. The list of penetration agents hired by Rachkovsky included:

- Landesen (Abraham Hackelman), among the Narodnaya Volya terrorists in France and Switzerland

- Ignaty Kornfeld, among the Anarcho - Communists

- Prodeus, a well - known revolutionary, reporting on various revolutionary centers

- Ilya Drezhner, among the Social Democrats in Germany, Switzerland, and France

- Boleslaw Malankiewicz, among the Polish anarchists and terrorists in London

- Casimir Pilenas, a spotter for Scotland Yard recruited to work among the Latvian terrorists

- Zinaida Zhuchenko, among the Socialist Revolutionaries and their terrorist Fighting Unit

- Aleksandr Evalenko, assigned to New York City for work among the Jewish Bundists and terrorists

According to journalist Brian Doherty:

"Rachkovsky started as a possibly sincere, possibly duplicitous mover in St. Petersburg’s radical underground in the late 1870s, after having been dismissed (for leniency toward political exiles) from a job as a prosecutor for the czar’s government. He ended up running the show for the Okhrana, the Russian secret police, in Paris, where so many radicals considered dangerous to the czarist regime had immigrated. From 1885 until 1902, Rachkovsky was responsible for keeping anarchists under surveillance and on the run — and also, in many cases, financed and supplied with ideas. . . . “[P]rominent among his early initiatives were provocations designed to lure credulous émigrés into the most heinous crimes of which they may never have otherwise conceived.” Rachkovsky’s aim was to entrap his targets into committing acts that would help ensure that his job seemed of vital importance to the czar. This guaranteed him a solid berth in Paris that was lucrative both in salary and prestige [and] in opportunities for corrupt under - the - radar dealings with a French government doing heavy business with Russia."

By personally winning the good will and cooperation of the services of host countries, Rachkovsky indirectly assisted his agents and crowned their efforts. For instance, when a penetration agent in Geneva had supplied the essential information about a gathering of terrorists there and external agents had located by surveillance their clandestine printshop and weapons store, Rachkovsky could call on Swiss security units to help destroy the underground and arrest the ringleaders. This happened in 1887; it was repeated in 1888, then again and again in other countries. His powers of persuasion were sufficient to recruit Lev Tikhomirov, one of the leading terrorists, when he had been softened by contrived exposure, and get him to write an anti - revolutionary book.

Rachkovsky's political action operations, often highly successful, were exclusively his personal effort. He devised some plans for using others, but in every major instance he was the sole operator. He befriended a Danish journalist, Jules Hansen, during his first visit to Paris in 1884. Besides being one of the bright lights of his profession, Hansen was a counselor in the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a friend of Minister Delcassé. He became the principal channel for promoting a friendly press for Russia in western Europe, and he made contacts for Rachkovsky with leading ministers and politicians, including even President Loubet. On the other hand, Rachkovsky also cultivated important personages in the imperial government and at court. In these activities he was, as revolutionary writers accused him of being, a manipulator behind the scenes preparing the ground for acceptance, both in Paris and at Petersburg, of the Franco - Russian alliance signed in 1893.

Rachkovsky devised and developed access to several other governments beside the French. The files contain copies of dispatches about an audience he had with Pope Leo XIII and a proposed exchange of diplomats between Russia and the Vatican with particular view to the unrest in Catholic Poland. Advisers to the Tsar in Petersburg turned down the proposal, but the idea of combating the insurrectional campaign in Poland by using religious interests clearly illustrates Rachkovsky's high - level concept of political action.

Rachkovsky's major provocation operation was primarily in support of political action. In 1890 agent Landesen, having promoted among the revolutionaries in Paris an elaborate plot to kill the Tsar, arranged that after one underground meeting a large number of the terrorists would each have on their persons their weapons and written notes on the parts they were to play. The French police, tipped off through cutouts by Rachkovsky, arrested the entire group, and that summer they were tried and sentenced, Landesen in absentia. Rachkovsky thus scored a victory not only over the enemies of the state but against those in Saint Petersburg who had opposed the Franco - Russian alliance on the grounds that France was too soft on subversives. The stern police and court action proved to Petersburg that France too had a strong government capable of dealing with internal enemies.

Rachkovsky may have also played a role in amplifying the carnage of World War I: "Rachkovsky’s bosses in Russia and his hosts in Paris both feared the radicals, allowing the Russian agent to tighten the ties between the two nations. He succeeded so well that [historian Alex] Butterworth argues he was partly to blame for the Russo - French alliance that helped make World War I such a bloody mess."

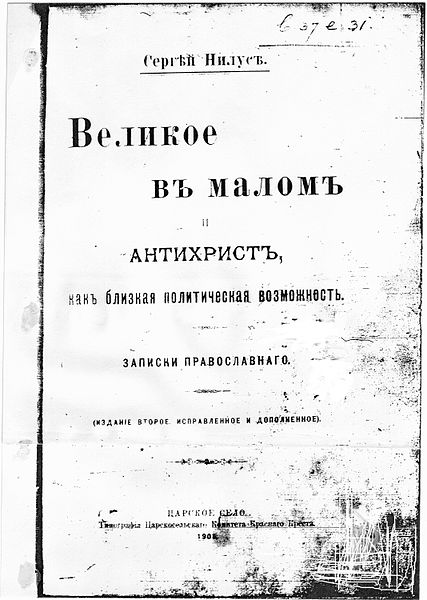

These faction fights provide the backdrop to the infamous fraud The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Many authors maintain that it was Rachkovsky's agent in Paris, Matvei Golovinski, who in the early 1900s authored the first edition. The text presented the impending Russian Revolution of 1905 as a part of a powerful global Jewish conspiracy and fomented anti - Semitism to deflect public attention from Russia's growing social problems. Another Rachkovsky agent, Yuliana Glinka, is often cited as the person who brought the forgery from France to Russia.

After the Revolution of 1905, martial law was introduced in Saint Petersburg. Rachkovsky was brought back to head the entire Okhrana, first as MVD Special Commissioner and then as the Deputy Director of Police.

Rachkovsky had the reputation of being an unrivaled master of

intrigues and provocation. In 1902 he faked a letter by the leader of

the Russian social democrats Georgy Plekhanov

that accused Narodnaya Volya leaders of cooperation with the British

Intelligence Service. This allowed the police to exploit mutual distrust

and recriminations between the factions.

Matvei Vasilyevich Golovinski (alternatively Mathieu; Russian: Матвей Васильевич Головинский; 1865 – 1920) was a Russian - French writer, journalist and political activist. Critics studying the Protocols of the Elders of Zion have argued that he was the author of the work. This claim is reinforced by the writings of modern Russian historian Mikhail Lepekhine, who in 1999 studied previously closed French archives stored in Moscow containing information supporting Golovinski's authorship. Back in the mid 1930s, Russian testimony in the Berne Trial had linked the head of Russian security service in Paris, Pyotr Rachkovsky, to the creation of the Protocols.

Matvei Golovinski was born into an aristocratic family in the village of Ivashevka (Ивашевка), Simbirsk guberniya. His father, Vasili Golovinski (Василий Головинский) was a friend of Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Both were members of the Petrashevsky Circle, sentenced to capital punishment as conspirators and both were pardoned later. Vasili Golovinski died in 1875 and Matvei Golovinski was reared by his mother and the French nanny.

While studying jurisprudence, Golovinski joined the anti - Semitic counter - revolutionary group Holy Brotherhood ("Святое Братство"). Upon graduation, he worked for the Okhrana, secretly arranging pro-government coverage in the press. Golovinski's career almost collapsed and he had to leave the country after his activities were publicly exposed by Maxim Gorky. In France, he wrote and published articles on assignments of the Chief of Russian secret service in Paris, Pyotr Rachkovsky.

After the October Revolution of 1917, Golovinsky switched sides and worked for the Bolsheviks until his death in 1920.

On November 19, 1999, Patrick Bishop reported from Paris:

Research by a leading Russian historian, Mikhail Lepekhine, in recently opened archives has found the forgery to be the work of Mathieu Golovinski, opportunistic scion of an aristocratic but rebellious family that drifted into a life of espionage and propaganda work. After working for the czarist secret service, he later changed sides and joined the Bolsheviks. Mr. Lepekhine’s findings, published in the French magazine L'Express, would appear to clear up the last remaining mystery surrounding the Protocols.

In his 2001 book The Question of the Authorship of "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion", a Ukrainian scholar Vadim Skuratovsky offers a scrupulous and extensive literary, historical and linguistic analysis of the original Russian language text of the Protocols. Skuratovsky provides evidence that Charles Joly, a son of Maurice Joly (on whose writings the Protocols are based), visited Saint Petersburg in 1902 and that Golovinsky and Charles Joly worked together at Le Figaro in Paris. Skuratovsky also traces the influences of Dostoyevsky's prose (in particular, The Grand Inquisitor and The Possessed) on Golovinsky's writings, including The Protocols.

In his book The Non - Existent Manuscript. A Study of the Protocols of the Sages of Zion, Italian researcher Cesare De Michelis writes that the hypothesis of Golovinski authorship was based on statement by Princess Catherine Radziwill, who claimed that she had seen a manuscript of the Protocols written by Golovinsky, Rachkovsky and Manusevich in 1905, but in 1905 Golovinsky and Rachkovsky had already left Paris and moved to Saint Petersburg. Princess Radziwill was known to be an unreliable source.

Golovinski had been linked to the work before; the German writer Konrad Heiden identified him as an author of the Protocols in 1944.