<Back to Index>

- Painter and Inventor Antoine Hércules Romuald Florence, 1804

- Artist and Physicist Louis - Jacques - Mandé Daguerre, 1787

PAGE SPONSOR

Antoine Hercule Romuald Florence (1804 – March 27, 1879) was a French - Brazilian painter and inventor, known as the sole inventor of photography in Brazil, three years before Daguerre (but six years after Nicéphore Niépce), using the matrix negative / positive, still in use. According to Kossoy, who examined Florence's notes, he referred to his process, in French, as photographie in 1834, at least four years before John Herschel coined the English word photography.

Hercules Florence was born on February 29, 1804 in Nice, France, the son of Arnaud Florence (1749 – 1807), a tax collector, and Augustine de Vignolis, a minor noblewoman. As a child he manifested interest for drawing and the sciences, as well as for the voyages of the great explorers to the New World and already as a 14 year old boy he worked as a calligrapher and draftsman in Monaco, where his parents had been living since 1807.

After a period of wandering and working on board of warships and merchant ships, Hércules Florence set sail to Brazil as a crew member of the French warship Marie Thérèze, arriving in the port of Rio de Janeiro on May 1, 1824, two years after the declaration of independence from Portugal. He was already an accomplished draftsman and painter with considerable talent and many scientific interests, particularly in the natural sciences and ethnography. Soon after his arrival, he got a job in a women's fashion store and then as a lithographer in a bookstore and printing shop, owned by his compatriot Pierre Plancher.

Florence's life changed dramatically when he decided to respond to a newspaper advertisement put by Baron von Langsdorff (1773 – 1852), the consul general of the Russian Empire in Brazil, a German born physician and naturalist who was organizing on behalf of the Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences a scientific expedition to the Amazon. He was hired as an illustrator and topographic draftsman, together with German painter Johann Moritz Rugendas (1802 – 58) and the young French illustrator Adrien Taunay (1803 – 28). In the year of 1825 they traveled by sea from Rio to the village of Santos. While they waited for the set day of departure to the Amazon, Florence and other members of the scientific expedition spent their days exploring the coastal lowland areas, such as Cubatão, and the high rising plateau beyond the imposing Serra do Mar: they visited the towns of São Paulo, Juqueri, Jundiai, Itu and Campinas. In Porto Feliz, the town by the Tietê River, located 80 km northwest of São Paulo, where the departure would take place, Florence was hosted for a while by surgeon and politician Francisco Álvares Machado e Vasconcellos (1791 – 1846).

From 1826 to 1829 he accompanied Langsdorff's expeditionary party through its many vicissitudes and disease, and was the only artist to arrive at Belém (Pará) and return unscathed to Rio.

His vivid and detailed illustrations, drawings and watercolors picturing the local flora and fauna, the landscapes, and, particularly, the many inhabitants and Indians met during the voyage; were very important for the documentation of Langsdorff's voyage, as well as for his subsequent career.

Back to Rio, Florence left the manuscript of his diary of the expedition, with 84 pages (written in French) with Félix Taunay (1795 – 1881), the brother of his companion Adrien. The manuscript was translated to Portuguese and published by the son of Félix, the historian Alfredo D´Escragnolle Taunay more than 40 years later, in 1875. In 1849, Florence completed his description of the fabulous adventure, which was published for the first time in 1977, under the title "A Fluvial Voyage from Tietê to Amazon Rivers, through the Brazilian Provinces of São Paulo, Mato Grosso and Grand - Pará (1825 – 1829)".

Soon after the end of the expedition, in 1830, Florence married Maria

Angélica de Vasconcellos, the daughter of his acquaintance and

benefactor Francisco Álvares Machado, and went to live with her

in the

small city of Campinas (then named the village of São Carlos), in

the province of São Paulo. There he became a successful farmer, publisher and owner of the first printer

in the town, and in Campinas he remained for the next 49 years until

his death in 1879. Maria died in 1850; four years later he married

Carolina Krug, a German immigrant born in 1828 in Kassel. Together they

founded in 1863 a school for girls, the Florence College, which was

moved to Jundiai after Hercule's death. He fathered a total of 20 children, being 13 with Maria Angélica and 7 with Carolina.

Soon after settling in Campinas, Hércules Florence began a prolific career as inventor and businessman. During the Langsdorff expedition, he had developed a new system of using musical notation to record the songs of birds and vocalizations of other animals, which he named "zoophonia". Then, in 1830, when he was searching for a simplified way of printing his more than 200 illustrations performed during the Langsdorff Expedition, other than using expensive and time consuming engravings on wood and metal (xylography and lithography), he invented a new process, similar to the mimeograph, which he named "polygraphia", and began using this commercially in his printing office. As his technique evolved, he was able to combine colors, and to produce uncounterfeitable bank notes.

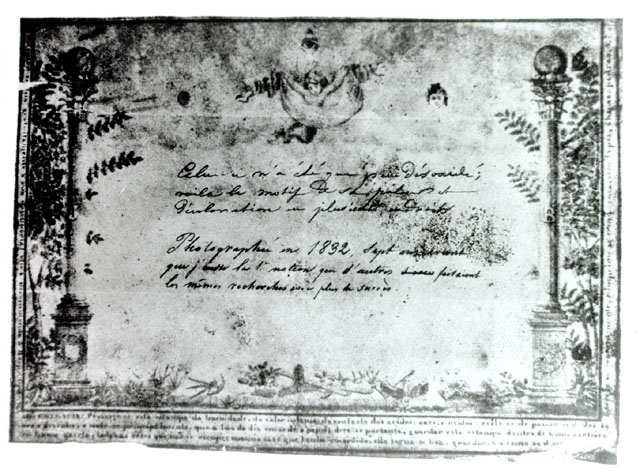

In 1832, with the help of a pharmacist friend, Joaquim Correa de Mello, he began to study ways of permanently fixing camera obscura images, which he named "photographia". In 1833, they settled on silver nitrate on paper, in a process very similar to that developed by Niépce and Daguerre. Unfortunately, partly because he never published the invention adequately, partly because he was an obscure inventor living in a remote and underdeveloped province, Hércules Florence was never recognized internationally as one of the inventors of photography.

A film documentary, featuring Adriana Florence, a grand - grand - granddaughter of Hércules Florence living in Campinas, Brazil, has been made by the Discovery Channel

and retraces part of the Baron von Langsdorff expedition's itinerary.

It also visited the St. Petersburg's Langsdorff museum collections. The

director was Mauricio Dias.

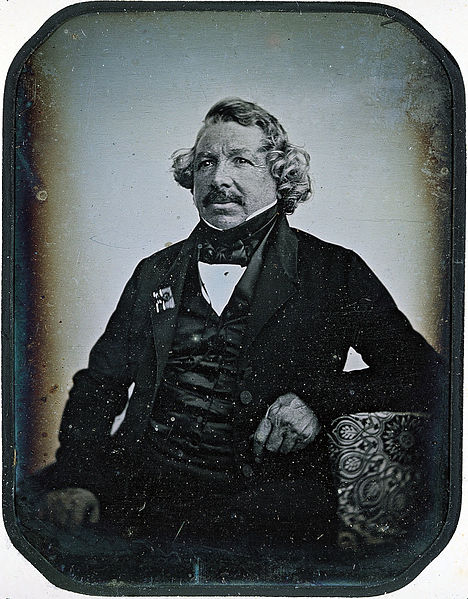

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (18 November 1787 – 10 July 1851) was a French artist and physicist, recognized for his invention of the daguerreotype process of photography.

Daguerre was born in Cormeilles - en - Parisis, Val - d'Oise, France. He apprenticed in architecture, theater design, and panoramic painting with Pierre Prévost, the first French panorama painter. Exceedingly adept at his skill of theatrical illusion, he became a celebrated designer for the theater and later came to invent the Diorama, which opened in Paris in July 1822.

In 1829, Daguerre partnered with Nicéphore Niépce, an inventor who had produced the world's first heliograph in 1822 and the first permanent camera photograph four years later. Niépce died suddenly in 1833, but Daguerre continued experimenting and evolved the process which would subsequently be known as the Daguerreotype. After efforts to interest private investors proved fruitless, Daguerre went public with his invention in 1839. At a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences on 7 January of that year, the invention was announced and described in general terms, but all specific details were withheld. Under assurances of strict confidentiality, Daguerre explained and demonstrated the process only to the Academy's perpetual secretary François Arago, who proved to be an invaluable advocate. Members of the Academy and other select individuals were allowed to examine specimens at Daguerre's studio. The images were enthusiastically praised as nearly miraculous and news of the Daguerreotype quickly spread. Arrangements were made for Daguerre's rights to be acquired by the French Government in exchange for lifetime pensions for himself and Niépce's son Isidore; then, on 19 August 1839, the French Government presented the invention as a gift from France "free to the world" and complete working instructions were published.

Daguerre died on 10 July 1851 of a heart attack in Bry - sur - Marne, 12 km (7 mi) from Paris. A monument marks his grave there.

Daguerre's name is one of the 72 names inscribed on the Eiffel tower.

In 1826, prior to his association with Daguerre, Niépce used a coating of bitumen to make the first permanent camera photograph. The bitumen was hardened where it was exposed to light and the unhardened portion was then removed with a solvent. A camera exposure lasting for hours or days was required. Niépce and Daguerre later refined this process, but unacceptably long exposures were still needed.

After the death of Niépce in 1833, Daguerre concentrated his attention on the light sensitive properties of silver salts, which had previously been demonstrated by Johann Heinrich Schultz and others. For the process which was eventually named the Daguerreotype, he exposed a thin silver - plated copper sheet to the vapor given off by iodine crystals, producing a coating of light sensitive silver iodide on the surface. The plate was then exposed in the camera. Initially, this process, too, required a very long exposure to produce a distinct image, but Daguerre made the crucial discovery that an invisibly faint "latent" image created by a much shorter exposure could be chemically "developed" into a visible image. The latent image on a Daguerreotype plate was developed by subjecting it to the vapor given off by mercury heated to 75° Celsius. The resulting visible image was then "fixed" (made insensitive to further exposure to light) by removing the unaffected silver iodide with concentrated and heated salt water. Later, a solution of the more effective "hypo" (hyposulphite of soda, now known as sodium thiosulfate) was used instead.

The resultant plate produced an exact reproduction of the scene. The image was laterally reversed -- as images in mirrors are -- unless a mirror or inverting prism was used during exposure to flip the image. To be seen optimally, the image had to be lit at a certain angle and viewed so that the smooth parts of its mirror like surface, which represented the darkest parts of the image, reflected something dark or dimly lit. The surface was subject to tarnishing by prolonged exposure to the air and was so soft that it could be marred by the slightest friction, so a Daguerreotype was almost always sealed under glass before being framed (as was commonly done in France) or mounted in a small folding case (as was normal in the UK and US).

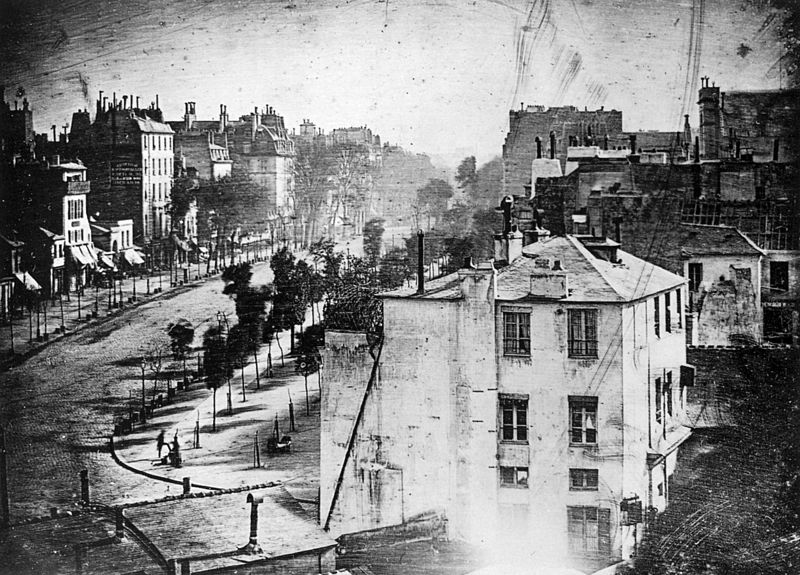

Daguerreotypes were usually portraits; the rarer landscape views and other unusual subjects are now much sought after by collectors and sell for much higher prices than ordinary portraits. At the time of its introduction, the process required exposures lasting ten minutes or more for brightly sunlit subjects, so portraiture was an impractical ordeal. Samuel Morse was astonished to learn that Daguerreotypes of the streets of Paris did not show any people, horses or vehicles, until he realized that due to the long exposure times all moving objects became invisible. Within a few years, exposures had been reduced to as little as a few seconds by the use of additional sensitizing chemicals and "faster" lenses such as Petzval's portrait lens, the first mathematically calculated lens.

The Daguerreotype was the Polaroid film of its day: it produced a unique image which could only be duplicated by using a camera to photograph the original. Despite this drawback, millions of Daguerreotypes were produced. The paper based calotype process, introduced by Henry Fox Talbot in 1841, allowed the production of an unlimited number of copies by simple contact printing, but it had its own shortcomings — the grain of the paper was obtrusively visible in the image and the extremely fine detail of which the Daguerreotype was capable was not possible. The introduction of the wet collodion process in the early 1850s provided the basis for a negative - positive print making process not subject to these limitations, although it, like the Daguerreotype, was initially used to produce one - of - a - kind images — ambrotypes on glass and tintypes on black - lacquered iron sheets — rather than prints on paper. These new types of images were much less expensive than Daguerreotypes and they were easier to view. By 1860 few photographers were still using Daguerre's process.

The same small ornate cases commonly used to house Daguerreotypes

were also used for images produced by the later and very different ambrotype and tintype

processes, and the images originally in them were sometimes later

discarded so that they could be used to display photographic paper

prints. It is now a very common error for any image in such a case to be

described as "a Daguerreotype". A true Daguerreotype is always an image

on a highly polished silver surface, usually under protective glass. If

it is viewed while a brightly lit sheet of white paper is held so as to

be seen reflected in its mirror - like metal surface, the Daguerreotype

image will appear as a relatively faint negative — its

dark and light areas reversed — instead of a normal positive. Other types

of photographic images are almost never on polished metal and do not

exhibit this peculiar characteristic of appearing positive or negative

depending on the lighting and reflections.

Unbeknownst to either inventor, Daguerre's developmental work in the mid 1830s coincided with photographic experiments being conducted by Henry Fox Talbot in England. Talbot had succeeded in producing a "sensitive paper" impregnated with silver chloride and capturing small camera images on it in the summer of 1835. At least one of those images still survives. Talbot was unaware that Daguerre's late partner Niépce had obtained similar small camera images on sliver chloride coated paper nearly twenty years earlier. Niépce could find no way to keep them from darkening all over when exposed to light for viewing and had therefore turned away from silver salts to experiment with other substances such as bitumen. Talbot, a gifted amateur chemist, was able to chemically stabilize his images sufficiently to withstand subsequent inspection in daylight with only a very limited degree of discoloration.

When the first reports of the French Academy of Sciences announcement of Daguerre's invention reached Talbot, with no details about the exact nature of the images or the process itself, he assumed that methods similar to his own must have been used and promptly wrote an open letter to the Academy claiming priority of invention. Although it soon became apparent that Daguerre's process was very unlike his own, Talbot had been stimulated to resume his long discontinued photographic experiments, which eventually resulted in the calotype process, introduced in 1841. Like a sensitized Daguerreotype plate, but unlike Talbot's earlier "sensitive paper", better known as "salted paper", the calotype paper had to be exposed in the camera only long enough to produce a very faint or completely invisible image which was then chemically developed to full visibility. The negative image that resulted was made insensitive to light by treatment with "hypo", dried, then used to make one or more positive prints on salted paper by contact printing in sunlight.

Daguerre's agent in England applied for a British patent just days before France declared the invention "free to the world". Great Britain was thereby uniquely denied France's free gift and became the only country where the payment of license fees was required. This had the effect of inhibiting the spread of the process there, to the eventual advantage of competing processes which were subsequently introduced. Antoine Claudet was one of the few people legally licensed to make Daguerreotypes in Britain. Daguerre's pension was relatively modest — barely enough to support a middle class existence — and apparently this British "irregularity" was allowed to pass without adverse consequences or much comment outside of the UK.

By contrast, resentment and negative comments certainly resulted when

the independently wealthy Talbot, who had spent a considerable amount

of money in developing his calotype process (about £5,000, equivalent to £378,000 as of 2012),

did not make a similar general gift of it to mankind, or at least to

his own countrymen, but opted to emulate Daguerre's UK policy and

require the purchase of licenses for its use. This inhibited the

widespread adoption of the calotype process as an alternative to the

Daguerreotype in the UK. Eventually, Talbot relented and required

licenses only from professional photographers using the process for

portraiture. Talbot also gained a reputation for litigiousness, suing

several subsequent inventors whose processes he believed to infringe the

broad claims made in some of his own British patents.