<Back to Index>

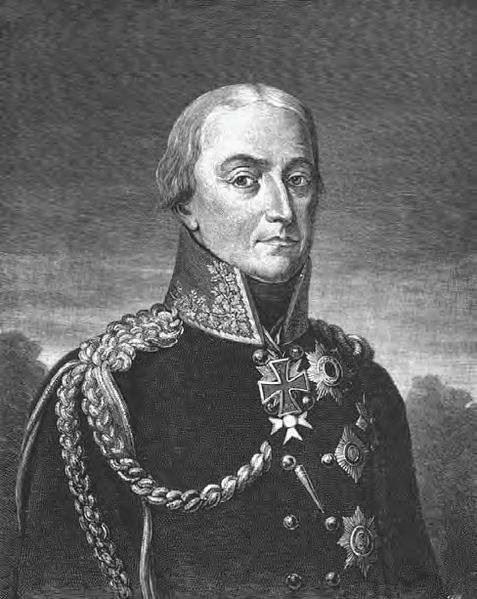

- Commander of the IV Corps Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Bülow, 1755

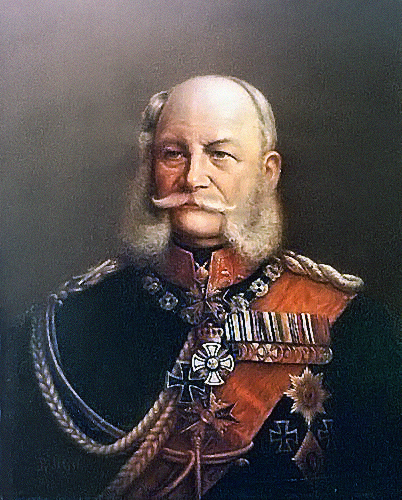

- King of Prussia and Emperor of Germany Wilhelm I, 1797

PAGE SPONSOR

Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Bülow, Graf von Dennewitz (February 16, 1755 – February 25, 1816) was a Prussian general of the Napoleonic Wars.

Bülow was born in Falkenberg (Wische) in the Altmark and was the elder brother of Freiherr Dietrich Heinrich von Bülow. He received an excellent education, and entered the Prussian army in 1768, becoming ensign in 1772, and second lieutenant in 1775. He took part in the Potato War of 1778, and subsequently devoted himself to the study of his profession and of the sciences and arts.

Throughout his life Bülow was devoted to music, his great musical

ability bringing him to the notice of King Frederick William II of

Prussia, and ca. 1790 he was conspicuous in the most fashionable circles

of Berlin. He did not, however, neglect his military studies, and in

1792 he was made military instructor to the young Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia,

becoming at the same time full captain. He took part in the campaigns

of 1792 - 94 on the Rhine, and received for signal courage during the

siege of Mainz the order Pour le Mérite and promotion to the rank of

major.

After this Bülow went to garrison duty at Soldau. In 1802 he married the daughter of Colonel von Auer, and in the following year he became lieutenant colonel, remaining at Soldau with his corps. The vagaries and misfortunes of his brother Dietrich affected his happiness as well as his fortune. The loss of two of his children was followed in 1806 by the death of his wife, and a further source of disappointment was the exclusion of his regiment from the field army sent against Napoleon in 1806. The disasters of the campaign aroused his energies. He did excellent service under Anton Wilhelm von L'Estocq's command in the latter part of the war, was wounded in action, and finally designated for a brigade command in Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher's force.

In 1808 Bülow married the sister of his first wife, a girl of eighteen. He was made a major general in the same year, and henceforward he devoted himself wholly to the regeneration of Prussia. The intensity of his patriotism threw him into conflict even with Blücher and led to his temporary retirement; in 1811, however, he was again employed.

In the critical days preceding the War of Liberation, Bülow kept his troops in hand without committing himself to any irrevocable step until the decision was made. On 14 March 1813 he was made a lieutenant general. He fought against Oudinot in defense of Berlin, and in the summer came under the command of Bernadotte, crown prince of Sweden. At the head of an army corps Bülow distinguished himself greatly in the Battle of Grossbeeren, a victory which was attributed almost entirely to his leadership. A little later he won the great victory at the Battle of Dennewitz, which for the second time checked Napoleon's advance on Berlin. This inspired the greatest enthusiasm in Prussia, as being won by mainly Prussian forces, and rendered Bülow's popularity almost equal to that of Blücher. Bülow's corps played a conspicuous part in the final overthrow of Napoleon at Leipzig, and he was then entrusted with the task of evicting the French from Holland and Belgium. In an almost uniformly successful campaign he won a signal victory at Hoogstraten although he was fortunate to be supported, often very significantly, by the British General Thomas Graham, second in command to Lord Wellington. In the campaign of 1814 he invaded France from the north - west, joined Blücher, and took part in the brilliant victory of Laon in March. He was made general of infantry and received the title of Count Bülow von Dennewitz. He also took part in the Allied sovereigns' visit to England in June 1814.

In the short peace of 1814 - 1815 Bülow was at Königsberg as commander -

in - chief in Prussia proper. He was soon called to the field again,

and in the Waterloo campaign commanded the IV Corps of Blücher's army.

He was not present at Ligny, but his corps headed the flank attack upon

Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo,

and bore the heaviest part in the fighting of the Prussian troops

around Plancenoit. He took part in the invasion of France, but died

suddenly on 25 February 1816, a month after his return to the Königsberg

command.

William I, also known as Wilhelm I (full name: William Frederick Louis, German: Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig) (22 March 1797 – 9 March 1888), of the House of Hohenzollern was the King of Prussia (2 January 1861 – 9 March 1888) and the first German Emperor (18 January 1871 – 9 March 1888).

Under the leadership of William and his Chancellor Otto von Bismarck,

Prussia achieved the unification of Germany and the establishment of

the German Empire.

The future king and emperor was born William Frederick Louis of Prussia (Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig von Preußen) in Berlin. As the second son of King Frederick William III and Louise of Mecklenburg - Strelitz, William was not expected to ascend to the throne and hence received little education.

William served in the army from 1814 onward, fought against Napoleon I of France during the Napoleonic Wars, and was reportedly a very brave soldier. He fought under Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher at the Battles of Ligny and Waterloo. He also became an excellent diplomat by engaging in diplomatic missions after 1815.

During the Revolutions of 1848, William successfully crushed a revolt that was aimed at his elder brother King Frederick William IV. The use of cannons made him unpopular at the time and earned him the nickname Kartätschenprinz (Prince of Grapeshot).

In 1854, the prince was raised to the rank of a field marshal and made governor of the federal fortress of Mainz. In 1857 Frederick William IV suffered a stroke and became mentally disabled for the rest of his life. In January 1858, William became Prince Regent for his brother.

On 2 January 1861 Frederick William died and William ascended the throne as William I of Prussia. He inherited a conflict between Frederick William and the liberal parliament. He was considered a politically neutral person as he intervened less in politics than his brother. William nevertheless found a conservative solution for the conflict: he appointed Otto von Bismarck to the office of Prime Minister. According to the Prussian constitution, the Prime Minister was responsible solely to the king, not to parliament. Bismarck liked to see his working relationship with William as that of a vassal to his feudal superior. Nonetheless, it was Bismarck who effectively directed the politics, domestic as well as foreign; on several occasions he gained Wilhelm's assent by threatening to resign.

During the Franco - Prussian War, on 18 January 1871 in Versailles Palace, William was proclaimed German Emperor.

The title "German Emperor" was carefully chosen by Bismarck after

discussion until (and after) the day of the proclamation. William

accepted this title grudgingly as he would have preferred "Emperor of Germany"

which, however, was unacceptable to the federated monarchs, and would

also have signaled a claim to lands outside his realm (Austria,

Switzerland, Luxembourg etc.). The title "Emperor of the Germans", as

proposed in 1848, was ruled out as he considered himself chosen "by the grace of God", not by the people as in a democratic republic.

By this ceremony, the North German Confederation (1867 – 1871) was transformed into the German Empire ("Kaiserreich", 1871 – 1918). This Empire was a federal state; the emperor was head of state and president (primus inter pares – first among equals) of the federated monarchs (the kings of Bavaria, Württemberg, Saxony, the grand dukes of Baden, Mecklenburg, Hesse, as well as other principalities, duchies and the senates of the free cities of Hamburg, Lübeck and Bremen).

In his memoirs, Bismarck describes William as an old fashioned, courteous, infallibly polite gentleman and a genuine Prussian officer, whose good common sense was occasionally undermined by "female influences".

Kaiser Wilhelm I arbitrated a boundary dispute between Great Britain

and the United States, deciding in favor of the U.S. and placing the San

Juan Islands of Washington State within U.S. national territory, thus

ending the 12 year Pig War between British and U.S. forces on San Juan Island, on October 21, 1872.

On 11 May 1878, a plumber named Emil Max Hödel failed in an assassination attempt on William in Berlin. Hödel used a revolver to shoot at the Emperor, while the 81 year old and his daughter, Princess Louise of Prussia, paraded in their carriage. When the bullet missed, Hödel ran across the street and fired another round which also missed. In the commotion one of the individuals who tried to apprehend Hödel suffered severe internal injuries and died two days later.

The State convicted Hödel after a photographer who took the radical’s picture days before the assassination attempt testified that after he took the picture Hödel said it would sell thousands once a certain piece of information [was] hashed through the world. Hödel was beheaded on 16 August 1878.

A second attempt to assassinate Wilhelm I was made on 2 June 1878 by

Karl Nobiling. As the Emperor drove past in an open carriage, the

assassin fired a shotgun at him from the window of a house off the

"Unter den Linden".

William was wounded and was rushed back to the palace and Nobiling shot

himself in an attempt to commit suicide. While William survived this

attack, the assassin died from his self inflicted wound three months

later.

Despite the fact that Hödel had been expelled from the Social Democratic Party, his actions were used as a pretext to ban the party through the Anti - Socialist Law in October 1878. To do this, Bismarck partnered with Ludwig Bamberger, a Liberal, who had written on the subject of Socialism, “If I don’t want any chickens, then I must smash the eggs.” No one in the Social Democratic Party even knew of Karl Nobiling, but that is not to say that he was not politically motivated. Unfortunately, the aspiring assassin mortally wounded himself before he could be interrogated. The gunshot to the head did not immediately kill him, but he finally succumbed to his injuries in September 1878.

These attempts became the pretext for the institution of the Anti - Socialist Law, which was introduced by Bismarck’s government with the support of a majority in the Reichstag on 18 October 1878, for the purpose of fighting the socialist and working class movement. The laws deprived the Social Democratic Party of Germany of its legal status; they prohibited all organizations, workers’ mass organizations and the socialist and workers’ press, decreed confiscation of socialist literature, and subjected Social Democrats to reprisals.

The laws were extended every 2–3 years. Despite this policy of reprisals the Social Democratic Party increased its influence among the masses. Under pressure of the mass working class movement the laws were repealed on 1 October 1890.