<Back to Index>

- Philosopher and Politician Confucius (Kongzi), 551 B.C.

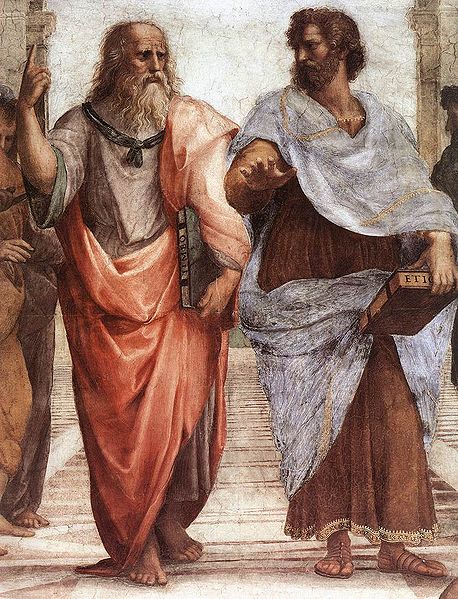

- Philosopher Plato (Πλάτων), 424 B.C.

PAGE SPONSOR

Confucius (Chinese: 孔子, pin. Kǒngzǐ, Wade K'ung-tzu, lit. "Master Kong"; 551 – 479 BC) was a Chinese politician, teacher, editor, and social philosopher of the Spring and Autumn Period of Chinese history.

The philosophy of Confucius emphasized personal and governmental morality, correctness of social relationships, justice and sincerity. His followers competed successfully with many other schools during the Hundred Schools of Thought era only to be suppressed in favor of the Legalists during the Qin Dynasty. Following the victory of Han over Chu after the collapse of Qin, Confucius's thoughts received official sanction and were further developed into a system known as Confucianism.

Confucius is traditionally credited with having authored or edited many of the Chinese classic texts including all of the Five Classics, but modern scholars are cautious of attributing specific assertions to Confucius himself. Aphorisms concerning his teachings were compiled in the Analects, but only many years after his death.

Confucius's principles had a basis in common Chinese tradition and

belief. He championed strong family loyalty, ancestor worship, respect

of elders by their children (and in traditional interpretations

of husbands by their wives), and family as a basis for ideal

government. He expressed the well known principle "Do not do to others

what you do not want done to yourself", an earlier version of the Golden

Rule.

Confucius was said to have been born in 551 BC at the beginning of the Hundred Schools of Thought. Confucius was born in or near the city of Qufu in the Zhou state of Lu in modern Shandong. Early accounts say he was born into a poor but noble warrior family that had fallen on hard times. His father Kong He (孔纥, Kǒng Hé; also known as 叔梁紇, Shūliáng Hé) had served in two battles and owned a minor fiefdom. Sima Qian's 1st century BC Records of the Grand Historian stated that Confucius was the result of an "illicit union" (野合, yehe) between Kong He and Yan Zheng. Later legends said that Zheng first abandoned her ugly baby in a cave on Mount Ni, but was convinced to recover him after he was cared for by a lion and an eagle.

Kong He died when Confucius was only three years old and the boy was brought up in poverty by his mother. As a child, Confucius was said to have enjoyed putting ritual vases on the sacrifice table. He married a young girl named Qi Guan (亓官) at 19 and she gave birth to their first child, Kong Li (孔鯉), the next year.

Confucius's social ascendancy linked him to the growing class of shì (士), a class intermediate between the new nobility and the common people and comprised of men seeking employment on the basis of their talents and skills. Confucius is reported to have worked as a shepherd, cowherd, clerk and a book keeper. His mother died when Confucius was 23, and he then observed the ritual three years of mourning.

At the age of 53, Confucius rose to the position of Justice Minister (大司寇) in Lu. In Sima Qian's account, the neighboring state of Qi was worried that Lu was becoming too powerful. Qi decided to sabotage Lu's reforms by sending 100 good horses and 80 beautiful dancing girls to the Duke of Lu. The Duke indulged himself in pleasure and did not attend to official duties for three days. Confucius was deeply disappointed and resolved to leave Lu and seek better opportunities, yet to leave at once would expose the misbehavior of the Duke and therefore bring public humiliation to the ruler Confucius was serving. Confucius therefore waited for the Duke to make a lesser mistake. Soon after, the Duke neglected to send to Confucius a portion of the sacrificial meat that was his due according to custom, and Confucius seized upon this pretext to leave both his post and the state of Lu.

After Confucius's resignation, he began a long journey or set of journeys around the small kingdoms of northeast and central China, traditionally including the states of Wei, Song, Chen, and Cai. At the courts of these states, he expounded his political beliefs but did not see them implemented.

According to the Zuo Zhuan, Confucius returned home when he was 68. The Analects depict him spending his last years teaching 72 or 77 disciples and transmitting the old wisdom via a set of texts called the Five Classics.

Confucius's real name was Kong Qiu (孔丘, Kǒng Qiū) but, owing to the Chinese naming taboo, he was known to his peers by his courtesy name Zhongni (仲尼, Zhòngní) instead. Within the Analects, he is principally referred to simply as "The Master" (子, Zǐ).

Of course, the Chinese at the time was very different. One reconstruction of his personal name is Kʰˤoŋʔ Kʷʰə; his courtesy name may have sounded like Truŋsnˤərs.

In AD 1 (which was also the first year of the Yuanshi Era of the Han Dynasty), Confucius was given his first posthumous name: the "Laudably Declarable Lord Ni" (褒成宣尼公, Bāochéngxuān Ní Gōng). In 1530 (the ninth year of the Jiajing Era of the Ming Dynasty), he was declared the "Extremely Sage Departed Teacher" (至圣先师, Zhìshèngxiānshī) and he is also known separately as the "Great Sage" (至圣) and "First Teacher" (先师), as well as the "Model Teacher for Ten Thousand Ages" (万世师表, Wànshì Shībiǎo)

In modern Chinese, he is most often called "Master Kong" (孔子, Kǒngzǐ) and a variant of this – Kǒng Fūzǐ (孔夫子) – was Latinized by the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci as "Confucius". In the Wade – Giles system of romanization, the same name is rendered as K'ung Fu-tzu or Kung Fu-tze.

Although Confucianism is often followed in a religious manner by the Chinese, arguments continue over whether it is a religion. Confucianism discusses elements of the afterlife and views concerning Heaven, but it is relatively unconcerned with some spiritual matters often considered essential to religious thought, such as the nature of the soul(s).

In the Analects, Confucius presents himself as a "transmitter who invented nothing". He puts the greatest emphasis on the importance of study, and it is the Chinese character for study (学) that opens the text. Far from trying to build a systematic or formalist theory, he wanted his disciples to master and internalize the old classics, so that their deep thought and thorough study would allow them to relate the moral problems of the present to past political events (as recorded in the Annals) or the past expressions of commoners' feelings and noblemen's reflections (as in the poems of the Book of Odes.

One of the deepest teachings of Confucius may have been the superiority of personal exemplification over explicit rules of behavior. His moral teachings emphasized self cultivation, emulation of moral exemplars, and the attainment of skilled judgment rather than knowledge of rules. Confucian ethics may be considered a type of virtue ethics. His teachings rarely rely on reasoned argument and ethical ideals and methods are conveyed more indirectly, through allusion, innuendo and even tautology. His teachings require examination and context in order to be understood. A good example is found in this famous anecdote:

-

- 廄焚。子退朝,曰:“傷人乎?” 不問馬。

- When the stables were burned down, on returning from court Confucius said, "Was anyone hurt?" He did not ask about the horses.

-

-

-

-

- Analects X.11 (tr. Waley), 10-13 (tr. Legge), or X-17 (tr. Lau)

-

-

-

-

By not asking about the horses, Confucius demonstrates that the sage values human beings over property; readers are led to reflect on whether their response would follow Confucius's and to pursue self improvement if it would not have. Confucius, as an exemplar of human excellence, serves as the ultimate model, rather than a deity or a universally true set of abstract principles. For these reasons, according to many commentators, Confucius's teachings may be considered a Chinese example of humanism.

One of his most famous teachings was a variant of the Golden Rule sometimes called the "Silver Rule" owing to its negative form:

-

- 己所不欲,勿施於人。

- "What you do not wish for yourself, do not do to others."

-

- 子貢問曰:“有一言而可以終身行之者乎”?子曰:“其恕乎!己所不欲、勿施於人。”

- Zi Gong [a disciple] asked: "Is there any one word that could guide a person throughout life?"

The Master replied: "How about 'reciprocity'! Never impose on others what you would not choose for yourself."-

-

-

-

- Analects XV.24, tr. David Hinton

-

-

-

-

Although the above rules are in some way universal, Confucius would be called an ethical particularist because of how he interprets these rules. Confucius believes that there is a duty to family and friends before there is a duty to community. Therefore, in different situations Confucius would counsel a person to do different things.

Often overlooked in Confucian ethics are the virtues to the self:

sincerity and the cultivation of knowledge. Virtuous action towards

others begins with virtuous and sincere thought, which begins with

knowledge. A virtuous disposition without knowledge is susceptible to

corruption and virtuous action without sincerity is not true

righteousness. Cultivating knowledge and sincerity is also important for

one's own sake; the superior person loves learning for the sake of

learning and righteousness for the sake of righteousness.

The Confucian theory of ethics as exemplified in Lǐ (禮) is based on three important conceptual aspects of life: ceremonies associated with sacrifice to ancestors and deities of various types, social and political institutions, and the etiquette of daily behavior. It was believed by some that lǐ originated from the heavens, but Confucius stressed the development of lǐ through the actions of sage leaders in human history. His discussions of lǐ seem to redefine the term to refer to all actions committed by a person to build the ideal society, rather than those simply conforming with canonical standards of ceremony.

In the early Confucian tradition, lǐ was doing the proper thing at the proper time, balancing between maintaining existing norms to perpetuate an ethical social fabric, and violating them in order to accomplish ethical good. Training in the lǐ of past sages cultivates in people virtues that include ethical judgment about when lǐ must be adapted in light of situational contexts.

In Confucianism, the concept of li is closely related to yì (義), which is based upon the idea of reciprocity. Yì can be translated as righteousness, though it may simply mean what is ethically best to do in a certain context. The term contrasts with action done out of self - interest. While pursuing one's own self - interest is not necessarily bad, one would be a better, more righteous person if one's life was based upon following a path designed to enhance the greater good. Thus an outcome of yì is doing the right thing for the right reason.

Just as action according to Lǐ should be adapted to conform to the aspiration of adhering to yì, so yì is linked to the core value of rén (仁). Rén consists of 5 basic virtues: seriousness, generosity, sincerity, diligence and kindness. Rén

is the virtue of perfectly fulfilling one's responsibilities toward

others, most often translated as "benevolence" or "humaneness";

translator Arthur Waley calls it "Goodness" (with a capital G),

and other translations that have been put forth include

"authoritativeness" and "selflessness." Confucius's moral system was

based upon empathy and understanding others, rather than divinely ordained rules. To develop one's spontaneous responses of rén so that these could guide action intuitively was even better than living by the rules of yì.

Confucius asserts that virtue is a means between extremes. For example,

the properly generous person gives the right amount — not too much and

not too little.

Confucius' political thought is based upon his ethical thought. He argues that the best government is one that rules through "rites" (lǐ) and people's natural morality, rather than by using bribery and coercion. He explained that this is one of the most important analects: "If the people be led by laws, and uniformity sought to be given them by punishments, they will try to avoid the punishment, but have no sense of shame. If they be led by virtue, and uniformity sought to be given them by the rules of propriety, they will have the sense of the shame, and moreover will become good." (Translated by James Legge) in the Great Learning (大學). This "sense of shame" is an internalization of duty, where the punishment precedes the evil action, instead of following it in the form of laws as in Legalism.

Confucius looked nostalgically upon earlier days, and urged the Chinese, particularly those with political power, to model themselves on earlier examples. In times of division, chaos and endless wars between feudal states, he wanted to restore the Mandate of Heaven (天命) that could unify the "world" (天下, "all under Heaven") and bestow peace and prosperity on the people. Because his vision of personal and social perfections was framed as a revival of the ordered society of earlier times, Confucius is often considered a great proponent of conservatism, but a closer look at what he proposes often shows that he used (and perhaps twisted) past institutions and rites to push a new political agenda of his own: a revival of a unified royal state, whose rulers would succeed to power on the basis of their moral merits instead of lineage. These would be rulers devoted to their people, striving for personal and social perfection, and such a ruler would spread his own virtues to the people instead of imposing proper behavior with laws and rules.

While he supported the idea of government by an all - powerful sage,

ruling as an Emperor, his ideas contained a number of elements to limit

the power of rulers. He argued for according language with truth, and

honesty was of paramount importance. Even in facial expression,

truth must always be represented. Confucius believed that if a ruler

were to lead correctly, by action, that orders would be deemed

unnecessary in that others will follow the proper actions of their

ruler. In discussing the relationship between a king and his subject (or

a father and his son), he underlined the need to give due respect to

superiors. This demanded that the inferior must give advice to his

superior if the superior was considered to be taking the course of

action that was wrong. Confucius believed in ruling by example, if you

lead correctly, orders are unnecessary and useless.

Confucius's teachings were later turned into an elaborate set of rules and practices by his numerous disciples and followers, who organized his teachings into the Analects. Confucius' disciples and his only grandson, Zisi, continued his philosophical school after his death. These efforts spread Confucian ideals to students who then became officials in many of the royal courts in China, thereby giving Confucianism the first wide scale test of its dogma.

Two of Confucius's most famous later followers emphasized radically different aspects of his teachings. In the centuries after his death, Mencius (孟子) and Xun Zi (荀子) both composed important teachings elaborating in different ways on the fundamental ideas associated with Confucius. Mencius (4th century BC) articulated the innate goodness in human beings as a source of the ethical intuitions that guide people towards rén, yì, and lǐ, while Xun Zi (3rd century BC) underscored the realistic and materialistic aspects of Confucian thought, stressing that morality was inculcated in society through tradition and in individuals through training. In time, their writings, together with the Analects and other core texts came to constitute the philosophical corpus of Confucianism.

This realignment in Confucian thought was parallel to the development of Legalism, which saw filial piety as self interest and not a useful tool for a ruler to create an effective state. A disagreement between these two political philosophies came to a head in 223 BC when the Qin state conquered all of China. Li Ssu, Prime Minister of the Qin Dynasty convinced Qin Shi Huang to abandon the Confucians' recommendation of awarding fiefs akin to the Zhou Dynasty before them which he saw as counter to the Legalist idea of centralizing the state around the ruler. When the Confucian advisers pressed their point, Li Ssu had many Confucian scholars killed and their books burned — considered a huge blow to the philosophy and Chinese scholarship.

Under the succeeding Han Dynasty and Tang Dynasty, Confucian ideas gained even more widespread prominence. Under Wudi, the works of Confucius were made the official imperial philosophy and required reading for civil service examinations in 140 BC which was continued nearly unbroken until the end of the 19th Century. As Moism lost support by the time of the Han, the main philosophical contenders were Legalism, which Confucian thought somewhat absorbed, the teachings of Lao-tzu, whose focus on more mystic ideas kept it from direct conflict with Confucianism, and the new Buddhist religion, which gained acceptance during the Southern and Northern Dynasties era. Both Confucian ideas and Confucian trained officials were relied upon in the Ming Dynasty and even the Yuan Dynasty, although Kublai Khan distrusted handing over provincial control.

During the Song Dynasty, the scholar Zhu Xi (AD 1130 – 1200) added ideas from Daoism and Buddhism

into Confucianism. In his life, Zhu Xi was largely ignored, but not

long after his death his ideas became the new orthodox view of what

Confucian texts actually meant. Modern historians view Zhu Xi as having

created something rather different, and call his way of thinking Neo - Confucianism. Neo - Confucianism held sway in China, Japan, Korea and Vietnam until the 19th century.

The works of Confucius were translated into European languages through the agency of Jesuit scholars stationed in China. Matteo Ricci started to report on the thoughts of Confucius, and father Prospero Intorcetta published the life and works of Confucius into Latin in 1687. It is thought that such works had considerable importance on European thinkers of the period, particularly among the Deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Western civilization.

In the modern era Confucian movements, such as New Confucianism, still exist but during the Cultural Revolution, Confucianism was frequently attacked by leading figures in the Communist Party of China. This was partially a continuation of the condemnations of Confucianism by intellectuals and activists in the early 20th Century as a cause of the ethnocentric close - mindedness and refusal of the Qing Dynasty to modernize that led to the tragedies that befell China in the 19th Century.

Confucius's works are studied by scholars in many other Asian countries, particularly those in the Sinosphere, such as Korea, Japan and Vietnam. Many of those countries still hold the traditional memorial ceremony every year.

The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community believes Confucius was a Divine Prophet of God, as was Lao-Tzu and other eminent Chinese personages.

In modern times, Asteroid 7853, "Confucius", was named after the Chinese thinker.

No contemporary painting or sculpture of Confucius survives, and it was only during the Han Dynasty that he was portrayed visually. Carvings often depict his legendary meeting with Laozi. Since that time there have been many portraits of Confucius as the ideal philosopher.

In former times, it was customary to have a portrait in Confucius Temples; however, during the reign of Hongwu Emperor (Taizu) of the Ming dynasty it was decided that the only proper portrait of Confucius should be in the temple in his hometown, Qufu. In other temples, Confucius is represented by a memorial tablet. In 2006, the China Confucius Foundation commissioned a standard portrait of Confucius based on the Tang dynasty portrait by Wu Daozi.

Burdened by the loss of both his son and his favorite disciples, he died at the age of 71 or 72. Confucius was buried in Kong Lin cemetery which lies in the historical part of Qufu.

The original tomb erected there in memory of Confucius on the bank of

the Sishui River had the shape of an axe. In addition, it has a raised

brick platform at the front of the memorial for offerings such as

sandalwood incense and fruit.

Soon after Confucius' death, Qufu, his hometown became a place of devotion and remembrance. It is still a major destination for cultural tourism, and many people visit his grave and the surrounding temples. In pan - China cultures, there are many temples where representations of the Buddha, Laozi and Confucius are found together. There are also many temples dedicated to him, which have been used for Confucianist ceremonies.

The Chinese have a tradition of holding spectacular memorial ceremonies of Confucius (祭孔) every year, using ceremonies that supposedly derived from Zhou Li (周禮) as recorded by Confucius, on the date of Confucius' birth. This tradition was interrupted for several decades in mainland China, where the official stance of the Communist Party and the State was that Confucius and Confucianism represented reactionary feudalist beliefs which held that the subservience of the people to the aristocracy is a part of the natural order. All such ceremonies and rites were therefore banned. Only after the 1990s, did the ceremony resume. As it is now considered a veneration of Chinese history and tradition, even Communist Party members may be found in attendance.

In Taiwan, where the Nationalist Party (Kuomintang)

strongly promoted Confucian beliefs in ethics and behavior, the

tradition of the memorial ceremony of Confucius (祭孔) is supported by the

government and has continued without interruption. While not a national

holiday, it does appear on all printed calendars, much as Father's Day does in the West.

Confucius' descendants were repeatedly identified and honored by successive imperial governments with titles of nobility and official posts. They were honored with the rank of a marquis thirty - five times since Gaozu of the Han Dynasty, and they were promoted to the rank of duke forty - two times from the Tang Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty. Emperor Xuanzong of Tang first bestowed the title of "Duke Wenxuan" on Kong Suizhi of the 35th generation. In 1055, Emperor Renzong of Song first bestowed the title of "Duke Yansheng" on Kong Zongyuan of the 46th generation.

Despite repeated dynastic change in China, the title of Duke Yansheng was bestowed upon successive generations of descendants until it was abolished by the Nationalist Government in 1935. The last holder of the title, Kung Te-cheng of the 77th generation, was appointed Sacrificial Official to Confucius. Kung Te-cheng died in October 2008, and his son, Kung Wei-yi, the 78th lineal descendant, had died in 1989. Kung Te-cheng's grandson, Kung Tsui-chang, the 79th lineal descendant, was born in 1975; his great - grandson, Kung Yu-jen, the 80th lineal descendant, was born in Taipei on January 1, 2006. Te-cheng's sister, Kong Demao, lives in mainland China and has written a book about her experiences growing up at the family estate in Qufu. Another sister, Kong Deqi, died as a young woman.

Confucius's family, the Kongs, has the longest recorded extant pedigree in the world today. The father - to - son family tree, now in its 83rd generation, has been recorded since the death of Confucius. According to the Confucius Genealogy Compilation Committee, he has 2 million known and registered descendants, and there are an estimated 3 million in all. Of these, several tens of thousands live outside of China. In the 14th century, a Kong descendant went to Korea, where an estimated 34,000 descendants of Confucius live today. One of the main lineages fled from the Kong ancestral home in Qufu during the Chinese Civil War in the 1940s, and eventually settled in Taiwan.

Because of the huge interest in the Confucius family tree, there was a project in China to test the DNA of known family members. Among other things, this would allow scientists to identify a common Y chromosome in male descendants of Confucius. If the descent were truly unbroken, father - to - son, since Confucius's lifetime, the males in the family would all have the same Y chromosome as their direct male ancestor, with slight mutations due to the passage of time. However, in 2009, the family authorities decided not to agree to DNA testing. Bryan Sykes, professor of genetics at Oxford University, understands this decision: "The Confucius family tree has an enormous cultural significance," he said. "It's not just a scientific question." The DNA testing was originally proposed to add new members, many of whose family record books were lost during 20th century upheavals, to the Confucian family tree.

The fifth and most recent edition of the Confucius genealogy was printed by the Confucius Genealogy Compilation Committee (CGCC). It was unveiled in a ceremony at Qufu on September 24, 2009. Women are now included for the first time.

Note that this only deals with those whose lines of descent are

documented historically. Using mathematical models, it is easy to

demonstrate that people living today have a much more common ancestry

than commonly assumed, so it is likely that many more have Confucius as

an ancestor.

Plato (Greek: Πλάτων, Plátōn, "broad"; 424 / 423 BC – 348 / 347 BC) was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the foundations of Western philosophy and science. In the words of A. N. Whitehead:

The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato. I do not mean the systematic scheme of thought which scholars have doubtfully extracted from his writings. I allude to the wealth of general ideas scattered through them.

Plato's sophistication as a writer is evident in his Socratic dialogues;

thirty - six dialogues and thirteen letters have been ascribed to him.

Plato's writings have been published in several fashions; this has led

to several conventions regarding the naming and referencing of Plato's

texts. Plato's dialogues have been used to teach a range of subjects, including philosophy, logic, ethics, rhetoric and mathematics.

The exact place and time of Plato's birth are not known, but it is certain that he belonged to an aristocratic and influential family. Based on ancient sources, most modern scholars believe that he was born in Athens or Aegina between 429 and 423 BC. His father was Ariston. According to a disputed tradition, reported by Diogenes Laertius, Ariston traced his descent from the king of Athens, Codrus, and the king of Messenia, Melanthus. Plato's mother was Perictione, whose family boasted of a relationship with the famous Athenian lawmaker and lyric poet Solon. Perictione was sister of Charmides and niece of Critias, both prominent figures of the Thirty Tyrants, the brief oligarchic regime, which followed on the collapse of Athens at the end of the Peloponnesian War (404 – 403 BC). Besides Plato himself, Ariston and Perictione had three other children; these were two sons, Adeimantus and Glaucon, and a daughter Potone, the mother of Speusippus (the nephew and successor of Plato as head of his philosophical Academy). According to the Republic, Adeimantus and Glaucon were older than Plato. Nevertheless, in his Memorabilia, Xenophon presents Glaucon as younger than Plato.

The traditional date of Plato's birth (428 / 427) is based on a dubious interpretation of Diogenes Laertius, who says, "When [Socrates] was gone, [Plato] joined Cratylus the Heracleitean and Hermogenes, who philosophized in the manner of Parmenides. Then, at twenty - eight, Hermodorus says, [Plato] went to Euclides in Megara." As Debra Nails argues, "The text itself gives no reason to infer that Plato left immediately for Megara and implies the very opposite." In his Seventh Letter Plato notes that his coming of age coincided with the taking of power by the Thirty, remarking, "But a youth under the age of twenty made himself a laughingstock if he attempted to enter the political arena." Thus Nails dates Plato's birth to 424 / 423.

According to some accounts, Ariston tried to force his attentions on Perictione, but failed in his purpose; then the god Apollo appeared to him in a vision, and as a result, Ariston left Perictione unmolested. Another legend related that, when Plato was an infant, bees settled on his lips while he was sleeping: an augury of the sweetness of style in which he would discourse philosophy.

Ariston appears to have died in Plato's childhood, although the precise dating of his death is difficult. Perictione then married Pyrilampes, her mother's brother, who had served many times as an ambassador to the Persian court and was a friend of Pericles, the leader of the democratic faction in Athens. Pyrilampes had a son from a previous marriage, Demus, who was famous for his beauty. Perictione gave birth to Pyrilampes' second son, Antiphon, the half brother of Plato, who appears in Parmenides.

In contrast to his reticence about himself, Plato often introduced his distinguished relatives into his dialogues, or referred to them with some precision: Charmides has a dialogue named after him; Critias speaks in both Charmides and Protagoras; and Adeimantus and Glaucon take prominent parts in the Republic. These and other references suggest a considerable amount of family pride and enable us to reconstruct Plato's family tree. According to Burnet, "the opening scene of the Charmides is a glorification of the whole [family] connection ... Plato's dialogues are not only a memorial to Socrates, but also the happier days of his own family."

According to Diogenes Laërtius, the philosopher was named Aristocles

after his grandfather, but his wrestling coach, Ariston of Argos,

dubbed him "Platon", meaning "broad," on account of his robust figure.

According to the sources mentioned by Diogenes (all dating from the Alexandrian period), Plato derived his name from the breadth (platytês) of his eloquence, or else because he was very wide (platýs) across the forehead. In the 21st century some scholars disputed Diogenes, and argued that the legend about his name being Aristocles originated in the Hellenistic age.

Apuleius

informs us that Speusippus praised Plato's quickness of mind and

modesty as a boy, and the "first fruits of his youth infused with hard

work and love of study".

Plato must have been instructed in grammar, music and gymnastics by the

most distinguished teachers of his time. Dicaearchus went so far as to

say that Plato wrestled at the Isthmian games.

Plato had also attended courses of philosophy; before meeting Socrates,

he first became acquainted with Cratylus (a disciple of Heraclitus, a

prominent pre-Socratic Greek philosopher) and the Heraclitean doctrines.

The precise relationship between Plato and Socrates remains an area of contention among scholars. Plato makes it clear in his Apology of Socrates, that he was a devoted young follower. In that dialogue, Socrates is presented as mentioning Plato by name as one of those youths close enough to him to have been corrupted, if he were in fact guilty of corrupting the youth, and questioning why their fathers and brothers did not step forward to testify against him if he was indeed guilty of such a crime (33d - 34a). Later, Plato is mentioned along with Crito, Critobolus, and Apollodorus as offering to pay a fine of 30 minas on Socrates' behalf, in lieu of the death penalty proposed by Meletus (38b). In the Phaedo, the title character lists those who were in attendance at the prison on Socrates' last day, explaining Plato's absence by saying, "Plato was ill" (Phaedo 59b).

Plato never speaks in his own voice in his dialogues. In the Second Letter, it says, "no writing of Plato exists or ever will exist, but those now said to be his are those of a Socrates become beautiful and new" (341c); if the Letter is Plato's, the final qualification seems to call into question the dialogues' historical fidelity. In any case, Xenophon and Aristophanes seem to present a somewhat different portrait of Socrates than Plato paints. Some have called attention to the problem of taking Plato's Socrates to be his mouthpiece, given Socrates' reputation for irony and the dramatic nature of the dialogue form.

Aristotle attributes a different doctrine with respect to the ideas to Plato and Socrates (Metaphysics

987b1 – 11). Putting it in a nutshell, Aristotle merely suggests that his

idea of forms can be discovered through investigation of the natural

world, unlike Plato's Forms that exist beyond and outside the ordinary

range of human understanding.

Plato may have traveled in Italy, Sicily, Egypt and Cyrene. Said to have returned to Athens at the age of forty, Plato founded one of the earliest known organized schools in Western Civilization on a plot of land in the Grove of Hecademus or Academus. The Academy was "a large enclosure of ground that was once the property of a citizen at Athens named Academus (some, however, say that it received its name from an ancient hero). The Academy operated until it was destroyed by Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 84 BC. Neoplatonists revived the Academy in the early 5th century, and it operated until AD 529, when it was closed by Justinian I of Byzantium, who saw it as a threat to the propagation of Christianity. Many intellectuals were schooled in the Academy, the most prominent one being Aristotle.

Throughout his later life, Plato became entangled with the politics of the city of Syracuse. According to Diogenes Laertius, Plato initially visited Syracuse while it was under the rule of Dionysus. During this first trip Dionysus's brother - in - law, Dion of Syracuse, became one of Plato's disciples, but the tyrant himself turned against Plato. Plato was sold into slavery and almost faced death in Cyrene, a city at war with Athens, before an admirer bought Plato's freedom and sent him home. After Dionysius's death, according to Plato's Seventh Letter, Dion requested Plato return to Syracuse to tutor Dionysus II and guide him to become a philosopher king. Dionysius II seemed to accept Plato's teachings, but he became suspicious of Dion, his uncle. Dionysus expelled Dion and kept Plato against his will. Eventually Plato left Syracuse. Dion would return to overthrow Dionysus and ruled Syracuse for a short time before being usurped by Calippus, a fellow disciple of Plato.

A variety of sources have given accounts of Plato's death. One story,

based on a mutilated manuscript, suggests Plato died in his bed, whilst a

young Thracian girl played the flute to him.

Another tradition suggests Plato died at a wedding feast. The account

is based on Diogenes Laertius's reference to an account by Hermippus, a

third century Alexandrian. According to Tertullian, Plato simply died in his sleep.

Plato often discusses the father - son relationship and the "question" of whether a father's interest in his sons has much to do with how well his sons turn out. A boy in ancient Athens was socially located by his family identity, and Plato often refers to his characters in terms of their paternal and fraternal relationships. Socrates was not a family man, and saw himself as the son of his mother, who was apparently a midwife. A divine fatalist, Socrates mocks men who spent exorbitant fees on tutors and trainers for their sons, and repeatedly ventures the idea that good character is a gift from the gods. Crito reminds Socrates that orphans are at the mercy of chance, but Socrates is unconcerned. In the Theaetetus, he is found recruiting as a disciple a young man whose inheritance has been squandered. Socrates twice compares the relationship of the older man and his boy lover to the father - son relationship (Lysis 213a, Republic 3.403b), and in the Phaedo, Socrates' disciples, towards whom he displays more concern than his biological sons, say they will feel "fatherless" when he is gone.

In several dialogues, Socrates floats the idea that knowledge is a matter of recollection, and not of learning, observation, or study. He maintains this view somewhat at his own expense, because in many dialogues, Socrates complains of his forgetfulness. Socrates is often found arguing that knowledge is not empirical, and that it comes from divine insight. In many middle period dialogues, such as the Phaedo, Republic and Phaedrus Plato advocates a belief in the immortality of the soul, and several dialogues end with long speeches imagining the afterlife. More than one dialogue contrasts knowledge and opinion, perception and reality, nature and custom, and body and soul.

Several dialogues tackle questions about art: Socrates says that poetry is inspired by the muses, and is not rational. He speaks approvingly of this, and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism and dreaming) in the Phaedrus (265a–c), and yet in the Republic wants to outlaw Homer's great poetry, and laughter as well. In Ion, Socrates gives no hint of the disapproval of Homer that he expresses in the Republic. The dialogue Ion suggests that Homer's Iliad functioned in the ancient Greek world as the Bible does today in the modern Christian world: as divinely inspired literature that can provide moral guidance, if only it can be properly interpreted.

On politics and art, religion and science, justice and medicine,

virtue and vice, crime and punishment, pleasure and pain, rhetoric and

rhapsody, human nature and sexuality, love and wisdom, Socrates and his

company of disputants had something to say.

"Platonism" is a term coined by scholars to refer to the intellectual consequences of denying, as Socrates often does, the reality of the material world. In several dialogues, most notably the Republic, Socrates inverts the common man's intuition about what is knowable and what is real. While most people take the objects of their senses to be real if anything is, Socrates is contemptuous of people who think that something has to be graspable in the hands to be real. In the Theaetetus, he says such people are "eu a-mousoi", an expression that means literally, "happily without the muses" (Theaetetus 156a). In other words, such people live without the divine inspiration that gives him, and people like him, access to higher insights about reality.

Socrates's idea that reality is unavailable to those who use their senses is what puts him at odds with the common man, and with common sense. Socrates says that he who sees with his eyes is blind, and this idea is most famously captured in his allegory of the cave, and more explicitly in his description of the divided line. The allegory of the cave (begins Republic 7.514a) is a paradoxical analogy wherein Socrates argues that the invisible world is the most intelligible ("noeton") and that the visible world ("(h)oraton") is the least knowable, and the most obscure.

Socrates says in the Republic that people who take the sun - lit world of the senses to be good and real are living pitifully in a den of evil and ignorance. Socrates admits that few climb out of the den, or cave of ignorance, and those who do, not only have a terrible struggle to attain the heights, but when they go back down for a visit or to help other people up, they find themselves objects of scorn and ridicule.

According to Socrates, physical objects and physical events are "shadows" of their ideal or perfect forms, and exist only to the extent that they instantiate the perfect versions of themselves. Just as shadows are temporary, inconsequential epiphenomena produced by physical objects, physical objects are themselves fleeting phenomena caused by more substantial causes, the ideals of which they are mere instances. For example, Socrates thinks that perfect justice exists (although it is not clear where) and his own trial would be a cheap copy of it.

The allegory of the cave (often said by scholars to represent Plato's own epistemology and metaphysics) is intimately connected to his political ideology (often said to also be Plato's own), that only people who have climbed out of the cave and cast their eyes on a vision of goodness are fit to rule. Socrates claims that the enlightened men of society must be forced from their divine contemplations and be compelled to run the city according to their lofty insights. Thus is born the idea of the "philosopher - king", the wise person who accepts the power thrust upon him by the people who are wise enough to choose a good master. This is the main thesis of Socrates in the Republic, that the most wisdom the masses can muster is the wise choice of a ruler.

The word metaphysics derives from the fact that Aristotle's musings about divine reality came after ("meta") his lecture notes on his treatise on nature ("physics"). The term is in fact applied to Aristotle's own teacher, and Plato's "metaphysics" is understood as Socrates' division of reality into the warring and irreconcilable domains of the material and the spiritual. The theory has been of incalculable influence in the history of Western philosophy and religion.

The Theory of Forms (Greek: ἰδέαι)

typically refers to the belief expressed by Socrates in some of Plato's

dialogues, that the material world as it seems to us is not the real

world, but only an image or copy of the real world. Socrates spoke of

forms in formulating a solution to the problem of universals. The forms,

according to Socrates, are roughly speaking archetypes or abstract

representations of the many types of things, and properties we feel and see around us, that can only be perceived by reason (Greek: λογική); (that is, they are universals).

In other words, Socrates sometimes seems to recognize two worlds: the

apparent world, which constantly changes, and an unchanging and unseen

world of forms, which may be a cause of what is apparent.

Many have interpreted Plato as stating that knowledge is justified true belief, an influential view that informed future developments in modern analytic epistemology. This interpretation is based on a reading of the Theaetetus wherein Plato argues that belief is to be distinguished from knowledge on account of justification. Many years later, Edmund Gettier famously demonstrated the problems of the justified true belief account of knowledge. This interpretation, however, imports modern analytic and empiricist categories onto Plato himself and is better read on its own terms than as Plato's view.

Really, in the Sophist, Statesman, Republic, and the Parmenides Plato himself associates knowledge with the apprehension of unchanging Forms and their relationships to one another (which he calls "expertise" in Dialectic). More explicitly, Plato himself argues in the Timaeus that knowledge is always proportionate to the realm from which it is gained. In other words, if one derives one's account of something experientially, because the world of sense is in flux, the views therein attained will be mere opinions. And opinions are characterized by a lack of necessity and stability. On the other hand, if one derives one's account of something by way of the non - sensible forms, because these forms are unchanging, so too is the account derived from them. It is only in this sense that Plato uses the term "knowledge".

In the Meno, Socrates uses a

geometrical example to expound Plato's view that knowledge in this

latter sense is acquired by recollection. Socrates elicits a fact

concerning a geometrical construction from a

slave boy, who could not have otherwise known the fact (due to the slave

boy's lack of education). The knowledge must be present, Socrates

concludes, in an eternal, non - experiential form.

Plato's philosophical views had many societal implications, especially on the idea of an ideal state or government. There is some discrepancy between his early and later views. Some of the most famous doctrines are contained in the Republic during his middle period, as well as in the Laws and the Statesman. However, because Plato wrote dialogues, it is assumed that Socrates is often speaking for Plato. This assumption may not be true in all cases.

Plato, through the words of Socrates, asserts that societies have a tripartite class structure corresponding to the appetite / spirit / reason structure of the individual soul. The appetite / spirit / reason stand for different parts of the body. The body parts symbolize the castes of society.

- Productive, which represents the abdomen. (Workers) — the laborers, carpenters, plumbers, masons, merchants, farmers, ranchers, etc. These correspond to the "appetite" part of the soul.

- Protective, which represents the chest. (Warriors or Guardians) — those who are adventurous, strong and brave; in the armed forces. These correspond to the "spirit" part of the soul.

- Governing, which represents the head. (Rulers or Philosopher Kings) — those who are intelligent, rational, self - controlled, in love with wisdom, well suited to make decisions for the community. These correspond to the "reason" part of the soul and are very few.

According to this model, the principles of Athenian democracy (as it existed in his day) are rejected as only a few are fit to rule. Instead of rhetoric and persuasion, Plato says reason and wisdom should govern. As Plato puts it:

- "Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophize, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide, while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively are forcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils,... nor, I think, will the human race." (Republic 473c-d)

Plato describes these "philosopher kings" as "those who love the sight of truth" (Republic 475c) and supports the idea with the analogy of a captain and his ship or a doctor and his medicine. According to him, sailing and health are not things that everyone is qualified to practice by nature. A large part of the Republic then addresses how the educational system should be set up to produce these philosopher kings.

However, it must be taken into account that the ideal city outlined in the Republic is qualified by Socrates as the ideal luxurious city, examined to determine how it is that injustice and justice grow in a city (Republic 372e). According to Socrates, the "true" and "healthy" city is instead the one first outlined in book II of the Republic, 369c – 372d, containing farmers, craftsmen, merchants and wage earners, but lacking the guardian class of philosopher - kings as well as delicacies such as "perfumed oils, incense, prostitutes and pastries", in addition to paintings, gold, ivory, couches, a multitude of occupations such as poets and hunters, and war.

In addition, the ideal city is used as an image to illuminate the state of one's soul, or the will, reason and desires combined in the human body. Socrates is attempting to make an image of a rightly ordered human, and then later goes on to describe the different kinds of humans that can be observed, from tyrants to lovers of money in various kinds of cities. The ideal city is not promoted, but only used to magnify the different kinds of individual humans and the state of their soul. However, the philosopher king image was used by many after Plato to justify their personal political beliefs. The philosophic soul according to Socrates has reason, will and desires united in virtuous harmony. A philosopher has the moderate love for wisdom and the courage to act according to wisdom. Wisdom is knowledge about the Good or the right relations between all that exists.

Wherein it concerns states and rulers, Plato has made interesting arguments. For instance he asks which is better — a bad democracy or a country reigned by a tyrant. He argues that it is better to be ruled by a bad tyrant, than be a bad democracy (since here all the people are now responsible for such actions, rather than one individual committing many bad deeds.) This is emphasized within the Republic as Plato describes the event of mutiny onboard a ship. Plato suggests the ships crew to be in line with the democratic rule of many and the captain, although inhibited through ailments, the tyrant. Plato's description of this event is parallel to that of democracy within the state and the inherent problems that arise.

According to Plato, a state made up of different kinds of souls will,

overall, decline from an aristocracy (rule by the best) to a timocracy

(rule by the honorable), then to an oligarchy (rule by the few), then to

a democracy (rule by the people), and finally to tyranny (rule by one person, rule by a tyrant).

For a long time Plato's unwritten doctrine had been controversial. Many modern books on Plato seem to diminish its importance; nevertheless the first important witness who mentions its existence is Aristotle, who in his Physics (209 b) writes: "It is true, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e., in Timaeus] of the participant is different from what he says in his so-called unwritten teachings (ἄγραφα δόγματα)." The term ἄγραφα δόγματα literally means unwritten doctrines and it stands for the most fundamental metaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some say only to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from the public. The importance of the unwritten doctrines does not seem to have been seriously questioned before the 19th century.

A reason for not revealing it to everyone is partially discussed in Phaedrus (276 c) where Plato criticizes the written transmission of knowledge as faulty, favoring instead the spoken logos: "he who has knowledge of the just and the good and beautiful ... will not, when in earnest, write them in ink, sowing them through a pen with words, which cannot defend themselves by argument and cannot teach the truth effectually." The same argument is repeated in Plato's Seventh Letter (344 c): "every serious man in dealing with really serious subjects carefully avoids writing." In the same letter he writes (341 c): "I can certainly declare concerning all these writers who claim to know the subjects that I seriously study ... there does not exist, nor will there ever exist, any treatise of mine dealing therewith." Such secrecy is necessary in order not "to expose them to unseemly and degrading treatment" (344 d).

It is however said that Plato once disclosed this knowledge to the public in his lecture On the Good (Περὶ τἀγαθοῦ), in which the Good (τὸ ἀγαθόν) is identified with the One (the Unity, τὸ ἕν), the fundamental ontological principle. The content of this lecture has been transmitted by several witnesses, among others Aristoxenus who describes the event in the following words: "Each came expecting to learn something about the things that are generally considered good for men, such as wealth, good health, physical strength, and altogether a kind of wonderful happiness. But when the mathematical demonstrations came, including numbers, geometrical figures and astronomy, and finally the statement Good is One seemed to them, I imagine, utterly unexpected and strange; hence some belittled the matter, while others rejected it." Simplicius quotes Alexander of Aphrodisias who states that "according to Plato, the first principles of everything, including the Forms themselves are One and Indefinite Duality (ἡ ἀόριστος δυάς), which he called Large and Small (τὸ μέγα καὶ τὸ μικρόν) ... one might also learn this from Speusippus and Xenocrates and the others who were present at Plato's lecture on the Good"

Their account is in full agreement with Aristotle's description of Plato's metaphysical doctrine. In Metaphysics he writes: "Now since the Forms are the causes of everything else, he [i.e., Plato] supposed that their elements are the elements of all things. Accordingly the material principle is the Great and Small [i.e., the Dyad], and the essence is the One (τὸ ἕν), since the numbers are derived from the Great and Small by participation in the One" (987 b). "From this account it is clear that he only employed two causes: that of the essence, and the material cause; for the Forms are the cause of the essence in everything else, and the One is the cause of it in the Forms. He also tells us what the material substrate is of which the Forms are predicated in the case of sensible things, and the One in that of the Forms - that it is this the duality (the Dyad, ἡ δυάς), the Great and Small (τὸ μέγα καὶ τὸ μικρόν). Further, he assigned to these two elements respectively the causation of good and of evil" (988 a).

The most important aspect of this interpretation of Plato's metaphysics is the continuity between his teaching and the neoplatonic interpretation of Plotinus or Ficino which has been considered erroneous by many but may in fact have been directly influenced by oral transmission of Plato's doctrine. A modern scholar who recognized the importance of the unwritten doctrine of Plato was Heinrich Gomperz who described it in his speech during the 7th International Congress of Philosophy in 1930. All the sources related to the ἄγραφα δόγματα have been collected by Konrad Gaiser and published as Testimonia Platonica. These sources have subsequently been interpreted by scholars from the German Tübingen School such as Hans Joachim Krämer or Thomas A. Szlezák.

The role of dialectic in Plato's thought is contested but there are two main interpretations; a type of reasoning and a method of intuition. Simon Blackburn adopts the first, saying that Plato's dialectic is “the process of eliciting the truth by means of questions aimed at opening out what is already implicitly known, or at exposing the contradictions and muddles of an opponent’s position.” Karl Popper, on the other hand, claims that dialectic is the art of intuition for "visualizing the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances."