<Back to Index>

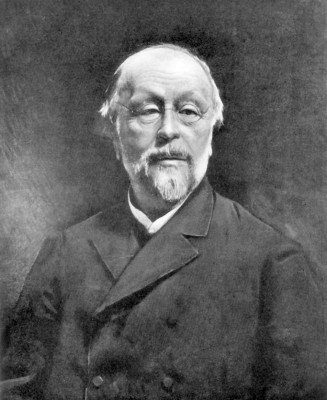

- Critic and Historian Hippolyte Adolphe Taine, 1828

- Historian, Political Theorist and Sociologist William Graham Sumner, 1840

PAGE SPONSOR

Hippolyte Adolphe Taine (21 April 1828 – 5 March 1893) was a French critic and historian. He was the chief theoretical influence of French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism, and one of the first practitioners of historicist criticism. Literary historicism as a critical movement has been said to originate with him. Taine is particularly remembered for his three - pronged approach to the contextual study of a work of art, based on the aspects of what he called "race, milieu and moment".

Taine had a profound effect on French literature; the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica asserted that "the tone which pervades the works of Zola, Bourget and Maupassant can be immediately attributed to the influence we call Taine's."

Taine was born in Vouziers, but entered a boarding school, the Institution Mathé, whose classes were conducted at the Collège Bourbon, at the age of 13 in 1841, after the death of his father.

He excelled as a student, receiving a number of prizes in both

scientific and humanistic subjects, and taking two Baccalauréat degrees

at the École Normale before he was 20. Taine's contrarian politics led

to difficulties keeping teaching posts, and his early academic career

was decidedly mixed; he failed the exam for the national Concours d'Agrégation in 1851. After his dissertation on sensation was rejected, he abandoned his studies in the social sciences, feeling that literature was safer. He completed a doctorate at the Sorbonne in 1853, with considerably more success in his new field; his dissertation, Essai sur les fables de La Fontaine, won him a prize from the Académie française.

Taine was criticized, in his own time and after, by both conservatives and liberals; his politics were idiosyncratic, but had a consistent streak of skepticism toward the left; at the age of 20, he wrote that "the right of property is absolute." Peter Gay describes Taine's reaction to the Jacobins as stigmatization, drawing on The French Revolution, in which Taine argues:

Some of the workmen are shrewd Politicians whose sole object is to furnish the public with words instead of things; others, ordinary scribblers of abstractions, or even ignoramuses, and unable to distinguish words from things, imagine that they are framing laws by stringing together a lot of phrases.

This reaction led Taine to reject the French Constitution of 1793 as a Jacobin document, dishonestly presented to the French people. Taine rejected the principles of the Revolution in favor of the individualism of his concepts of regionalism and race, to the point that one writer calls him one of "the most articulate exponents of both French nationalism and conservatism."

Other writers, however, have argued that, though Taine displayed

increasing conservatism throughout his career, he also formulated an

alternative to rationalist liberalism that was influential for the

social policies of the Third Republic. Taine's complex politics have

remained hard to read; though admired by liberals like Anatole France,

he has been the object of considerable disdain in the twentieth

century, with a few historians working to revive his reputation.

Taine is best known now for his attempt at a scientific account of literature, based on the categories of race, milieu and moment. Taine used these words in French (race, milieu et moment); the terms have become widespread in literary criticism in English, but are used in this context in senses closer to the French meanings of the words than the English meanings, which are, roughly, "nation", "environment" or "situation", and "time".

Taine argued that literature was largely the product of the author's environment, and that an analysis of that environment could yield a perfect understanding of the work of literature. In this sense he was a sociological positivist (see Auguste Comte), though with important differences. Taine did not mean race in the specific sense now common, but rather the collective cultural dispositions that govern everyone without their knowledge or consent. What differentiates individuals within this collective "race", for Taine, was milieu: the particular circumstances that distorted or developed the dispositions of a particular person. The "moment" is the accumulated experiences of that person, which Taine often expressed as momentum; to some later critics, however, Taine's conception of moment seemed to have more in common with Zeitgeist.

Though Taine coined and popularized the phrase "race, milieu et moment," the theory itself has roots in earlier attempts to understand the aesthetic

object as a social product rather than a spontaneous creation of

genius. Taine seems to have drawn heavily on the philosopher Johann

Gottfried Herder's ideas of volk (people) and nation in his own

concept of race; the Spanish writer Emilia Pardo Bazán has suggested

that a crucial predecessor to Taine's idea was the work of Germaine de Staël on the relationship between art and society.

Taine's influence on French intellectual culture and literature was enormous. He had a special relationship, in particular, with Émile Zola. As critic Philip Walker says of Zola, "In page after page, including many of his most memorable writings, we are presented with what amounts to a mimesis of the interplay between sensation and imagination which Taine studied at great length and out of which, he believed, emerges the world of the mind." Zola's reliance on Taine, however, was occasionally seen as a fault; Miguel de Unamuno, after an early fascination with both Zola and Taine, eventually concluded that Taine's influence on literature was, all in all, negative.

Taine also influenced a number of nationalist literary movements throughout the world, who used his ideas to argue that their particular countries had a distinct literature and thus a distinct place in literary history. In addition, post modern literary critics concerned with the relationship between literature and social history (including the New Historicists) continue to cite Taine's work, and to make use of the idea of race, milieu and moment. The critic John Chapple, for example, has used the term as an illustration of his own concept of "composite history."

Taine was the subject of Stefan Zweig's doctoral thesis, "The Philosophy of Hippolyte Taine."

The chief criticism of race, milieu, and moment at the time the idea was created was that it did not sufficiently take into account the individuality of the artist, central to the creative genius of Romanticism. Even Zola, who owed so much to Taine, made this objection, arguing that an artist's temperament could lead him to make unique artistic choices distinct from the environment that shaped his general viewpoint; Zola's principal example was the painter Édouard Manet. Similarly, Gustave Lanson argued that race, milieu, and moment could not among themselves account for genius; Taine, he felt, explained mediocrity better than he explained greatness.

A distinct criticism concerns the possible sloppiness of the logic

and scientific basis of the three concepts. As Leo Spitzer has written,

the actual science of the idea, which is vaguely Darwinian, is rather

tenuous, and shortly after Taine's work was published a number of

objections were made on scientific grounds.

Spitzer also points out, again citing period sources, that the

relationship between the three terms themselves was never well

understood, and that it is possible to argue that moment is an

unnecessary addition implied by the other two.

William Graham Sumner (October 30, 1840 – April 12, 1910) was an American academic and "held the first professorship in sociology" at Yale College. For many years he had a reputation as one of the most influential teachers there. He was a polymath with numerous books and essays on American history, economic history, political theory, sociology and anthropology. He is credited with introducing the term "ethnocentrism," a term intended to identify imperialists' chief means of justification, in his book Folkways (1906). Sumner is often seen as a proto - libertarian. He was also the first to teach a course entitled "Sociology". Sumner was a critic of natural rights, famously arguing

Born in Paterson, New Jersey, Sumner graduated from Yale College in 1863, where he had been a member of Skull and Bones. During the late 1860s Sumner was an Episcopalian minister. In 1872, Sumner accepted the chair of Political Economy at Yale University."Before the tribunal of nature a man has no more right to life than a rattlesnake; he has no more right to liberty than any wild beast; his right to pursuit of happiness is nothing but a license to maintain the struggle for existence..."—William Graham Sumner, "Earth - hunger, and other essays".

Sumner was a staunch advocate of laissez - faire economics, as well as "a forthright proponent of free trade and the gold standard and a foe of socialism." Sumner was active in the intellectual promotion of free trade classical liberalism, and in his heyday and after there were Sumner Clubs here and there. He heavily criticized state socialism / state communism. One adversary he mentioned by name was Edward Bellamy, whose national variant of socialism was set forth in Looking Backward, published in 1888, and the sequel Equality.

Like many classical liberals at the time, including Edward Atkinson, Moorfield Storey, and Grover Cleveland, Sumner opposed the Spanish - American War and the subsequent U.S. effort to quell the insurgency in the Philippines. He was a vice president of the Anti - Imperialist League which had been formed after the war to oppose the annexation of territories. In his speech "The Conquest of the United States by Spain," (considered by some to be "his most enduring work") he lambasted imperialism as a betrayal of the best traditions, principles and interests of the American People and contrary to America's own founding as a state of equals, where justice and law "were to reign in the midst of simplicity". In this ironically titled work, Sumner portrayed the takeover as "an American version of the imperialism and lust for colonies that had brought Spain the sorry state of his own time". According to Sumner, imperialism would enthrone a new group of "plutocrats", or businesspeople who depended on government subsidies and contracts.

As a sociologist, his major accomplishments were developing the concepts of diffusion, folkways and ethnocentrism. Sumner's work with folkways led him to conclude that attempts at government mandated reform were useless.

In 1875, Sumner became the first to teach a course entitled "sociology" in the English speaking world, though this course focused on the thought of Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer, rather than the formal academic sociology that would be established 20 years later by Émile Durkheim in Europe. He was the second president of American Sociological Association serving from 1908 to 1909 and succeeding his long time ideological opponent Lester F. Ward.

In 1880, Sumner was involved in one of the first cases of academic

freedom. Sumner and the Yale president at the time, Noah Porter, did not

agree on the use of Herbert Spencer's "Study of Sociology" as part of

the curriculum.

Spencer's application of Darwinist ideas to the realm of humans may

have been slightly too controversial at this time of curriculum reform.

On the other hand even if Spencer's ideas were not generally accepted,

it is clear that his social Darwinist ideas influenced Sumner in his

written works.

William Graham Sumner was influenced by many people and ideas such as Herbert Spencer and his social Darwinist ideologies.

In 1881 Sumner wrote an essay entitled “Sociology”. In the essay Sumner focuses on the connection between sociology and biology. He explains that there are two sides to the struggle for survival of a human. The first being a “struggle for existence”, which is a relationship between man and nature. The second side would be the “competition for life” which can be identified as a relationship between man and man. The first being a biological relationship with nature and the second being a social link thus sociology. Man would struggle against nature to obtain essential needs such food or water and in turn this would create the conflict between man and man in order to obtain needs from a limited supply. Sumner believed that man could not abolish the law of “survival of the fittest” but could only interfere with it and produce the “unfit”.

According to Jeff Riggenbach, the identification of Sumner as a Social Darwinist

| “ | is ironic, for he was not so known during his lifetime or for many years thereafter. Robert C. Bannister, the Swarthmore historian, . . . describes the situation: "Sumner's 'social Darwinism,'" he writes, "although rooted in controversies during his lifetime, received its most influential expression in Richard Hofstadter['s] Social Darwinism in American Thought," which was first published in 1944. . . . Was William Graham Sumner an advocate of "social Darwinism"? As I have indicated, he has been so described, most notably by Richard Hofstadter and various others over the past 60-odd years. Robert Bannister calls this description "more caricature than accurate characterization" of Sumner, however, and says further that it "seriously misrepresents him." He notes that Sumner's short book, What Social Classes Owe to Each Other, which was first published in 1884, when the author was in his early 40s, "would … earn him a reputation as the Gilded Age's leading 'social Darwinist,'" though it "invoked neither the names nor the rhetoric of Spencer or Darwin." | ” |

Another example of Darwinist influence in Sumner’s work was his analysis of warfare in one of his essays in the 1880s. Contrary to some beliefs, Sumner did not believe that warfare was a result of primitive societies; he suggested that “real warfare” came from more developed societies. It was believed that primitive cultures would have war as a “struggle for existence”, but Sumner believed that war in fact came from a “competition for life”. Although war was sometimes man against nature, fighting another tribe for their resources, it was more often a conflict between man and man. For example one man fighting against another man because of his ideologies. Sumner explained that the competition for life was the reason for war and that is why war has always existed and always will.

Sumner's most popular book is Folkways: A study of the sociological importance of usages, manners, customs, mores, and morals (1907). Starting with four theoretical chapters, it provides a frank,

objective and candid description of the nature of many of the more

important customs and institutions in societies past and present around

the world. The book promotes a sociological or relativistic approach to

moral behavior, as expressed in his thesis that "the mores can make

anything right and prevent condemnation of anything."

Graham argued that in his day, politics was being subverted by those proposing "measure of relief for the evils which have caught public attention." He wrote,

Sumner's popular essays gave him a wide audience for his laissez - faire advocacy of free markets, anti - imperialism, and the gold standard. Thousands of Yale students took his courses and many remarked on his influence. His essays were very widely read among intellectuals and men of affairs. Among Sumner's students were the anthropologist Albert Galloway Keller, the economist Irving Fisher and the champion of an anthropological approach to economics, Thorstein Bunde Veblen.As soon as A observes something which seems to him wrong, from which X is suffering, A talks it over with B, and A and B then propose to get a law passed to remedy the evil and help X. Their law always proposes to determine what C shall do for X, or, in better case, what A, B and C shall do for X... What I want to do is to look up C... I call him the forgotten man... He is the man who never is thought of. He is the victim of the reformer, the social speculator, and philanthropist, and I hope to show you before I get through that he deserves your notice both for his character and for the many burdens which are laid upon him.—Summer, The Forgotten Man and Other Essays