<Back to Index>

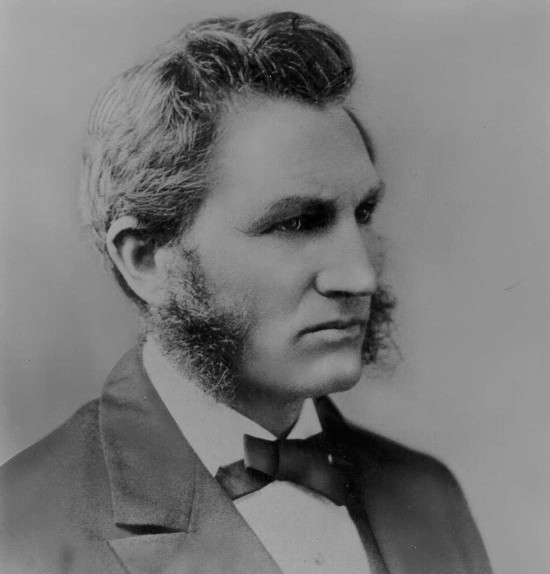

- Botanist, Paleontologist and Sociologist Lester Frank Ward, 1841

- Engineer, Economist and Sociologist Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto, 1848

PAGE SPONSOR

Lester F. Ward (June 18, 1841 – April 18, 1913) was an American botanist, paleontologist and sociologist. He served as the first president of the American Sociological Association.

Lester Frank Ward was born in Joliet, Illinois,

the youngest of 10 children born to Justus Ward and his wife Silence

Rolph Ward. Justus Ward was of old New England colonial stock, but he

was not rich and farmed to earn a living. Silence Ward was the daughter

of a clergyman; she was a talented perfectionist, educated and fond of

literature. When Lester Frank was one year of age the family moved

closer to Chicago, to a place called Cass, now known as Downer's Grove, Illinois, about twenty three miles from Lake Michigan. The family then moved to a homestead in nearby St. Charles, Illinois,

where his father built a saw mill business making railroad ties. Ward

first attended a formal school in 1850 when he was nine years old. He

was known as Frank Ward to his classmates and friends and showed a great

enthusiasm for books and learning and he liberally supplemented his

education with outside reading. 4 years after Ward started attending

school, his parents, Lester Frank and one of his older bothers, Erastus,

traveled to Iowa in a covered wagon for a new life on the frontier.

Four years later, in 1858, Justus Ward unexpectedly died and the family

returned to St. Charles, much to the dismay of Ward's mother who wanted

the boys to stay in Iowa and continue their father's work. The two

brothers lived together for a sort period of time in the old family

homestead in St. Charles, doing farm work to earn a living, and

encouraged each other to pursue an education and abandon their father's

life of physical labor. Their estranged mother lived just down the

street in the home of one of their sisters.

In late 1858 the two brothers moved to Pennsylvania at the invitation of Lester Frank's oldest brother Cyrenus (9 years Lester Frank's senior) who was starting a business making wagon wheel hubs and needed workers. The brothers saw this as an opportunity to move closer to civilization and to eventually attend college. The business failed, however, and Lester Frank, who still did not have the money to attend college, found a job teaching in a small country school; in the Summer months he worked as a farm laborer. He finally saved the money to attend college and enrolled in the Susquehanna Collegiate Institute in 1860. While he was at first self conscious about his spotty formal education and self learning, he soon found that his knowledge compared favorably to his classmates, and he was rapidly promoted. It was here that he met Elizabeth "Lizzie" Carolyn Vought and fell deeply in love. (Their rather torrid love affair is documented in Ward's first journal: "Young Ward's Diary", which remains under copyright and in print.) He married Lizzie on Aug. 13, 1862 and almost immediately enlisted in the Union Army and was sent to the Civil War front where he was wounded three times. After the end of the war he successfully petitioned for work with the federal government in Washington, DC, where he and Lizzie then moved. Lizzie assisted him in editing a newsletter called "The Iconoclast", dedicated to free thinking. She gave birth to a son, but the child died when he was less than a year old. Then, in 1872, Lizzie became ill and died. These were hard times for Ward to live through.

After moving to Washington, Ward attended Columbian College, now the George Washington University, and graduating in 1869 with the degree of A.B.. In 1871 he received the degree of LL.B. (and was admitted to the Bar of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia), and that of A.M.

in 1873. Ward never practiced law, however, and concentrated on his

carrier in the federal government. Almost all of the basic research in

such fields as geography, paleontology, archeology and anthropology were

concentrated in Washington, DC. at this time in history, and a job as a

federal government scientist was a prestigious and influential

position. In 1883 he was made Geologist of the U.S. Geological Survey.

In 1895, he was made Paleontologist. He held this position until 1906,

when he resigned to accept the chair of Sociology at Brown University.

While he worked at the Geological Survey he became good friends with

John Wesley Powell, the powerful and influential second director of the US Geological Survey (1881 – 1894) and the director of the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution.

By the early 1880s the new field of sociology had become dominated by ideologues of the left and right, both determined to claim "the science of society" as their own. The champion of the conservatives and businessmen was Herbert Spencer; he was opposed on the left by Karl Marx. Although Spencer and Marx disagreed about many things they were similar in that their systems were static: they both claimed to have divined the immutable stages of development that a society went through and they both taught that mankind was essentially helpless before the force of evolution.

With the publication of the two volume, 1200 page, Dynamic Sociology -- Or Applied Social Science as Based Upon Statical Sociology and the Less Complex Sciences (1883), Lester Ward hoped to restore the central importance of experimentation and the scientific method to the field of sociology. For Ward science wasn't cold or impersonal, it was human centered and results oriented. As he put it in the Preface to Dynamic Sociology: "The real object of science is to benefit man. A science which fails to do this, however agreeable its study, is lifeless. Sociology, which of all sciences should benefit man most, is in danger of falling into the class of polite amusements, or dead sciences. It is the object of this work to point out a method by which the breath of life may be breathed into its nostrils."

Ward theorized that poverty could be minimized or eliminated by the systematic intervention of society. Mankind was not helpless before the impersonal force of nature and evolution – through the power of Mind, man could take control of the situation and direct the evolution of human society. This theory is known as telesis (see, also, meliorism, sociocracy and public sociology). A sociology which intelligently and scientifically directed the social and economic development of society should institute a universal and comprehensive system of education, regulate competition, connect the people together on the basis of equal opportunities and cooperation, and promote the happiness and the freedom of everyone.

Ward is most often remembered for his relentless attack on Herbert Spencer and his theories of laissez faire and survival of the fittest that totally dominated socioeconomic thought in the United States after the Civil War. While Marx and communism / socialism did not catch on in the United States during Ward's lifetime, Spencer became famous: he was the leading light for conservatives. Ward placed himself in direct opposition to Spencer and Spencer's American disciple, William Graham Sumner, who had become the most well known and widely read American sociologist by single - mindedly promoting the principles of laissez faire. To quote the historian Henry Steele Commager: "Ward was the first major scholar to attack this whole system of negativist and absolutist sociology and he remains the ablest.... Before Ward could begin to formulate that science of society which he hoped would inaugurate an era of such progress as the world had not yet seen, he had to destroy the superstitions that still held domain over the mind of his generation. Of these, laissez faire was the most stupefying, and it was on the doctrine of laissez faire that he trained his heaviest guns. The work of demolition performed in Dynamic Sociology, Psychic Factors and Applied Sociology was thorough."

Ward was a strong advocate for equal rights for women and even theorized that women were naturally superior to men, much to the scorn of mainstream sociologists. In this regard, Ward presaged the rise of feminism, and especially the difference feminism of writers such as Harvard's Carol Gilligan, who have developed the claims of female superiority. Ward is now considered a feminist writer by historians such as Ann Taylor Allen. Ward's persuasion on the question of female intelligence as described by himself: "And now from the point of view of intellectual development itself we find her side by side, and shoulder to shoulder with him furnishing, from the very outset, far back in prehistoric, presocial, and even prehuman times, the necessary complement to his otherwise one sided, headlong, and wayward career, without which he would soon have warped and distorted the race and rendered it incapable of the very progress which he claims exclusively to inspire. And herefore again, even in the realm of intellect, where he would fain reign supreme, she has proved herself fully his equal and is entitled to her share of whatever credit attaches to human progress hereby achieved."

Ward had a considerable influence on the United States' environmental policy in the late 19th and early 20th century. Ross listed Ward among the four "philosopher / scientists" that shaped American early environmental policies.

Ward's views on the question of race and the theory of white supremacy underwent considerable change throughout his life. Ward was a Republican Whig and supported the abolition of the American system of slavery. He enlisted in the Union army during the Civil war and was wounded three times. However, a close reading of "Dynamic Sociology" will uncover several statements that would be considered racist and ethnocentric by today's standards. There are references to the superiority of Western culture and the savagery of the American Indian and black races, made all the more jarring by the modern feel of much of the rest of the book. However, Ward lived in Washington D.C., then the center of anthropological research in the US; he was always up - to - date on the latest findings of science and in tune with the developing zeitgeist, and by the early twentieth century, perhaps influenced by W. E. B. Du Bois and Franz Boas he began to focus more on the question of race. During this period his views on race were arguably more progressive and in tune with modern standards than any other white academic of the time, with, of course, the exception of Boas, who is sometimes credited with doing more than any other American in combating the theory of White supremacy. Ward, given his age and reputation, could afford to take a somewhat radical stand on the politically explosive question of White supremacy, but Boas did not have those advantages. After Ward's death in 1913 and with the approach of World War I the German born Boas came to be seen by some, including W. H. Holmes, the head of National Research Council (and who had worked with Ward for many years at the U.S. Geological Survey), as possibly being an agent of the German government determined to sow revolution in the US and among its troops. The NRC had been set up by the Wilson administration in 1916 in response to the increased need for scientific and technical services caused by World War I, and soon Boas's influence over the field of anthropology in the US began to wane. By 1919 he was censured by the American Anthropological Association for his political activities, a censure which would not be lifted until 2005 (see, also, Scientific racism, Master race, and Institutional racism).

Ward is often categorized as been a follower of Jean - Baptiste Lamarck. Ward's article "Neo - Darwinism and Neo - Lamarckism" shows Ward had a sophisticated understanding of this subject. While he clearly described himself as being a Neo - Lamarckian, he completely and enthusiastically accepted Darwin's findings and theories. On the other hand, he believed that, logically, there had to be a mechanism that would allow environmental factors to influence evolution faster than Darwin's rather slow evolutionary process. The modern theory of Epigenetics suggests that Ward was correct on this issue, although old school Darwinians continue to ridicule Larmarkianism.

While Durkheim is usually credited for updating Comte's positivism to modern scientific and sociological standards, Ward accomplished much the same thing 10 years earlier in the United States. However, Ward would be the last person to claim that his contributions were somehow unique or original to him. As Gillis J. Harp points out in "The Positivist Republic", Comte's positivism found a fertile ground in the democratic republic of the United States, and there soon developed among the pragmatic intellectual community in New York City, which featured such thinkers as William James and Charles Sanders Peirce and, on the other hand, among the federal government scientists in Washington D.C. (like Ward) a general consensus regarding positivism.

Despite Ward's impressive and ground breaking accomplishments he has been largely written out of the history of sociology. Why? Paradoxically the thing that made Ward most attractive in the 19th century, his criticism of lassiez faire, made him seem dangerously radical to the ever cautious academic community in early 20th century America. This perception was strengthened by the growing socialist movement in the US, led by Eugene V. Debs, the Marxist Russian Revolution, and the rise of Nazism in Europe. Ward was basically just replaced by Durkheim in the history books, which was easily accomplished because Durkheim's views were similar to Ward's but without the relentless criticism of lassiez faire and without Ward's calls for a strong central government and "social engineering". In 1937 Talcott Parsons, the Harvard sociologist and functionalist who almost single handedly set American sociology's academic curriculum in the mid 20th century, wrote that "Spencer is dead", thereby dismissing not only Spencer but also Spencer's most powerful critic.

It would be interesting to know Ward's candid views on the controversial

political subjects and the people of the time (and that he was

interested in these topics can be seen in the rather odd introduction to

the second edition of "Dynamic Sociology" were he talks at length about

the situation in pre - revolutionary Russia and jokes about Dynamic

Sociology being mistranslated as "Dynamite Socialism"). However, all but

the first of his voluminous journals were reportedly destroyed by his

wife after his death. Ward's first journal, "Young Ward's diary: A human

and eager record of the years between 1860 and 1870...", remains under

copyright and one could always hope that more of his writings may

reappear at some future date.

Ward had strong influence on a rising generation of progressive political leaders, such as Herbert Croly. In the book "Lester Ward and the Welfare State", Commager details Ward's influence and refers to him as the "father of the modern welfare state".

As a political approach, Ward's system became known as social liberalism, as distinguished from the classical liberalism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries which featured such thinkers as Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill. While classical liberalism had sought prosperity and progress through laissez fare, Ward's "American social liberalism" sought to enhance social progress through direct government intervention. Ward believed that in large, complex and rapidly growing societies human freedom could only be achieved with the assistance of a strong democratic government acting in the interest of the individual. The characteristic element of Ward's thinking was his faith that government, acting on the empirical and scientifically based findings of the science of sociology, could be harnessed to create a near Utopian social order.

Ward's thinking had a profound impact on the administrations of Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson and Franklin D. Roosevelt and on the modern Democratic Party. The "liberalism" of the Democrats today is not that of Smith and Mill, which stressed non - interference from the government in economic issues, but of Ward, which stressed the unique position of government to effect positive change. While Roosevelt's experiments in social engineering were popular and effective, the full effect of the forces Ward set in motion came to bear half a century after his death, in the Great Society programs of President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Vietnam war.

Ward realized that the path to human progress was not easy or smooth. His hope was that the "science" of sociology, which was but in its infancy, would allow government officials to learn from their past mistakes.

Ward died in Washington, D.C.. He is buried in Watertown, New York.

"In many respects the botanist looks at the world from a point of view precisely the reverse of that of other people. Rich fields of corn are to him waste lands; cities are his abhorrence, and great open areas under high cultivation he calls 'poor country'; while on the other hand the impenetrable forest delights his gaze, the rocky cliff charms him, thin - soiled barrens, boggy fens, and unreclaimable swamps and morasses are for him the finest land in a State. He takes no delight in the 'march of civilization,' the ax and the plow are to him symbols of barbarism, and the reclaiming of waste lands and opening up of his favorite haunts to civilization he instinctively denounces as acts of vandalism." -- Lester Ward

"Every implement or utensil, every mechanical device... is a triumph of mind over the physical forces of nature in ceaseless and aimless competition. All human institutions — religion, government, law, marriage, custom — together with innumerable other modes of regulating social, industrial and commercial life are, broadly viewed, only so many ways of meeting and checkmating the principle of competition as it manifests itself in society." -- Lester Ward

"Thus far, social progress has in a certain awkward manner taken care of itself, but in the near future it will have to be cared for. To do this, and maintain the dynamic condition against all the hostile forces which thicken with every new advance, is the real problem of sociology considered as an applied science" -- Lester Ward

"To overcome [the] manifold hindrances to human progress, to check this enormous waste of resources, to calm these rhythmic billows of hyper - action and reaction, to secure the rational adaptation of means to remote ends, to prevent the natural forces from clashing with the human feelings, to make the current of physical phenomena flow in the channels of human advantage - these are some of the tasks which belong to the great art which forms the final or active department of the science of society - this, in brief, is DYNAMIC SOCIOLOGY. “Voir pour prévoir"; "prévoyance, d'où action," i.e., predict in order to control, such is the logical history and process of all science; and, if sociology is a science, such must be its destiny and its legitimate function." -- Lester Ward

"Again, society desires most the education of those most needing to be educated. From an economical point of view, an uneducated class is an expensive class. It is from it that most criminals, drones and paupers come. From it — and this is still more important — no progressive actions ever flow. Therefore, society is most anxious that this class, which would never educate itself, should be educated... The secret of the superiority of state over private education lies in the fact that in the former the teacher is responsible to society ... [T]he result desired by the state is a wholly different one from that desired by parents, guardians, and pupils." -- Lester Ward

"And now, mark : The charge of paternalism is chiefly made by the class that enjoys the largest share of government protection. Those who denounce state interference are the ones who most frequently and successfully invoke it. The cry of laissez faire mainly goes up from the ones who, if really "let alone," would instantly lose their wealth - absorbing power.... Nothing is more obvious to-day than the signal inability of capital and private enterprise to take care of themselves unaided by the state; and while they are incessantly denouncing "paternalism," by which they mean the claim of the defenseless laborer and artisan to a share in this lavish state protection, they are all the while besieging legislatures for relief from their own incompetency, and "pleading the baby act" through a trained body of lawyers and lobbyists. The dispensing of national pap to this class should rather be called "maternalism," to which a square, open and dignified paternalism would be infinitely preferable." -- Lester Ward

"When a well clothed philosopher on a bitter winter’s night sits in a warm room well lighted for his purpose and writes on paper with pen and ink in the arbitrary characters of a highly developed language the statement that civilization is the result of natural laws, and that man’s duty is to let nature alone so that untrammeled it may work out a higher civilization, he simply ignores every circumstance of his existence and deliberately closes his eyes to every fact within the range of his faculties. If man had acted upon his theory there would have been no civilization, and our philosopher would have remained a troglodyte." -- Lester Ward

"In perspicacity, intellectual acumen, and imagination, he [Lester

Ward] was the equal of Henry Adams or Thorstein Velben or Louis

Sullivan, but he was better rounded and more constructive than these

major critics. In the rugged vigor of his mind, the richness of his

learning, the originality of his insights, the breath of his

conceptions, he takes place alongside William James, John Dewey and

Oliver Wendell Holmes as one of the creative spirits of

Twentieth century America." -- Henry Steele Commager

Vilfredo Federico Damaso Pareto (15 July 1848 – 19 August 1923), born Wilfried Fritz Pareto, was an Italian engineer, sociologist, economist, political scientist and philosopher. He made several important contributions to economics, particularly in the study of income distribution and in the analysis of individuals' choices.

He introduced the concept of Pareto efficiency and helped develop the field of microeconomics. He also was the first to discover that income follows a Pareto distribution, which is a power law probability distribution. The Pareto principle was named after him and built on observations of his such as that 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. He also contributed to the fields of sociology and mathematics.

Pareto was born of an exiled noble Genoese family in 1848 in Paris, the center of the popular revolutions of that year. His father, Raffaele Pareto (1812 – 1882), was an Italian civil engineer and Ligurian marchese who had left Italy much like Mazzini and other Italian nationalists. His mother, Marie Metenier, was a French woman. Enthusiastic about the 1848 German revolution, his parents named him Fritz Wilfried, which became Vilfredo Federico upon his family's move back to Italy in 1858. In his childhood, Pareto lived in a middle class environment, receiving a high standard of education. In 1870, he earned a degree in engineering from what is now the Polytechnic University of Turin. His dissertation was entitled "The Fundamental Principles of Equilibrium in Solid Bodies". His later interest in equilibrium analysis in economics and sociology can be traced back to this paper."His legacy as an economist was profound. Partly because of him, the field evolved from a branch of moral philosophy as practiced by Adam Smith into a data intensive field of scientific research and mathematical equations. His books look more like modern economics than most other texts of that day: tables of statistics from across the world and ages, rows of integral signs and equations, intricate charts and graphs."

For some years after graduation, he worked as a civil engineer, first for the state owned Italian Railway Company and later in private industry. He did not begin serious work in economics until his mid forties. He started his career a fiery liberal, besting the most ardent British liberals with his attacks on any form of government intervention in the free market. In 1886 he became a lecturer on economics and management at the University of Florence. His stay in Florence was marked by political activity, much of it fueled by his own frustrations with government regulators. In 1889, after the death of his parents, Pareto changed his lifestyle, quitting his job and marrying a Russian, Alessandrina Bakunin. She later left him for a young servant.

In 1893, he was appointed a lecturer in economics at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland where he remained for the rest of his life. In 1906, he made the famous observation that twenty percent of the population owned eighty percent of the property in Italy, later generalized by Joseph M. Juran into the Pareto principle (also termed the 80-20 rule). In one of his books published in 1909 he showed the Pareto distribution of how wealth is distributed, he believed "through any human society, in any age, or country". He maintained cordial personal relationships with individual socialists, but always thought their economic ideas were severely flawed. He later became suspicious of their humanitarian motives and denounced socialist leaders as an 'aristocracy of brigands' who threatened to despoil the country and criticized the government of Giovanni Giolitti for not taking a tougher stance against worker strikes. Growing unrest among labor in Italy led him to the anti - socialist and anti - democratic camp. His attitude toward fascism in his last years is a matter of controversy.

In the 1920s Pareto remarried. He died in Geneva, Switzerland, 19 August 1923, "among a menagerie of cats that he and his french lover kept" in their villa; "the local divorce laws prevented him from divorcing his wife and remarrying until just a few months before his death."

Pareto's later years were spent in collecting the material for his best known work, Trattato di sociologia generale (1916) ("The Mind and Society" (1935)). His final work was Compendio di sociologia generale (1920).

In his Trattato di Sociologia Generale (1916, rev. French trans. 1917), published in English by Harcourt, Brace in a four volume edition edited by Arthur Livingston under the title The Mind and Society (1935), Pareto put forward the first social cycle theory in sociology. He is famous for saying "history is a graveyard of aristocracies."

Pareto seems to have turned to sociology for an understanding of why his abstract mathematical economic theories did not work out in practice, in the belief that unforeseen or uncontrollable social factors intervened. His sociology holds that much social action is nonlogical and that much personal action is designed to give nonrational actions to spurious logicality. We are driven, he taught, by certain "residues" and by "derivations" from these residues. The more important of these have to do with conservatism and risk taking, and human history is the story of the alternate dominance of these sentiments in the ruling elite, which comes into power strong in conservatism but gradually changes over to the philosophy of the "foxes" or speculators. A catastrophe results, with a return to conservatism; the "lion" mentality follows. This cycle might be broken by the use of force, says Pareto, but the elite becomes weak and humanitarian and shrinks from violence.

Pareto's sociology was introduced to the United States by George

Homans and Lawrence J. Henderson at Harvard, and had considerable

influence, especially on Harvard sociologist Talcott Parsons, who

developed a systems approach to society and economics that argues the

status quo is usually functional.

Benoît Mandelbrot writes:

"One of Pareto's equations achieved special prominence, and controversy. He was fascinated by problems of power and wealth. How do people get it? How is it distributed around society? How do those who have it use it? The gulf between rich and poor has always been part of the human condition, but Pareto resolved to measure it. He gathered reams of data on wealth and income through different centuries, through different countries: the tax records of Basel, Switzerland, from 1454 and from Augsburg, Germany in 1471, 1498 and 1512; contemporary rental income from Paris; personal income from Britain, Prussia, Saxony, Ireland, Italy, Peru. What he found – or thought he found – was striking. When he plotted the data on graph paper, with income on one axis, and number of people with that income on the other, he saw the same picture nearly everywhere in every era. Society was not a "social pyramid" with the proportion of rich to poor sloping gently from one class to the next. Instead it was more of a "social arrow" – very fat on the bottom where the mass of men live, and very thin at the top where sit the wealthy elite. Nor was this effect by chance; the data did not remotely fit a bell curve, as one would expect if wealth were distributed randomly. "It is a social law," he wrote: something "in the nature of man".

Pareto's discovery that power laws applied to income distribution embroiled him in political change and the nascent Fascist movement, whether he really sided with the Fascists or not. Fascists such as Mussolini found inspiration for their own economic ideas in his discoveries. He had discovered something that was harsh and Darwinian, in Pareto's view. And this fueled both the anger and the energy of the Fascist movement because it fueled their economic and social views. He wrote that, as Mandelbrot summarizes:

"At the bottom of the Wealth curve, he wrote, Men and Women starve and children die young. In the broad middle of the curve all is turmoil and motion: people rising and falling, climbing by talent or luck and falling by alcoholism, tuberculosis and other kinds of unfitness. At the very top sit the elite of the elite, who control wealth and power for a time – until they are unseated through revolution or upheaval by a new aristocratic class. There is no progress in human history. Democracy is a fraud. Human nature is primitive, emotional, unyielding. The smarter, abler, stronger, and shrewder take the lion's share. The weak starve, lest society become degenerate: One can, Pareto wrote, 'compare the social body to the human body, which will promptly perish if prevented from eliminating toxins.' Inflammatory stuff – and it burned Pareto's reputation."

Pareto had argued that democracy was an illusion and that a ruling class always emerged and enriched itself. For him, the key question was how actively the rulers ruled. For this reason he called for a drastic reduction of the state and welcomed Benito Mussolini's rule as a transition to this minimal state so as to liberate the "pure" economic forces.

To quote Pareto's biographer:

"In the first years of his rule Mussolini literally executed the policy prescribed by Pareto, destroying political liberalism, but at the same time largely replacing state management of private enterprise, diminishing taxes on property, favoring industrial development, imposing a religious education in dogmas".

Karl Popper dubbed him the "theoretician of totalitarianism," but there is no evidence in Popper's published work that he read Pareto in any detail before repeating what was then a common but dubious judgment in anti - fascist circles.

It is true that Pareto regarded Mussolini's triumph as a confirmation of certain of his ideas, largely because Mussolini demonstrated the importance of force and shared his contempt for bourgeois parliamentarism. He accepted a "royal" nomination to the Italian senate from Mussolini. But he died less than a year into the new regime's existence.

Some fascist writers were much enamored of Pareto, writing such paeans as:

"Just as the weaknesses of the flesh delayed, but could not prevent, the triumph of Saint Augustine, so a rationalistic vocation retarded but did not impede the flowering of the mysticism of Pareto. For that reason, Fascism, having become victorious, extolled him in life, and glorifies his memory, like that of a confessor of its faith."

On being sent an anti - Semitic book, Pareto's reply indicated no repulsion for it.

But many modern historians reject the notion that Pareto's thought was

essentially fascistic or that he is properly regarded as a supporter of

fascism.

Pareto turned his interest to economic matters and he became an advocate of free trade, finding himself in difficulty with the Italian government. His writings reflected the ideas of Leon Walras that economics is essentially a mathematical science. Pareto was a leader of the "Lausanne School" and represents the second generation of the Neoclassical revolution. His "tastes - and - obstacles" approach to general equilibrium theory were resurrected during the great "Paretian Revival" of the 1930s and have influenced theoretical economics since.

In his Manual of Political Economy (1906) the focus is on equilibrium in terms of solutions to individual problems of "objectives and constraints". He used the indifference curve of Edgeworth (1881) extensively, for the theory of the consumer and, another great novelty, in his theory of the producer. He gave the first presentation of the tradeoff box now known as the "Edgeworth - Bowley" box.

Pareto realized that cardinal utility could be dispensed with — that

is, it was not necessary to know how much a person valued this or that,

only that he preferred X of this to Y of that. Utility was a

preference ordering. With this, Pareto not only inaugurated modern

microeconomics, but he also demolished the alliance of economics and

utilitarian philosophy (which calls for the greatest good for the

greatest number; Pareto said "good" cannot be measured). He replaced it

with the notion of Pareto - optimality, the idea that a system is

enjoying maximum economic satisfaction when no one can be made better

off without making someone else worse off. Pareto optimality is widely

used in welfare economics and game theory. A standard theorem is that a

perfectly competitive market creates distributions of wealth that are

Pareto optimal.

Some economic concepts in current use are based on his work:

- The Pareto index is a measure of the inequality of income distribution.

He argued that in all countries and times, the distribution of income and wealth is highly skewed, with a few holding most of the wealth. He argued that all observed societies follow a regular logarithmic pattern:

- log N = log A + m log x

where N is the number of people with wealth higher than x, and A and m are constants. Over the years, Pareto's Law has proved remarkably close to observed data.

- The Pareto chart is a special type of histogram, used to view causes of a problem in order of severity from largest to smallest. It is a statistical tool that graphically demonstrates the Pareto principle or the 80-20 rule.

- Pareto's law concerns the distribution of income.

- The Pareto distribution is a probability distribution used, among other things, as a mathematical realization of Pareto's law.

- Ophelimity is a measure of purely economic satisfaction.