<Back to Index>

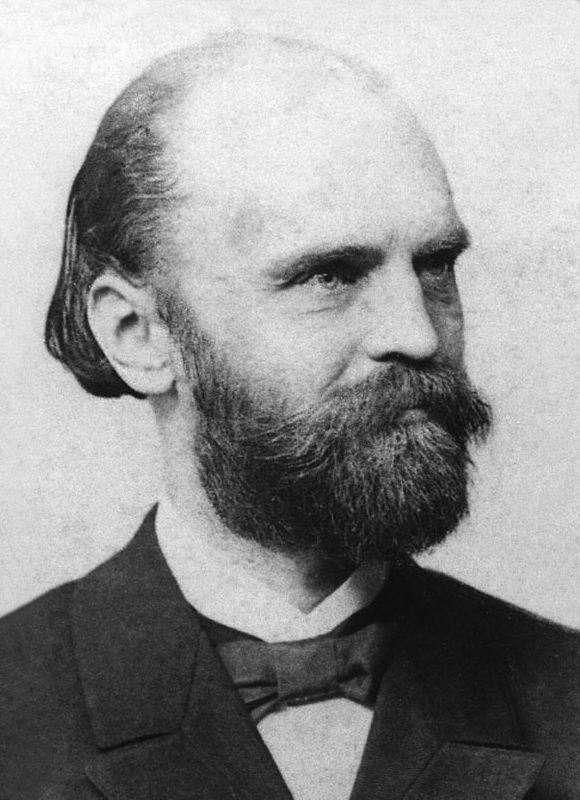

- Sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies, 1855

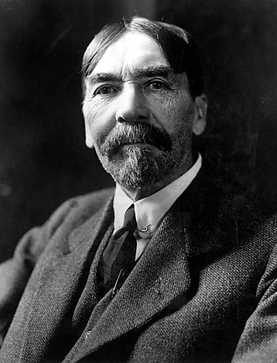

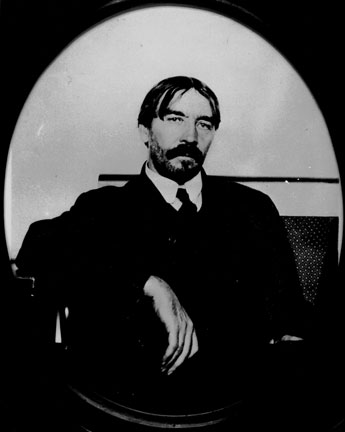

- Economist and Sociologist Thorstein Bunde Veblen, 1857

PAGE SPONSOR

Ferdinand Tönnies (26 July 1855, near Oldenswort (Eiderstedt, North Frisia, Schleswig) - 9 April 1936, Kiel, Germany) was a German sociologist. He was a major contributor to sociological theory and field studies, best known for his distinction between two types of social groups, Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft. He was also a prolific writer and co-founder of the German Society for Sociology (of which he was president from 1909 to 1933, when he was ousted by the Nazis).

Ferdinand Tönnies was born into a wealthy farmer's family in North Frisia, Schleswig (today Nordfriesland, Schleswig - Holstein), then under Danish rule. He studied at the universities of Jena, Bonn, Leipzig, Berlin and Tübingen. He received a doctorate in Tübingen in 1877 (with a Latin thesis on the ancient Siwa Oasis). Four years later he became a private lecturer at the University of Kiel. Because he had sympathized with the Hamburg dockers' strike of 1896, the conservative Prussian government considered him to be a social democrat, and Tönnies was not called to a professorial chair until 1913. He held this post at the University of Kiel for only three years. He returned to the university as a professor emeritus in 1921 and taught until 1933 when he was ousted by the Nazis, due to his earlier publications that criticized them.

Tönnies, the first German sociologist proper,

published over 900 works and contributed to many areas of sociology and

philosophy. Many of his writings on sociological theories — including Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887) — furthered pure sociology. He coined the metaphysical term Voluntarism. Tönnies also contributed to the study of social change, particularly on public opinion,

customs and technology, crime, and suicide. He also had a vivid

interest in methodology, especially statistics, and sociological

research, inventing his own technique of statistical association.

Tönnies distinguished between two types of social groupings. Gemeinschaft — often translated as community (or left untranslated) — refers to groupings based on feelings of togetherness and on mutual bonds, which are felt as a goal to be kept up, their members being means for this goal. Gesellschaft — often translated as society — on the other hand, refers to groups that are sustained by it being instrumental for their members' individual aims and goals.

Gemeinschaft may be exemplified historically by a family or a neighborhood in a pre - modern (rural) society; Gesellschaft by a joint stock company or a state in a modern society, i.e., the society when Tönnies lived. Gesellschaft relationships arose in an urban and capitalist setting, characterized by individualism and impersonal monetary connections between people. Social ties were often instrumental and superficial, with self interest and exploitation increasingly the norm. Examples are corporations, states or voluntary associations.

His distinction between social groupings is based on the assumption that there are only two basic forms of an actor's will, to approve of other men. (For Tönnies, such an approval is by no means self evident, he is quite influenced by Thomas Hobbes). Following his "essential will" ("Wesenwille"), an actor will see himself as a means to serve the goals of social grouping; very often it is an underlying, subconscious force. Groupings formed around an essential will are called a Gemeinschaft. The other will is the "arbitrary will" ("Kürwille"): An actor sees a social grouping as a means to further his individual goals; so it is purposive and future oriented. Groupings around the latter are called Gesellschaft. Whereas the membership in a Gemeinschaft is self fulfilling, a Gesellschaft is instrumental for its members. In pure sociology — theoretically —, these two normal types of will are to be strictly separated; in applied sociology — empirically — they are always mixed.

Tönnies’ distinction between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft, like others between tradition and modernity, has been criticized for over - generalizing differences between societies, and implying that all societies were following a similar evolutionary path, which he has never proclaimed.

The equilibrium in Gemeinschaft is achieved through morals,

conformism, and exclusion - social control - while Gesellschaft keeps

its equilibrium through police, laws, tribunals and prisons. Amish,

Hassidic communities are examples of Gemeinschaft, while states are

types of Gesellschaft. Rules in Gemeinschaft are implicit, while

Gesellschaft has explicit rules (written laws).

Thorstein Bunde Veblen, born Torsten Bunde Veblen (July 30, 1857 – August 3, 1929) was an American economist and sociologist, and a leader of the institutional economics movement. Besides his technical work he was a popular and witty critic of capitalism, as shown by his best known book The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899).

Veblen is famous in the history of economic thought for combining a Darwinian evolutionary perspective with his new institutionalist approach to economic analysis. He combined sociology with economics in his masterpiece, The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), arguing there was a basic distinction between the productiveness of "industry," run by engineers, which manufactures goods, and the parasitism of "business," which exists only to make profits for a leisure class. The chief activity of the leisure class was "conspicuous consumption", and their economic contribution is "waste," activity that contributes nothing to productivity. The American economy was therefore made inefficient and corrupt by the businessmen, though he never made that claim explicit. Veblen believed that technological advances were the driving force behind cultural change, but, unlike many contemporaries, he refused to connect change with progress.

Although Veblen was sympathetic to state ownership

of industry, he had a low opinion of workers and the labor movement and

there is disagreement about the extent to which his views are

compatible with Marxism. As a leading intellectual of the Progressive Era,

his sweeping attack on production for profit and his stress on the

wasteful role of consumption for status greatly influenced socialist

thinkers and engineers who sought a non - Marxist critique of capitalism.

Fine (1994) reports that economists at the time complained that his

ideas, while brilliantly presented, were crude, gross, fuzzy and

imprecise; others complained he was a wacky eccentric. Scholars continue

to debate exactly what he meant in his convoluted, ironic and satiric

essays; he made heavy use of examples of primitive societies, but many

examples were pure invention.

Veblen was born in Cato, Wisconsin, of Norwegian American parents who had immigrated from Norway. He spent the majority of his youth on his family farm in Nerstrand, Minnesota; the farmstead is now a National Historic Landmark. Although Norwegian was his first language, he learned English from both neighbors and at school, which he began at the age of 5. His family was highly successful and placed great emphasis on education and hard work, all of which undoubtedly contributed to his later scorn for what he termed “conspicuous consumption” and waste of the gilded age. These settlements were little Norways, oriented around the religious and cultural traditions of the old country . He broke away by attending a Yankee school, Carleton College Academy (now Carleton College) in Northfield, Minnesota; he was lucky to study with young John Bates Clark (1847 – 1938), who later became the nation's foremost economist and was a leader in the new field of neoclassical economics.

Veblen did graduate work at Johns Hopkins University under Charles Sanders Peirce, the founder of the pragmatist school in philosophy; he took his Ph.D. in 1884 at Yale University with a dissertation on "Ethical Grounds of a Doctrine of Retribution." He was a student of philosopher Noah Porter (1811 – 1892) and economist / sociologist William Graham Sumner (1840 – 1910). Perhaps the most important intellectual influences on Veblen were Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer, whose work in the last half of the 19th century sparked an enormous interest in the evolutionary perspective on human societies.

Veblen married fellow Cornellian Ellen Rolfe in 1888; it was a very unhappy marriage that finally ended in divorce in 1911.

He married secondly, Ann Bradley, in 1914. Veblen became the step

father to her two girls, Becky and Ann. After his wife's death in 1920,

Veblen became very active in the care of the girls. Becky went with him

when he moved to California, and looked after him there. She was with

him at his death in 1929.

Upon graduation from Yale, Veblen was unable to obtain an academic job, partly due to prejudice against Norwegians, and partly because most universities considered him insufficiently educated in Christianity — most academics at the time held divinity degrees. Veblen returned to his family farm — ostensibly to recover from malaria — and spent six years there reading voraciously. In 1891 he left the farm, to study economics as a graduate student at Cornell University under James Laurence Laughlin.

He obtained his first academic appointment at the new University of Chicago, which overnight had become a world class university in many fields. He was promoted to assistant professor in 1900 and edited the prestigious Journal of Political Economy, while conversing with such intellectuals as John Dewey, Jane Addams and Franz Boas. He published two of his best known books, The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), and The Theory of Business Enterprise (1904). The books made him famous overnight for their ridicule of businessmen. In 1906, he moved to Stanford University. He soon left, perhaps because of adultery, or because the faculty and administration distrusted a man they saw as a poor teacher, a nasty colleague and a political radical.

Veblen reflected many of his views in his personal habits. Veblen's house was often a mess, with unmade beds and dirty dishes; his clothes were often in disarray; he was an agnostic; and he tended to be blunt and rude while dealing with other people.

In 1911, Veblen joined the faculty of the University of Missouri, where he had support from Herbert Davenport, the head of the economics department. Veblen disliked the local town but remained until in 1918 he moved to New York to begin work as an editor of The Dial. In 1919, along with Charles A. Beard, James Harvey Robinson and John Dewey, he helped found the New School for Social Research (known today as The New School). From 1919 through 1926 Veblen continued to write and be involved in activities at The New School. The Engineers and the Price System was written during this period.

Veblen proposed a soviet of engineers in one chapter in The Engineers and the Price System. According to Yngve Ramstad, this work's view that engineers, not workers, would overthrow capitalism was a "novel view". Veblen invited Guido Marx to the New School to teach and to help organize a movement of engineers, by such as Morris Cooke; Henry Laurence Gantt, who had died shortly before; and Howard Scott. Cooke and Gantt were followers of Taylor's Scientific Management. Scott, who listed Veblen as on the temporary organizing committee of the Technical Alliance, perhaps without consulting Veblen or other listed members, later helped found the Technocracy movement. Veblen had a penchant for socialism and believed that technological developments would eventually lead toward a socialistic organization of economic affairs. However, his views regarding socialism and the nature of the evolutionary process of economics differed sharply from that of Karl Marx; while Marx saw socialism as the ultimate goal for civilization and saw the working class as the group that would establish it, Veblen saw socialism as one intermediate phase in an ongoing evolutionary process in society that would be brought about by the natural decay of the business enterprise system and by the inventiveness of engineers. Daniel Bell sees an affinity between Veblen and the Technocracy movement. Janet Knoedler and Anne Mayhew demonstrate the significance of Veblen's association with these engineers, while arguing that his book was more a continuation of his previous ideas than the advocacy others see in it.

In 1927 Veblen returned to the property that he still owned in Palo Alto and died there in 1929. His death came less than three months before the momentous crash of the U.S. stock market, which heralded the Great Depression.

Veblen and other American institutionalists were indebted to the German Historical School, especially Gustav von Schmoller, for the emphasis on historical fact, their empiricism and especially a broad, evolutionary framework of study. Veblen admired Schmoller but criticized some other leaders of the German school because of their over - reliance on descriptions, long displays of numerical data and narratives of industrial development came with no underlying economic theory. Veblen tried to use the same approach with his own theory added.

Veblen developed a 20th century evolutionary economics based upon Darwinian principles and new ideas emerging from anthropology, sociology and psychology. Unlike the neoclassical economics that was emerging at the same time, Veblen described economic behavior as socially determined and saw economic organization as a process of ongoing evolution. Veblen strongly rejected any theory based on individual action or any theory highlighting any factor of an inner personal motivation. Such theories were according to him "unscientific." This evolution was driven by the human instincts of emulation, predation, workmanship, parental bent and idle curiosity. Veblen wanted economists to grasp the effects of social and cultural change on economic changes. In The Theory of the Leisure Class, the instincts of emulation and predation play a major role. People, rich and poor alike, attempt to impress others and seek to gain advantage through what Veblen coined "conspicuous consumption" and the ability to engage in “conspicuous leisure.” In this work Veblen argued that consumption is used as a way to gain and signal status. Through "conspicuous consumption" often came "conspicuous waste," which Veblen detested.

In The Theory of Business Enterprise, which was published in 1904 during the height of American concern with the growth of business combinations and trusts, Veblen employed his evolutionary analysis to explain these new forms. He saw them as a consequence of the growth of industrial processes in a context of small business firms that had evolved earlier to organize craft production. The new industrial processes impelled integration and provided lucrative opportunities for those who managed it. What resulted was, as Veblen saw it, a conflict between businessmen and engineers, with businessmen representing the older order and engineers as the innovators of new ways of doing things. In combination with the tendencies described in The Theory of the Leisure Class, this conflict resulted in waste and “predation” that served to enhance the social status of those who could benefit from predatory claims to goods and services.

Veblen generalized the conflict between businessmen and engineers by saying that human society would always involve conflict between existing norms with vested interests and new norms developed out of an innate human tendency to manipulate and learn about the physical world in which we exist. He also generalized his model to include his theory of instincts, processes of evolution as absorbed from Sumner, as enhanced by his own reading of evolutionary science, and Pragmatic philosophy first learned from Peirce. The instinct of idle curiosity led humans to manipulate nature in new ways and this led to changes in what he called the material means of life. Because, as per the Pragmatists, our ideas about the world are a human construct rather than mirrors of reality, changing ways of manipulating nature lead to changing constructs and to changing notions of truth and authority as well as patterns of behavior (institutions). Societies and economies evolve as a consequence, but do so via a process of conflict between vested interests and older forms and the new. Veblen never wrote with any confidence that the new ways were better ways, but he was sure in the last three decades of his life that the American economy could have, in the absence of vested interests, produced more for more people. In the years just after World War I he looked to engineers to make the American economy more efficient.

In addition to The Theory of the Leisure Class and The Theory of Business Enterprise, Veblen’s monograph "Imperial Germany and the Industrial Revolution", and his many essays, including “Why is Economics Not an Evolutionary Science,” and “The Place of Science in Modern Civilization,” remain influential.

In spite of difficulties of sometimes archaic language, caused in large part by Veblen’s struggles with the terminology of unilinear evolution and of biological determination of social variation that still dominated social thought when he began to write, Veblen’s work remains relevant, and not simply for the phrase “conspicuous consumption”. His evolutionary approach to the study of economic systems is once again in vogue and his model of recurring conflict between the existing order and new ways can be of great value in understanding the new global economy.

The handicap principle of evolutionary sexual selection is often compared to Veblen's “conspicuous consumption”.

Veblen, as noted, is regarded as one of the co-founders (with John R. Commons, Wesley C. Mitchell, and others) of the America school of institutional economics. Present day practitioners who adhere to this school organize themselves in the Association for Evolutionary Economics (AFEE) and the Association for Institutional Economics (AFIT). AFEE gives an annual Veblen - Commons award for work in Institutional Economics and publishes the Journal of Economic Issues. Some unaligned practitioners include theorists of the concept of "differential accumulation".

Veblen is cited in works of feminist economists.

Veblen’s work has also often been cited in treatments of American literature.

One of Veblen's Ph.D. students was George W. Stocking, Sr., a pioneer in the emerging field of industrial organization economics.