<Back to Index>

- Foreign Minister of Russia Count Alexander Petrovich Izvolsky, 1856

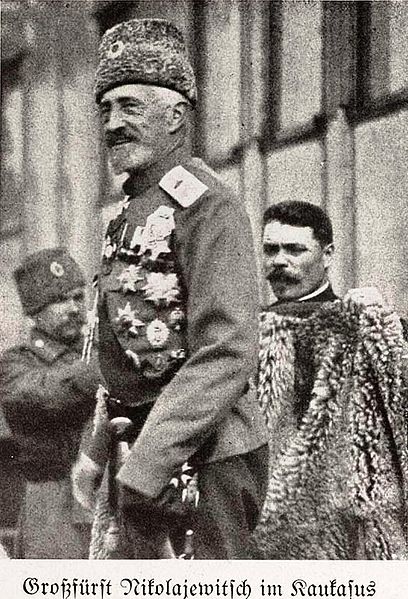

- General of the Russian Army Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich Romanov, 1856

PAGE SPONSOR

Count Alexander Petrovich Izvolsky or Iswolsky (Russian: Александр Петрович Извольский, 18 March [O.S. 6 March] 1856, Moscow – 16 August 1919, Paris) was a Russian diplomat remembered as a major architect of Russia's alliance with the British Empire during the years leading to the outbreak of the First World War.

Having graduated from the Alexander Lyceum

with honors, Izvolsky married Countess von Toll, from a family with

far reaching connections at court, and joined the Foreign Office, where

he was patronized by Prince Lobanov - Rostovsky. Following stints as

Russia's ambassador in Vatican, Belgrade, Munich, Tokyo (from 1899) and

Copenhagen (from 1903), he served as Imperial Foreign Minister between April 1906 and November 1910 and then as Russian ambassador to France.

In the wake of the disastrous Russo - Japanese War and the Russian Revolution of 1905, Izvolsky was determined to give Russia a decade of peace. He believed that it was Russia's interest to disengage from the conundrum of European politics and to concentrate on internal reforms. A constitutional monarchist, he undertook the reform and modernization of the Foreign Office.

In the realm of more practical politics, Izvolsky advocated a gradual rapprochement with Russia's traditional foes - Great Britain and Japan. He had to face vigorous opposition from several directions, notably from the public opinion and the hard liners in the military, who demanded a revanchist war against Japan and military advance into Afghanistan. His allies in the government included Pyotr Stolypin and Vladimir Kokovtsov.

Having been approached by King Edward VII during the Russo - Japanese War

with a proposal of alliance, he made it a primary aim of his policy

when he became Foreign Minister, feeling that Russia, weakened by the

war with Japan, needed another ally besides France; this resulted in the

Anglo - Russian Convention of 1907.

Another primary objective was to realize Russia's long standing goal of opening (i.e., permitting free transit, without prior conditions; and in exclusive right to Russia) the Bosporus and the Dardanelles (known jointly as the "Straits") to Russian warships, giving Russia free passage to the Mediterranean and making it possible to use the Black Sea Fleet not just in the coastal defense of her Black Sea territory; but also in support of her global interests in self defense; and in the defense of her allies. To this end Izvolsky met with the Austrian Foreign Minister, Baron (later Count) Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal, at the Moravian castle of Buchlov on September 15, 1908, and there agreed to support Austria's (proported future) annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in exchange for Austria's assent to the opening of the Straits to Russia; and to support such an opening, at any subsequent diplomatic conference.

After their meeting, Izvolsky's understanding was that these alterations of the terms of the Treaty of Berlin

would only be the terms and conditions that they each (by their prior

agreement) had privately made to support each other at a future

conference of the powers that had signed the Berlin treaty. He was

shocked and felt personally betrayed when Austria, almost immediately

after their meeting, announced its annexation of Bosnia

on October 6. Izvolsky, rebuffed by France and Britain in his attempt

to gain support for a "Conference", at which he hoped to initiate talks

about the opening of the Straits, tried unsuccessfully to have a meeting

called to deal with Austria's fait accompli. Forced by German

mediation (he was personally under threat to have his private

discussions with Von Aehrenthall revealed) to acquiesce in the

annexation and reviled by Russian pan - Slavists for "betraying" the

Serbs (who felt Bosnia should be theirs), the embittered Izvolsky was

eventually dismissed from office.

Upon becoming ambassador in Paris in 1910, Izvolsky devoted his energies to strengthening Russia's bonds with France and Britain and encouraging Russian rearmament. When World War I broke out, he is reputed to have remarked, "C'est ma guerre!" ("This is my war!").

After the February Revolution Izvolsky resigned but remained in

Paris, where he was succeeded by Vasily Maklakov. He advocated the

Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War and wrote a book of memoirs before his sudden death in August 1919. His daughter Hélène Iswolsky

subsequently was received into the Russian Catholic Church and became a

prominent scholar, first in France and later in the United States.

Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich Romanov of Russia (Russian: Николай Николаевич Романов (младший - the younger)) (November 6, 1856 – January 5, 1929) was a Russian general in World War I. A grandson of Nicholas I of Russia, he was commander in chief of the Russian armies on the main front in the first year of the war, and was later a successful commander in the Caucasus.

Nicholas, named after his paternal grandfather the emperor, was born as the eldest son to Grand Duke Nicholas Nicolaevich of Russia (1831 – 1891) and Alexandra Petrovna of Oldenburg (1838 – 1900). His father was the sixth child and third son born to Nicholas I of Russia and his Empress consort Alexandra Fedorovna of Prussia (1798 – 1860). Alexandra Fedorovna was a daughter of Frederick William III of Prussia and Louise of Mecklenburg - Strelitz.

Nicholas' mother, his father's first cousin's daughter, was a daughter of Duke Konstantin Peter of Oldenburg (1812 – 1881) and Princess Therese of Nassau (1815 – 1871). His maternal grandfather was a son of Duke George of Oldenburg and Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna of Russia, daughter of Paul I of Russia and Maria Fedorovna of Württemberg. (Catherine was later remarried to William I of Württemberg.) His maternal grandmother was a daughter of Wilhelm, Duke of Nassau (1792 – 1839) and Princess Luise of Saxe - Hildburghausen. The Duke of Nassau was a son of Friedrich Wilhelm, Duke of Nassau (1768 – 1816) and Burgravine Louise Isabelle of Kirchberg. His paternal grandparents were Duke Karl Christian of Nassau - Weilburg (1735 – 1788) and Carolina of Orange - Nassau. Carolina was a daughter of William IV of Orange and Anne, Princess Royal of Great Britain. Anne was the eldest daughter of George II of Great Britain and Caroline of Ansbach.

Grand Duke Nicholas was the first cousin once removed of the Tsar Nicholas II.

To distinguish both of them, the Grand Duke was often known within the

Imperial family as Nikolasha. The Grand Duke also towered over the Tsar,

so they were nicknamed "Nicholas the Tall" and "Nicholas the Short",

respectively.

Grand Duke Nicholas was educated at the school of military engineers and received his commission in 1872. During the Russo - Turkish War, 1877 - 78, he was on the staff of his father who was commander in chief. He distinguished himself on two occasions in this war. He worked his way up through all the ranks until he was appointed commander of the Guard Hussar Regiment in 1884.

He had a reputation as a tough commander, yet one respected by his troops. His experience was more as a trainer of soldiers than a leader in battle. Nicholas was a very religious man, praying in the morning and at night as well as before and after meals. He was happiest in the country, hunting or caring for his estates.

Nicholas was a panslavist nationalist, though not a radical one.

By 1895, he was inspector general of the cavalry, a post he held for 10 years. His tenure has been judged a success with reforms in training, cavalry schools, cavalry reserves and the remount services. He was not given an active command during the Russo - Japanese War, perhaps because the Czar did not wish to hazard the prestige of the Romanovs and because he wanted a loyal general in command at home in case of domestic disturbances. Thus, Nicholas did not have the opportunity to gain experience in battlefield command.

Grand Duke Nicholas played a crucial role during the first Russian Rebellion of 1905. With anarchy spreading and the future of the dynasty at stake, the Czar had a choice of instituting the reforms suggested by Count Sergei Witte or imposing a military dictatorship. The only man with the prestige to keep the allegiance of the army in such a coup was the Grand Duke. The Czar asked him to assume the role of a military dictator. In an emotional scene at the palace, Nicholas refused, drew his pistol and threatened to shoot himself on the spot if the Czar did not endorse Witte's plan. This act was decisive in forcing Nicholas II to agree to the reforms.

Empress Alexandra (born Alix of Hesse - Darmstadt), a convinced autocrat, never forgave the Grand Duke.

From 1905 to the outbreak of World War I, he was commander - in - chief of the St. Petersburg

Military District. He had the reputation there of appointing men of

humble origins to positions of authority. The lessons of the

Russo - Japanese War were drilled into his men.

On April 29, 1907, Nicholas married Princess Anastasia of Montenegro, the daughter of King Nicholas of Montenegro. She had previously been married to George Maximilianovich, 6th Duke of Leuchtenberg until their divorce in 1906. Their marriage was a happy one. Both were deeply religious Orthodox Christians, with a tendency to mysticism. Since the Montenegrins were a fiercely Slavic, anti - Turkish people from the Balkans, Anastasia reinforced the Pan - Slavic tendencies of Nicholas. They had no children.

He had maybe five illegitimate children with Thérèse Lobiewski:

- Xenia (b. 17th September 1918)

- Bartholomew (b. 5th December 1919)

- David (d. 1966)

- Nicholas (b. 3rd March 1923)

- Anastasia (b. 1924)

The Grand Duke had no part in the planning and preparations for World War I, that being the responsibility of General Vladimir Sukhomlinov and the general staff. On the eve of the outbreak of World War I, his first cousin once removed, the Emperor Nicholas II of Russia, yielded to the entreaties of his ministers and appointed Grand Duke Nicholas to the supreme command. He was 57 years old and had never commanded armies in the field before. He was given responsibility for the largest army ever put into the field in all prior history.

Grand Duke Nicholas was responsible for all Russian forces fighting against Germany, Austria - Hungary, and Turkey. Initially, the Russian high command was not up to the challenge of the Great War. Different armies failed to coordinate their actions which resulted in the disaster of Tannenberg. The subsequent Battle of the Vistula River and Battle of Łódź were more successful for the Russian army. The Grand Duke's role was limited to picking and choosing from the various plans offered by the many Russian Army Generals. No coherent plan for victory emerged from the Grand Duke or his staff, though on a personal level he was well liked by both officers and the troops.

Nicholas seems to have been more a bureaucrat than a military leader, lacking the broad strategic sense and the ruthless drive to command all the Russian armies. His headquarters had a curiously calm atmosphere, despite the many defeats and the millions of casualties. It must be admitted that the Russian army did not perform any better with his cousin, the Tsar, in charge of the war. On March 22, 1915 he reсeived the Order of St. George 2nd degree for the successful Siege of Przemyśl.

After the strategic retreat of the Russian army (and at the suggestion of Grigori Rasputin,

the Imperial Family's spiritual advisor), the Tsar replaced the Grand

Duke as commander of the Russian armed forces on August 21, 1915.

Upon his dismissal, the Grand Duke was immediately appointed commander - in - chief and viceroy in the Caucasus area (taking over for the old Governor General Illarion Vorontsov). While the Grand Duke was officially in command, General Yudenich was the driving figure in the Russian Caucusus army. Their opponent was the Ottoman Empire. While the Grand Duke was in command, the Russian army sent an expeditionary force through to Persia (now Iran) to link up with British troops. Also in 1916, the Russian army captured the Fortress of Erzerum, the port of Trebizond (now Trabzon) and the town of Erzincan. The Turks responded with an offensive of their own. Fighting around Lake Van swung back and forth, but ultimately proved inconclusive.

Nicholas tried to have a railway built from Russian Georgia to the

conquered territories with a view to bringing up more supplies for a new

offensive in 1917. But, in March 1917, the Tsar was overthrown and the

Russian army began to slowly fall apart.

The February Revolution found Nicholas in the Caucasus. He was appointed by the Emperor, in his last official act, as the supreme commander in chief, and was wildly received as he journeyed to headquarters in Mogilev; however, within 24 hours of his arrival, the new premier, Prince Georgy Lvov, canceled his appointment. Nicholas spent the next two years in the Crimea, sometimes under house arrest, taking little part in politics. There appears to have been some sentiment to have him head the White Russian forces active in southern Russia at the time, but the leaders in charge, especially General Anton Denikin, were afraid that a strong monarchist figurehead would alienate the more left leaning constituents of the movement. He and his wife escaped just ahead of the Red Army in April 1919, aboard the British Battleship HMS Marlborough.

On August 8, 1922, Nicholas was proclaimed as the emperor of all Russia by the Zemsky Sobor of the Preamursk region by general Mikhail Diterikhs.

The former was already living abroad and consequently was not present.

Two months later the Preamursk region fell to the Bolsheviks.

After a stay in Genoa as a guest of his brother - in - law, Victor Emmanuel III, King of Italy, Nicholas and his wife took up residence in a small castle at Choigny, 20 miles outside of Paris. He was under the protection of the French secret police as well as by a small number of faithful Cossack retainers. He became the center of an anti - Soviet monarchist resistance group, and headed the Russian All Military Union alongside general Pyotr Wrangel. Plans were made by them to send their agents into Russia. Conversely a top priority of the Soviet secret police was to penetrate this monarchist organization and to kidnap Nicholas. They were successful in the former, infiltrating the group with spies, and later luring the anti - Bolshevik British master spy Sidney Reilly back to the Soviet Union where he was killed. They did not succeed however, with kidnapping Nicholas. As late as June 1927, the monarchists were able to set off a bomb at the Lubyanka Prison in Moscow.

Grand Duke Nicholas died on January 5, 1929 of natural causes on the French Riviera, where he had gone to escape the rigors of winter.