<Back to Index>

- Philosopher

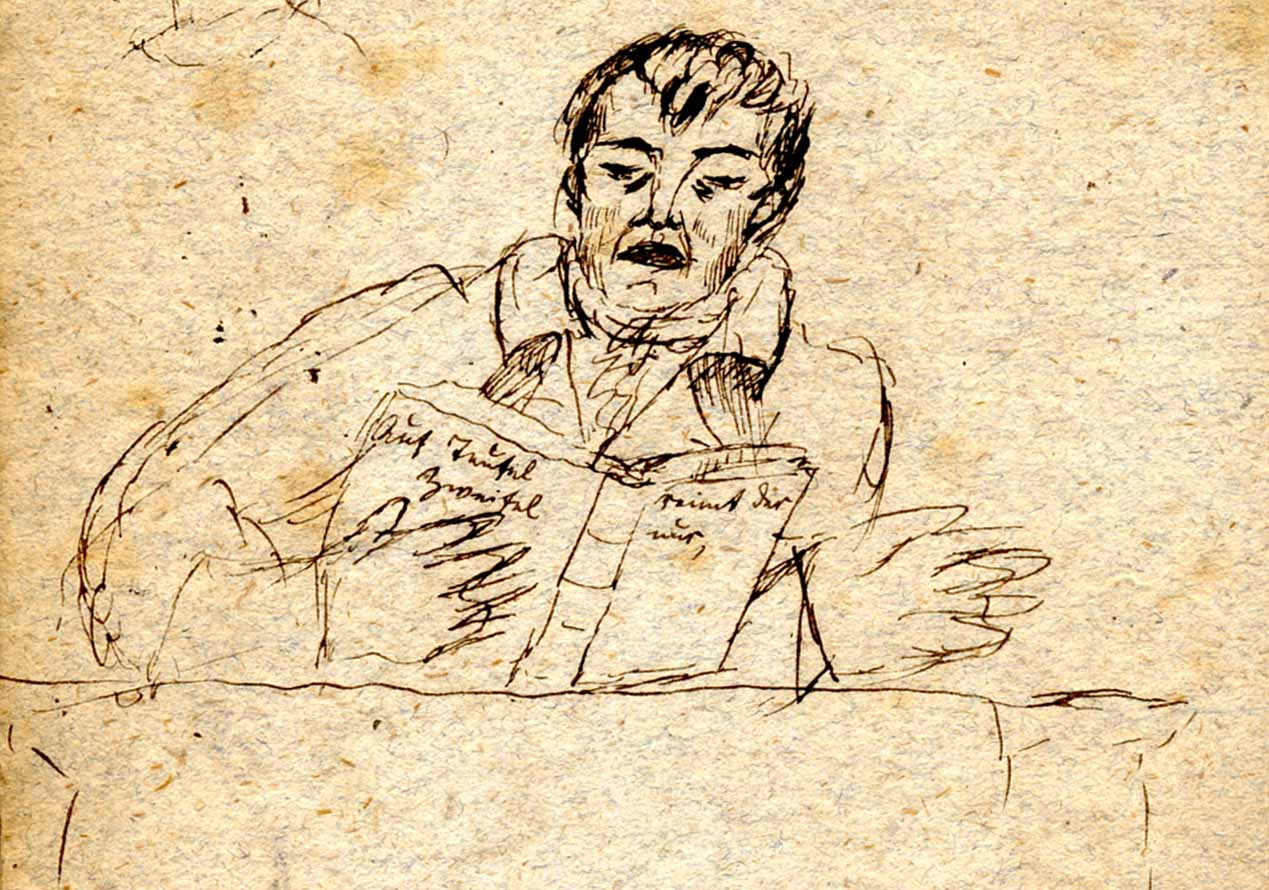

Gottlob Ernst Schulze,

1761

PAGE SPONSOR

Gottlob Ernst Schulze (23 August 1761 - 14 January 1833) was born in Heldrungen (modern day Thuringia, Germany). Schulze was a professor at Wittenberg, Helmstedt and Göttingen. His most influential book was Aenesidemus, a skeptical polemic against Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason and Karl Leonhard Reinhold's Philosophy of the Elements.

In Göttingen, he advised his student Arthur Schopenhauer to concentrate on the philosophies of Plato and Kant. This advice had a strong influence on Schopenhauer's philosophy. In the winter semester of 1810 and 1811, Schopenhauer studied both psychology and metaphysics under Schulze.

He died in Göttingen.

- "By wild imaginings, however, are also understood all those states in which we take mere fictions and figures of the imagination to be objectively valid knowledge."

- "Mental disorders occur merely through luxury and are not to be found among savages."

- "A particular kind of simile is called wit … Its products consist of ideas about hidden yet superficial similarities of things."

- "Truth is a curved line and philosophy is the number of tangents which approach it to infinity without ever reaching it, - the asymptotes."

- "The settlement whether a judgment is analytic or synthetic depends, moreover, on how far we extend the concept of the subject, so that what to one is analytic is to another synthetic."

- "Who knows nature - in - itself?"

- "It is said that, since the skeptic, when he takes part in the affairs of life assumes as indubitable the reality of objective things, behaves accordingly, and thus admits a criterion of truth, his own behavior is the best and clearest refutation of his skepticism. Such proofs are only valid for the common mob. My skepticism does not concern the requirements of practical life, but remains within the bounds of philosophy."

- "As determined by the Critique of Pure Reason, the function of the principle of causality thus undercuts all philosophizing about the where or how of the origin of our cognitions. All assertions on the matter, and every conclusion drawn from them, become empty subtleties, for once we accept that determination of the principle as our rule of thought, we could never ask, "Does anything actually exist which is the ground and cause of our representations?". We can only ask, "How must the understanding join these representations together, in keeping with the pre-determined functions of its activity, in order to gather them as one experience?"