<Back to Index>

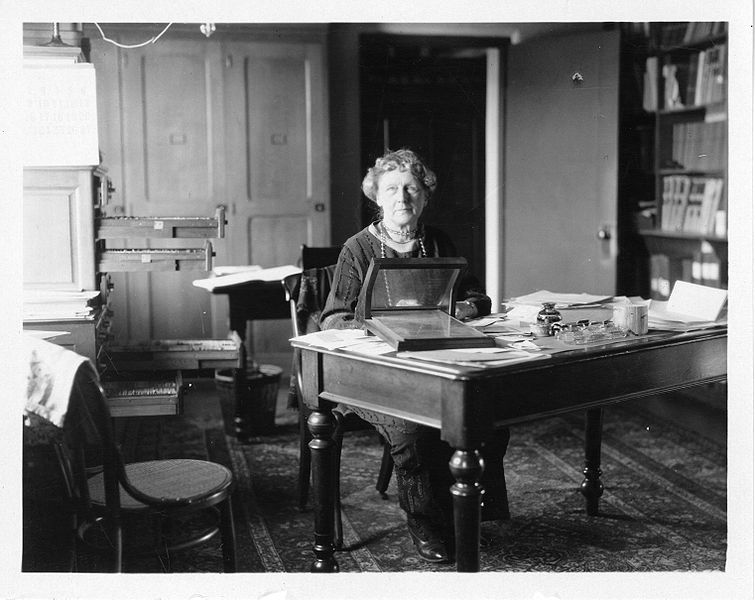

- Astronomer Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming, 1857

- Astronomer Annie Jump Cannon, 1863

PAGE SPONSOR

Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming (May 15, 1857 – May 21, 1911) was a Scottish American astronomer. During her career, she helped develop a common designation system for stars and cataloged thousands of stars and other astronomical phenomena. Fleming is especially noted for her discovery of the Horsehead nebula in 1888.

Fleming was born in Dundee, Scotland, to Robert Stevens and Mary Walker Stevens. She attended public schools in Dundee. At the age of 14, she became a pupil - teacher. She married James Orr Fleming, and they moved to the U.S. and settled in Boston, Massachusetts, when she was 21. While she was pregnant with her son, Edward, her husband abandoned her, and she had to find work to support herself and Edward.

She worked as a maid in the home of Professor Edward Charles Pickering. Pickering became frustrated with his male assistants at the Harvard College Observatory and, legend has it, famously declared his maid could do a better job.

In 1881, Pickering hired Fleming to do clerical work at the observatory. While there, she devised and helped implement a system of assigning stars a letter according to how much hydrogen could be observed in their spectra. Stars classified as A had the most hydrogen, B the next most, and so on. Later, Annie Jump Cannon would improve upon this work to develop a simpler classification system based on temperature.

Fleming contributed to the cataloging of stars that would be published as the Henry Draper Catalog. In nine years, she cataloged more than 10,000 stars. During her work, she discovered 59 gaseous nebulae, over 310 variable stars, and 10 novae. In 1907, she published a list of 222 variable stars she had discovered.

In 1888, Mrs. Fleming discovered the Horsehead nebula on Harvard plate B2312, describing the bright nebula (later known as IC-434) as having "a semicircular indentation 5 minutes in diameter 30 minutes south of Zeta [Orionis]." The brother of Edward Pickering, William Henry Pickering, who had taken the photograph, speculated that the spot was dark obscuring matter. All subsequent articles and books seem to deny Fleming and W.H. Pickering credit, because the compiler of the first Index Catalog, J.L.E. Dreyer, eliminated Mrs. Fleming's name from the list of objects then discovered by Harvard, attributing them all instead merely to "Pickering" (taken by most readers to mean E.C. Pickering, Director of Harvard College Observatory.) But, by the release of the second Index Catalog by Dreyer in 1908, Mrs. Fleming and others at Harvard were famous enough to receive proper credit for later object discoveries -- but not for IC-434 and the Horsehead, one of her early observations.

Fleming was placed in charge of dozens of women hired to do mathematical classifications and edited the observatory's publications. In 1899, Fleming was given the title of Curator of Astronomical Photographs. In 1906, she was made an honorary member of the Royal Astronomical Society of London, the first American woman to be so elected. Soon after, she was appointed honorary fellow in astronomy of Wellesley College. Shortly before her death, the Astronomical Society of Mexico awarded her the Guadalupe Almendaro medal for her discovery of new stars. She published A Photographic Study of Variable Stars (1907) and Spectra and Photographic Magnitudes of Stars in Standard Regions (1911).

She died in Boston of pneumonia.

Annie Jump Cannon (December 11, 1863 – April 13, 1941) was an American astronomer whose cataloging work was instrumental in the development of contemporary stellar classification. With Edward C. Pickering, she is credited with the creation of the Harvard Classification Scheme, which was the first serious attempt to organize and classify stars based on their temperatures.

The daughter of shipbuilder and state senator Wilson Lee Cannon and his second wife, Mary Elizabeth Jump, Cannon grew up in Dover, Delaware. Cannon's mother had a childhood interest in star gazing, and she passed that interest along to her daughter. She had four older step - siblings from her father's first marriage, as well as two brothers, Robert and Wilson. Cannon never married but was happy to be an aunt to her brother's children.

At Wilmington Conference Academy, Cannon was a promising student, particularly in mathematics. In 1880 Cannon was sent to Wellesley College in Massachusetts, one of the top academic schools for women in the U.S. The cold winter climate in the area led to repeated infections, and in one Cannon was stricken with scarlet fever. As a result, Cannon became almost completely deaf.

She graduated with a degree in physics in 1884 and returned home. Uninterested in the limited career opportunities available to women, she grew bored and restless. Her partial hearing loss made socializing difficult, and she was generally older and better educated than most of the unmarried women in the area. She had made a trip to Europe in 1892 to photograph the solar eclipse, but returned with her situation little improved.

In 1894, however, her mother died. Life in the home grew more difficult, and she finally wrote to her former instructor at Wellesley, Professor of Physics and Astronomy Sarah Frances Whiting, to see if there was a job opening. Whiting hired her as her assistant, which allowed Cannon to take graduate courses at the college. The school had started offering a course in astronomy, which became her true calling. While at Wellesley, Professor Whiting inspired her to learn about spectroscopy. Also during those years, Cannon developed her skills in the new art of photography.

She returned to Wellesley in 1894 for graduate study in physics and astronomy. In order to gain access to a better telescope, she decided to enroll at Radcliffe Women's College at Harvard, which had access to the Harvard College Observatory. In 1896, Edward C. Pickering hired Cannon as his assistant at the Harvard observatory. By 1907 she had received a MA from Wellesley.

In 1896 Cannon became a member of Pickering’s women, the women hired by Harvard Observatory director Edward Charles Pickering to complete the Draper Catalog mapping and defining all the stars in the sky to photographic magnitude of about 9.

Anna Draper, the widow of Henry Draper, who was a wealthy physician and amateur astronomer, set up a fund to support the work. Pickering made the Henry Draper Catalog a long term project to obtain the optical spectra of as many stars as possible, and also to index and classify stars by spectra. If making measurements was hard enough, the development of a reasonable classification was at least as difficult.

Not long after the work on the Draper Catalog began, a disagreement developed as to how to classify the stars. Antonia Maury, who was also Henry Draper's niece, insisted on a complex classification system while Williamina Fleming, who was overseeing the project for Pickering, wanted a much simpler, straightforward approach. Cannon negotiated a compromise. She started by examining the bright southern hemisphere stars. To these stars she applied a third system, a division of stars into the spectral classes O, B, A, F, G, K, M. Her scheme was based on the strength of the Balmer absorption lines. After absorption lines were understood in terms of stellar temperatures her initial classification system was rearranged to avoid having to update star catalogs. The mnemonic of "Oh Be A Fine Girl, Kiss Me" has developed as a way to remember stellar classification.

The female astronomers doing this groundbreaking work at Harvard Observatory earned 25 cents per hour, which was less than what the secretaries at the university earned.

Cannon’s work was “theory - laced” but simplified. Her observation of stars and stellar spectra was extraordinary. Her Henry Draper Catalog listed nearly 230,000 stars, all the work of a single observer. Cannon also published other catalogs of variable stars, including 300 that she discovered. Her career lasted more than 40 years, during which time women gained acceptance within the scientific community.

Annie Jump Cannon died April 13, 1941 after receiving a regular Harvard appointment as the William C. Bond Astronomer. She also received the Henry Draper Medal, which only one other female has won, Martha P. Haynes (who shared it with a male colleague).