<Back to Index>

- Socialist and Political Activist Louis Auguste Blanqui, 1805

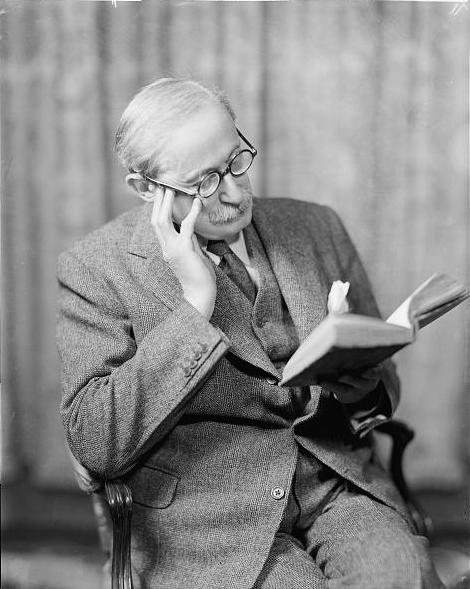

- Prime Minister of France André Léon Blum, 1872

PAGE SPONSOR

Louis Auguste Blanqui (8 February 1805, Puget - Théniers, Alpes - Maritimes – 1 January 1881, Paris) was a French socialist and political activist, notable for his revolutionary theory of Blanquism.

Blanqui was born in Puget - Théniers, Alpes - Maritimes, where his father, Jean Dominique Blanqui, was subprefect. He was the younger brother of the liberal economist Jérôme - Adolphe Blanqui. He studied both law and medicine, but found his real vocation in politics, and quickly became a champion of the most advanced opinions. A member of the Carbonari society since 1824, he took an active part in most republican conspiracies during this period. In 1827, under the reign of Charles X (1824 – 1830), he participated in a street fight in Rue Saint - Denis, during which he was seriously injured. In 1829, he joined Pierre Leroux's Globe newspaper before taking part in the July Revolution of 1830. He then joined the Amis du Peuple ("Friends of the People") society, where he made acquaintances with Philippe Buonarroti, Raspail and Armand Barbès. He was condemned to repeated terms of imprisonment for maintaining the doctrine of republicanism during the reign of Louis Philippe (1830 – 1848). In May 1839, a Blanquist inspired uprising took place in Paris, in which the League of the Just, forerunners of Karl Marx's Communist League, participated.

Implicated in the armed outbreak of the Société des Saisons, of which he was a leading member, Blanqui was condemned to death on 14 January 1840, a sentence later commuted to life imprisonment.

He was released during the revolution of 1848, only to resume his attacks on existing institutions. The revolution had not satisfied him. The violence of the Société républicaine centrale, which was founded by Blanqui to demand a change of government, brought him into conflict with the more moderate Republicans, and in 1849 he was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment. While in prison, he sent a brief address (written in the Prison of Belle - Ile - en - Mer, 10 February 1851) to a committee of social democrats in London. The text of the address was noted and introduced by Marx.

In 1865, while serving a further term of imprisonment under the Empire, he escaped, and continued his propaganda campaign against the government from abroad, until the general amnesty of 1869 enabled him to return to France. Blanqui's predilection for violence was illustrated in 1870 by two unsuccessful armed demonstrations: one on 12 January at the funeral of Victor Noir, the journalist shot by Pierre Bonaparte; the other on 14 August, when he led an attempt to seize some guns from a barracks. Upon the fall of the Empire, through the revolution of 4 September, Blanqui established the club and journal La patrie en danger.

He was one of the group that briefly seized the reins of power on 31 October and for his share in that outbreak he was again condemned to death in absentia on 9 March of the following year. On 17 March, Adolphe Thiers, aware of the threat represented by Blanqui, took advantage of his resting at a friend physician's place, in Bretenoux in Lot, and had him arrested. A few days afterwards the insurrection which established the Paris Commune broke out, and Blanqui was elected president of the insurgent commune. The Communards offered to release all of their prisoners if the Thiers government released Blanqui, but their offer was met with refusal, and Blanqui was thus prevented from taking an active part. Karl Marx would later be convinced that Blanqui was the leader that was missed by the Commune. Nevertheless, in 1872 he was condemned along with the other members of the Commune to transportation; on account of his broken health this sentence was again commuted to one of imprisonment. On 20 April 1879 he was elected a deputy for Bordeaux; although the election was pronounced invalid, Blanqui was freed, and immediately resumed his work of agitation.

As a socialist, Blanqui favored a just redistribution of wealth. But Blanquism is distinguished in various ways from other socialist currents of the day. On one side, contrary to Karl Marx, Blanqui did not believe in the preponderant role of the working class, nor in popular movements: he thought, on the contrary, that the revolution should be carried out by a small group, who would establish a temporary dictatorship by force. This period of transitional tyranny would permit the implementation of the basis of a new order, after which power would be handed to the people. In another respect, Blanqui was more concerned with the revolution itself than with the future society that would result from it: if his thought was based on precise socialist principles, it rarely goes so far as to imagine a society purely and really socialist. In this he differs from the Utopian Socialists. For the Blanquists, the overturning of the bourgeois social order and the revolution are ends sufficient in themselves, at least for their immediate purposes. He was one of the non - Marxist socialists of his day.

Following a speech at a political meeting in Paris, Blanqui had a stroke. He died on 1 January 1881 and was interred in the Père Lachaise Cemetery. His elaborate tomb was created by Jules Dalou.

Blanqui's uncompromising radicalism, and his determination to enforce it by violence, brought him into conflict with every French government during his lifetime, and as a consequence, he spent half of his life in prison. Besides his innumerable contributions to journalism, he published a work entitled, L'Eternité par les astres (1872), where he espoused his views concerning eternal return. After his death his writings on economic and social questions were collected under the title of Critique sociale (1885).

The Italian fascist newspaper Il Popolo d'Italia, founded and edited by Benito Mussolini, had a quotation by Blanqui on its mast: "Chi ha del ferro ha del pane" ("He who has iron, has bread").

André Léon Blum (9 April 1872 – 30 March 1950) was a French politician, usually identified with the moderate left, and three times Prime Minister of France.

While in his youth an avid reader of the works of the nationalist writer Maurice Barrès, Blum had little interest in politics until the Dreyfus Affair of 1894, which had a traumatic effect on him as it did on many French Jews. Campaigning as a Dreyfusard brought him into contact with the socialist leader Jean Jaurès, whom he greatly admired. He began contributing to the socialist daily, L'Humanité, and joined the Socialist Party, then called the SFIO. Soon he was the party's main theoretician.

In July 1914, just as the First World War broke out, Jaurès was assassinated, and Blum became more active in the Socialist party leadership. In August 1914 Blum became assistant to the Socialist Minister of Public Works Marcel Sembat. In 1919 he was chosen as chair of the party's executive committee, and was also elected to the National Assembly as a representative of Paris. Believing that there was no such thing as a "good dictatorship", he opposed participation in the Comintern. Therefore, in 1920, he worked to prevent a split between supporters and opponents of the Russian Revolution, but the radicals seceded, taking L'Humanité with them, and formed the SFIC.

Blum led the SFIO through the 1920s and 1930s, and was also editor of the party's new paper, Le Populaire.

Blum was elected as Deputy for Narbonne in 1929, and was re-elected in 1932 and 1936. In 1933, he expelled Marcel Déat, Pierre Renaudel, and other neo - socialists from the SFIO. Political circumstances changed in 1934, when the rise of German dictator Adolf Hitler and fascist riots in Paris caused Stalin and the French Communists to change their policy. In 1935 all the parties of left and center formed the Popular Front, which at the elections of June 1936 won a sweeping victory.

On 13 February 1936, shortly before becoming Prime Minister, Blum was dragged from a car and almost beaten to death by the Camelots du Roi, a group of anti - Semites and royalists. The right wing Action Française league was dissolved by the government following this incident, not long before the elections that brought Blum to power.

Blum became the first socialist and the first Jew to serve as Prime Minister of France. As such he was an object of particular hatred to the Catholic and anti - Semitic right, and was denounced in the National Assembly by Xavier Vallat, a right wing Deputy and sympathizer of the Action Française (later Commissioner for Jewish Affairs in the Vichy wartime government), who said:

Your coming to power is undoubtedly a historic event. For the first time this old Gallo - Roman country will be governed by a Jew. I dare say out loud what the country is thinking, deep inside : it is preferable for this country to be led by a man whose origins belong to his soil... than by a cunning talmudist.

The industrial workers responded to the election of the Popular Front government by occupying their factories, confident that "the revolution" was imminent. For Blum, as a Marxist, this was an agonizing moment. He did not believe that socialism could be achieved by parliamentary means. But he could not encourage the workers to launch a violent revolution : he believed that the army would intervene and the poor workers would be massacred again as they had been at the Paris Commune in 1871. He persuaded the workers to accept pay raises and go back to work.

Similarly, when the Spanish Civil War broke out, Blum was forced to adopt a policy of neutrality rather than assist his ideological fellows, the Spanish Left - leaning Republicans, for fear of splitting his alliance with the centrist Radicals, or even precipitating a religious civil war in France. His refusal to send arms to Spain strained his alliance with Communists, who followed Soviet policy, and urged all-out support for the Spanish Republic. The impossible dilemma caused by this issue led Blum to resign in June 1937.

He was briefly Prime Minister again in March and April 1938, long enough to ship France's heavy artillery and much needed military equipment to the Spanish Republicans. Blum was unable to establish a stable ministry in France. On 10 April 1938, Blum's socialist government fell and he was removed from office.

Despite its short life, the Popular Front government passed much important legislation, including the 40 hour week, paid holidays for the workers, collective bargaining on wage claims and the nationalization of the arms industry. Blum also passed legislation extending the rights of the Arab population of Algeria. In foreign policy, his government was divided between the traditional anti - militarism of the French left and the urgency of the rising threat of Nazi Germany. Despite the division, the government managed to engage the greatest war effort since the First World War.

When the Germans occupied France in June 1940, Blum made no effort to leave the country, despite the extreme danger he was in as a Jew and a socialist leader; instead of fleeing the country, he escaped to southern France, but the French ordered his arrest. Blum was imprisoned in Fort du Portalet in the Pyrenees. With two other political leaders, he was tried in the Riom Trial for "betraying his country". He was transferred to German custody and imprisoned in Nazi Germany until 1945.

Blum was among the "The Vichy 80", a minority of parliamentarians that refused to grant full powers to Marshal Philippe Pétain. He was arrested by the authorities in September and held until 1942, when he was put on trial in the Riom Trial on charges of treason, for having "weakened France's defenses" by ordering her arsenal shipped to Spain, leaving France's infantry unsupported by heavy artillery on the eastern front against Nazi Germany. He used the courtroom to make a brilliant indictment of the French military and pro - German politicians like Pierre Laval. The trial was such an embarrassment to the Vichy regime that the Germans ordered it called off.

In April 1943, the occupying Government had Blum imprisoned in Buchenwald in the section reserved for high ranking prisoners. His future wife, Janot Blum, chose to come to the camp voluntarily to live with him inside the camp.

As the Allied armies approached Buchenwald, he was transferred to Dachau, near Munich, and in late April 1945, together with other notable inmates, to Tyrol. In the last weeks of the war the Nazi regime gave orders that he was to be executed, but the local authorities decided not to obey them. Blum was rescued by Allied troops in May 1945. While in prison he wrote his best known work, the essay À l'échelle Humaine ("For all mankind").

His brother René, the founder of the Ballet de l'Opéra à Monte Carlo, was arrested in Paris in 1942. He was deported to Auschwitz where, according to the Vrba - Wetzler report, he was tortured and killed in April 1943.

After the war, Léon Blum returned to politics, and was again briefly Prime Minister in the transitional postwar coalition government. He advocated the alliance between the center - left and the center - right parties in order to support the Fourth Republic against the Gaullists and the Communists. He also served as an ambassador on a government loan mission to the United States, and as head of the French mission to UNESCO. He continued to write for Le Populaire until his death at Jouy - en - Josas, near Paris, on 30 March 1950. The kibbutz of Kfar Blum in northern Israel is named after him.