<Back to Index>

- Prime Minister of Greece Ioannis Rallis (Ιωάννης Ράλλης), 1878

- Prime Minister of Greece Konstantinos Tsaldaris (Κωνσταντίνος Τσαλδάρης), 1884

- Prime Minister of Greece Georgios Papandreou (Γεώργιος Παπανδρέου), 1888

PAGE SPONSOR

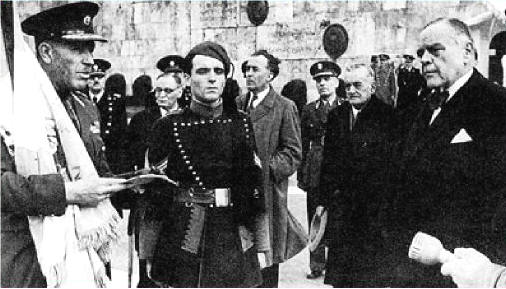

Ioannis Rallis (Ιωάννης Δ. Ράλλης; 1878, Athens – 26 October 1946, Averof Prison, Ampelokipoi, Athens) was the third and last collaborationist prime minister of Greece during the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II, holding office from 7 April 1943 to 12 October 1944, succeeding Konstantinos Logothetopoulos in the Nazi controlled Greek puppet government in Athens.

Rallis was son of the former Greek Prime Minister, Dimitrios Rallis and he came of a family with a long tradition in political leadership.

He studied law at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, as well as in France and Germany. Upon his return to Greece he became a lawyer.

In 1905, he was elected as a member of parliament for the first time;

he remained in parliament until 1936, when democracy was abolished in

Greece by the 4th of August Regime of Ioannis Metaxas.

Rallis originally belonged to the Greek conservative, monarchist People's Party. As a member of this party he served in various administrations as:

- Minister of Navy (4 November 1920 to 24 January 1921). Under Prime Minister Dimitrios Rallis, his father.

- Minister of Economics (August 26, 1921 to March 2, 1922). Under Prime Minister Dimitrios Gounaris.

- Minister of Foreign Affairs (November 4, 1932 to January 16, 1933). Under Prime Minister Panagis Tsaldaris.

After the victory of the People's Party in Greek legislative election, 1933, he served the new government under Tsaldaris from various posts. In 1935, he had a disagreement with the Prime Minister Panagis Tsaldaris, the leader of the People's Party, and at the ensuing Greek legislative election, 1935 he campaigned with Ioannis Metaxas and Georgios Stratos as a candidate of the Freethinker's Party, but he failed to win election.

Greece was in a time of great political instability and new elections were held, the Greek legislative election, 1936. This time Rallis joined with Georgios Kondylis and Ioannis Theotokis and he was elected. Parliament was fractured, with the Liberal Party under Themistoklis Sophoulis having a one seat majority and the opposition divided between monarchists and Communists and every philosophy in between.

When the Metaxas dictatorship

was declared later that year, and parliament was dissolved on August 4,

1936, Rallis expressed disapproval of this political coup, despite his

personal friendship with Metaxas.

Rallis was the first eminent Greek political figure to collaborate politically with the German occupying forces. The Germans hoped that Rallis would gain some support from the pre-war Greek political elites, that he might be able to restore order to the country and that he could form an anticommunist front against the Ethniko Apeleftherotiko Metopo (EAM, National Liberation Front) and the Ethnikos Laikos Apeleftherotikos Stratos (ELAS, National People's Liberation Army).

EAM was the main movement of the Greek Resistance and had been initially formed by an alliance of Communist Party of Greece, the Socialist Party of Greece, the Greek Popular Republic and the Agricultural Party of Greece. ELAS was its military arm. Since anti - communism served as a common ground between the Liberal Party and the People's Party, the idea of a united front seemed plausible.

Rallis changed the ministry council and was instrumental in creating the so-called "Security Battalions" (Τάγματα Ασφαλείας) - collaborationist paramilitary groups equipped by the Wehrmacht and dedicated to the persecution of resistance groups (mainly ELAS). Being more experienced in politics than his predecessors, he was more respected by the Germans and proved more effective against the resistance movements.

All three administrators during the occupation (Georgios

Tsolakoglou, Konstantinos Logothetopoulos and Ioannis Rallis) presided

over what was in effect a puppet government

(1941 - 44) completely subordinate to the Nazi occupation authorities.

Thus, they all failed to prevent the Nazis from imposing heavy

"reconstruction" fees on Greece, paid eventually by the confiscation of

crops and precipitating a terrible famine that according to the Red Cross,

cost the life of about 250,000 people (mainly in the urban areas of the

country). They also did not react to the annexation of the northern

territories of Thrace and Eastern Macedonia by the Axis partner Bulgaria.

After the liberation of Greece, Rallis was sentenced to life imprisonment for collaboration. He died in jail, in 1946.

Ioannis Rallis's son George Rallis became prime minister during 1980 – 1981. In 1947, George published a book titled Ioannis Rallis speaks from the grave, which consisted of a remorseful text written by his father during his imprisonment.

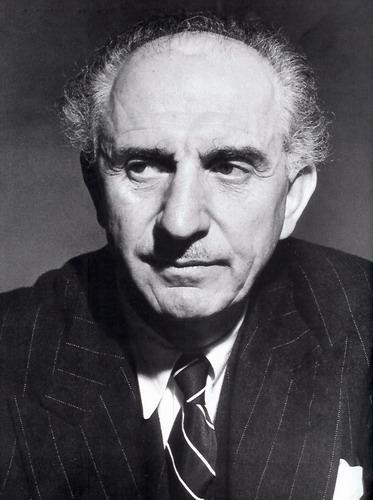

Konstantinos Tsaldaris (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Τσαλδάρης, 1884 – 1970) was a Greek politician and twice Prime Minister of Greece.

Tsaldaris was born in Alexandria, Egypt. He studied law at the University of Athens as well as Berlin, London and Florence. He became a prefectural politician from 1915 to 1917.

In 1926, he was elected as a deputy for the first time in the Argolidocorinthia prefecture (now split into Argolis and Corinthia) with the Freethinkers' Party of Ioannis Metaxas. In 1928, he became a member of the People's Party, the leader of which was his uncle Panagis Tsaldaris. He entered Panagis Tsaldaris' second government as Vice Minister of Transportation from 1933 to 1935, and continued as Under - Secretary to the Prime Minister. After the death of Panagis Tsaldaris in 1936, he became a member of the administrative commission of the People's Party, which was however soon dissolved under the dictatorship of Metaxas.

After Liberation in 1944, he was recognized as the leader of the reborn People's Party, and won in the controversial 1946 elections as leader of the right wing "United Patriotic Party" coalition and became prime minister of Greece from April 1946 through January 1947. His government carried out the plebiscite on the return of the monarchy in August 1946.

During 1947 - 1949 he acted as the head of the Greek representation in the UN General Assembly. He was Deputy Prime Minister during the governments of Dimitrios Maximos (1947), Themistoklis Sophoulis (1947 – 1949) and Alexandros Diomidis (1949 – 1950). He once again became prime minister from August 1947 until September of the same year.

With the foundation and rise to power of the Greek Rally of Marshal Alexandros Papagos,

the People's party lost a large part of its electoral base and

Tsaldaris did not win in the 1952 election. He was voted into Parliament

with the Democratic Union, in the 1956 elections, but in the 1958 elections,

as head of the Union of the People's Party, he failed to be elected.

Shortly afterwards he ended his political career. He died in Athens in

1970.

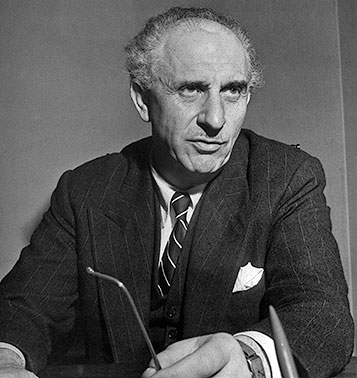

Georgios Papandreou (Greek: Γεώργιος Παπανδρέου – Geórgios Papandréou; Kalentzi, 13 February 1888 – Athens, 1 November 1968) was a Greek politician, the founder of the Papandreou political dynasty. He served three terms as Prime Minister of Greece (1944 – 1945, 1963, 1964 – 1965). He was also Deputy Prime Minister from 1950 – 1952, in the governments of Nikolaos Plastiras and Sofoklis Venizelos and served numerous times as a Cabinet Minister, starting in 1923, in a political career that spanned more than five decades.

He was born at Kalentzi, in Achaea in West Greece. He was the son of Father Andreas, an Orthodox archpriest (presvyteros). He studied Law in Athens and Political Science in Berlin. His political philosophy was heavily influenced by German social democracy. As a result, he was adamantly opposed to the monarchy and supported generous social policies, but he was also extremely anti - communist. As a young man, he became involved in politics as a supporter of the Liberal leader Eleftherios Venizelos, who made him Governor of Chios after the Balkan War of 1912. He married twice. His first wife was Sofia Mineyko, a Polish national, and their son Andreas Papandreou was born in Chios in 1919. The second wife was the actress Cybele Andrianou. They had a son Georgios G. Papandreou.

During the political crisis surrounding Greece's entry into World War I, Papandreou was one of Venizelos's closest supporters against the pro - German King Constantine I. When Venizelos was forced to flee Athens, Papandreou accompanied him to Crete, and then went to Lesbos, where he mobilized anti - monarchist supporters in the islands and rallied support for Venizelos's insurgent pro - British government in Thessaloniki. In 1921 he narrowly escaped assassination from royalist extremists.

Papandreou served as a Venizelist Member of Parliament beginning in 1920, as Interior Minister in 1923, Finance Minister in 1924 - 1925, Education Minister in 1929 - 1932, and Transport Minister in 1933. As Minister of Education he reformed the Greek school system and built many schools for the children of refugees of the Asia Minor Catastrophe. In 1935, he set up the Democratic Socialist Party of Greece. A lifelong opponent of the Greek monarchy, he was exiled in 1936 by the Greek royalist dictator Ioannis Metaxas. Following the German occupation of Greece in World War II, he joined the predominantly Venizelist government - in - exile based in Egypt (with British support, and king George II as official head of state), and in 1944 - 1945 he served as Prime Minister. Although he lost the premiership in 1945, he continued to hold high office. From 1946 - 1952 he served as Labor Minister, Supplies Minister, Education Minister, Finance Minister and Public Order Minister. In 1950 - 1952, he was also Deputy Prime Minister.

The 1952 - 1961 period was a very difficult one for Papandreou. The liberal political forces in Greece were gravely weakened by internal disputes and suffered electoral defeat from the conservatives. Papandreou continuously accused Sofoklis Venizelos for these maladies, considering his leadership dour and uninspiring. In 1961, Papandreou revived Greek liberalism by founding the Center Union Party, a confederation of old liberal Venizelists and dissatisfied conservatives. After the elections of "violence and fraud" of 1961, Papandreou declared a "Relentless Struggle" (Ανένδοτος Αγώνας) against the right wing ERE. His party won the elections of November 1963 and those of 1964, the second with a landslide majority. His progressive policies as premier aroused much opposition in conservative circles, as did the prominent role played by his son Andreas Papandreou, whose policies were seen as being considerably left of center. Andreas disagreed with his father on many important issues, and developed a network of political organizations, the Democratic Leagues (Δημοκρατικοί Σύνδεσμοι) to lobby for more progressive policies. He also managed to take control of the Center Union's youth organization, EDIN.

He opposed the Zürich and London Agreement which led to the foundation of the Republic of Cyprus. Following clashes between the Greek and Turkish communities, his government sent a Greek army division to the island.

King Constantine II openly opposed Papandreou's government and there were frequent ultra rightist plots in the Army which destabilized the government. Finally the King engineered a split in the Center Union and in July 1965, known as apostasia or Iouliana, he dismissed the government following a dispute over control of the Ministry of Defense. After the April 1967 military coup by the Colonels' junta led by George Papadopoulos, Papandreou was arrested. Papandreou died under house arrest in November 1968. His funeral became the occasion for a massive anti - dictatorship demonstration. He is interred at the First Cemetery of Athens, alongside his son Andreas.

During the Junta and after his death he was often referred to affectionately as "ο Γέρος της δημοκρατίας" (o Géros tis dimokratías) - "the old man of democracy". Since his grandson George A. Papandreou entered politics, most Greek writers use Γεώργιος (Geórgios) to refer to the grandfather and the less formal Γιώργος (Giórgos) to refer to the grandson.

In 1965, the University of Belgrade awarded him a honorary doctorate.