<Back to Index>

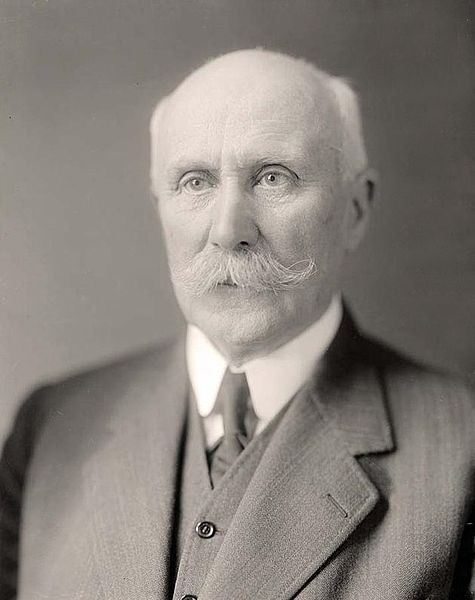

- Chief of the French State Marshal Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain, 1856

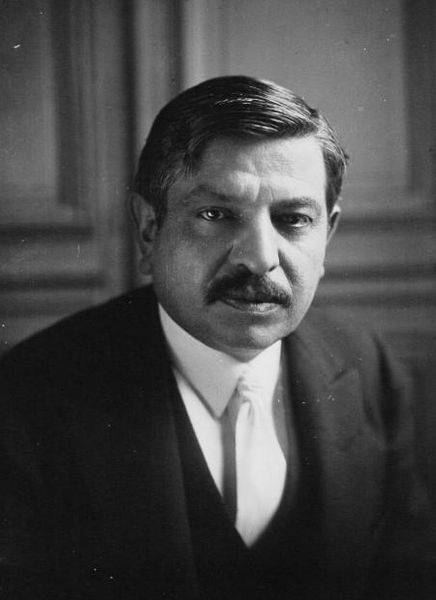

- Prime Minister of France Pierre Laval, 1883

PAGE SPONSOR

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), generally known as Philippe Pétain or Marshal Pétain (Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France, and was later Chief of State of Vichy France (Chef de l'État Français), from 1940 to 1944. Pétain, who was 84 years old in 1940, ranks as France's oldest head of state.

Because of his outstanding military leadership in World War I, particularly during the Battle of Verdun, he was viewed as a national hero in France. With the imminent French defeat in June 1940, Pétain was appointed Premier of France by President Lebrun at Bordeaux, and the Cabinet resolved to make peace with Germany. The entire government subsequently moved briefly to Clermont - Ferrand, then to the spa town of Vichy in central France. His government voted to transform the discredited French Third Republic into the French State, an authoritarian regime. As the war progressed, the government at Vichy collaborated with the Germans, who in 1942 finally occupied the whole of metropolitan France because of the threat from North Africa. Pétain's actions during World War II resulted in his conviction and death sentence for treason, which was commuted to life imprisonment by his former protégé Charles de Gaulle. In modern France he is remembered as an ambiguous figure, while pétainisme is a derogatory term for certain reactionary policies.

Pétain was born in Cauchy - à - la - Tour (in the Pas - de - Calais département in Northern France) in 1856. His father, Omer - Venant, was a farmer. His great - uncle, who was a Catholic priest, Father Abbe Lefebvre, had served in Napoleon’s Grande Armée and told the young Pétain tales of war and adventure of his campaigns from the peninsulas of Italy to the Alps in Switzerland. Highly impressed by the tales told by his uncle, his destiny was from then on determined. Pétain joined the French Army in 1876 and attended the St Cyr Military Academy in 1887 and the École Supérieure de Guerre (army war college) in Paris. His career progressed very slowly, as he rejected the French Army philosophy of the furious infantry assault, arguing instead that "firepower kills." His views were later proved to be correct during the First World War. He was promoted to captain in 1890 and major (Chef de Bataillon) in 1900. Unlike many French officers, he served mainly in mainland France, never Indochina or any of the African colonies, although he participated in the Rif campaign in Morocco. As colonel, he commanded the 33rd Infantry Regiment at Arras from 1911; the young lieutenant Charles de Gaulle, who served under him, later wrote that his "first colonel, Pétain, taught (him) the Art of Command." In the spring of 1914 he was given command of a brigade (still with the rank of colonel), but having been told he would never become a general, had bought a house pending retirement – he was already 58 years old.

At the end of August 1914 he was quickly promoted to brigadier general and given command of the 6th Division in time for the First Battle of the Marne; little over a month later, in October 1914, he was promoted again and became XXXIII Corps commander. After leading his corps in the spring 1915 Artois Offensive, in July 1915 he was given command of the Second Army, which he led in the Champagne Offensive that autumn. He acquired a reputation as one of the more successful commanders on the Western Front.

Pétain commanded the Second Army at the start of the Battle of Verdun in February 1916. During the battle he was promoted to Commander of Army Group Center, which contained a total of 52 divisions. Rather than holding down the same infantry divisions on the Verdun battlefield for months, akin to the German system, he rotated them out after only two weeks on the front lines. His decision to organize truck transport over the "Voie Sacrée" to bring a continuous stream of artillery, ammunition and fresh troops into besieged Verdun also played a key role in grinding down the German onslaught to a final halt in July 1916. In effect, he applied the basic principle that was a mainstay of his teachings at the École de Guerre (War College) before World War I: "le feu tue!" or "firepower kills!" — in this case meaning French field artillery, which fired over 15 million shells on the Germans during the first five months of the battle. Although Pétain did say "On les aura!" (an echoing of Joan of Arc, roughly: "We'll get them!"), the other famous quotation often attributed to him – "Ils ne passeront pas!" ("They shall not pass"!) – was actually uttered by Robert Nivelle who succeeded him in command of the Second Army at Verdun in May, 1916. At the very end of 1916, Nivelle was promoted over Pétain to replace Joseph Joffre as French Commander - in - Chief.

Because of his high prestige as a soldier's soldier, Pétain served briefly as Army Chief of Staff (from the end of April 1917). He then became Commander - in - Chief of the French army, replacing General Nivelle, whose Chemin des Dames offensive failed in April 1917, thereby provoking widespread mutinies in the French Army. Pétain put an end to the mutinies by selective punishment of ringleaders, but also by improving the soldiers' conditions (e.g., better food and shelter, and more leaves to visit their families), and promising that men's lives would not be squandered in fruitless offensives. Pétain conducted some successful but limited offensives in the latter part of 1917, unlike the British who stalled in an unsuccessful offensive at Passchendaele that autumn. Pétain, instead, held off from major French offensives until the Americans arrived in force on the front lines, which did not happen until the early summer of 1918. He was also waiting for the new Renault FT-17 tanks to be introduced in large numbers, hence his statement at the time: "I am waiting for the tanks and the Americans."

1918 saw major German offensives on the Western Front. The first of these, Operation Michael in March 1918, threatened to split the British and French forces apart, and, after he had threatened to retreat on Paris, Pétain came to the aid of the British and secured the front with forty French divisions. Pétain proved a capable opponent of the Germans both in defense and through counter attack.

The crisis led to the appointment of Ferdinand Foch as Allied Generalissimo, initially with powers to co-ordinate and deploy Allied reserves where he saw fit. The third offensive, "Blücher," in May 1918, saw major German advances on the Aisne, as the French Army commander (Humbert) ignored Pétain's instructions to defend in depth and instead allowed his men to be hit by the initial massive German bombardment.

By the time of the last German offensives, Gneisenau and the Second Battle of the Marne, Pétain was able to defend in depth and launch counter offensives, with the new French tanks and the assistance of the Americans.

Later in the year, Pétain was stripped of his right of direct appeal to the French government and requested to report to Foch, who increasingly assumed the co-ordination and ultimately the command of the Allied offensives.

Pétain was made Marshal of France in November 1918.

Pétain was a bachelor until his sixties, and famous for his womanizing. Women were said to find his piercing blue eyes especially attractive. At the opening of the Battle of Verdun he is said to have been fetched during the night from a Paris hotel by a staff officer who knew which mistress he could be found with. After the war Pétain married an old lover, "a particularly beautiful woman", Mme. Eugénie Hardon (1877 – 1962), on 14 September 1920. Hardon had been divorced from François de Hérain in 1914; although the couple were too old to have children (she had a son, Pierre de Hérain, from her first marriage), they remained married until the end of Pétain's life.

Pétain ended the war regarded "without a doubt, the most accomplished defensive tactician of any army" and "one of France’s greatest military heroes" and was made a Marshal of France at Metz by President Raymond Poincaré on 8 December 1918. He was subsequently summoned to be present at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on 28 June 1919, and was afterwards appointed to France’s "top military job as Vice Chairman of the revived 'Conseil Supérieur de la Guerre'".

He was encouraged to go into politics although he protested that he had little interest in running for an elected position. He nevertheless tried and failed to get himself elected President following the November 1919 elections. Pétain had placed before the government plans for a large tank and air force but "at the meeting of the 'Conseil Supérier de la Défense Nationale' of 12 March 1920 the Finance Minister, François Marsal, announced that although Pétain’s proposals were excellent they were unaffordable". In addition, Marsal announced reductions – in the army from fifty - five divisions to thirty, in the air force, and did not even mention tanks. It was left to the Marshals, Pétain, Joffre and Foch to pick up the pieces of their strategies. The General Staff, now under General Edmond Buat, began to think seriously about a line of forts along the frontier with Germany, and their report was tabled on 22 May 1922. The three Marshals supported this. The cuts in military expenditure meant that taking the offensive was now impossible and a defensive strategy was all they could have.

Pétain was appointed Inspector General of the Army in February 1922 and produced, in concert with the new Chief of the General Staff, General Marie - Eugéne Debeney, the new army manual entitled Provisional Instruction on the Tactical Employment of Large Units, which soon became known as 'the Bible'. On 3 September 1925 Pétain was appointed sole Commander - in - Chief of French Forces in Morocco to launch a major campaign against the Rif tribes, in concert with the Spanish Army, which was successfully concluded by the end of October. He was subsequently decorated, at Toledo, by King Alfonso XIII with the Spanish Medalla Militar.

In 1924 the National Assembly was elected on a platform of reducing the length of national service to one year, to which Pétain was almost violently opposed. In January 1926 the Chief of Staff, General Debeney, proposed to the 'Conseil' a "totally new kind of army. Only 20 infantry divisions would be maintained on a standing basis". Reserves could be called up when needed. The 'Conseil' had no option in the straitened circumstances but to agree. Pétain, of course, disapproved of the whole thing, pointing out that North Africa still had to be defended and in itself required a substantial standing army. But he recognized, after the new Army Organization Law of 1927, that the tide was flowing against him. He would not forget that the Radical leader, Édouard Daladier, even voted against the whole package, on the grounds that the Army was still too large.

On 5 December 1925, after the Locarno Treaty, the 'Conseil' demanded immediate action on a line of fortifications along the eastern frontier to counter the already proposed decline in manpower. A new Commission for this purpose was established, under Joseph Joffre, and called for reports. In July 1927 Pétain himself went to reconnoiter the whole area. He returned with a revised plan and the Commission then proposed two fortified regions. The Maginot Line, as it came to be called, (named after André Maginot, the former Minister of War) thereafter occupied a good deal of Pétain’s attention during 1928, when he also traveled extensively, visiting military installations up and down the country. Pétain had based his strong support for the Maginot Line on his own experience of the role played by the forts during the Battle of Verdun in 1916.

Captain Charles de Gaulle continued to be a protégé of Pétain throughout these years. He even named his eldest son after the Marshal before finally falling out over the authorship of a book he had said he had ghost - written for Pétain. Pétain finally retired as Inspector General of the Army, aged 75, in 1931, the year he was elected a Fellow of the Académie française.

In 1928 Pétain had supported the creation of an independent air force removed from the control of the army, and on 9 February 1931 he was appointed Inspector General of Air Defense. His first report on air defense, submitted in July that year, advocated increased expenditure. By 1932 economic skies had darkened and Édouard Herriot’s government had made "severe cuts in the defense budget..... orders for new weapons systems all but dried up". Summer maneuvers in 1932 and 1933 were cancelled due to lack of funds, and recruitment to the armed forces fell off. In the latter year General Weygand claimed that "the French Army was no longer a serious fighting force". Edouard Daladier’s new government retaliated against Weygand by reducing the number of officers and cutting military pensions and pay, arguing that such measures, apart from financial stringency, were in the spirit of the Geneva Disarmament Conference.

Political unease was sweeping the country, and on 6 February 1934 the Paris police fired on a group of rioters outside the Chamber of Deputies, killing 14 and wounding a further 236. President Lebrun invited 71 year old Doumergue to come out of retirement and form a new "government of national unity". Maréchal Pétain was invited, on 8 February, to join the new French cabinet as Minister of War, which he only reluctantly accepted after many representations. His important success that year was in getting Daladier’s previous proposal to reduce the number of officers repealed. He improved the recruitment program for specialists, and lengthened the training period by reducing leave entitlements. However Weygand reported to the Senate Army Commission that year that the French Army could still not resist a German attack. Generals Louis Franchet d'Espèrey and Hubert Lyautey (the latter suddenly died in July) added their names to the report. After the Autumn maneuvers, which Pétain had reinstated, a report was presented to Pétain that officers had been poorly instructed, had little basic knowledge, and no confidence. He was told, in addition, by Maurice Gamelin, that if the plebiscite in the Territory of the Saar Basin went for Germany it would be a serious military error for the French Army to intervene. Pétain responded by again petitioning the government for further funds for the army. During this period, he repeatedly called for a lengthening of the term of compulsory military service for draftees entering the military service, from two to three years, to no avail.

Pétain accompanied President Lebrun to Belgrade for the funeral of King Alexander, who had been assassinated on 6 October in Marseille by a Croatian nationalist. Here he met Hermann Göring and the two men reminisced about their experiences in The Great War. "When Goering returned to Germany he spoke admiringly of Pétain, describing him as a 'man of honor'". In November the Doumergue government fell. Pétain had previously expressed interest in being named Minister of Education (as well as of War), a role in which he hoped to combat what he saw as the decay in French moral values. Now, however, he refused to continue in Flandin’s (short lived) government as Minister of War and stood down – in spite of a direct appeal from Lebrun himself. Interestingly, at this moment an article appeared in Le Petit Journal, a popular newspaper, calling for Pétain as a candidate for a dictatorship. 200,000 readers responded to the paper’s poll. Pétain came first, with 47,000, ahead of Pierre Laval’s 31,000 votes. These two men traveled to Warsaw for the funeral of the Polish Marshal Pilsudski in May (and another cordial meeting with Goering).

He remained on the High Military Committee. Weygand had been at the British Army 1934 maneuvers at Tidworth in June and was appalled by what he had seen. Addressing the Committee on the 23rd, Pétain claimed that it would be fruitless to look for assistance to Britain in the event of a German attack. On 1 March 1935 Pétain’s famous article appeared in the Revue des deux mondes where he reviewed the history of the army since 1927 – 28. He criticized the Militia (reservist) system in France, and her lack of adequate air power and armor. This article appeared just five days before Adolf Hitler’s announcement of Germany’s new air force and a week before the announcement that Germany was increasing its army to 36 divisions.

On 26 April 1936 the General Election results showed 5.5 million votes for The Left against 4.5 million for The Right on an 84% turnout. On 3 May Pétain was interviewed in Le Journal where he launched into an attack on the Franco - Soviet Pact, on Communism in general (France had the largest Communist Party in Western Europe), and on those who allowed Communists intellectual responsibility. He said that France had lost faith in her destiny. Pétain was now in his 80th year.

Some have argued, that Pétain, as France's most senior soldier after Foch's death, should bear some responsibility for the poor state of French weaponry preparation before World War II. But Pétain was only one of many military and other men on a very large committee responsible for national defense, and interwar governments frequently cut military budgets. In addition, with the restrictions imposed on Germany by the Versailles Treaty there seemed no urgency for vast expenditure until the advent of Hitler. It is argued that whilst Pétain supported the massive use of tanks he saw them mostly as infantry support, leading to the fragmentation of the French tank force into many types of unequal value spread out between mechanized cavalry (such as the SOMUA S-35) and infantry support (mostly the Renault R35 tanks and the Char B1 bis). Modern infantry rifles and machine guns were not manufactured, with the sole exception of a light machine - rifle, the Mle 1924. The French heavy machine gun was still the Hotchkiss M1914, a capable weapon but decidedly obsolete compared to the new automatic weapons of German infantry. A modern infantry rifle was adopted in 1936 but very few of these MAS-36 rifles had been issued to the troops by 1940. A well tested French semiautomatic rifle, the MAS 1938 – 39, was ready for adoption but it never reached the production stage until after World War II as the MAS 49. As to French artillery it had, basically, not been modernized since 1918. The result of all these failings is that the French Army had to face the invading enemy in 1940, with the dated weaponry of 1918. Pétain had been made, briefly, Minister of War in 1934, thus ministerially responsible for French military, aviation and the Navy as well. Yet his short period of total responsibility could not reverse 15 years of inactivity and constant cutbacks. The War Ministry was hamstrung between the wars and proved unequal to the tasks before them. French aviation entered the War in 1939 without even the prototype of a bomber airplane capable of reaching Berlin and coming back. French industrial efforts in fighter aircraft were dispersed among several firms (Dewoitine, Morane - Saulnier and Marcel Bloch), each with its own model. On the naval front, France had purposely overlooked building modern aircraft carriers and focused instead on four new conventional battleships, not unlike the German Navy.

On 24 May 1940, the invading Germans pushed back the French Army. General Maxime Weygand expressed his fury at British retreats and the unfulfilled promise of British fighter aircraft. He and Pétain regarded the military situation as hopeless. Paul Reynaud subsequently stated before a parliamentary commission of inquiry in December 1950 that he said, as Premier of France to Pétain on that day that they must seek an armistice. Weygand said that he was in favor of saving the French army and that he “wished to avoid internal troubles and above all anarchy”. Churchill’s man in Paris, Spears, kept up continual pressure on the French, and on 31 May he met with Pétain and threatened France with not only a blockade, but bombardment of the French ports if an armistice was agreed. Spears reported that Pétain did not respond immediately but stood there "perfectly erect, with no sign of panic or emotion. He did not disguise the fact that he considered the situation catastrophic. I could not detect any sign in him of broken morale, of that mental wringing of hands and incipient hysteria noticeable in others". Pétain later remarked to Reynaud about this threat, saying "your ally now threatens us".

On 5 June, following the fall of Dunkirk, there was a Cabinet reshuffle, and Prime Minister Reynaud brought Pétain, Weygand, and the newly promoted Brigadier General de Gaulle, whose 4th Armored Division had launched one of the few French counterattacks the previous month, into his War Cabinet, hoping that the trio might instill a renewed spirit of resistance and patriotism in the French Army. On 8 June, Paul Baudouin dined with Chautemps, and both declared that the war must end. Paris was now threatened, and the government was preparing to depart, although Pétain was opposed to such a move. During a cabinet meeting that day, Reynaud argued for an armistice, as he was worried about England. Pétain replied that "the interests of France come before those of England. England got us into this position, let us now try to get out of it".

On 10 June, the government left Paris for Tours. Weygand, the Commander - in - Chief, now declared that “the fighting had become meaningless”. He, Baudouin, and several members of the government were already set on an armistice. On 11 June, Churchill flew to the Château du Muguet, at Briar, near Orleans, where he put forward first his idea of a Breton redoubt, to which Weygand replied that it was just a "fantasy". Churchill then said the French should consider "guerrilla warfare" until the Americans came into the war, to which several cabinet members asked "when might that be" and received no reply. Pétain then replied that it would mean the destruction of the country. Churchill then said the French should defend Paris and repeated Clemenceau’s words "I will fight in front of Paris, in Paris, and behind Paris". To this, Churchill subsequently reported, Pétain replied quietly and with dignity that he had in those days a strategic reserve of sixty divisions; now, there was none. Making Paris into a ruin would not affect the final event. The following day, the cabinet met and Weygand again called for an armistice. He referred to the danger of military and civil disorder and the possibility of a Communist uprising in Paris. Pétain and Minister of Information Prouvost urged the Cabinet to hear Weygand out because "he was the only one really to know what was happening".

Churchill returned to France on the 13th. Paul Baudouin met his plane and immediately spoke to him of the hopelessness of further French resistance. Reynard, then, put the cabinet’s armistice proposals to Churchill, who replied that "whatever happened, we would level no reproaches against France". At that day’s Cabinet meeting, Pétain read out a draft proposal to the Cabinet where he spoke of "the need to stay in France, to prepare a national revival, and to share the sufferings of our people. It is impossible for the Government to abandon French soil without emigrating, without deserting. The duty of the Government is, come what may, to remain in the country, or it could not longer be regarded as the government". Several ministers were still opposed to an armistice, and Weygand immediately lashed out at them for even leaving Paris. Like Pétain, he said he would never leave France.

The government moved to Bordeaux, where French Governments had fled German invasions in 1870 and 1914, on 14 June. Parliament, both Senate and Chamber, were also there and immersed themselves in the armistice debate. Reynard’s ambiguous position was becoming seriously compromised. Admiral Darlan was by now in the armistice camp also. Reynard proposed an alternative compromise: Complete surrender, and the army (after laying down its arms) to leave the country and continue the fight from abroad. Weygand exploded and he and Pétain both said that such a capitulation would be dishonorable. The Cabinet was now split almost evenly. Camille Chautemps said the only way to get agreement was to ask the Germans what their terms for an armistice would be and the cabinet voted 13 – 6 in agreement.

The next day, Roosevelt’s reply to President Lebrun’s requests for assistance came with only vague promises and saying that it was impossible for the President to do anything without Congress.

After lunch, President Albert Lebrun received two telegrams from the British saying they would only agree to an armistice if the French fleet was immediately sent to British ports. In addition, the British Government offered joint nationality for Frenchmen and Englishmen in a Franco - British Union. Reynaud and five ministers thought these proposals acceptable. The others did not, seeing the offer as insulting and a device to make France subservient to Great Britain, in a kind of extra Dominion. Reynaud gave up and asked President Lebrun to accept his resignation as Prime Minister and nominated Maréchal Pétain in his place.

A new Cabinet was formed in the normal way, and, at midnight on the 15th, Baudouin was asking the Spanish Ambassador to submit to Germany a request to cease hostilities at once and for Germany to make known its peace terms. At 12:30 am, Maréchal Pétain made his first broadcast to the French people.

"The enthusiasm of the country for the Maréchal was tremendous. He was welcomed by people as diverse as Claudel, Gide and Mauriac, and also by the vast mass of untutored Frenchmen who saw him as their savior." General de Gaulle, no longer in the Cabinet, had arrived in London on the 16th and made a call for resistance from there, on the 18th, with no legal authority whatsoever from his government, a call that was heeded by comparatively few.

Cabinet and Parliament still argued between themselves on the question of whether or not to retreat to North Africa. On 18 June, Edouard Herriot (who would later be a – discredited – prosecution witness at Pétain's trial) and Jeanneney, the Presidents of the two Chambers of Parliament, as well as Lebrun said they wanted to go. Pétain said he was not departing. On the 20th, a delegation from the two chambers came to Pétain to protest at the proposed departure of President Lebrun. The next day, they went to Lebrun himself. In the event, only 26 deputies and 1 senator headed for Africa, among them Georges Mandel, Pierre Mendès France and the former Popular Front Education Minister, Jean Zay, all of whom had Jewish backgrounds. Pétain broadcast again to the French people on that day.

On 22 June, France signed an armistice with Germany that gave Germany control over the north and west of the country, including Paris and all of the Atlantic coastline, but left the rest, around two - fifths of France's prewar territory, unoccupied. Paris remained the de jure capital. On 29 June, the French Government moved to Clermont - Ferrand where the first discussions of constitutional changes were mooted, with Pierre Laval having personal discussions with President Lebrun, who had, in the event, not departed France. On 1 July, the government, finding Clermont too cramped, moved to the spa town of Vichy, at Baudouin’s suggestion, the empty hotels there being more suitable for the government ministries.

The Chamber of Deputies and Senate, meeting together as a "Congrès," held an emergency meeting on 10 July to ratify the armistice. At the same time, the draft constitutional proposals were tabled. The Presidents of both Chambers spoke and declared that constitutional reform was necessary. The Congress voted 569 - 80 (with 18 abstentions) to grant the Cabinet the authority to draw up a new constitution, effectively "voting the Third Republic out of existence". Nearly all French historians, as well as all postwar French governments, consider this vote to be illegal; not only were several deputies and senators not present, but the constitution explicitly stated that the republican form of government could not be changed. On the next day, Pétain formally assumed near absolute powers as "Head of State", though he stated at the time "this is not ancient Rome and I have no wish to be Caesar".

Pétain was reactionary by temperament and education, and quickly began blaming the Third Republic and its endemic corruption for the French defeat. His regime soon took on clear authoritarian - and in some cases, fascist - characteristics. The republican motto of "Liberté, égalité, fraternité" was replaced with "Travail, famille, patrie" ("Work, family, fatherland"). Fascistic and revolutionary conservative factions within the new government used the opportunity to launch an ambitious program known as the "National Revolution," which rejected much of the former Third Republic's secular and liberal traditions in favor of an authoritarian, paternalist, Catholic society. Pétain, among others, took exception to the use of the inflammatory term "revolution" to describe an essentially conservative movement, but otherwise participated in the transformation of French society from "Republic" to "State." He added that the new France would be "a social hierarchy... rejecting the false idea of the natural equality of men."

The new government immediately used its new powers to order harsh measures, including the dismissal of republican civil servants, the installation of exceptional jurisdictions, the proclamation of antisemitic laws, and the imprisonment of opponents and foreign refugees. Censorship was imposed, and freedom of expression and thought were effectively abolished with the reinstatement of the crime of "felony of opinion."

The regime organized a "Légion Française des Combattants," which included "Friends of the Legion" and "Cadets of the Legion," groups of those who had never fought but were politically attached to the new regime. Pétain championed a rural, Catholic France that spurned internationalism. As a retired military commander, he ran the country on military lines. He and his government collaborated with Germany and even produced a legion of volunteers to fight in Russia. Pétain's government was nevertheless internationally recognized, notably by the USA, at least until the German occupation of the rest of France.

Neither Pétain nor his successive deputies, Pierre Laval, Pierre - Étienne Flandin or Admiral François Darlan, gave significant resistance to requests by the Germans to indirectly aid the Axis Powers. Yet, when Hitler met Pétain at Montoire in October 1940 to discuss the French government's role in the new European Order, the Marshal "listened to Hitler in silence. Not once did he offer a sympathetic word for Germany." Furthermore, France remained neutral as a state, albeit opposed to the Free French. After the British attack on 2 July 1940 Mers el Kébir and Dakar, the French government became increasingly Anglophobic and took the initiative to collaborate with the occupiers. Pétain accepted the government's creation of a collaborationist armed militia (the Milice) under the command of Joseph Darnand, who, along with German forces, led a campaign of repression against French resistance ("Maquis"), notably its Communist factions.

The honors that Darnand acquired included SS - Major. Pétain admitted Darnand into his government as Secretary of the Maintenance of Public Order (Secrétaire d'État au Maintien de l'Ordre). In August 1944, Pétain made an attempt to distance himself from the crimes of the militia by writing Darnand a letter of reprimand for the organization's "excesses". The latter wrote a sarcastic reply, telling Pétain that he should have "thought of this before".

Pétain's government acquiesced to the Axis forces demands for large supplies of manufactured goods and foodstuffs, and also ordered French troops in France's colonial empire (in Dakar, Syria, Madagascar, Oran and Morocco) to defend sovereign French territory against any aggressors, Allied or otherwise.

Pétain's motives are a topic of wide conjecture. Winston Churchill had spoken to M. Reynaud during the impending fall of France, saying of Pétain, "...he had always been a defeatist, even in the last war [World War I]."

On 11 November 1942, German forces invaded the unoccupied zone of Southern France in response to the Allies' Operation Torch landings in North Africa and Admiral François Darlan's agreement to support the Allies. Although the French government nominally remained in existence, civilian administration of almost all France being under it, Pétain became nothing more than a figurehead, as the Germans had negated the pretense of an "independent" government at Vichy. Pétain however remained popular and engaged on a series of visits around France as late as 1944, when he arrived in Paris on 28 April in what Nazi propaganda newsreels described as a "historic" moment for the city. Vast crowds cheered him in front of the Hotel de Ville and in the streets.

After the liberation of France, on 7 September 1944, Pétain and other members of the French cabinet at Vichy were relocated by the Germans to Sigmaringen in Germany, where they became a government - in - exile until April 1945. Pétain, however, having been forced to leave France, refused to participate and the 'government commission' became headed by Fernand de Brinon. In a note dated 29 October 1944, Pétain forbade de Brinon to use the Marshal's name in any connection with this new government, and, on 5 April 1945, Pétain wrote a note to Hitler expressing his wish to return to France. No reply ever came. However, on his birthday 19 days later, he was taken to the Swiss border. Two days later he crossed into the French frontier.

De Gaulle wrote later that Pétain's decision to return to France to face his accusers in person was "certainly courageous". De Gaulle's provisional government placed Pétain on trial, which took place from 23 July to 15 August 1945, for treason. He remained silent through most of the proceedings, after an initial statement that denied the right of the High Court, as presently constituted, to try him. De Gaulle himself was later to criticize the trial, saying: "Too often, the discussions took on the appearance of a partisan trial, sometimes even a settling of accounts, when the whole affair should only have been treated from the point of view of national defense and independence."

At the end of Pétain's trial, although the three judges proposed Pétain's acquittal on all the charges laid against him, the jury convicted him and passed a death sentence by a majority of one. On account of Pétain's age the Court asked that the sentence not be carried out. De Gaulle, who was President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic at the end of the war, commuted the sentence to life imprisonment, on the grounds of Pétain's age and recognition of his World War I contributions.

After conviction, the Court stripped Pétain of all military ranks and honors, except Pétain's distinction as a Marshal of France. (Maréchal is a distinction conferred by special personal law passed by the French Parliament. Due to separation of powers principles, the French Court could not usurp powers reserved for Parliament; courts cannot act in a legislative manner. In the Pétain case the Court did not have the authority to reverse the law passed by Parliament conferring Pétain a Marshal of France.)

Fearing riots at the announcement of the sentence, de Gaulle ordered Pétain immediately transported on de Gaulle's private aircraft to Fort du Portalet in the Pyrenees, where he remained from 15 August to 16 November 1945. The government later imprisoned Pétain in the Fort de Pierre - Levée citadel on the Île d'Yeu, an island off the French Atlantic coast.

Now in his nineties, Pétain's physical and mental condition deteriorated to where he required round - the - clock nursing care. He died at Île d'Yeu on July 23, 1951, at the age of 95. His body is buried at a marine cemetery (Cimetière communal de Port - Joinville) near the prison. Calls are sometimes made to re-inter his remains in the grave prepared for him at Verdun.

In 1973, Pétain's coffin was stolen from the Île d'Yeu Cemetery by extremists who demanded that French president Georges Pompidou consent to Pétain's reburial at Douaumont Cemetery among the war dead. One week later, Pétain's coffin was found in a garage in Paris, and those responsible for the grave robbery were arrested. Pétain was ceremoniously reburied with a Presidential wreath on his coffin, but as before, on the Île d'Yeu island.

Mount Pétain, nearby Pétain Creek and Pétain Falls forming the Pétain Basin on the Continental Divide in the Canadian Rockies were named after him in 1919; summits with the names of other French generals are nearby: Foch, Cordonnier, Mangin, Castelnau and Joffre.

Pierre Laval (28 June 1883 – 15 October 1945) was a French politician. He was four times President of the council of ministers of the Third Republic, twice consecutively.

Following France's surrender and Armistice with Germany in 1940, he served twice in the Vichy Regime as head of government. He signed orders permitting the deportation of foreign Jews from French soil to the Nazi death camps.

After Liberation (1945), Laval was arrested by the French government under General Charles de Gaulle, found guilty of high treason, and executed by firing squad. The controversy surrounding his political activities has generated a dozen biographies.

Laval was born 28 June 1883 at Châteldon, Puy - de - Dôme, in the northern part of Auvergne. His father worked in the village as a café proprietor, butcher and postman; he also owned a vineyard and horses. Laval was educated at the village school in Châteldon. At age 15, he was sent to a Paris lycée to study for his baccalauréat. Returning south to Lyon, he spent the next year reading for a degree in zoology.

Laval joined the Socialists in 1903, when he was living in Saint - Étienne, 62 km southwest of Lyon.

"I was never a very orthodox socialist", he said in 1945, "by which I mean that I was never much of a Marxist. My socialism was much more a socialism of the heart than a doctrinal socialism... I was much more interested in men, their jobs, their misfortunes and their conflicts than in the digressions of the great German pontiff."

Laval returned to Paris in 1907 at the age of 24. He was called up for military service and, after serving in the ranks, was discharged for varicose veins. In April 1913 he said: "Barrack - based armies are incapable of the slightest effort, because they are badly trained and, above all, badly commanded." He favored abolition of the army and replacement by a citizens' militia.

During this period, Laval became familiar with the left wing doctrines of George Sorel and Hubert Lagardelle. In 1909, he turned to the law.

Shortly after becoming a member of the Paris bar, he married the daughter of a Dr. Claussat and set up a home in Paris with his new wife. Their only child, a daughter, was born in 1911. Although Laval's wife came from a political family, she never participated in politics. Laval was devoted to his family, a fact even his enemies admitted.

The years before the First World War were characterized by labor unrest, and Laval defended strikers, trade unionists and left wing agitators against government attempts to prosecute them. At a trade union conference, Laval said:

I am a comrade among comrades, a worker among workers. I am not one of those lawyers who are mindful of their bourgeois origin even when attempting to deny it. I am not one of those high brow attorneys who engage in academic controversies and pose as intellectuals. I am proud to be what I am. A lawyer in the service of manual laborers who are my comrades, a worker like them, I am their brother. Comrades, I am a manual lawyer.

In April 1914, as fear of war swept the nation, the Socialists and Radicals geared up their electoral campaign in defense of peace. Their leaders were Jean Jaurès and Joseph Caillaux. The Bloc des Gauches (Leftist Bloc) denounced the law passed in July 1913 extending compulsory military service from two to three years. The Confédération générale du travail trade union sought Laval as Socialist candidate for the Seine, a Paris suburb. He won. The Radicals, with the support of Socialists, held the majority in the French Chamber of Deputies. Together they hoped to avert war. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on 28 June 1914 and of Jaurès on 31 July 1914 shattered those hopes. Laval's brother, Jean, died in the first months of the war.

Laval and 2,000 others were listed by the military in the Carnet B, a compilation of potentially subversive elements who might hinder mobilization. In the name of national unity, Minister of the Interior Jean - Louis Malvy, despite pressure from chiefs of staff, refused to have anyone apprehended. Laval remained true to his pacifist convictions during the war. In December 1915, Jean Longuet, grandson of Karl Marx, proposed to Socialist parliamentarians that they communicate with socialists of other states, hoping to press governments into a negotiated peace. Laval signed on, but the motion was defeated.

With France's resources geared for war, goods were scarce or overpriced. On 30 January 1917, in the National Assembly Laval called upon the Supply Minister Édouard Herriot to deal with the inadequate coal supply in Paris. When Herriot said, "If I could, I would unload the barges myself", Laval retorted "Do not add ridicule to ineptitude." The words delighted the assembly and attracted the attention of George Clemenceau, but left the relationship between Laval and Herriot permanently strained.

Laval scorned the conduct of the war and the poor supply of troops in the field. When mutinies broke out after General Robert Nivelle's offensive of April 1917 at Chemin des Dames, he spoke in defense of the mutineers. When Marcel Cachin and Marius Moutet returned from St. Petersburg in June 1917 with the invitation to a socialist convention in Stockholm, Laval saw a chance for peace. In an address to the Assembly, he urged the chamber to allow a delegation to go: "Yes, Stockholm, in response to the call of the Russian Revolution.... Yes, Stockholm, for peace.... Yes, Stockholm the polar star." The request was denied.

The hope of peace in spring 1917 was overwhelmed by discovery of traitors, some real, some imagined, as with Malvy. Because he had refused to arrest Frenchmen on the Carnet B, Malvy became a suspect. Laval's "Stockholm, étoile polaire" speech had not been forgotten. Many of Laval's acquaintances, the publishers of the anarchist Bonnet rouge, and other pacifists were arrested or interrogated. Though Laval frequented pacifist circles – it was said that he was acquainted with Leon Trotsky – the authorities did not pursue him. His status as a deputy, his caution, and his friendships protected him. In November 1917, Clemenceau offered him a post in government, but the Socialist Party by then refused to enter any government. Laval toed the party line, but he questioned the wisdom of such a policy in a meeting of the Socialist members of parliament.

In 1919 a conservative wave swept the Bloc National into control. Laval was not reelected. The Socialists' record of pacifism, their opposition to Clemenceau, and anxiety arising from the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia contributed to their defeat.

The General Confederation of Labour (CGT), with 2,400,000 members, launched a general strike in 1920, which petered out as thousands of workers were laid off. In response, the government sought to dissolve the CGT. Laval, with Joseph Paul - Boncour as chief counsel, defended the union's leaders, saving the union by appealing to the ministers Théodore Steeg (interior) and Auguste Isaac (commerce and industry).

Laval's relations with the Socialist Party drew to an end. The last years with the Socialist caucus in the chamber combined with the party's disciplinary policies eroded Laval's attachment to the cause. With the Bolshevik victory in Russia the party was changing; at the Congress of Tours in December 1920, the Socialists split into two ideological components: the French Communist Party (SFIC later PCF), inspired by Moscow, and the more moderate French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO). Laval let his membership lapse, not taking sides as the two factions battled over the legacy of Jean Jaurès.

In 1923 Aubervilliers in northern Paris needed a mayor. As a former deputy of the constituency, Laval was an obvious candidate. To be eligible for election, Laval bought farmland, Les Bergeries. Few were aware of his defection from the Socialists. Laval was also asked by the local SFIO and Communist Party to head their lists. Laval chose to run under his own list, of former socialists he convinced to leave the party and work for him. This was an independent Socialist Party of sorts that only existed in Aubervilliers. In a four way race Laval won in the second round. He remained mayor of Aubervilliers until just before his death.

Laval won over those he defeated by cultivating personal contacts. He developed a network among the humble and the well - to - do in Aubervilliers, and with mayors of neighboring towns. He was the only independent politician in the suburb. This let him avoid getting the ideological war between socialists and communists.

In the 1924 legislative elections, the SFIO and the Radicals formed a national coalition known as the Cartel des Gauches. Laval headed a list of independent socialists in the Seine. The cartel won and Laval regained a seat in the National Assembly. His first act was to bring back Joseph Caillaux, former member of the National Assembly and once the star of the Radical Party. Clemenceau had had Caillaux arrested toward the end of the war for collusion with the enemy. He spent two years in prison and lost his civic rights. Laval stood for Caillaux's pardon and won. Caillaux became an influential patron.

Laval's reward for support of the cartel was appointment as Minister of Public Works in the government of Paul Painlevé in April 1925. Six months later, the government collapsed. Laval from then on belonged to the club of former ministers from which new ministers were drawn. Between 1925 and 1926 Laval participated three more times in governments of Aristide Briand, once as under - secretary to the premier and twice as Minister of Justice (garde des sceaux). When he first became Minister of Justice, Laval abandoned his law practice to avoid conflict of interest.

Laval's momentum was frozen after 1926 through a reshuffling of the cartel majority orchestrated by the Radical - Socialist mayor and deputy of Lyon, Édouard Herriot. Founded in 1901, the Radical Party became the hinge faction of the Third Republic. Its support or defection often meant survival or collapse of governments. Through this latest swing, Laval was excluded from the direction of France for four years. Author Gaston Jacquemin suggested that Laval chose not to partake in a Herriot government, which he judged incapable of handling the financial crisis. 1926 marked the definitive break between Laval and the left, but he maintained friends on the left.

In 1927 Laval was elected Senator for the Seine, withdrawing from and placing himself above the political battles for majorities in the National Assembly. He longed for a constitutional reform to strengthen the executive branch and eliminate political instability, the flaw of the Third Republic.

On 2 March 1930 Laval returned as Minister of Labor in the second André Tardieu government. Tardieu and Laval knew each other from the days of Clemenceau, which developed into mutual appreciation. Tardieu needed men he could trust: his previous government had collapsed a little over a week earlier because of the defection of the minister of Labor, Louis Loucheur. But, when the Radical Socialist Camille Chautemps failed to form a viable government, Tardieu was called back.

During 1927 – 30 Laval began to accumulate the sizable personal fortune which later gave rise to charges that he had used his political position to line his own pockets. "I have always thought", he wrote to the examining magistrate on 11 September 1945, "that a soundly based material independence, if not indispensable, gives those statesmen who possess it a much greater political independence." Until 1927 his principal source of income had been his fees as a lawyer and in that year they totaled 113,350 francs, according to his income tax returns. Between August 1927 and June 1930, however, he undertook large scale investments in various enterprises, totaling 51 million francs. Not all this money was his own, it came from a group of financiers who had the backing of an investment trust, the Union Syndicale et Financière and two banks, the Comptoir Lyon Allemand and the Banque Nationale de Crédit.

Two of the investments which Laval and his backers acquired were provincial newspapers, Le Moniteur du Puy - de - Dôme and its associated printing works at Clermont - Ferrand, and the Lyon Républicain. The circulation of the Moniteur stood at 27,000 in 1926 before Laval took it over. By 1933, it had more than doubled to 58,250. Thereafter it fell away again and never surpassed its earlier peak. Profits varied, but over the seventeen years of his control, Laval obtained some 39 million francs in income from the paper and the printing works combined, and the renewed plant was valued at 50 million francs, which led the high court expert to say with some justification that it had been "an excellent affair for him."

More than 150,000 textile workers were on strike, and violence was feared. As Minister of Public Works in 1925, Laval had ended the strike of mine workers. Tardieu hoped he could do the same as Minister of Labor. The conflict was settled without bloodshed. Socialist politician Léon Blum, never one of Laval's allies, conceded that Laval's "intervention was skillful, opportune and decisive."

Social insurance had been on the agenda for ten years. It had passed the Chamber of Deputies, but not the Senate, in 1928. Tardieu gave Laval until May Day to get the project through. The date was chosen to stifle the agitation of Labor Day. Laval's first effort went into clarifying the muddled collection of texts. He then consulted employer and labor organizations. Laval had to reconcile the divergent views of Chamber and Senate. "Had it not been for Laval's unwearying patience", Laval's associate Tissier wrote, "an agreement would never have been achieved", In two months Laval presented the Assembly a text which overcame its original failure. It met the financial constraints, reduced the control of the government, and preserved the choice of doctors and their billing freedom. The Chamber and the Senate passed the law with an overwhelming majority.

When the bill had passed its final stages, Tardieu described his Minister of Labor as "displaying at every moment of the discussion as much tenacity as restraint and ingenuity."

Tardieu's government ultimately proved unable to weather the Oustric Affair. After the failure of the Oustric Bank, it appeared that members of the government had improper ties to it. The scandal involved Minister of Justice Raoul Péret, and Under - Secretaries Henri Falcoz and Eugène Lautier. Though Tardieu was not involved, on 4 December 1930, he lost his majority in the Senate. President Gaston Doumergue called on Louis Barthou to form a government, but Barthou failed. Doumergue turned to Laval, who fared no better. The following month the government formed by Théodore Steeg floundered. Doumergue renewed his offer to Laval. On 27 January 1931 he successfully formed his first government.

In the words of Léon Blum, the Socialist opposition was amazed and disappointed that the ghost of Tardieu's government reappeared within a few weeks of being defeated with Laval, "like a night bird surprised by the light" at its head. Laval's nomination as premier led to speculation that Tardieu, the new agriculture minister, held the real power in the Laval Government. Laval thought highly of Tardieu and Briand, and applied policies in line with theirs. Laval was not Tardieu's mouthpiece. Ministers who formed the Laval government were in great part those who had formed Tardieu governments but that was a function of the composite majority Laval could find at the National Assembly. Raymond Poincaré, Aristide Briand and Tardieu before him had offered ministerial posts to Herriot's Radicals, but to no avail.

Besides Briand, André Maginot, Pierre - Étienne Flandin, Paul Reynaud, Laval brought in as his advisors, friends such as Maurice Foulon from Aubervilliers, and Pierre Cathala, whom he knew from his days in Bayonne and who had worked in Laval's Labor ministry. Cathala began as Under - Secretary of the Interior and became Minister of the Interior in January 1932. Blaise Diagne of Senegal, the first African deputy, had joined the National Assembly at the same time as Laval in 1914. Laval invited Diagne to join his cabinet as under - secretary to the colonies, making him the first Black African in a French government. Laval called on financial experts such as Jacques Rueff, Charles Rist and Adéodat Boissard. André François - Poncet was brought in as under - secretary to the premier and then as ambassador to Germany. Laval's government included an economist, Claude - Joseph Gignoux, when economists in government service were rare.

France in 1931 was unaffected by the world economic crisis. Laval declared on embarking for America on 16 October 1931, "France remained healthy thanks to work and savings." Agriculture, small industry and protectionism were the bases of France's economy. The conservative policy of contained wages and limited social services, allowed France the largest gold reserves in the world after the United States. France reaped the benefit of devaluation of the franc orchestrated by Poincaré, which made French products competitive on the world market. In the whole of France, there were 12,000 people unemployed.

Laval and his cabinet considered the economy and gold reserves as means to diplomatic ends. Laval left to visit London, Berlin and Washington. He attended conferences on the world crisis, war reparations and debt, disarmament and the gold standard.

In 1931, Austria underwent a banking crisis when its largest bank, the Creditanstalt, was revealed to be nearly bankrupt, threatening a worldwide financial crisis. World leaders began negotiating the terms for an international loan to Austria's central government in order to sustain its financial system; however, Laval blocked the proposed package for nationalistic reasons, demanding that France receive a series of diplomatic concessions in exchange for its support, including renunciation of a prospective German - Austrian customs union. This proved to be fatal for the negotiations, which ultimately fell through. As a result, the Creditanstalt declared bankruptcy on May 11, 1931, precipitating a crisis that quickly spread to other nations. Within four days, bank runs in Budapest were underway, and the bank failures began spreading to Germany and Britain, among others.

The Hoover Moratorium of 1931, a proposal made by American President Herbert Hoover to freeze all intergovernmental debt for a one year period, was, according to author and political advisor McGeorge Bundy, "the most significant action taken by an American president for Europe since Woodrow Wilson's administration." The reality was that the United States had enormous stakes in Germany: long term German borrowers owed the United States private sector more than $1.25 billion; the short term debt neared $1 billion. By comparison, the entire United States national income in 1931 was just $54 billion. To put it into perspective, authors Walter Lippmann and William O. Scroggs stated in The United States in World Affairs, An Account of American Foreign Relations, that "the American stake in Germany's government and private obligations was equal to half that of all the rest of the world combined."

The proposed moratorium would also benefit Great Britain's investment in Germany's private sector making more likely the repayment of those loans while the public indebtedness was frozen. It certainly was in Hoover's interest to offer aid to an ailing British economy in light of Great Britain's indebtedness to the United States. France, on the other hand, had a relatively small stake in Germany's private debt but a huge interest in German reparations; and payment to France would be compromised under Hoover's moratorium.

Already difficult to accept on the face of it was further complicated by ill timing, perceived collusion between the US, Great Britain and Germany and a breach of the Young Plan. Such breach could only be approved by the National Assembly and thus the survival of the Laval Government rested on the legislative body's approval of the moratorium. Seventeen days elapsed between the proposal and the vote of confidence of the French legislators. That delay was blamed for the lack of success of the Hoover Moratorium. The U.S. Congress only approved it in December of that year.

The Hoover Moratorium was the opening shot to a year of personal and direct diplomacy which took Laval to London, Berlin and the United States. While internally he was able to accomplish much, his international efforts were short in results. British Premier Ramsay McDonald and Foreign Secretary Arthur Anderson — preoccupied by internal political divisions and the collapse of the Pound Sterling – were unable to help. German Chancellor Heinrich Brüning and Foreign Minister Julius Curtius, both eager for Franco - German reconciliation, were under siege on all quarters: they faced a very weak economy which made meeting government payroll a weekly miracle, and private bankruptcies and constant lay offs had the communists on a short fuse. On the other end of the political spectrum the German army was actively spying on the Brüning cabinet and feeding information to the Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten and the National Socialists, effectively freezing any overtures towards France.

In the United States the conference between Hoover and Laval was an exercise in mutual frustration. Hoover's plan for a reduced military had been rebuffed – albeit gently. A solution to the Danzig corridor had been retracted. The concept of introducing silver standard for the countries that went off the gold standard was disregarded as a frivolous proposal by Laval and Albert - Buisson. Hoover thought it might have helped "Mexico, India, China and South America", but Laval dismissed the silver solution as an inflationary proposition adding that "it was cheaper to inflate paper."

Laval did not get a security pact, without which the French would never consider disarmament, nor did he obtain an endorsement for the political moratorium. The promise to match any reduction of German reparations with a decrease of the French debt was not put in the communiqué. What was stated in the joint statement was the attachment of France and the United States to the gold standard. The two governments also agreed that the Banque de France and the Federal Reserve would consult each other before the transfer of gold. This was welcome news after the run on American gold in the preceding weeks. In light of the financial crisis, they further agreed to review the economic situation of Germany before the Hoover moratorium ran its course.

These were no doubt meagre political results. The Hoover - Laval encounter, however, had an impact. The American and French press was smitten with Laval. His optimism was such a contrast to his grim - sounding international contemporaries that Time magazine made him their 1931 Man of the Year, an honor never bestowed on a Frenchman before, following Mohandas K. Gandhi and preceding Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The second Cartel des gauches (Left - Wing Cartel) was driven from power by the riots of 6 February 1934, staged by fascist, monarchist and other far right groups. (These groups had contacts with some conservative politicians, among whom were Laval and Marshal Philippe Pétain.) Laval became Minister of Colonies in the new right wing government of Gaston Doumergue. In October, Foreign Minister Louis Barthou was assassinated; Laval succeeded him, holding that office until 1936.

At this time, Laval was opposed to Germany, the "hereditary enemy" of France. He pursued anti - German alliances with Benito Mussolini's Italy and Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union. He met with Mussolini in Rome, and they signed the Franco – Italian Agreement of 1935 on 4 January. The agreement ceded parts of French Somaliland to Italy and allowed Italy a free hand in Abyssinia, in exchange for support against any German aggression. Laval denied that he gave Mussolini a free hand in Abyssinia, he even wrote to Mussolini on the subject. In April 1935, Laval persuaded Italy and Great Britain to join France in the Stresa Front against German ambitions in Austria.

In June 1935, he became Prime Minister as well. In October 1935, Laval and British foreign minister Samuel Hoare proposed a "realpolitik" solution to the Abyssinia Crisis. When leaked to the media in December, the Hoare - Laval Pact was widely denounced as appeasement to Mussolini. Laval was forced to resign on 22 January 1936, and was driven completely out of ministerial politics.

The victory of the Popular Front in 1936 meant that Laval had a left wing government as a target for his media.

During the phoney war, Laval's attitude towards the conflict reflected a cautious ambivalence. He was on record as saying that although the war could have been avoided by diplomatic means, it was now up to the government to prosecute it with the utmost vigor.

On 9 June 1940, the Germans were advancing on a front of more than 250 kilometres (160 mi) in length across the entire width of France. As far as General Maxime Weygand was concerned, "if the Germans crossed the Seine and the Marne, it was the end."

Simultaneously, Marshal Philippe Pétain was increasing the pressure upon Prime Minister Paul Reynaud to call for an armistice. During this time Laval was in Châteldon. On 10 June, in view of the German advance, the government left Paris for Tours. Weygand had informed Reynaud: "the final rupture of our lines may take place at any time." If that happened "our forces would continue to fight until their strength and resources were extinguished. But their disintegration would be no more than a matter of time."

Weygand had avoided using the word armistice, but it was on the minds of all those involved. Only Reynaud was in opposition. During this time Laval had left Châteldon for Bordeaux, where his daughter nearly convinced him of the necessity of going to the United States. Instead, it was reported that he was sending "messengers and messengers" to Pétain.

As the Germans occupied Paris, Pétain was asked to form a new government. To everyone's surprise, he produced a list of his ministers, convincing proof that he had been expecting the president's summons and he had prepared for it. Laval's name was on the list as Minister of Justice. When informed of his proposed appointment, Laval's temper and ambitions became apparent as he ferociously demanded of Pétain, despite the objections of more experienced men of government, that he be made Minister of Foreign Affairs. Laval realized that only through this position could he effect a reversal of alliances and bring himself to favor with Nazi Germany, the military power he viewed as the inevitable victor. In the face of Laval's wrath, dissenting voices acquiesced and Laval became Minister of Foreign Affairs.

One result of these events was that Laval was later able to claim that he was not part of the government that requested the armistice. His name did not appear in the chronicles of events until June when he began to assume a more active role in criticizing the government's decision to leave France for North Africa.

Although the final terms of the armistice were harsh, the French colonial empire was left untouched and the French government was allowed to administer the occupied and unoccupied zones. The concept of "collaboration" was written into the Armistice Convention, before Laval joined the government. The French representatives who affixed their signatures to the text accepted the term.

Article III. In the occupied areas of France, the German Reich is to exercise all the rights of an occupying power. The French government promises to facilitate by all possible means the regulations relative to the exercise of this right, and to carry out these regulations with the participation of the French administration. The French government will immediately order all the French authorities and administrative services in the occupied zone to follow the regulations of the German military authorities and to collaborate with the latter in a correct manner.

When Laval was included in Pétain's cabinet as minister of state, he began the work for which he would be remembered: the emulation of the totalitarian regime of Germany, the taking up of the cause of fascism, the destruction of democracy, and the dismantling of the Third Republic.

In October 1940, Laval understood collaboration more or less in the same sense as Pétain. For both, to collaborate meant to give up the least possible in order to get the most. Laval, in his role of go-between, was forced to be in constant touch with the German authorities, to shift ground, to be wily, to plan ahead. All this, under the circumstances, drew more attention to him than to the Marshal and made him appear to many Frenchmen as "the agent of collaboration"; to others, he was "the Germans' man".

The meetings between Pétain and Adolf Hitler, and between Laval and Hitler, are often used as showing the collaboration of the French leaders and the Nazis. In fact the results of Montoire (24 – 26 October) were a disappointment for both sides. Hitler wanted France to declare war on the British, and the French wanted improved relations with her conqueror. Neither happened. Virtually the only concession the French obtained was the so-called 'Berlin protocol' of 16 November, which provided release of certain categories of French prisoners of war.

In November, Laval made a number of pro - German actions on his own, without consulting with his colleagues. The most notorious examples concerned turning over to the Germans the RTB Bor copper mines and the Belgian gold reserves. His post - war justification, apart from a denial that he acted unilaterally, was that the French were powerless to prevent the Germans from gaining something they were clearly so eager to obtain.

These actions by Laval were a factor in his dismissal on 13 December, when Pétain asked all the ministers to sign a collective letter of resignation during a full cabinet meeting. Laval did so thinking it was a device to get rid of M. Belin, the Minister of Labor. He was therefore stunned when the Marshal announced, "the resignations of MM. Laval and Ripert are accepted."

That evening, Laval was arrested and driven by the police to his home in Châteldon. The following day, Pétain announced his decision to remove Laval from the government. The reason for Laval's dismissal lies in the fundamental incompatibility between him and Pétain. Laval's methods of working appeared slovenly to the Marshal's precise military mind, and he showed a marked lack of deference, instanced by his habit of blowing cigarette smoke in Pétain's face, and in doing so he aroused not only Pétain's anger, but that of his cabinet colleagues as well.

On 27 August 1941, several top Vichyites including Laval attended a review of the Légion des Volontaires Français (LVF), a collaborationist militia. Paul Collette, a disgruntled ex-member of the Croix - de - Feu, attacked the reviewing stand; he shot and wounded Laval (and also Marcel Déat, another prominent collaborationist). Laval soon recovered from the injury.

Laval returned to power in April 1942. Laval had been in power for a mere two months when he was faced with the decision of providing forced workers to Germany. Germany was short of skilled labor due to its need for troop replacements on the Russian front. Unlike the other occupied countries, France was technically protected by the armistice, and her workers could not be simply rounded up and transported to Germany. However, in the occupied zone, the Germans used intimidation and control of raw materials to create unemployment and thus reasons for French laborers to volunteer to work in Germany. German officials demanded from Laval that more than 300,000 skilled workers should be immediately sent to factories in Germany. Laval delayed and then countered by offering to send one worker for the return of one French soldier being held captive in Germany. The proposal was sent to Hitler, with a compromise being reached; one prisoner of war to be repatriated for every three workers arriving in Germany.

The role of Laval in the deportation of Jews to death camps has been hotly debated by both his accusers and defenders. When ordered to have all Jews in France rounded up to be transported to Poland, Laval negotiated a compromise, allowing only those Jews who were not French citizens to be forfeited to the control of Germany. It has been estimated that by the end of the war the Germans had wiped out ninety percent of the Jewish population of the other occupied countries but in France fifty per cent of the pre-war French and foreign Jewish population, with perhaps ninety per cent of the purely French Jewish population still remaining alive. However, Laval went beyond the orders given to him by the Germans, by including Jewish children under 16 in the deportations. The Germans had given him permission to spare children under 16. In his book Churches and the Holocaust, Mordecai Paldiel claims that when Protestant leader Martin Boegner visited Laval in order to remonstrate, Laval claimed that he had ordered children to be deported along with their parents because families should not be separated and "children should remain with their parents". According to Paldiel, when Boegner argued that the children would almost certainly die, Laval replied "not one [Jewish child] must remain in France". Yet, Sarah Fishman claims that Laval also attempted to prevent Jewish children gaining visas to America, arranged by the American Friends Service Committee. He was not so much committed to expelling Jewish children from France, as making sure they reached Nazi camps. Neither Paldiel nor Fishman offer valid citations for what they have written, so it must be considered as hearsay.

More and more the insoluble dilemma of collaboration faced Laval and his chief of staff, Jean Jardin. Laval had to maintain Vichy's authority to prevent Germany from installing a Quisling Government made up of French Nazis. Compromise after compromise loaded Laval with the accusation he was nothing more than an agent of Germany.

In 1943, Laval became the nominal leader of the newly created Milice, though its actual leader was Secretary General Joseph Darnand.

When Operation Torch, the landings of Allied forces in North Africa, began, Germany occupied all of France. Hitler continued to ask whether the French government was prepared to fight at his side, wanting Vichy to declare war against Britain. Laval and Pétain agreed to maintain a firm refusal. During this time and the D-Day landings, Laval was in a struggle against ultra - collaborationist ministers.

In a broadcast speech on D-Day he appealed to the nation:

You are not in the war. You must not take part in the fighting. If you do not observe this rule, if you show proof of indiscipline, you will provoke reprisals the harshness of which the government would be powerless to moderate. You would suffer, both physically and materially, and you would add to your country's misfortunes. You will refuse to heed the insidious appeals, which will be addressed to you. Those who ask you to stop work or invite you to revolt are the enemies of our country. You will refuse to aggravate the foreign war on our soil with the horror of civil war.... At this moment fraught with drama, when the war has been carried on to our territory, show by your worthy and disciplined attitude that you are thinking of France and only of her."

A few months later, he was arrested by the Germans and transported to Belfort. In view of the speed of the Allied advance, on 7 September, what was left of the Vichy government was moved from Belfort to the castle of Sigmaringen in Germany. By April 1945 U.S. General George S. Patton's army was near Sigmaringen so the Vichy ministers were forced to seek their own salvation. Laval received permission to enter Spain, only to be returned to Germany after a few months. The United States authorities immediately took him and his wife into custody, and turned them over to the Free French. They were flown to Paris to be imprisoned at Fresnes, Val - de - Marne. Madame Laval was later released; Pierre Laval remained in prison to be tried as a traitor.

Two trials were to be held. Although it had its faults, the Pétain trial permitted the presentation and examination of a vast amount of pertinent material. As to the second trial, a number of scholars including Robert Paxton and Geoffrey Warner are of the opinion that Laval's own trial illustrated nothing but the inadequacies of the judicial system and the poisonous political atmosphere of that purge - trial era.

During his imprisonment pending the verdict of his treason trial, Laval wrote his only book, his posthumously published Diary, which his daughter, Josée de Chambrun smuggled out of the prison page by page.

Laval firmly believed that he would be able to convince his fellow countrymen that he had been acting in their best interests all along. "Father - in - law wants a big trial which will illuminate everything", René de Chambrun told Laval's lawyers: "If he is given time to prepare his defence, if he is allowed to speak, to call witnesses and to obtain from abroad the information and documents which he needs, he will confound his accusers."

"Do you want me to tell you the set - up?" Laval asked one of his lawyers on 4 August. "There will be no pre - trial hearings and no trial. I will be condemned – and got rid of – before the elections."

Laval's trial began at 1:30 pm on Thursday, 4 October 1945. He was charged with plotting against the security of the State and intelligence (collaboration) with the enemy. He had three defence lawyers (Jaques Baraduc, Albert Naud and Yves - Frédéric Jaffré). None of his lawyers had ever met him before. He saw most of Jaffré, who sat with him, talked, listened and took down notes that he wanted to dictate. Baraduc, who quickly became convinced of Laval's innocence, kept contact with the Chambruns and at first shared their conviction that Laval would be acquitted or at most receive a sentence of temporary exile. Naud, who had been a member of the Resistance, believed Laval to be guilty and urged him to plead that he had made grave errors but had acted under constraint. Laval would not listen to him; he was convinced that he was innocent and could prove it. "He acted", said Naud, "as if his career, not his life, was at stake."

All three of his lawyers declined to be in court to hear the reading of the formal charges because "We fear that the haste which has been employed to open the hearings is inspired, not by judicial preoccupations, but motivated by political considerations." In lieu of attending the hearing they sent letters stating the shortcomings and asked to be discharged from the task of defending Laval.

The court carried on without them. The president of the court, Pierre Mongibeaux announced that the trial must be completed before the general election — scheduled for 21 October. The trial proceeded with the tone being set with Mongibeaux and Mornet, the public prosecutor, unable to control constant hostile outbursts from the jury. These occurred as increasingly heated exchanges between Mongibeaux and Laval became louder and louder. On the third day, Laval's three lawyers were with him as the President of the Bar Association had advised them to resume their duties.

After the adjournment, Mongibeaux announced that the part of the interrogation dealing with the charge of plotting against the security of the state was concluded and that he now proposed to deal with the charge of intelligence (collaboration) with the enemy. "Monsieur le Président", Laval replied, "the insulting way in which you questioned me earlier and the demonstrations in which some members of the jury indulged show me that I may be the victim of a judicial crime. I do not want to be an accomplice; I prefer to remain silent." Mongibeaux thereupon called the first of the prosecution witnesses, but they had not expected to give evidence so soon and none were present. Mongibeaux therefore adjourned the hearing for the second time so that they could be located. When the court reassembled half an hour later, Laval was no longer in his place.

Although Pierre - Henri Teitgen, the Minister of Justice in Charles de Gaulle's cabinet, personally appealed to Laval's lawyers to have him attend the hearings, he declined to do so. Teitgen freely confirmed the conduct of Mongibeaux and Mornet, professing he was unable to do anything to curb them. The trial continued without the accused, ending with Laval being sentenced to death. His lawyers were turned down when they requested a re-trial.

The execution was fixed for the morning of 15 October. Laval attempted to cheat the firing squad by taking poison from a phial which had been stitched inside the lining of his jacket since the war years. He did not intend, he explained in a suicide note, that French soldiers should become accomplices in a "judicial crime". The poison, however, was so old that it was ineffective, and repeated stomach pumpings revived Laval.

Laval requested his lawyers to witness his execution. He was shot shouting "Vive la France!". Shouts of "Murderers!" and "Long live Laval!" were apparently heard from the prison. Laval's widow declared: "It is not the French way to try a man without letting him speak", she told an English newspaper, "That's the way he always fought against – the German way."