<Back to Index>

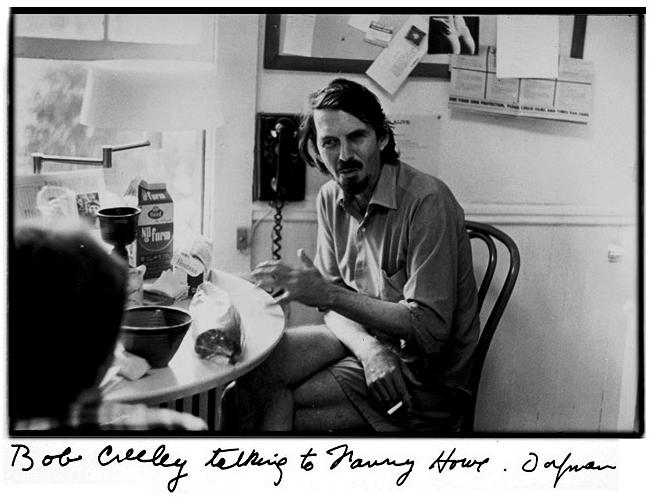

- Poet and Writer Robert Creeley, 1926

PAGE SPONSOR

Robert Creeley (May 21, 1926 – March 30, 2005) was an American poet and author of more than sixty books. He is usually associated with the Black Mountain poets, though his verse aesthetic diverged from that school's. He was close with Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, Allen Ginsberg, John Wieners and Ed Dorn. He served as the Samuel P. Capen Professor of Poetry and the Humanities at State University of New York at Buffalo. In 1991, he joined colleagues Susan Howe, Charles Bernstein, Raymond Federman, Robert Bertholf, and Dennis Tedlock in founding the Poetics Program at Buffalo. Creeley lived in Waldoboro, Maine, Buffalo, New York, and Providence, Rhode Island, where he taught at Brown University. He was a recipient of the Lannan Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award.

Creeley was born in Arlington, Massachusetts, and grew up in Acton. He was raised by his mother with one sister, Helen. At the age of four, he lost his left eye. He attended the Holderness School in New Hampshire. He entered Harvard University in 1943, but left to serve in the American Field Service in Burma and India in 1944 - 1945. He returned to Harvard in 1946, but eventually took his BA from Black Mountain College in 1955, teaching some courses there as well. When Black Mountain closed in 1957, Creeley moved to San Francisco, where he met Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. He later met and befriended Jackson Pollock in the Cedar Tavern in New York City.

He was a chicken farmer briefly before becoming a teacher. The farm was in Littleton, New Hampshire. He was 23. The story goes that he wrote to Cid Corman whose radio show he heard on the farm, and Corman had him read on the show, which is how Charles Olson first heard of Creeley.

From 1951 to 1955, Creeley and his wife, Ann, lived with their three children on the Spanish island of Mallorca. They went there at the encouragement of their friends Martin Seymour - Smith and his wife, Janet. There they started Divers Press and published works by Paul Blackburn, Robert Duncan, Charles Olson, and others. Creeley wrote about half of his published prose while living on the island, including a short story collection, The Gold Diggers, and a novel, The Island. He said that Martie and Janet are represented by Artie and Marge in the novel, The Island. He traveled between Mallorca and his teaching position at Black Mountain College in 1954 and 1955. They also saw to the printing of some issues of Origin and Black Mountain Review on Mallorca because the printing costs were significantly lower there.

An MA from the University of New Mexico followed in 1960. He began his academic career by teaching at the prestigious Albuquerque Academy starting in around 1958 until about 1960 or 1961. In 1957, he met Bobbie Louise Hawkins; they lived together, common law marriage, until 1975. They had two children, Sarah and Katherine. He dedicated his book For Love to Bobbie. Creeley read at the 1963 Vancouver Poetry Festival and at the 1965 Berkeley Poetry Conference. Afterward, he wandered about a bit before settling into the English faculty of "Black Mountain II" at the University at Buffalo in 1967. He would stay at this post until 2003, when he received a post at Brown University. From 1990 to 2003, he lived with his family in Black Rock, in a converted firehouse at the corner of Amherst and East Streets . At the time of his death, he was in residence with the Lannan Foundation in Marfa, Texas.

He first received fame in 1962 from his poetry collection For Love. He would go on to win the Bollingen Prize, among others, and held the position of the New York State Poet Laureate from 1989 until 1991. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2003.

In 1968, he signed the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest” pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the Vietnam War.

In his later years he was an advocate of, and a mentor to, many younger poets, as well as to others outside of the poetry world. He went to great lengths to be supportive to many people regardless of any poetic affiliation. Being responsive appeared to be essential to his personal ethics, and he seemed to take this responsibility extremely seriously, in both his life and his craft. In his later years, when he became well known, he would go to lengths to make strangers, who approached him as a well known author, feel comfortable. In his last years, he used the Internet to keep in touch with many younger poets and friends.

Robert Creeley died at sunrise on March 30, 2005, in Odessa, Texas, of complications from pneumonia. His death resulted in an outpouring of grief and appreciation from many in the poetry world. He is buried in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was scheduled to visit Albuquerque Academy, where he held a teaching post, 10 days after the day he died, to help celebrate their 50th anniversary.

According to Arthur L. Ford in his book Robert Creeley (1978), "Creeley has long been aware that he is part of a definable tradition in the American poetry of this century, so long as 'tradition' is thought of in general terms and so long as it recognizes crucial distinctions among its members. The tradition most visible to the general public has been the Eliot - Stevens tradition supported by the intellectual probings of the New Critics in the 1940s and early 1950s. Parallel to that tradition has been the tradition Creeley identifies with, the Pound - Olson - Zukofsky - Black Mountain tradition, what M.L. Rosenthal [in his book The New Poets: American and British Poetry Since World War II (1967)] calls 'The Projectivist Movement'." This "movement" Rosenthal derives from Olson's essay on "Projective Verse".

Le Fou, Creeley's first book, was published in 1952, and since then, according to his publisher, barely a year passed without a new collection of poems. The 1983 entry, titled Mirrors, had some tendencies toward concrete imagery. It was hard for many readers and critics to immediately understand Creeley's reputation as an innovative poet, for his innovations were often very subtle; even harder for some to imagine that his work lived up to the Black Mountain tenet — which he articulated to Charles Olson in their correspondence, and which Olson popularized in his essay "Projective Verse," -- that "form is never more than an extension of content," for his poems were often written in couplet, triplet, and quatrain stanzas that break into and out of rhyme as happenstance appears to dictate. An example is "The Hero," from Collected Poems, also published in 1982 and covering the span of years from 1945 to 1975.

"The Hero" is written in variable isoverbal ("word - count") prosody; the number of words per line varies from three to seven, but the norm is four to six. Another technique to be found in this piece is variable rhyme — there is no set rhyme scheme, but some of the lines rhyme and the poem concludes with a rhymed couplet. All of the stanzas are quatrains, as in the first two:

THE HERO

- Each voice which was asked

- spoke its words, and heard

- more than that, the fair question,

- the onerous burden of the asking.

- And so the hero, the

- hero! stepped that gracefully

- into his redemption, losing

- or gaining life thereby.

Despite these obviously formal elements various critics continue to insist that Creeley wrote in "free verse", but most of his forms were strict enough so that it is a question whether it can even be maintained that he wrote in forms of prose. This particular poem is without doubt verse - mode, not prose - mode. M.L. Rosenthal in his The New Poets quoted Creeley's "'preoccupation with a personal rhythm in the sense that the discovery of an external equivalent of the speaking self is felt to be the true object of poetry,'" and went on to say that this speaking self serves both as the center of the poem's universe and the private life of the poet. "Despite his mask of humble, confused comedian, loving and lovable, he therefore stands in his own work's way, too seldom letting his poems free themselves of his blocking presence". When he used imagery, Creeley could be interesting and effective on the sensory level.

In an essay titled "Poetry: Schools of Dissidents," the academic poet Daniel Hoffman wrote, in The Harvard Guide to Contemporary American Writing which he edited, that as he grew older, Creeley's work tended to become increasingly fragmentary in nature, even the titles subsequent to For Love: Poems 1950 - 1960 hinting at the fragmentation of experience in Creeley's work: Words, Pieces, A Day Book. In Hoffman's opinion, "Creeley has never included ideas, or commitments to social issues, in the repertoire of his work; his stripped down poems have been, as it were, a proving of Pound's belief in 'technique as the test of a man's sincerity.'"

Jazz bassist Steve Swallow released the albums Home (ECM, 1979) and So There (ECM, 2005) featuring poems by Creeley put to music.

Posthumous publications of Creeley's work are ongoing. Some of these include the two volume edition of his Collected Poems, which has already appeared. Forthcoming is The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley edited by Rod Smith, Kaplan Harris and Peter Baker for University of California Press.