<Back to Index>

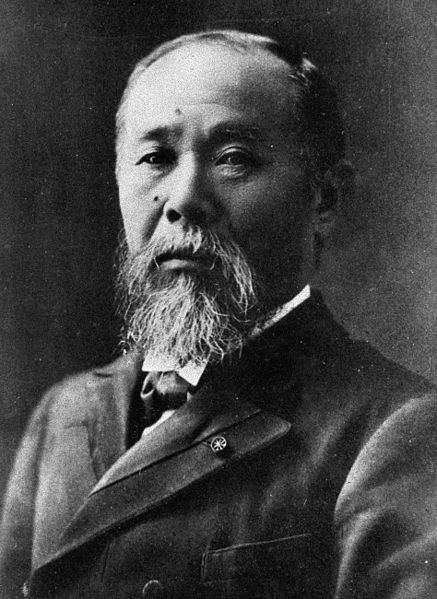

- 1st Prime Minister of Japan Itō Hirobumi, 1841

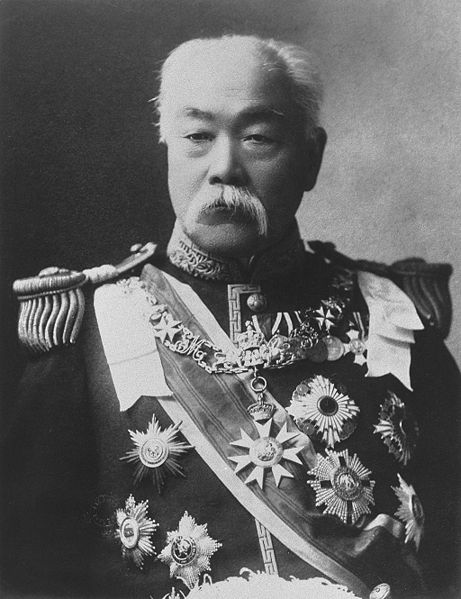

- 4th Prime Minister of Japan Matsukata Masayoshi, 1835

PAGE SPONSOR

Prince Itō Hirobumi, GCB (伊藤 博文, 16 October 1841 – 26 October 1909, also called Hirofumi / Hakubun and Shunsuke in his youth) was a samurai of Chōshū domain, Japanese statesman, four time Prime Minister of Japan (the 1st, 5th, 7th and 10th), genrō and Resident General of Korea. Itō was assassinated by Korean nationalist An Jung - geun. The politician, intellectual, and author Suematsu Kenchō was Itō’s son - in - law, having married his second daughter, Ikuko.

Itō was born as the son of Hayashi Jūzō. He was originally named Hayashi Risuke. His father Hayashi Jūzō was the adopted son of Mizui Buhei who was an adopted son of Itō Yaemon's family, a lower class samurai from Hagi, Chōshū domain (present day Yamaguchi prefecture). Mizui Buhei was renamed to Itō Naoemon. Mizui Jūzō took the name Itō Jūzō, and Hayashi Risuke was renamed to Itō Shunsuke at first, then Itō Hirobumi. He was a student of Yoshida Shōin at the Shōka Sonjuku and later joined the Sonnō jōi movement (“to revere the Emperor and expel the barbarians”), together with Kido Takayoshi. Itō was chosen to be one of the Chōshū Five who studied at University College London in 1863, and the experience in Great Britain convinced him of the necessity of Japan adopting Western ways.

In 1864, Itō returned to Japan with fellow student Inoue Kaoru to attempt to warn the Chōshū clan against going to war with the foreign powers (the Bombardment of Shimonoseki) over the right of passage through the Straits of Shimonoseki. At that time, he met Ernest Satow for the first time, later a lifelong friend.

After the Meiji Restoration, Itō was appointed governor of Hyōgo Prefecture, junior councilor for Foreign Affairs, and sent to the United States in 1870 to study Western currency systems. Returning to Japan in 1871, he established Japan's taxation system. Later that year, he was sent on the Iwakura Mission around the world as vice envoy extraordinary, during which he won the confidence of Ōkubo Toshimichi one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration.

In 1873, Itō was made a full councilor, Minister of Public Works, and in 1875 chairman of the first Assembly of Prefectural Governors. He participated in the Osaka Conference of 1875. After Ōkubo's assassination, he took over the post of Home Minister and secured a central position in the Meiji government. In 1881 he urged Ōkuma Shigenobu to resign, leaving himself in unchallenged control.

Itō went to Europe in 1882 to study the constitutions of those countries, spending nearly 18 months away from Japan. While working on a constitution for Japan, he also wrote the first Imperial Household Law and established the Japanese peerage system (kazoku) in 1884.

In 1885, he negotiated the Convention of Tientsin with Li Hongzhang, normalizing Japan's diplomatic relations with Qing Dynasty China.

In 1885, based on European ideas, Itō established a cabinet system of government, replacing the Daijō - kan as the decision making state organization, and on December 22, 1885, he became the first prime minister of Japan.

On April 30, 1888, Itō resigned as prime minister, but headed the new Privy Council to maintain power behind the scenes. In 1889, he also became the first genro. The Meiji Constitution was promulgated in February 1889. He had added to it the references to the kokutai or "national polity" as the justification of the emperor's authority through his divine descent and the unbroken line of emperors, and the unique relationship between subject and sovereign. This stemmed from his rejection of some European notions as unfit for Japan, as they stemmed from European constitutional practice and Christianity.

He remained a powerful force while Kuroda Kiyotaka and Yamagata Aritomo, his political nemeses, were prime ministers.

During Itō’s second term as prime minister (August 8, 1892 – August 31, 1896), he supported the First Sino - Japanese War and negotiated the Treaty of Shimonoseki in March 1895 with his ailing foreign minister Mutsu Munemitsu. In the Anglo - Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation of 1894, he succeeded in removing some of the onerous unequal treaty clauses that had plagued Japanese foreign relations since the start of the Meiji period.

During Itō’s third term as prime minister (January 12 – June 30, 1898), he encountered problems with party politics. Both the Jiyūtō and the Shimpotō opposed his proposed new land taxes, and in retaliation, Itō dissolved the Diet and called for new elections. As a result, both parties merged into the Kenseitō, won a majority of the seats, and forced Itō to resign. This lesson taught Itō the need for a pro-government political party, so he organized the Rikken Seiyūkai in 1900. Itō's womanizing was a popular theme in editorial cartoons and in parodies by contemporary comedians, and was used by his political enemies in their campaign against him.

Itō returned to office as prime minister for a fourth term from October 19, 1900, to May 10, 1901, this time facing political opposition from the House of Peers. Weary of political back stabbing, he resigned in 1901, but remained as head of the Privy Council as the premiership alternated between Saionji Kimmochi and Katsura Tarō. Itō received an honorary doctorate from Yale University around this time.

It was during his terms as Prime Minister that he invited Professor George Trumbull Ladd of Yale University to serve as a diplomatic adviser to promote mutual understanding between Japan and the United States.

It was because of his series of lectures he delivered in Japan

revolutionizing its educational methods, that he was the first foreigner

to receive the Second Class honor (conferred by the Meiji Emperor in 1907) and the Third Class honor (conferred by The Meiji Emperor in 1899), Orders of the Rising Sun. He later wrote a book on his personal experiences in Korea and with Resident General Itō. Following his assassination, half of Hirobumi's ashes were buried in a Tokyo Temple and a monument was erected to him.

In November 1905, following the Russo - Japanese War, the Japan – Korea Treaty of 1905 was signed between the Empire of Japan and the Empire of Korea, making Korea a Japanese protectorate. After the treaty had been signed, Itō became the first Resident General of Korea on 21 December 1905. In 1907, he urged Emperor Gojong to abdicate in favor of his son Sunjong and secured the Japan - Korea Annexation Treaty of 1907, giving Japan its authorities to control Korea's internal affairs. Itō’s position, however, was nuanced. He was firmly against Korea falling into China or Russia's sphere of influence, which would cause a grave threat to Japan's national security. But, he was actually against the annexation, advocating instead that Korea should remain as a protectorate. When the cabinet eventually voted for annexing Korea, he insisted and proposed a delay, hoping that the annexation decision could be reversed in the future. His political nemesis came when politically influential Imperial Japanese Army, led by Yamagata Aritomo, whose main faction was advocating annexation forced Itō to resign on 14 June 1909. His assassination is believed to have accelerated the path to the Japan - Korea Annexation Treaty.

Itō proclaimed

that if East Asians do not closely cooperate with each other, all three

would fall to the victims of Western imperialism. Gojong and the Joseon

government believing in these claims, agreed to help the Japanese

military.

However, the opinion of Joseon soon turned against Japan as many

Japanese actions were considered to be too brutal and barbaric including

confiscation of lands and drafting civilians for forced labor, even

executing those that resisted. Ironically his assassin An Jung - geun

strongly believed in a union of the three East Asian nations in order

to counter and fight off the "White Peril", being the European countries

engaged in colonialism, restoring peace in the region. With his

political and diplomatic skills backed by the Japanese military's strong

presence, Itō laid the foundation for Japan's colonization of Korea and

expansion into Manchuria, China and Russia during the World War II.

Itō arrived at the Harbin Railway Station on October 26, 1909 for a

meeting with Vladimir Kokovtsov, a Russian representative in Manchuria.

When he arrived and proceeded to meet his Russian colleague, An Jung -

geun, a Korean nationalist and independence activist, fired six shots at

him. Three of those shots hit Itō in the chest and he died shortly

thereafter.

A portrait of Itō Hirobumi was on the Series C 1,000 yen note of Japan from 1963 until a new series was issued in 1984. His former house is preserved as a museum near the Shoin Jinja, in Hagi city, Yamaguchi prefecture. However, the actual structure was Itō’s second home, formerly located in Shinagawa, Tokyo.

The publishing company Hakubunkan was named after Itō, based on an alternate pronunciation of his given name.

According to the Annals of Sunjong, Gojong said on 28 October 1909 that Itō Hirobumi made great efforts to develop civilization. However, it should be noted that the Annals of Gojong and of Sujong are regarded as unreliable by the National Institute of Korean History, given that these two Annals or sillocks are not designated as National Treasures of South Korea and UNESCO's World Heritage unlike other silloks due to Japanese influence exerted on them. They consider these last two documents are regarded as a falsification of history.

The 1979 North Korean film, An Jung - gun Shoots Ito Hirobumi, is an account of Hirobumi's assassination from the North Korean perspective. The 1973 South Korean film Femme Fatale: Bae Jeong-ja is the life of Itō's adopted daughter Bae Jeong-ja (1870 – 1950).

Prince Matsukata Masayoshi (松方 正義, 25 February 1835 – 2 July 1924) was a Japanese politician and the 4th (6 May 1891 – 8 August 1892) and 6th (18 September 1896 - 12 January 1898) Prime Minister of Japan.

Matsukata was born into a samurai family in Kagoshima, Satsuma province (present day Kagoshima Prefecture). At the age of 13, he entered the Zoshikan, the Satsuma domain's Confucian academy, where he studied the teachings of Wang Yangming, which stressed loyalty to the Emperor. He started his career as a bureaucrat of the Satsuma domain. In 1866, he was sent to Nagasaki to study western science, mathematics and surveying. Matsukata was highly regarded by Ōkubo Toshimichi and Saigō Takamori, who used him as their liaison between Kyoto and the domain government in Kagoshima.

Knowing that war was coming between Satsuma and the Tokugawa, Matsukata purchased a ship available in Nagasaki for use in the coming conflict. This ship was then given the name Kasuga. The leaders of Satsuma felt the ship was best used as cargo vessel and so Matsukata resigned his position as captain of the ship he had purchased. Just a few months later the Kasuga did become a warship and it fought in the Boshin War against the Tokugawa ships. At the time of the Meiji Restoration, he helped maintain order in Nagasaki after the collapse of the Tokugawa bakufu. In 1868, Matsukata was appointed governor of Hita Prefecture (part of present day Ōita Prefecture) by his friend Okubo who was the powerful minister of the interior for the new Meiji government.

As governor Matsukata instituted a number of reforms including road building, starting the port of Beppu,

and building a successful orphanage. His ability as an administrator

was noted in Tokyo and after two years he was summoned to the capital.

Matsukata moved to Tokyo in 1871 and began work on drafting laws for the Land Tax Reform of 1873 - 1881. Under the new system:

- a taxpayer paid taxes with money instead of rice

- taxes were calculated based on the price of estates, not the amount of the agricultural product produced, and

- tax rates were fixed at 3% of the value of estates and an estate holder was obliged to pay those taxes.

The new tax system was radically different from the traditional tax gathering system, which required taxes to be paid with rice varied according to location and the amount of rice produced. The new system took some years to be accepted by the Japanese people.

Matsukata became Home Minister in 1880. In the following year, when Ōkuma Shigenobu was expelled in a political upheaval, he became Finance Minister. The Japanese economy was in a crisis situation due to rampant inflation. Matsukata introduced a policy of fiscal restraint that resulted in what has come to be called the "Matsukata Deflation." The economy was eventually stabilized, but the resulting crash in commodity prices caused many smaller landholders to lose their fields to money lending neighbors. Matsukata also established the Bank of Japan in 1882, which has issued paper money instead of the government since that time. When Itō Hirobumi was appointed the first Prime Minister of Japan in 1885, he appointed Matsukata to be the first Finance Minister under the new Meiji Constitution.

Matsukata also sought to protect Japanese industry from foreign competition, but was restricted by the unequal treaties. The unavailability of protectionist devices probably benefited Japan in the long run, as it enabled Japan to develop its export industries. The national government also tried to create government industries to produce particular products or services. Lack of funds forced the government to turn these industries over to private businesses which in return for special privileges agreed to pursue the government's goals. This arrangement led to the rise of the zaibatsu system.

Matsukata served as finance minister in seven of the first 10

cabinets, and for 18 of the 20 year period from 1881 - 1901. He also wrote

Articles 62 - 72 of the Meiji Constitution of 1889.

Matsukata followed Yamagata Aritomo as Prime Minister from 6 May 1891 - 8 August 1892, and followed Ito Hirobumi as Prime Minister from 18 September 1896 - 12 January 1898, during which times he concurrently also held office as finance minister.

One issue of his term in office was the Black Ocean Society, which operated with the support of certain powerful figures in the government and in return was powerful enough to demand concessions from the government. They demanded and received promises of a strong foreign policy from the 1892 Matsukata Cabinet.

Matsukata successively held offices as president of the Japanese Red Cross Society, privy councilor, gijokan, member of the House of Peers, and Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal of Japan. Later, he was given the title of prince and genrō.

- 1884 - Count

- 1906 - Grand Cordons of the Order of the Chrysanthemum

- 1907 - Marquess

- 1916 - Collars of the Order of the Chrysanthemum

- 1922 - Duke

Matsukata was named an Honorary Knight Grand Cross of Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG).

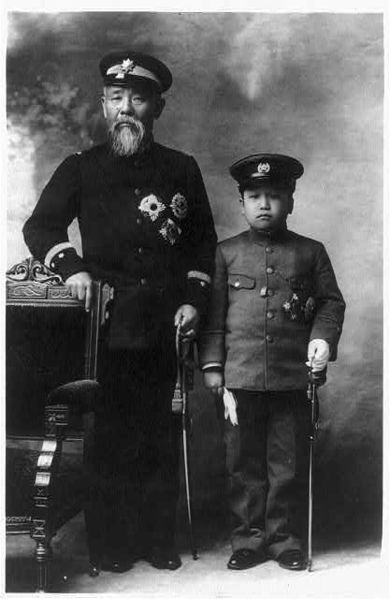

Masayoshi had many children (at least 13 sons and 11 daughters) and grandchildren. It is said that Emperor Meiji asked him how many children he had; but Masayoshi was unable to give an exact answer.

Masayoshi's son, Matsukata Kōjirō (1865 – 1950), invested his significant personal fortune in the acquisition of several thousand examples of Western painting, sculpture and decorative arts. His intention was that the collection should serve as the nucleus of a national museum of western art. Although not achieved during his lifetime, the 1959 creation of the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo was a vindication of this passion for art and a demonstration of the foresight which benefits his countrymen and others.

His granddaughter, journalist Haru Matsukata Reischauer, married the American scholar of Japanese history, academic, statesman and United States Ambassador to Japan, Edwin Oldfather Reischauer.