<Back to Index>

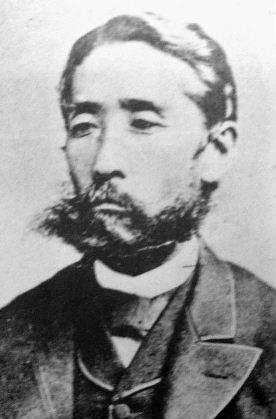

- Leader of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement Itagaki Taisuke, 1837

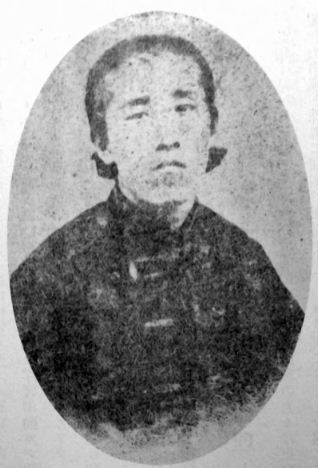

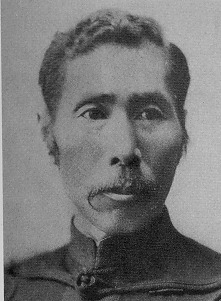

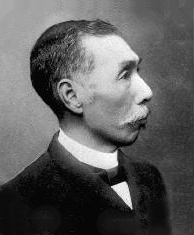

- 3rd Prime Minister of Japan Yamagata Aritomo, 1838

PAGE SPONSOR

Count Itagaki Taisuke (板垣 退助, 21 May 1837 – 16 July 1919) was a Japanese politician and leader of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement (自由民権運動 Jiyū Minken Undō), which evolved into Japan's first political party.

Itagaki Taisuke was born into a middle ranking samurai family in Tosa Domain, (present day Kōchi Prefecture). After studies in Kōchi and in Edo, he was appointed as sobayonin (councilor) to Tosa daimyo Yamauchi Toyoshige, and was in charge of accounts and military matters at the domain's Edo residence in 1861. He disagreed with the domain’s official policy of kōbu gattai (reconciliation between the Imperial Court and the Tokugawa shogunate), and in 1867 - 1868, he met with Saigō Takamori of the Satsuma Domain, and agreed to pledge Tosa's forces in the effort to overthrow the Shogun in the upcoming Meiji Restoration. During the Boshin War, he emerged as the leading political figure from Tosa domain, and claimed a place in the new Meiji government after the Tokugawa defeat.

Itagaki was appointed a Councilor of State in 1869, and was involved in several key reforms, such as the abolition of the han system in 1871. As a sangi (councilor), he ran the government temporarily during the absence of the Iwakura Mission.

However, Itagaki resigned from the Meiji government in 1873 over disagreement with the government's policy of restraint toward Korea (Seikanron) and, more generally, in opposition to the Chōshū - Satsuma domination of the new government.

In 1874, together with Gotō Shōjirō of Tosa and Etō Shimpei and Soejima Taneomi of Hizen, he formed the Aikoku Kōtō (Public Party of Patriots), declaring, "We, the thirty millions of people in Japan are all equally endowed with certain definite rights, among which are those of enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring and possessing property, and obtaining a livelihood and pursuing happiness. These rights are by Nature bestowed upon all men, and, therefore, cannot be taken away by the power of any man." This anti - government stance appealed to the discontented remnants of the samurai class and the rural aristocracy (who resented centralized taxation) and peasants (who were discontented with high prices and low wages). Itagaki's involvement in liberalism lent it political legitimacy in Japan, and he became a leader of the push for democratic reform.

Itagaki and his associations created a variety of

organizations to fuse samurai ethos with western

liberalism and to agitate for a national assembly, written

constitution and limits to arbitrary exercise of power by

the government. These included the Risshisha (Self

- Help Movement) and the Aikokusha (Society of

Patriots) in 1875. After funding issues led to initial

stagnation, the Aikokusha was revived in 1878 and

agitated with increasing success as part of the Freedom

and People's Rights Movement. The Movement drew the ire of

the government and its supporters. In 1882, Itagaki was

almost assassinated by a right wing militant, to whom he

allegedly said, "Itagaki may die, but liberty never!"

Government leaders met at the Osaka Conference of 1875, enticing Itagaki to return as a sangi (councilor): however, he resigned after a couple of months to oppose what he viewed as excessive concentration of power in the Genrōin.

Itagaki created the Liberal Party (Jiyuto) together with Numa Morikazu in 1881, which, along with the Rikken Kaishintō, led the nationwide popular discontent of 1880 - 1884. During this period, a rift developed in the movement between the lower class members and the aristocratic leadership of the party. Itagaki became embroiled in controversy when he took a trip to Europe believed by many to have been funded by the government. The trip turned out to have been provided by the Mitsui Company, but suspicions that Itagaki was being won over to the government side persisted. Consequently, radical splinter groups proliferated, undermining the unity of the party and the Movement. Itagaki was offered the title of Count (Hakushaku) in 1884, as the new peerage system known as kazoku was formed, but he accepted only on the condition that the title not be passed on to his heirs.

The Liberal Party dissolved itself on 20 October 1884. It was reestablished shortly before the opening of the Imperial Diet in 1890 as the Rikken Jiyūtō.

In April 1896, Itagaki joined the second Ito administration as Home Minister. In 1898, Itagaki joined with Ōkuma Shigenobu of the Shimpotō to form the Kenseitō, and Japan's first party government. Ōkuma became Prime Minister, and Itagaki continued serving as Home Minister. The Cabinet collapsed after four months of squabbling between the factions, demonstrating the immaturity of parliamentary democracy at the time in Japan.

Itagaki retired from public life in 1900 and spent the

rest of his days writing. He died of natural causes in

1919.

Itagaki is credited as being the first Japanese party leader and an important force for liberalism in Meiji Japan. He was elevated to the peerage posthumously, and given the rank of hakushaku (count).

His portrait has appeared on the 50 sen and 100 yen banknotes issued by the Bank of Japan.

Field Marshal Prince Yamagata Aritomo, OM (山縣 有朋, 14 June 1838 – 1 February 1922), also known as Yamagata Kyōsuke, was a field marshal in the Imperial Japanese Army and twice Prime Minister of Japan. He is considered one of the architects of the military and political foundations of early modern Japan. Yamagata Aritomo can be seen as the father of Japanese militarism. His support for many autocratic and aggressive policies directly undermined the development of an open society, and contributed to the coming of the Second World War.

Yamagata was born in a lower ranked samurai family from Hagi, the capital of the feudal domain of Chōshū (present day Yamaguchi prefecture). He went to Shokasonjuku, a private school run by Yoshida Shōin, where he devoted his energies to the growing underground movement to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate. He was a commander in the Kiheitai, a paramilitary organization created on semi - western lines by the Chōshū domain. During the Boshin War, the revolution of 1867 and 1868 often called the Meiji Restoration, he was a staff officer.

After the defeat of the Tokugawa, Yamagata together with

Saigō Tsugumichi was selected by the leaders of the new

government to go to Europe in 1869 to research European

military systems. Yamagata like many Japanese was strongly

influenced by the recent striking success of Prussia in

transforming itself from an agricultural state to a

leading modern industrial and military power. He accepted

Prussian political ideas, which favored military expansion

abroad and authoritarian government at home. On returning

he was asked to organize a national army for Japan, and he

became War Minister in 1873. Yamagata energetically

modernized the fledgling Imperial Japanese Army, and

modeled it after the Prussian army. He began a system of

military conscription in 1873.

As War Minister, Yamagata pushed through the foundation of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff, which was the main source of Yamagata's political power and that of other military officers through the end of World War I. He was Commander of the General Staff in 1874 – 76, 1878 – 82, and 1884 – 85.

Yamagata in 1877 led the newly modernized Imperial Army against the Satsuma Rebellion led by his former comrade in revolution, Saigō Takamori of Satsuma. At the end of the war, when Saigo's severed head was brought to Yamagata, he ordered it washed, and held the head in his arms as he pronounced a meditation on the fallen hero.

He also prompted Emperor Meiji to write the Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors, in 1882. This document was considered the moral core of the Japanese army and naval forces until their dissolution in 1945.

Yamagata was awarded the rank of field marshal in 1898. He showed his leadership on military issues as acting War Minister and Commanding General during the First Sino - Japanese War; as the Commanding General of the Japanese First Army during the Russo - Japanese War; and as the Chief of the General Staff Office in Tokyo.

He is considered political and military ideological

ancestor of the Hokushin-ron

as he traced the first lines of a national defensive

strategy against Russia

after Russo - Japanese War.

Yamagata was one of the group of seven political leaders, later called the genrō, who came to dominate the government of Japan. The word can be translated principal elders or senior statesmen. The genrō were a subset of the revolutionary leaders who shared common objectives and who by about 1880 had forced out or isolated the other original leaders. These seven men (plus two who were chosen later after some of the first seven had died) led Japan for many years, through its great transformation from an agricultural country into a modern military and industrial state. All the genrō served at various times as cabinet ministers, and most were at times prime minister. As a body, the genrō had no official status, they were simply trusted advisers to the Emperor. Yet the genrō made collectively the most important decisions, such as peace and war and foreign policy, and when a cabinet resigned they chose the new prime minister. In the twentieth century their power diminished because of deaths and quarrels among themselves, and the growing political power of the army and navy. But the genrō clung to the power of naming prime ministers up to the death of the last genrō Prince Saionji in 1940.

Yamagata and Itō Hirobumi were long the most prominent of the seven, and after the assassination of Itō in 1909, Yamagata dominated the genrō. But Yamagata also held a large and devoted power base in the officers of the army and the militarists. He became the towering leader of Japanese conservatives. He profoundly distrusted all democratic institutions, and he devoted the later part of his life to building and defending the power, especially the political power, of the army.

During his long and versatile career, Yamagata held numerous important governmental posts. In 1882, he became president of the Board of Legislation (Sanjiin) and as Home Minister (1883 – 1887) he worked vigorously to suppress political parties and repress agitation in the labor and agrarian movements. He also organized a system of local administration, based on a prefecture - county - city structure which is still in use in Japan today. In 1883 Yamagata was appointed to the post of Lord Chancellor, the highest bureaucratic position in the government system before the Meiji Constitution of 1889.

Yamagata became the third Prime Minister of Japan after the opening of the Imperial Diet under the Meiji Constitution from 24 December 1889 to 6 May 1891. During his first term, the Imperial Rescript on Education was issued.

Yamagata became Prime Minister for a second term from 8 November 1898 to 19 October 1900. In 1900, while in his second term as Prime Minister, he ruled that only an active military officer could serve as War Minister or Navy Minister, a rule that gave the military control over the formation of any future cabinet. He also enacted laws preventing political party members from holding any key posts in the bureaucracy.

He was President of the Privy Council from 1893 – 1894 and 1905 – 1922.

Attending the coronation of the Russian Czar Nicholas II on November 1, 1894, Yamagata made a tentative offer to Spain on buying the Philippines for 40 million pounds.

In 1896, Yamagata led a diplomatic mission to Moscow, which produced the Yamagata – Lobanov Agreement confirming Japanese and Russian rights in Korea.

Yamagata was elevated to the peerage, and received the title of koshaku (prince) under the kazoku system in 1907.

From 1900 to 1909, Yamagata opposed Itō Hirobumi, leader of the civilian party, and exercised influence through his protégé, Katsura Tarō. After the death of Itō Hirobumi in 1909, Yamagata became the most influential politician in Japan and remained so until his death in 1922, although he retired from active participation in politics after the Russo - Japanese War. However, as president of the Privy Council from 1909 to 1922, Yamagata remained the power behind the government and dictated the selection of future Prime Ministers until his death.

In 1912 Yamagata set the precedent that the army could dismiss a cabinet. A dispute with prime minister Marquis Saionji Kinmochi over the military budget became a constitutional crisis, known as the Taisho Crisis after the newly enthroned Emperor. The army minister, General Uehara Yūsaku, resigned when the cabinet would not grant him the budget he wanted. Saionji sought to replace him. Japanese law required that the ministers of the army and navy must be high ranking generals and admirals on active duty (not retired). In this instance all the eligible generals at Yamagata's instigation refused to serve in the Saionji cabinet, and the cabinet was compelled to resign.

Yamagata was a talented garden designer, and today the gardens he designed are considered masterpieces of Japanese gardens. A noted example is the garden of the villa Murin-an in Kyoto.

In 1906, Yamagata received the Order of Merit by King Edward VII. Thereafter, he received the Knight Grand Cross of St Michael and St George. His Japanese decorations included the Order of the Golden Kite (1st class), Order of the Rising Sun (1st class with Paulownia Blossoms, Grand Cordon) and the Collar and Grand Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum.