<Back to Index>

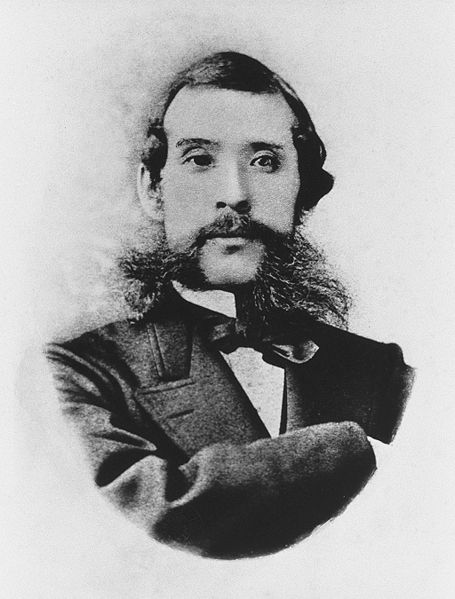

- Minister of Education Mori Arinori, 1847

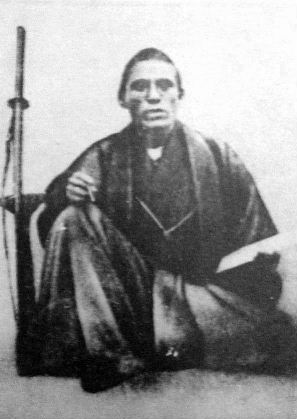

- Home and Finance Minister Ōkubo Toshimichi, 1830

PAGE SPONSOR

Viscount Mori Arinori (森 有礼, August 23, 1847 – February 12, 1889) was a Meiji period Japanese statesman, diplomat and founder of Japan's modern educational system.

Mori was born in the Satsuma domain (modern Kagoshima prefecture) from a samurai family, and educated in the Kaisenjo School for Western Learning run by the Satsuma domain. In 1865, he was sent as a student to University College London in Great Britain, where he studied western techniques in mathematics, physics and naval surveying. He returned to Japan just after the start of the Meiji Restoration and took on a number of governmental positions within the new Meiji government.

He was the first Japanese ambassador to the United States, from 1871 - 1873. During his stay in the United States, he became very interested in western methods of education and western social institutions. On his return to Japan, he organized the Meirokusha, Japan’s first modern intellectual society.

Mori was a member of the Meiji Enlightenment movement, and advocated freedom of religion, secular education, equal rights for women (except for voting), international law, and (most drastically) the abandonment of the Japanese language in favor of English.

In 1875, he established the Shoho Koshujo (Japan's first commercial college), the predecessor of Hitotsubashi University. Thereafter, he successively served as ambassador to Qing Dynasty China, Senior Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs, ambassador to Great Britain, member of Sanjiin (legislative advisory council) and Education Ministry official.

He was recruited by Itō Hirobumi to join the first cabinet as Minister of Education and continued in the same post under the Kuroda administration from 1886 to 1889. During this period, he enacted the "Mori Reforms" of Japan's education system, which included six years of compulsory, co-educational schooling, and the creation of high schools for training of a select elite. Under his leadership, the central ministry took greater control over school curriculum and emphasized Neo - Confucian morality and national loyalty in the lower schools while allowing some intellectual freedom in higher education.

He has been denounced by post - World War II liberals as a reactionary who was responsible for the Japanese elitist and statist educational system, while he was equally condemned by his contemporaries as a radical who imposed unwanted westernization on Japanese society at the expense of Japanese culture and tradition, for example. He advocated the use of English. He was also a known Christian.

Mori was stabbed by an ultra - nationalist on the very day of promulgation of the Meiji Constitution in 1889, and died the next day. The assassin was outraged by Mori's alleged failure to follow religious protocol during his visit to Ise Shrine two years earlier; for example, Mori was said to have not removed his shoes before entering and pushed aside a sacred veil with a walking stick.

Selected portions of his writings may be found in W.R. Braisted's book Meiroku Zasshi: Journal of the Japanese Enlightenment.

Ōkubo Toshimichi (大久保 利通, September 26, 1830 – May 14, 1878), was a Japanese statesman, a samurai of Satsuma, and one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration. He is regarded as one of the main founders of modern Japan.

Ōkubo was born in Kagoshima, Satsuma Province, (present day Kagoshima Prefecture) to Ōkubo Juemon a low ranking retainer of Satsuma daimyō Shimazu Nariakira. He was the eldest of five children. He studied at the same local school with Saigō Takamori, who was three years older. In 1846, he was given the position of aide to the domain's archivist.

Shimazu Nariakira recognized Ōkubo's talents and appointed him to the position of tax administrator in 1858. When Nariakira died, Ōkubo joined the plot to overthrow the Tokugawa Shogunate. Unlike most Satsuma leaders, he favored the position of tōbaku (倒幕, overthrowing the Shogunate), as opposed to kōbu gattai (公武合体, marital unity of the Imperial and Tokugawa families) and hanbaku (opposition to the Shogunate) over the Sonnō jōi movement.

The Anglo - Satsuma War of 1863, along with the Richardson Affair and the September 1863 coup d'état in Kyoto convinced Ōkubo that the tobaku movement was doomed. In 1866, he met with Saigō Takamori and Chōshū Domain's Kido Takayoshi to form the secret Satcho Alliance to overthrow the Tokugawa.

On January 3, 1868, the forces of Satsuma and Chōshū seized the Kyoto Imperial Palace and proclaimed the Meiji Restoration. The triumvirate of Ōkubo, Saigō and Kido formed a provisional government. Appointed to be Home Lord, Ōkubo had a huge amount of power through his control of all local government appointments and the police force. Initially the new government had to rely on funds from the Tokugawa lands (which the Meiji government seized in toto). He then was able to appoint all new leaders for this land, most of the people he appointed as governors were young men, some were his friends, like Matsukata Masayoshi, and others were the rare Japanese who had gained some education in Europe or America. Okubo used the power of the Home Ministry to promote industrial development building roads, bridges, and ports, all things which the Tokugawa Shogunate had refused to do.

As Finance Minister in 1871, Ōkubo enacted a Land Tax Reform, the Haitōrei Edict, which prohibited samurai from wearing swords in public, and ended official discrimination against the outcasts. In foreign relations, he worked to secure revision of the unequal treaties and joined the Iwakura Mission on its around - the - world trip of 1871 to 1873.

Realizing that Japan was not in any position to challenge the western powers in its new present state, Ōkubo returned to Japan on September 13, 1873 just in time to take a strong stand against the proposed invasion of Korea (Seikanron). He also participated in the Osaka Conference of 1875 in an attempt to bring about a reconciliation with the other members of the Meiji oligarchy.

However, he was unable to win over former colleague Saigō Takamori regarding the future direction of Japan. Saigo became convinced that Japan's new policy of modernization was wrong and in the Satsuma Rebellion

of 1877, some Satsuma rebels under the leadership of Saigō fought

against the new government's army. As Home Minister Ōkubo took command

of the army and fought against his old friend Saigo. With the defeat of

the rebellion's forces, Ōkubo was considered a traitor by many of the

Satsuma samurai. On May 14, 1878, Okubo was assassinated by Shimada Ichirō and six Kanazawa Domain samurai while on his way to the imperial palace, only a few minutes walk from the Sakurada gate where Ii Naosuke had been assassinated 18 years earlier.

Ōkubo was one of the most influential leaders of the Meiji Restoration and the establishment of modern governmental structures. Albeit briefly, for a time he was the most powerful man in Japan. A devout loyalist and nationalist, he enjoyed the respect of his colleagues and enemies alike.

Tarō Asō, the 92nd Prime Minister of Japan, is a great - great - grandson of Ōkubo Toshimichi. Ōkubo's second son, Makino Nobuaki, served as Foreign Minister.

In the manga / anime series Rurouni Kenshin, Ōkubo Toshimichi appears to seek Himura Kenshin's assistance in destroying the threat posed by the revolt of Shishio Makoto. Kenshin is uncertain, and Ōkubo gives him a May 14 deadline to make his decision. On his way to seek Kenshin's answer on that day, he is supposedly assassinated by Seta Sōjirō, Shishio's right hand man, and the Ichirō clan desecrates his corpse and claim they killed him. (Watsuki makes a comparison to President of the United States Abraham Lincoln with Ōkubo in his notes.)

In Boris Akunin's novel, The Diamond Chariot, Erast Fandorin investigates the plot to assassinate Ōkubo, but fails to prevent the assassination.