<Back to Index>

- Philologist and Physician Girolamo Mercuriale, 1530

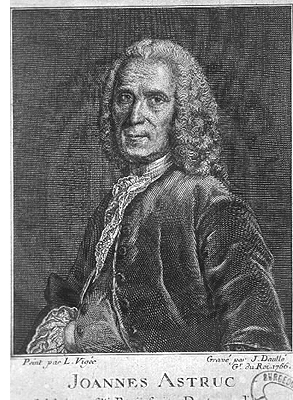

- Physician Jean Astruc, 1684

PAGE SPONSOR

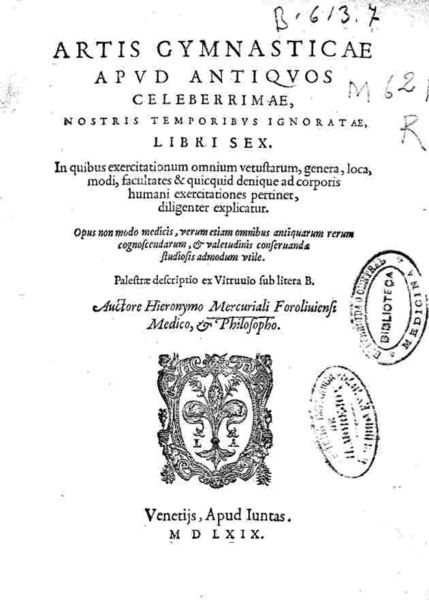

Girolamo Mercuriale (also known as Geronimo Mercuriali or by his Latin name Hieronymus Mercurialis) (September 30, 1530 – November 13, 1606) was an Italian philologist and physician, most famous for his work De Arte Gymnastica.

Born in the city of Forlì, the son of Giovanni Mercuriali, also a doctor, he was educated at Bologna and Padua and Venice, where he received his doctorate in 1555. Settling in his natal city, he was sent on a political mission to Rome. The pope at the time was Paul IV.

In Rome, he made favorable contacts and had free access to the great libraries, where with sweeping enthusiasm, he studied the classical and medical literature of the Greeks and Romans. His studies of the attitudes of the ancients toward diet, exercise and hygiene and the use of natural methods for the cure of disease culminated in the publication of his De Arte Gymnastica (Venice, 1569). With its explanations concerning the principles of physical therapy, it is considered the first book on sports medicine. The illustrations which accompanied the second edition of the work (1573) proved incredibly fertile to the Western imagination regarding the nature of athletics in the Classical world. Modern scholarship has recognized that these illustrations were largely speculative creations of Mercuriale and his collaborators. (It was not however the first Renaissance book about the benefits of exercise; Cristobal Méndez's Libro del Exercicio (1553), which was rediscovered in 1930, predates it by 16 years.)

The book De Arte Gymnastica gave Mercuriale fame. He was called to occupy the chair of practical medicine in Padua in 1569. During this time, he translated the works of Hippocrates, and, armed with this knowledge, wrote De morbis cutaneis (1572), considered the first scientific tract on skin diseases; De morbis mulieribus ("On the diseases of women") (1582); De morbis puerorum ("On the diseases of children") (1583); De oculorum et aurium affectibus; and "Censura e dispositio operum Hippocratis" (Venice, 1583). In De morbis puerorum, Mercuriali observed contemporary trends in child rearing. He wrote that women generally finished breastfeeding an infant exclusively after the third month and entirely after around thirteen months.

In 1573, he was called to Vienna to treat the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II. The emperor, pleased with the treatment he received (although he was to die three years later), made him an imperial count palatine.

He returned home in the following years; in 1575, the Venetian Senate awarded him a six year contract as a professor at the University of Padua. Although he was largely hailed as a hero of the city, his reputation would take a sharp turn downwards after his inept handling of the outbreak of plague in Venice in 1576 - 1577. Mercuriale was summoned by the Venetian government to head a team of medical professionals who would advise about the disease. Arguing against the quarantining and use of lazarettos by the Board of Health, Mercuriale maintained that the disease infecting Venice could not possibly be plague. He and another medical professor, Girolamo Capodivacca, offered to personally treat the sick in Venice on the condition that the quarantines and other precautions put in place by the Board of Health be lifted. The professors and their assistants traveled freely between infected and safe houses, administering treatment, to the horror of the Board of Health and officials in Padua and surrounding cities, who worried the disease would spread. When Mercuriali and Capodivacca began their treatment of the sick in Venice, the death toll had come to a near halt — this was one of the reasons they believed it could not be the true plague. However, by the end of June, the month when they began their work, it rose at an incredible rate. By the beginning of July, the Senate ordered Mercuriale and Capodivacca to be quarantined themselves and it was largely believed that their questionable methods were at fault for the spread of the plague, which eventually claimed 50,000 Venetians.

However, Mercuriale salvaged his own reputation in the following years with the 1577 publication of De Pestilentia, his treatise about the plague, which had been delivered as a series of lectures at the University of Padua.

Mercuriale was a prolific writer, though many books were ascribed to him that were compiled from the works of others. He remained in Padua until 1587, when he began teaching at the University of Bologna. In 1593, he was called by Cosimo de' Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, to Pisa. Cosimo wanted to increase the prestige of the university there and offered a record salary of 1,800 gold crowns, to become 2,000 gold crowns after the second year.

Mercuriale returned to Forlì in 1606 and died there few months later.

Among his many disciples was the Swiss botanist Gaspard Bauhin.

On 11 March 2009, the Olympic Museum in Lausanne hosted a

colloquium given by the Faculty of Medicine of the

University of Geneva commemorating the 400th anniversary

of the death of Girolamo Mercuriale.

Jean Astruc (Sauves, Auvergne, March 19, 1684 – Paris, May 5, 1766) was a professor of medicine at Montpellier and Paris, who wrote the first great treatise on syphilis and venereal diseases, and also, with a small anonymously published book, played a fundamental part in the origins of critical textual analysis of works of scripture. Astruc was the first to try to demonstrate — using the techniques of textual analysis that were commonplace in studying the secular classics — the theory that Genesis was composed based on several sources or manuscript traditions, an approach that is called the documentary hypothesis.

The son of a Protestant minister who had converted to Catholicism (although the House of Astruc was of medieval Jewish origin), Astruc was educated at Montpellier, one of the great schools of medicine in early modern Europe. His dissertation and first publication, submitted when he was only 19, is on decomposition, and contains many references to recent research on the lungs by Thomas Willis and Robert Boyle. After teaching medicine at Montpellier he became a member of the medical faculty at the University of Paris. His numerous medical writings, or materials for the history of medical education at Montpellier, are now forgotten, but the work published by him anonymously in 1753 has secured for him a permanent reputation. This book, brought out anonymously in 1753, was entitled Conjectures sur les mémoires originauz don't il paroit que Moyse s'est servi pour composer le livre de la Génèse. Avec des remarques qui appuient ou qui éclaircissent ces conjectures ("Conjectures on the original documents that Moses appears to have used in composing the Book of Genesis. With remarks that support or throw light upon these conjectures"). The title cautiously gives the place of publication as Brussels, safely beyond the reach of French authorities. Not all the 18th century books that declare that they were printed at Amsterdam or Geneva, to cite two other familiar imprints, were actually printed outside France. It was a safeguard.

Indeed a safeguard was required. The forcible "re-Catholicization" of Astruc's Languedoc homeland in the frame of the Counter - Reformation, when the Protestant "Camisards" were being deported or sent to the galleys, was a very recent memory. In Astruc's own times the writers of the Encyclopédie were working under great pressure and in secret, for Catholic Church did not offer a tolerant atmosphere for biblical criticism. This was somewhat ironic, for Astruc saw himself as fundamentally a supporter of orthodoxy; his unorthodoxy lay not in denying Mosaic authorship of Genesis, but in his defense of it. In the previous century scholars such as Thomas Hobbes and Baruch Spinoza had drawn up long lists of inconsistencies and contradictions and anachronisms in the Torah, and used these to argue that Moses could not have been the author of the entire five books. Astruc was outraged by this "sickness of the last century", and determined to use modern 18th century scholarship to refute that of the 17th. Using methods already well established in the study of the Classics for sifting and assessing differing manuscripts, he drew up parallel columns and assigned verses to each of them according to what he had noted as the defining features of the text of Genesis: whether a verse used the term "YHWH" (Yahweh) or the term "Elohim" (God) referring to God, and whether it had a doublet (another telling of the same incident, as for example the two accounts of the creation of man, and the two accounts of Sarah being taken by a foreign king). Astruc found four documents in Genesis, which he arranged in four columns, declaring that this was how Moses had originally written his book, in the image of the four Gospels of the New Testament, and that a later writer had combined them into a single work, creating the repetitions and inconsistencies which Hobbes, Spinoza and others had noted.

Astruc's work was taken up by a succession of German scholars, the intellectual climate in Germany then being more conducive to scholarly freedom, and in their hands formed the foundation of modern critical exegisis of the Old and New Testaments.